Nikhil Chopra: My name is Nikhil Chopra. I live in Goa on the west coast of India in tropical lushness, in the quietude of nature. And I surround myself with friends and family and community. So these things are very important to me. My process, as I brought up the word community, is very connected to people. It really, at the end of the day, is about conversations and dialogues that I would like to generate around me. I think of myself as an artist who enjoys putting in that cauldron various aspects of my talent and makeup, drawing and painting, being really at the backbone of what I do, and that's how I've been trained, but also trying to find a language that is kind of unique to what I do. I bring in performance and elements of the theatre into my practice as well. So it's a sort of mash-up of drawing, painting, performance, art and theatre.

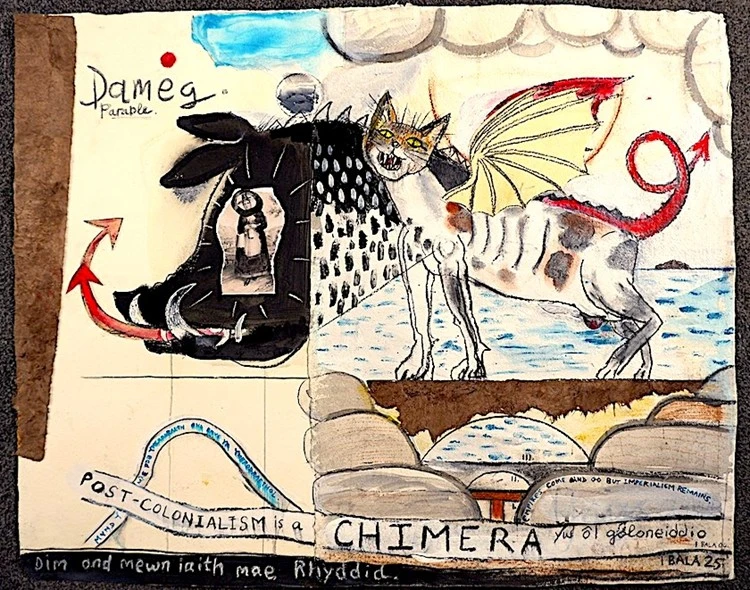

So I kind of like to think of myself as someone who sits in the spaces between, let's say, drawing and painting, between performance and theatre. And my identity and my makeup and my history and my manner in a way is essentially scrutinized through the act of making. I do think of my past from a very critical place. I do think of myself as a colonized body, and the act of performing and making art is really a way for me to dismantle and question in a way of these various presets, whether they're about being a man, whether they're about being Indian, whether they're about being urbanized, whether they're about being international. These questions really do become a very important part of that narrative that I like to play with, and that's what I'm bringing here to Swansea as well.

Andrea Powell, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery: How did you approach this project?

Nikhil Chopra: Well, this project approached me and as opposed to me approaching the project, it came to me from Zehra Jumabhoy, who's a curator that I've been working with and been in contact with for many, many years. We started our careers in some sense together all the way back in the early 2000s when we were in Bombay. But essentially, I think of my work, I think of the way in which I make things as reactive, as opposed to active. It's really the conditions in a sense are created for me. And then I kind of place in a sense what I do in a very shape-shifting sense, in a very site-specific way within the context of, let's say a place, a building.

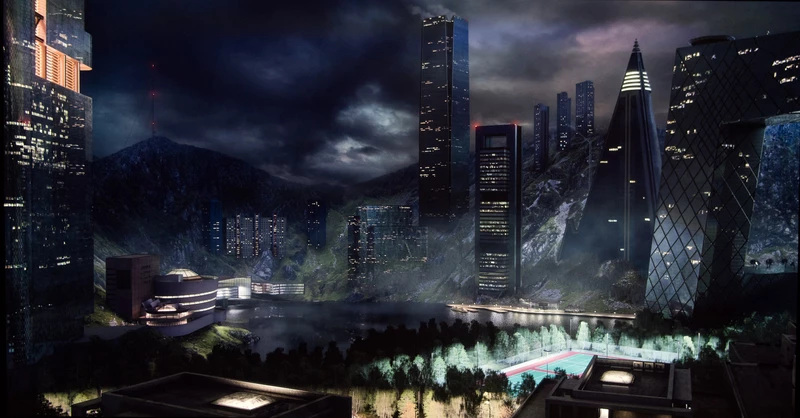

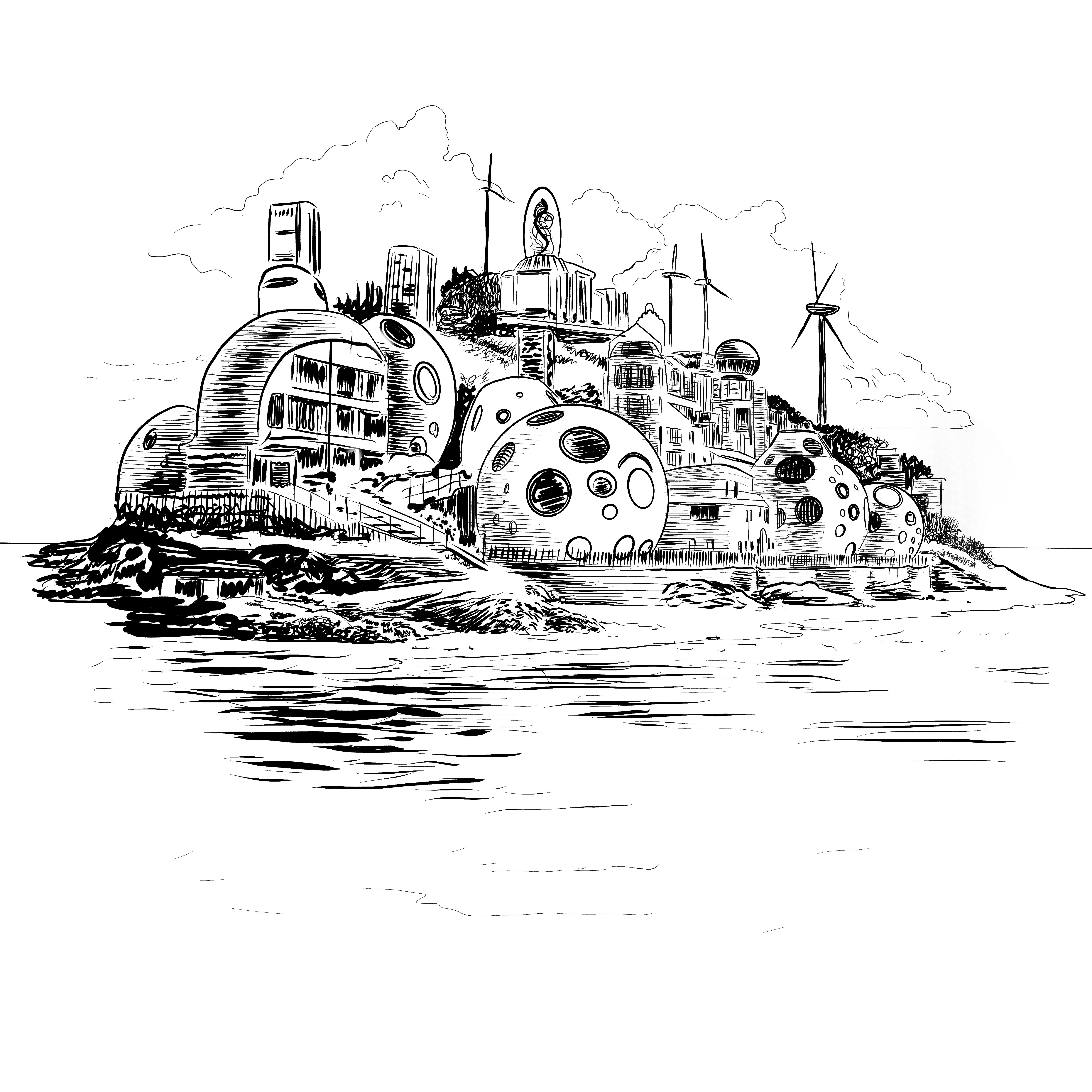

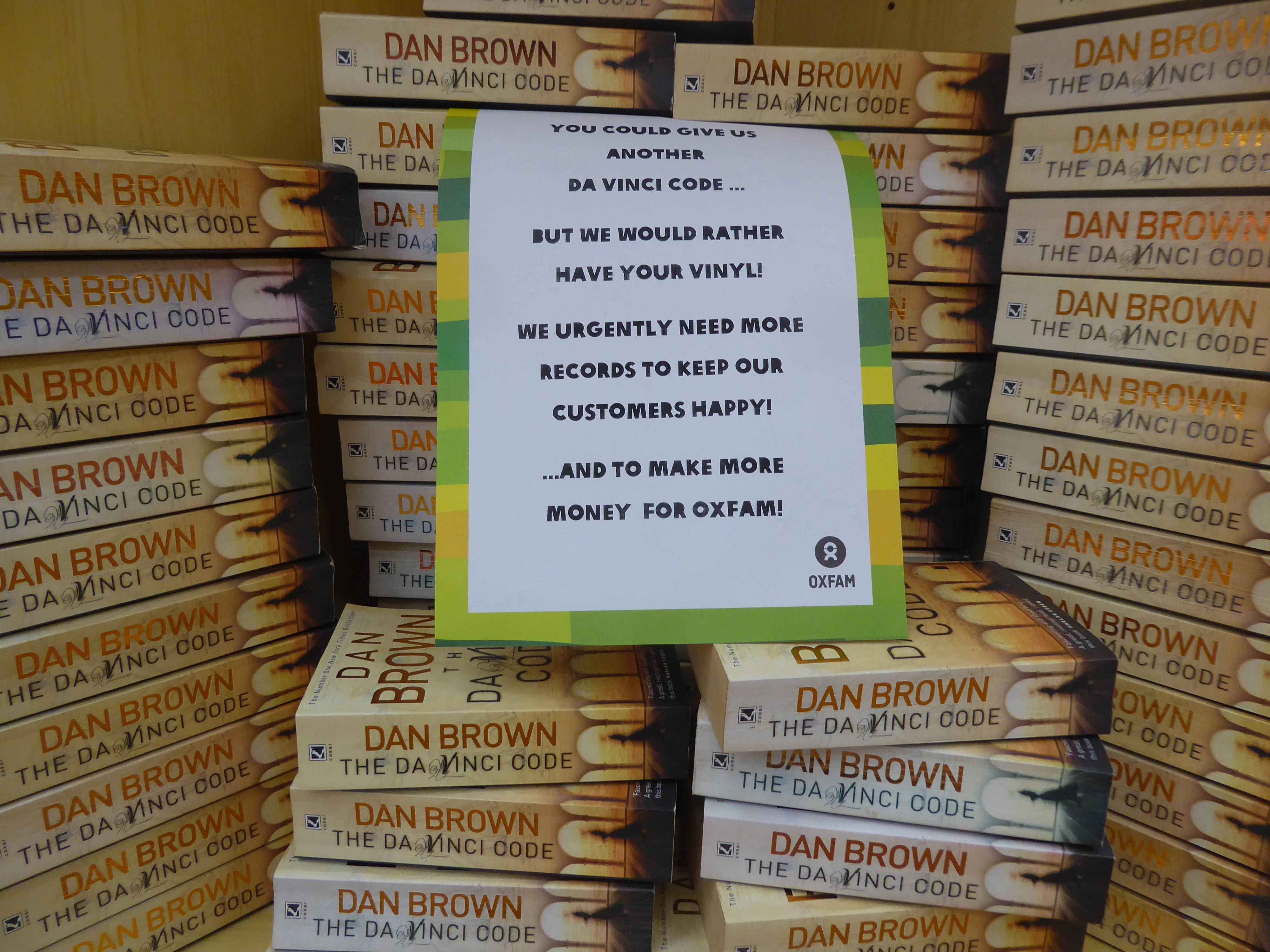

And so I was very immediately very attracted to and excited about coming to a place that was off-centre. I'm really interested in, as much as I'm interested in the big cities like London and Paris and New York and Bombay and Delhi, I'm really interested on what happens on the fringes of these megacities. It's in a sense, cultures that feed into large-scale urban cultures. So I'm really interested in looking at how, in a sense these other centres or these other nodes in a sense survive work and sustain themselves both culturally, economically, and how do they maintain in a sense their identity. And in that sense, Wales becomes a very interesting case in point, and that's been very much the driving force of my ideas for this project.

Andrea Powell, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery: Tell me a bit about the research themes and subjects that fed into the Celf Commission and what steps you've taken to develop your ideas.

Nikhil Chopra: In these contexts, I think, as I've said, my work is always wanting to react to a set of conditions. It was very important for me to do a site visit. And in a sense, I had the privilege of doing two. And a site visit really is about being present in the place and allowing ideas to come to me and come to the project. I'm a great lover of nature and landscape, and not just from the place of looking at it with rose-tinted glasses and a sense of romance, but a sense of criticality as well. So Zehra and her partner, Alex, were very kind to drive me through the countryside and take me through, let's say what was idealized as the Welsh landscape. I visited not just the building at Glynn Vivian and saw the gallery spaces that I had access to and the collections, which are incredible.

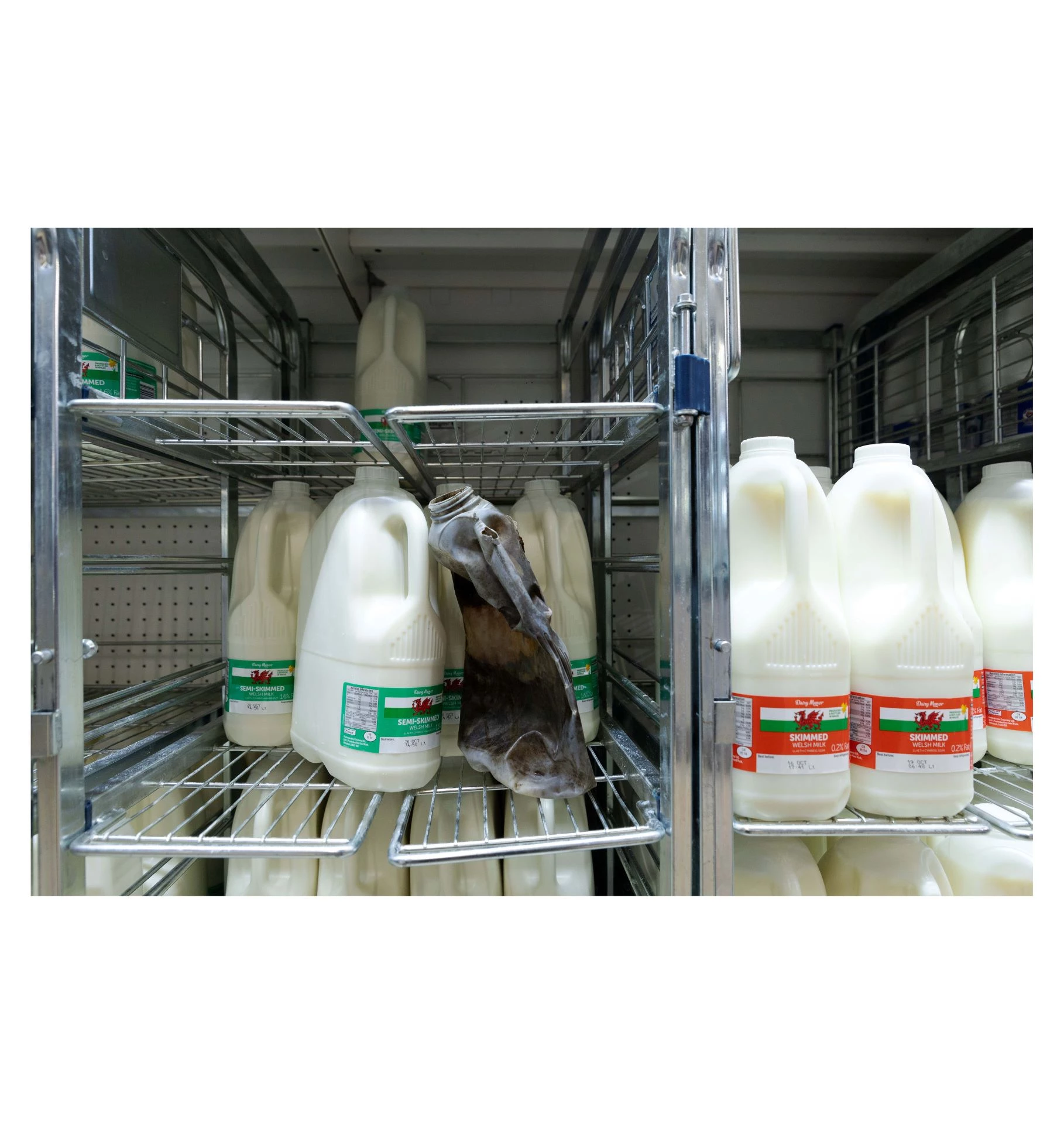

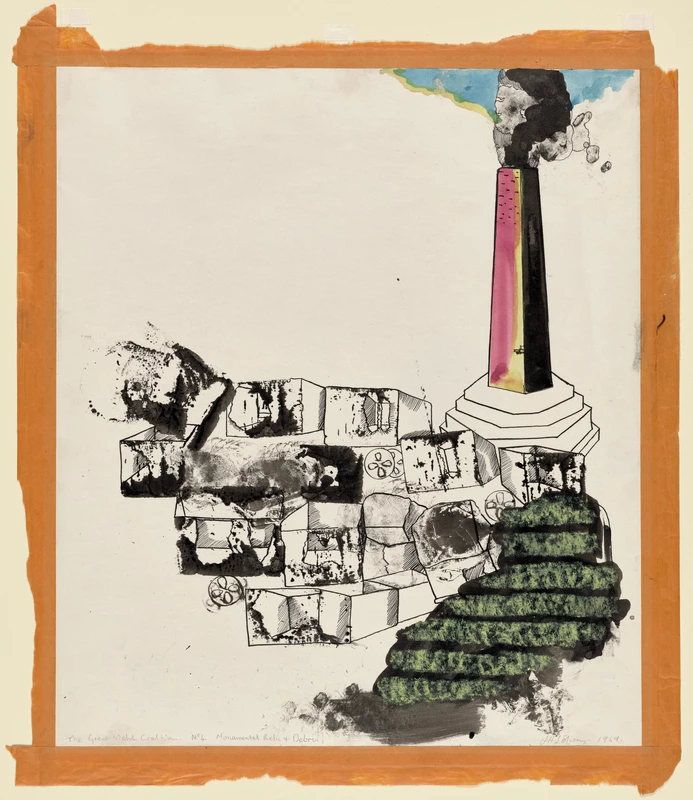

But I was also very quickly drawn to the large steel factory. And I was interested in the irony that that building has and that industry and that massive factory has, which is, that is owned today by Tata. And Tata is really an Indian company that bought over Fort Talbot Steelworks, which was also British Steel at one point. And in a way it was a symbol of reversing the idea of colonialism. It's the colonized now become the owners in a sense of something that was really very much a part and an identity of this place. Not with a sense of making profit, but just the sense of ownership. I think that was really interesting to me. And in my second visit I was able to, and you were able to actually organise a visit for me into the steel factory, and I was really able to take a look at the nuts and bolts of how this factory worked, not just its history, but the way and the conditions that were prevalent today.

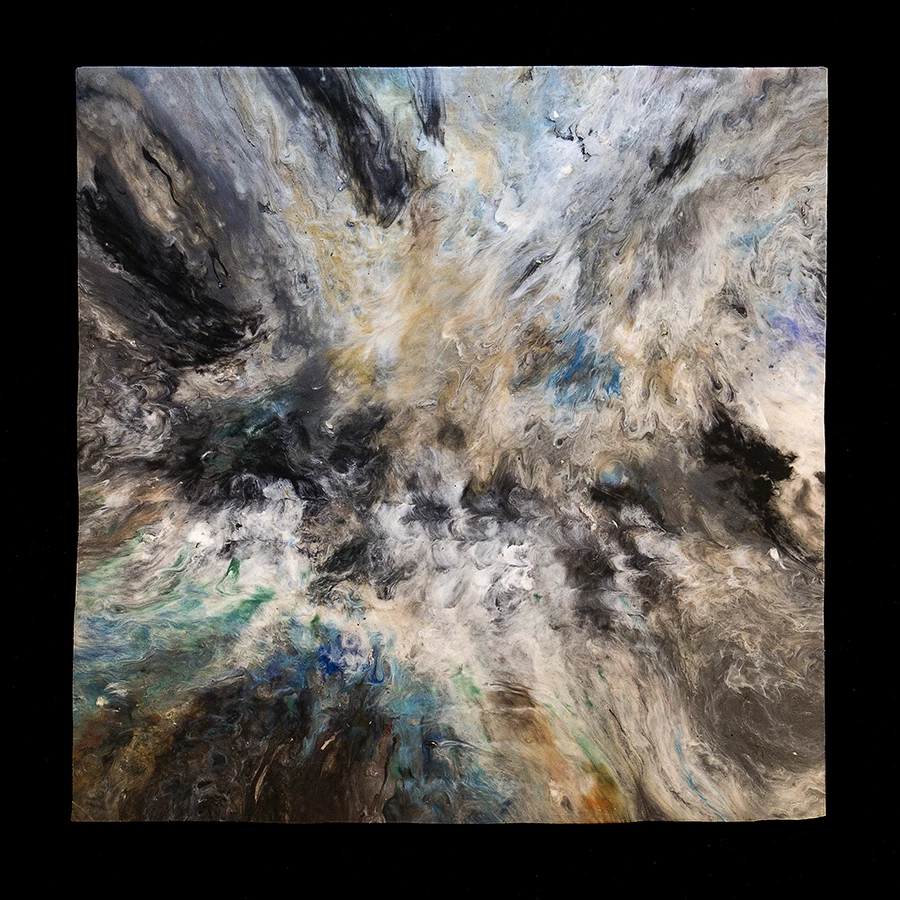

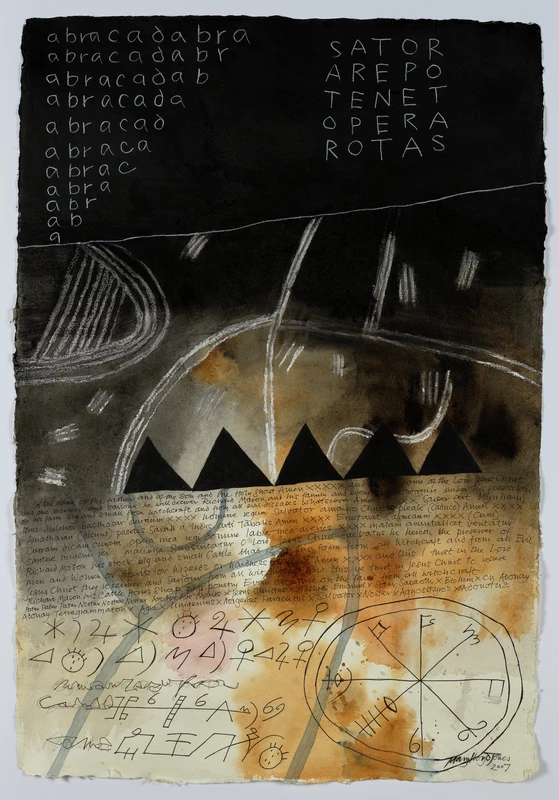

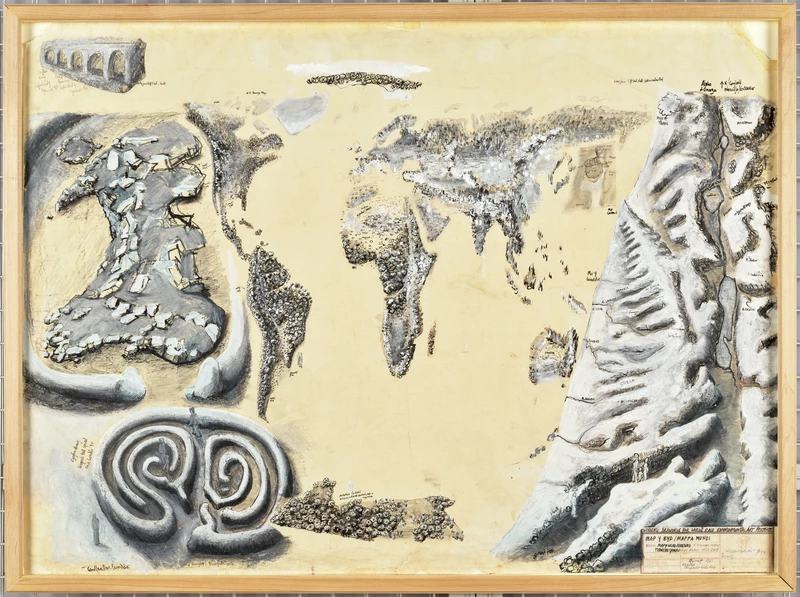

And what was very apparent to me was the sickness in a sense of the Industrial Revolution that is felt here in a sense that this was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. This was the birthplace and the Industrial Revolution is what drives the colonial engine. And to me, that was a really good little clue into what it is that I would want to take on. And over the past years, I've been very interested in landscapes and distress. I'm not really interested in landscapes from a place of romance as much as I'm interested in how troubled the ecology is and how troubled in a sense, not just the ecology, but also, and our relationship to landscape, is really about mapmaking and drawing lines and borders and boundaries. And a lot of the work that I've been doing is about blurring those boundaries and erasing some of those boundaries and looking at a tree for a tree and not on whose land that tree sits on.

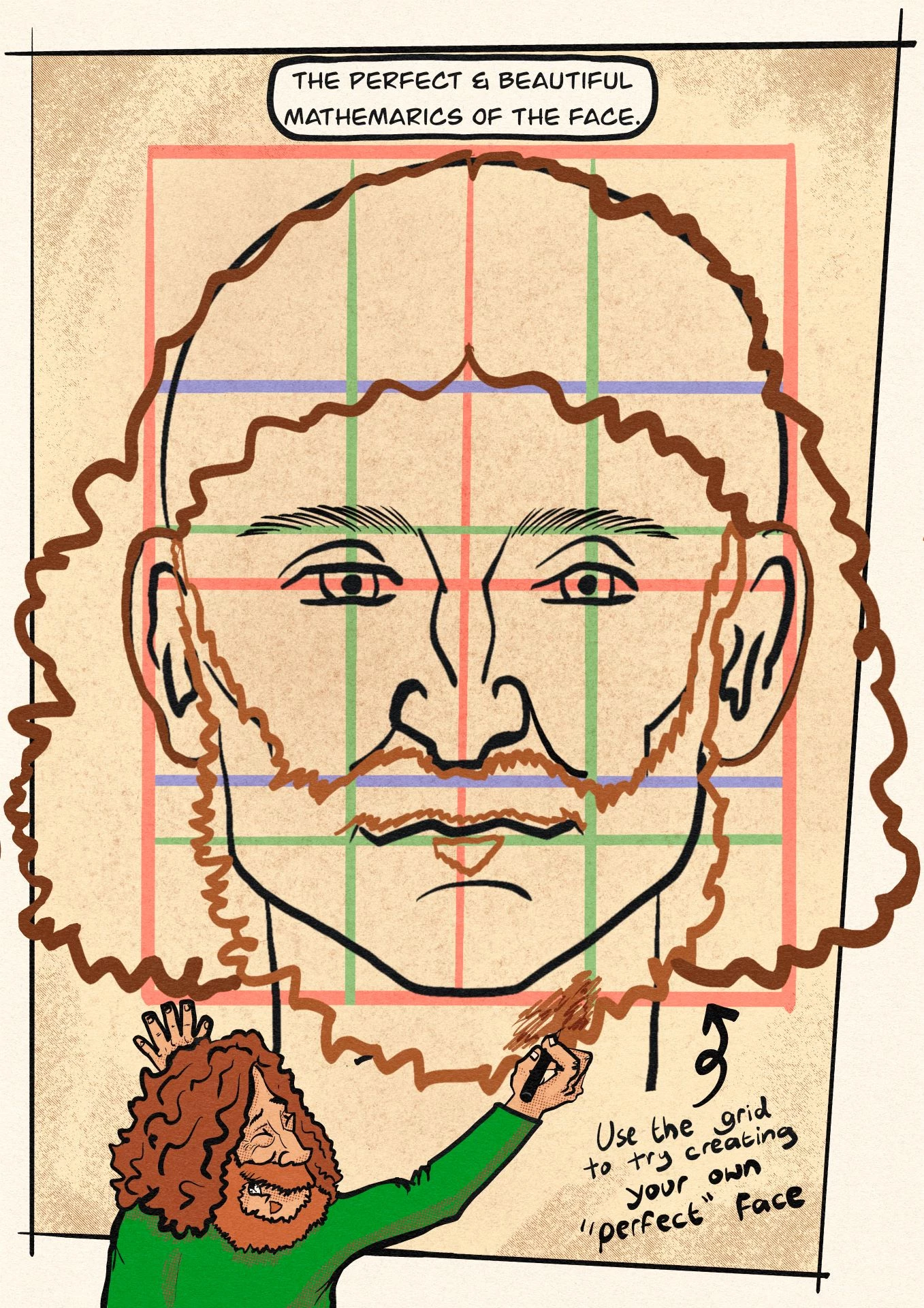

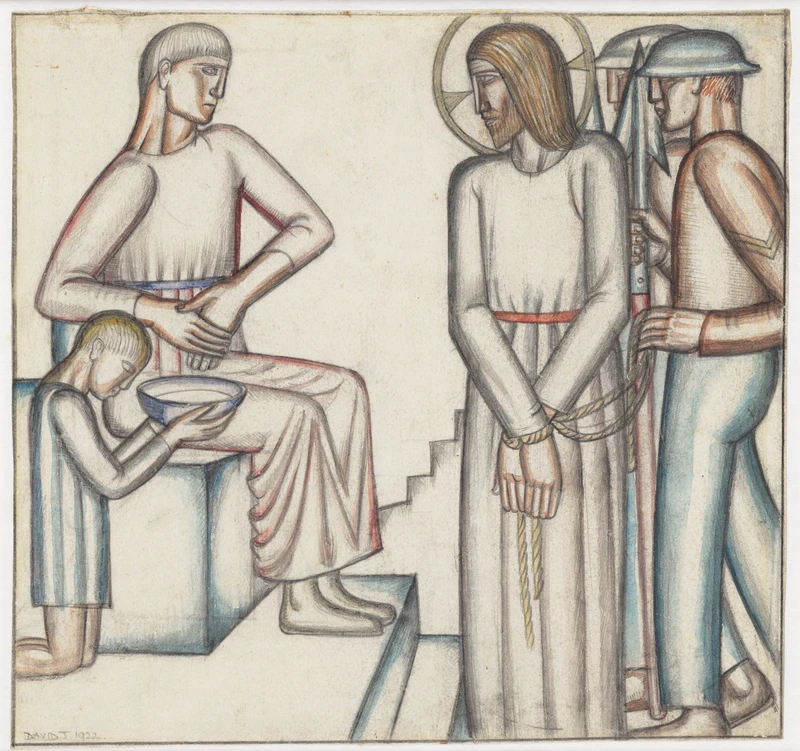

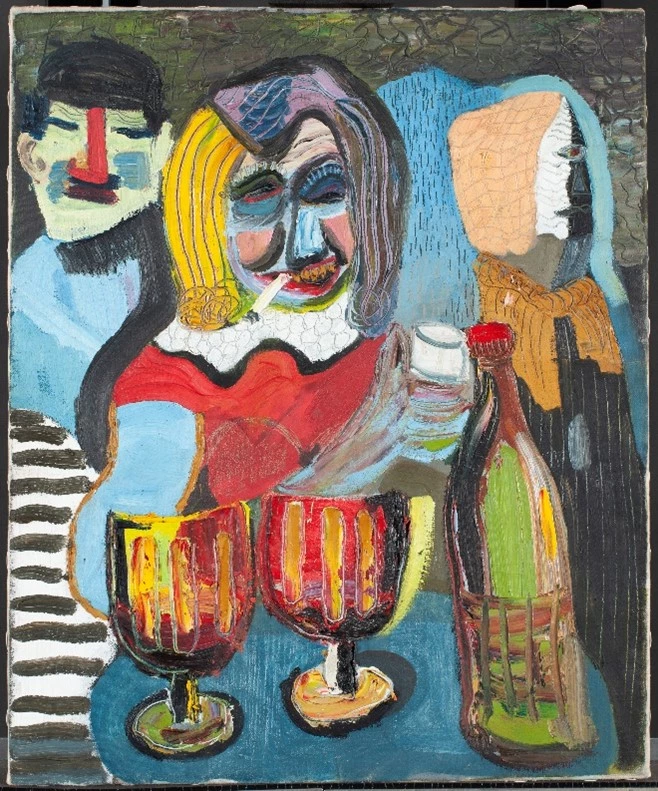

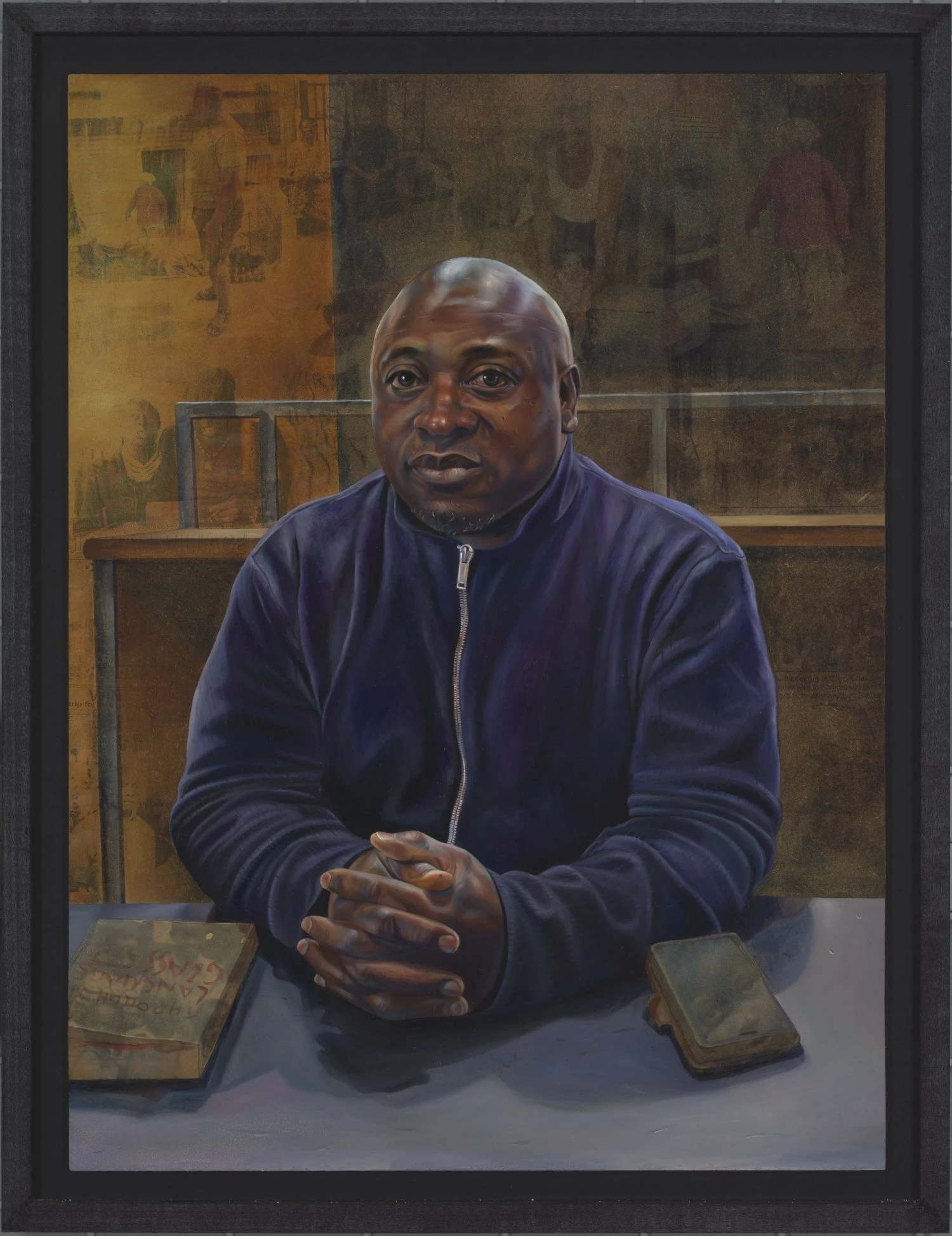

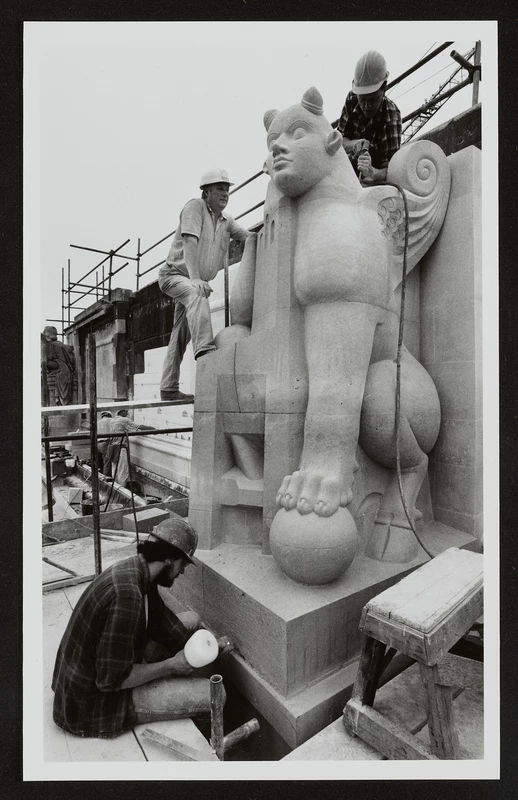

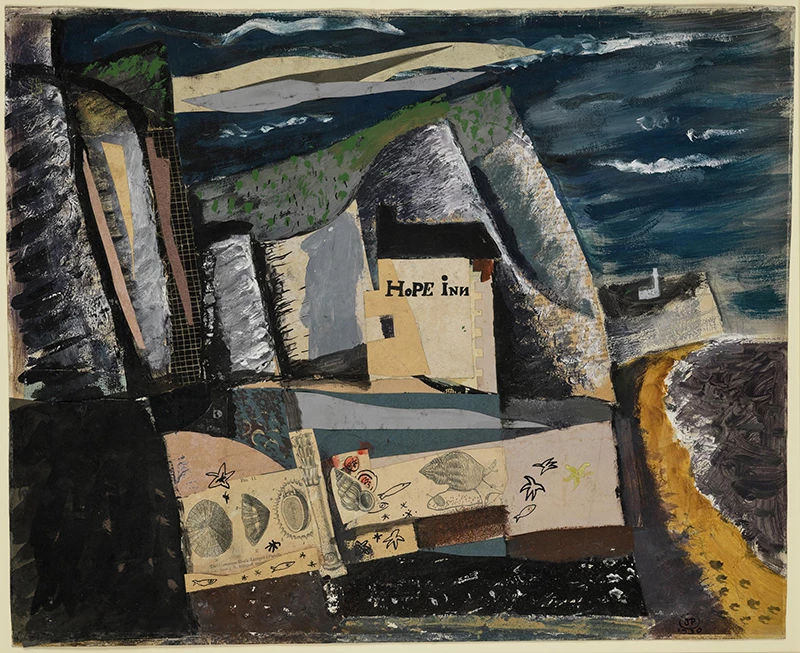

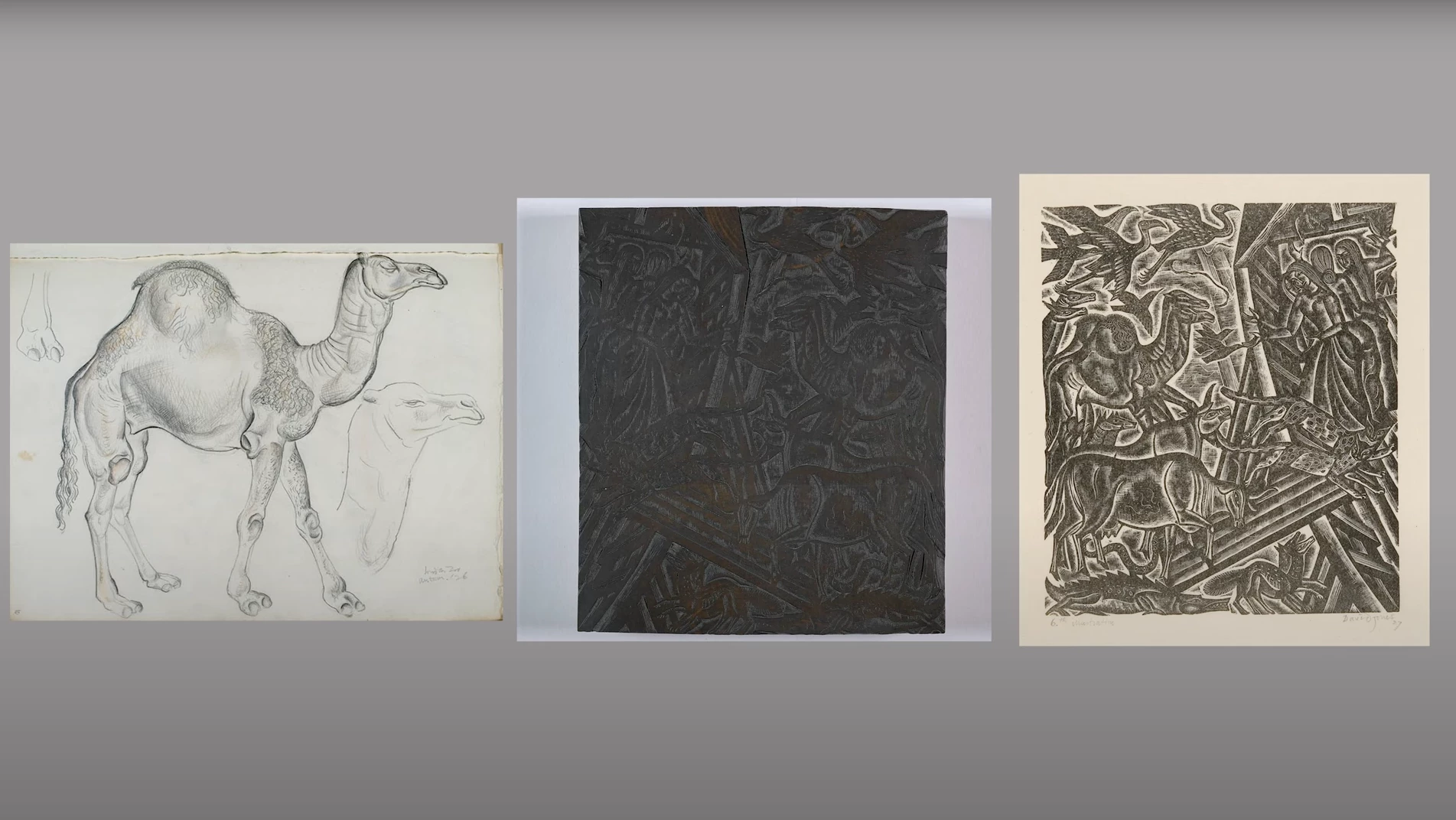

And also then to look at the factory as a factory and not whose factory it is, but just the fact that it sits there like a canker sore in the middle of pristine nature. So it's really bringing that sensibility into... And that's really been what's informed my composition of this performance. Well, that's on one side. And on the other side, I have really enjoyed looking at the history of this building, the Glynn Vivian Gallery and the persona of Glynn Vivian, and really enjoyed looking at it with a bit of tongue-in-cheek. And I kind of enjoy how Glynn Vivian was this flaneur, was this dandy who travelled the world extensively with his sketchbook and recorded and also collected, but collected and did these acts, if you will, which seemed to be quite performative to an extent, was to not just fit in, but to his position as a British citizen.

And Wales really is. If we were to look at the history of this place, I mean, I can look at it from a place of saying Wales was probably one of the first colonies of the British Empire. And what it does is, I mean, these powers in a sense put us in a position where we need to aspire to become subjects of that empire. And so I see Glynn Vivian's life process as a means for him to get validation for his existence and his nobility. And in a way, there are slippages in that space because he doesn't quite make it. There's a clumsiness in the way in which he goes about it, which I'm really excited and interested in because there is a place where we need to look at aspiration as the back end of what hegemonic power does. It makes us into things that they want us to see us as opposed to how we choose to create ourselves and what light we want to create ourselves in.

So the script was in a sense, handed to Glynn Vivian, and he interprets it. And that interpretation is something that I find very interesting, especially in the collection, but also in the way in which he dressed up and he enjoyed kind of a theatricality to his life. That's really informed my research for this piece.

Andrea Powell, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery: How will this performance relate to your previous work and ways of working?

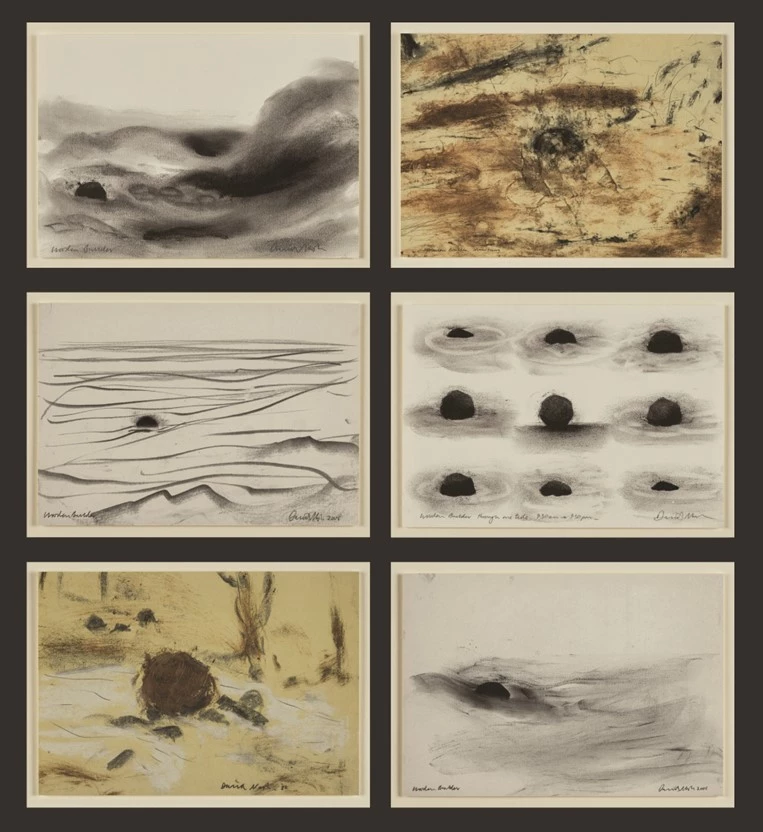

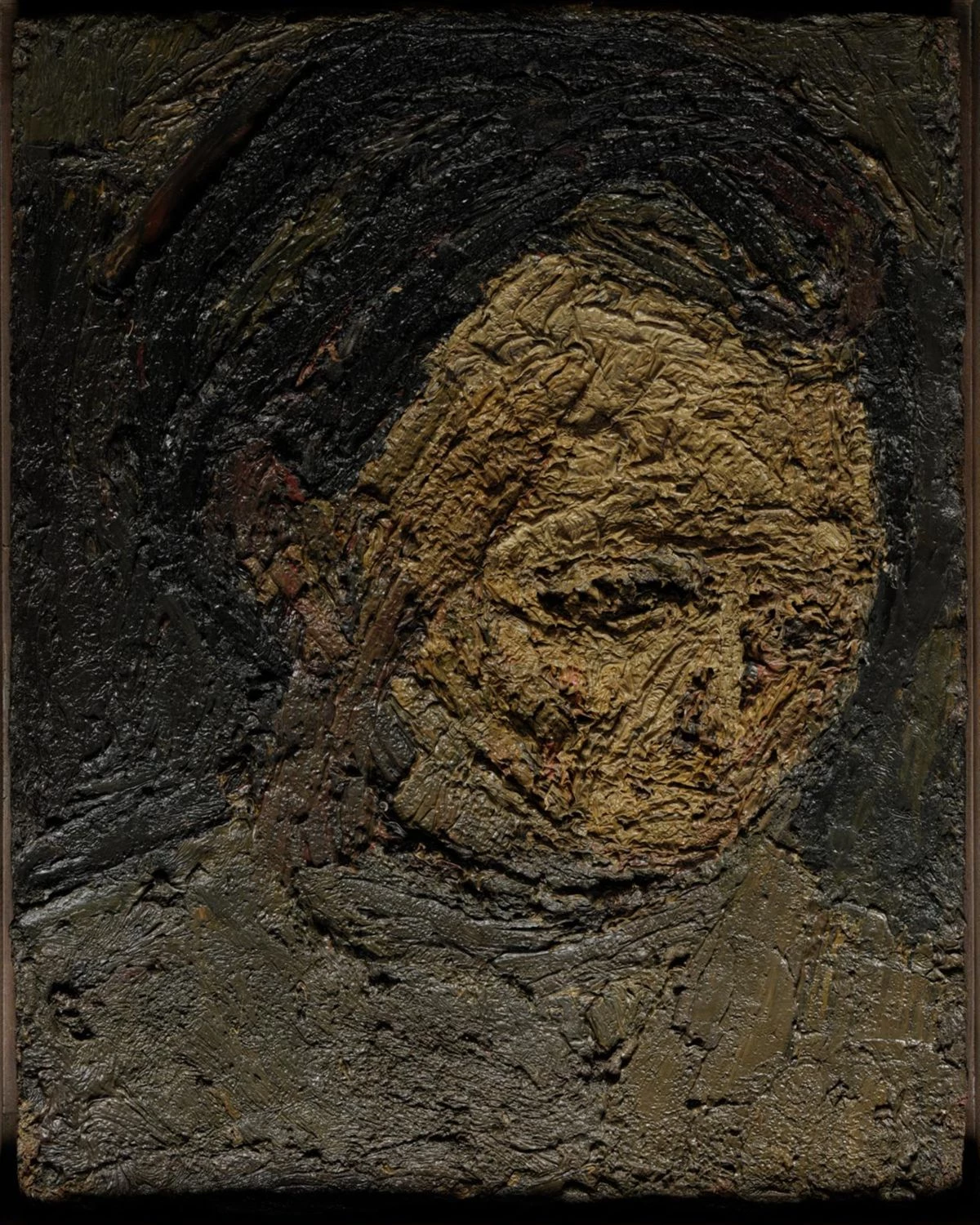

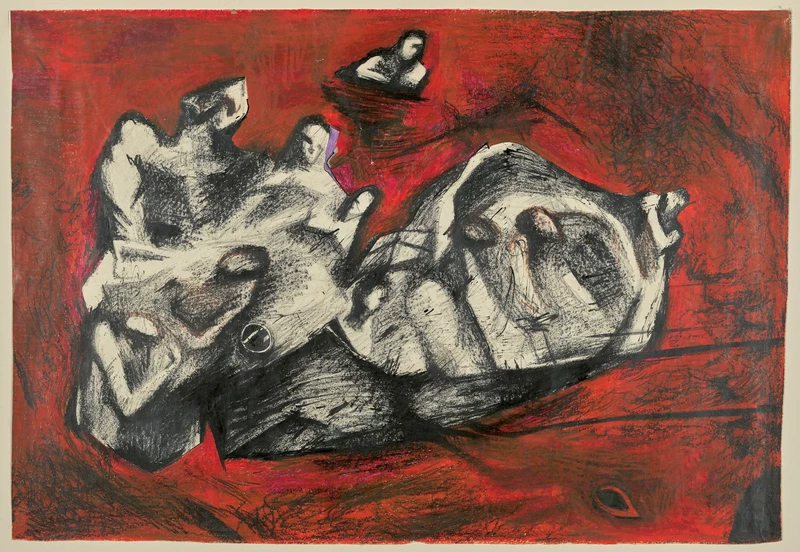

Nikhil Chopra: Well, there are a couple of ways of looking at what I'm doing. I mean, I look at what I'm doing in a couple of ways. One is to sort of look at it as one large body of work, of lifetime work. So this sort of feeds right and into the trajectory that I'm on right now where I put the drawing really at the centre of what I'm doing, and that really becomes the task that I give myself. And that's a very daunting task to look at a blank piece of canvas and to say, "Okay, how is this composition going to pan out?" And certain things enter the work, which is an element of trust and allow for doubt and mistakes and stumbles and falls to really become part of the mise-en-scène of the peace. But also to look at, as I mentioned, landscapes from a place of subjugation and subjecting land in a sense to the way in which we subject bodies and to kind of extend from the body into landscape and allow for the landscape to extend into the body.

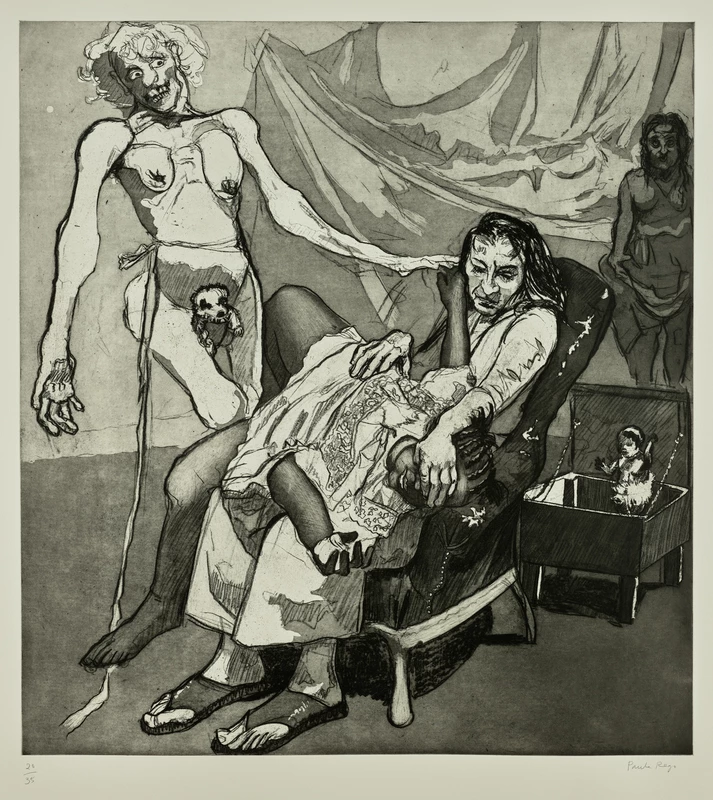

So largely what I'm doing over the past few years is in a way even blurring the lines between body and landscape and landscape as body, and then how do we understand ownership? In a way, the work began with me thinking about how colonizers came to the subcontinent and used image-making as a way to exercise ownership. So turn of the century, etchings and drawings were taken back to empire and brought back to empire, and were used as sort of trophy heads, if you will, like a tiger head saying, "Oh, look at what we own now."

So yeah. So I kind of used this idea of making drawings as a form of exercising my ownership. So I'd like to think about the fact that as I make this drawing of Wales, through this act, I become the owner in a sense of this landscape and of this place and of this moment. So it's really about exercising ownership and taking back that power from powers that had us feel powerless. This act of drawing really becomes an important tool to tip the scale and to balance that relationship with power that I'm most interested in. And that's, in a sense, been largely how I've been dealing with the performance work over the years.

Andrea Powell, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery: How would you like people to interact with the work? What would you like them to take away from the experience?

Nikhil Chopra: Well, I try not to assume the position of audiences or try to pre-empt their reactions and actions because that would be me making work for an audience. This is something that I try to stay away from doing. I kind of would like to think about this as a process for myself first. The idea is what is it that I am learning and unpacking through this process? And then the performance and then the act of making is very much happening in the now, is happening in the moment. And it's essentially a dialogue that gets set up in the moment. And what will happen in that moment is very difficult to pre-empt. So I don't impose, in a sense, a position that the audience needs to take. I don't suggest where they should stand. I don't suggest how they should behave. I don't suggest when they should enter, when they should exit.

I create those conditions for myself. And somehow, especially in the context of a gallery space like this, where audiences come to look at art, there is a manner in which that they take on right? There is a kind of rule of thumb that they take on. One of them is don't touch the artwork, which is something that I appreciate. And there is a context. I mean, audiences are already going to be coming with a sense of awareness that they're going to be interacting with an artwork. And that's my fourth wall essentially. And that's the kind of space that is in between the audience and me. But there is really no way for me to suggest what the audience should experience and what they should go away with because I'm interested in connecting with everyone, from children to seniors, to parents, to mothers, to fathers, to cleaners, to security guards, to interns, to students.

I'm really interested in a wide range of demographics, and I like to think that the work is really for everyone. I'm also not working in a very cryptic way. I'm not really interested in existing in a space place of abstraction. I give people very clear signifiers and very clear meanings that come out from making a landscape painting that are identifiable. I want people to relate to it. I want to connect with people to languages that they're already used to looking at, which is very simply making a picture and what that entails. So yeah, I'm interested in demystifying this process of making art and connecting with people right across the board.

Andrea Powell, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery: Is there anything else that you would like to share?

Nikhil Chopra: Well, what I guess is to invite audiences to come with an appetite and patience and a desire to not just stay, but to come back to experience a long-duration performance in its various moments. So it's a challenge. I like to challenge audiences to push themselves as much as I'm pushing myself. And I like to arouse a sense of curiosity in them to see how will this end, or how did it begin? And to use the now and the moment that they're experiencing as clues to piece their own narrative together to understand perhaps what may have happened and what could happen. And that's for me, the place I really want to put the audience in. If there is one position that I want an audience, or if it is one thing that I want audiences to experience is to be curious, inquisitive, and stay.