Edward Burne-Jones is bad for your health – or so they said. Some contemporaries saw in his work traces of sexual deviance, sickness, disease. An artist of the strange. ‘When people would explain Burne-Jones to me long ago,’ the French critic Octave Mirbeau wrote in 1896 ‘they would say: ‘Please note the hematoma around the eyes: it is unique in art. One cannot tell whether it is occasioned by self-abuse or lesbian practices, by natural love or tuberculosis.’1

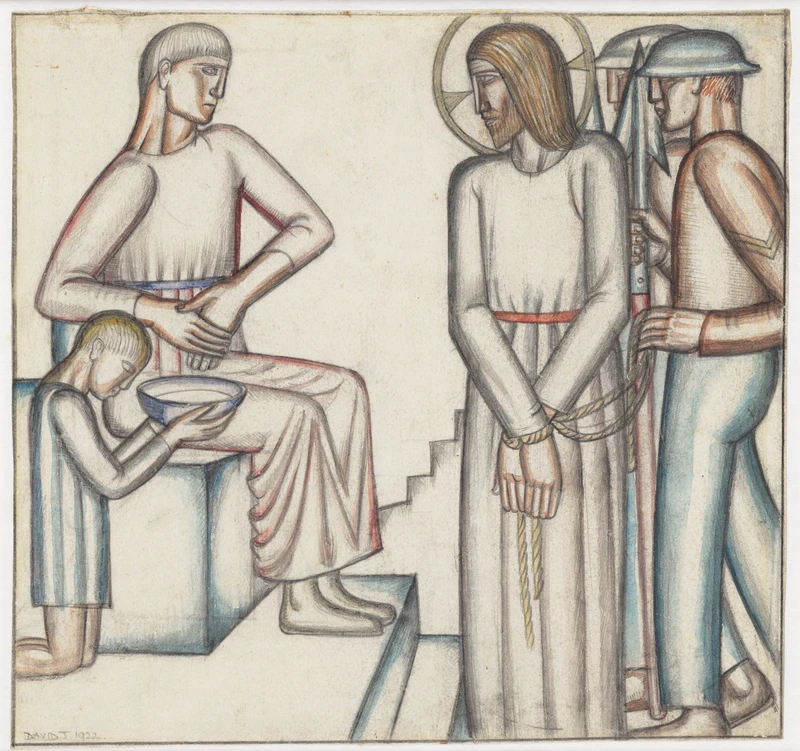

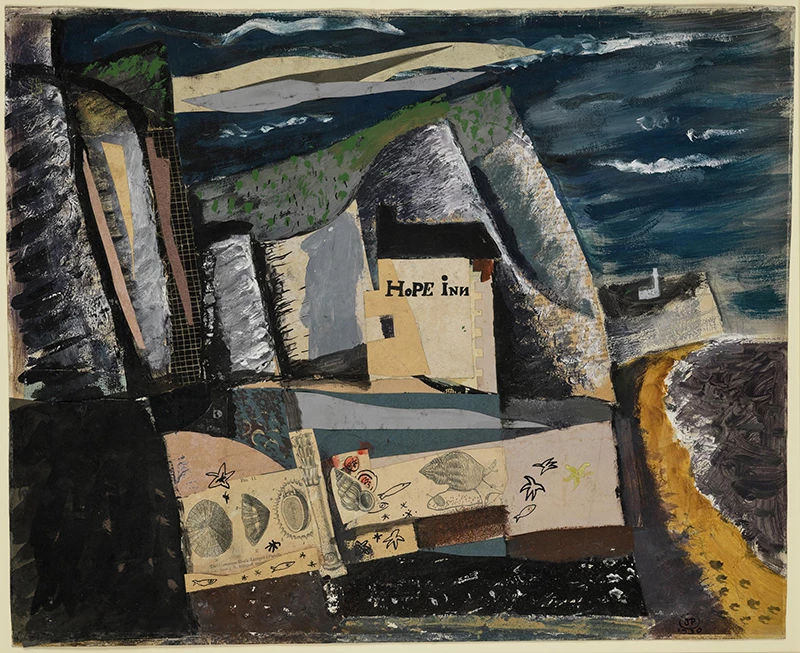

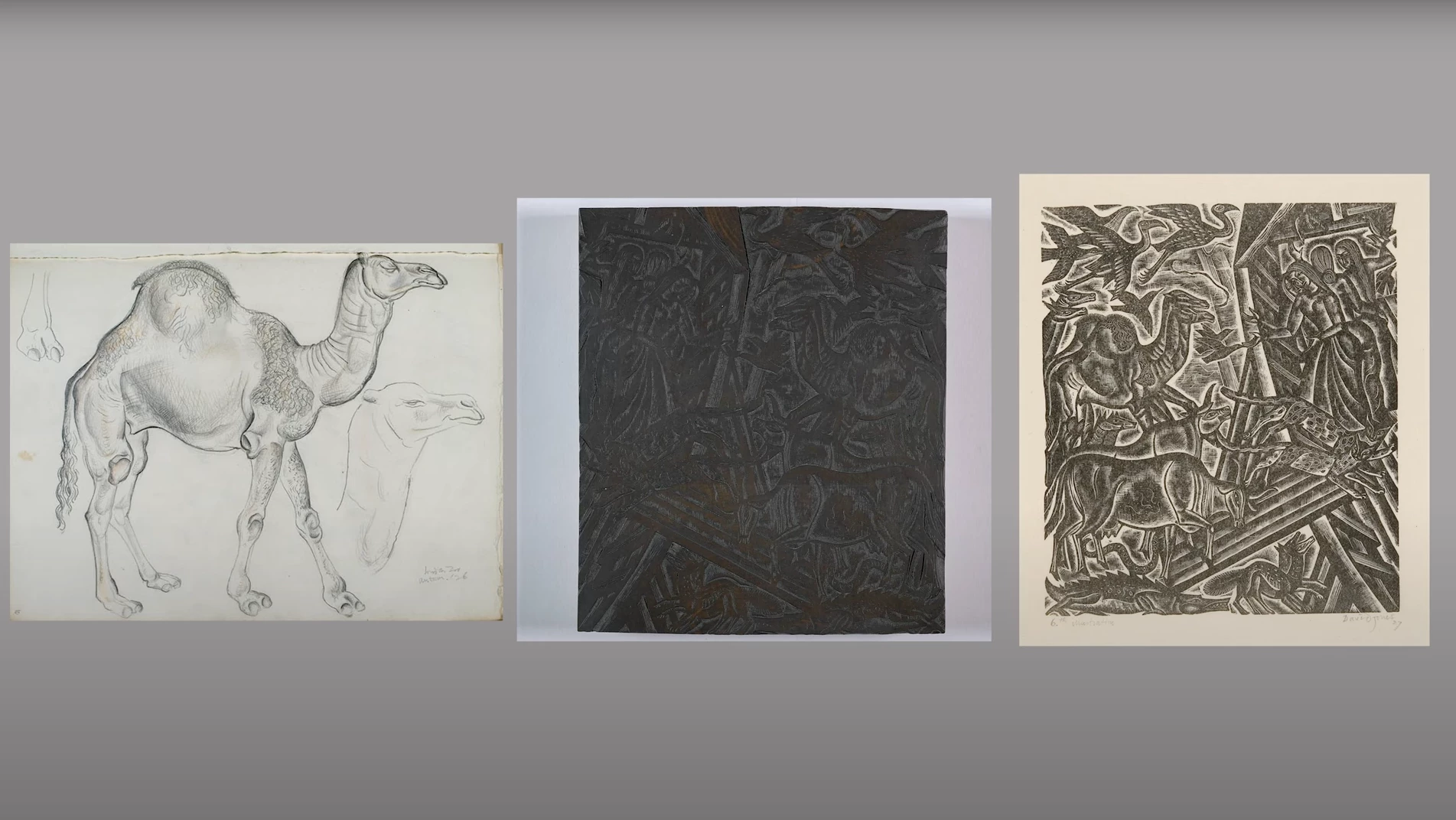

Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales holds a series of four photogravures - printed reproductions of Burne Jones’ Legend of Briar Rose paintings at Buscot Park, Oxfordshire – based on the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale. Four fairy tale moments, in velvety monochrome. These are liminal pieces – neither photograph nor etching, but something else, something strange, something in-between. Matte surfaces, dark shadows; soft-focused like the edges of sleep. Beautiful, but nightmarish too, and – like all good fairy tales – grim. Printed in 1892 by Thomas Agnew & Sons under Burne-Jones’s guidance, they were intended as keepsakes to meet public demand for reproductions of his popular Briar Rose paintings.

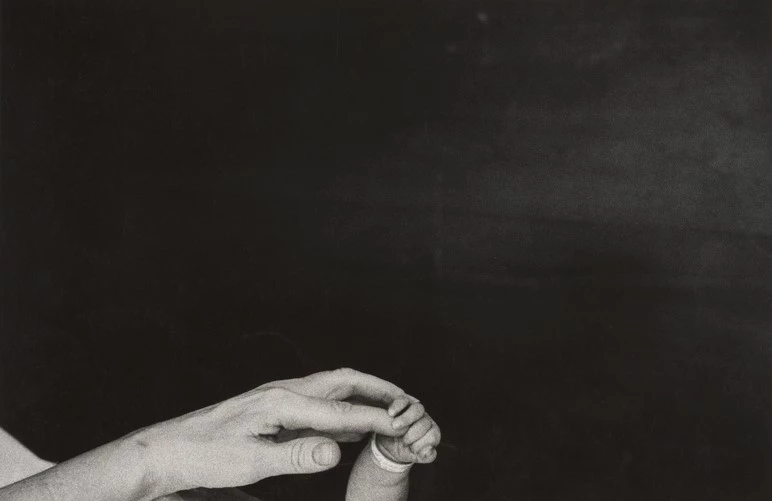

The images show a Prince stumbling across the bewitched Royal Castle, under its spell of 100 years’ sleep. The Castle is thick with rose briars grown wild and wayward over time. The bewitched beauty is in a deep, strange sleep; her body laid out as though on a mortuary slab but with her torso tilted up. Her arms are stiff at her side, face drooped towards us. Neither dead nor wholly alive, neither in this world nor quite out of it, she exists somewhere else, somewhere strange, somewhere in-between.

And so, this is how you find us. Asleep in the grey. Dreaming of an awakening, we wait.

Edward Burne-Jones is often described as a dreamer. Associated with the Aesthetic movement, with its famous motto ‘art for art’s sake’, some still see his works as mythical fantasies: magical other-worlds which offered respite from the realities of Victorian life. Today, many art historians are debunking that myth, showing how his work is deeply entwined with politics, social commentary and everyday human experience. In Interlacings (2008), Caroline Arscott argues for an embodied approach to his work. His paintings, she claims, suggest a preoccupation with the frailty of the human form which she relates to his anxieties over his own body and health.

Throughout his life Burne-Jones had frequent undiagnosed ‘episodes’ – lethargy, headaches, fainting fits, fatigue, depression and insomnia – which, to his frustration, often kept him from his work. While working on the larger Briar Rose paintings, he was becoming increasingly aware of ageing and anxious about his bodily demise: Kirsten Powell notes he feared he would die before the series was complete. In some ways, it might be said, he developed a heightened awareness of the relationship between external time and his own biological clock.

To live with chronic illness is to develop a unique relationship with time: we call this ‘crip time’. The term crip time stems from crip theory, and the radical reclamation of the word ‘cripple’ by disability activists in the 1970s. It describes the unique ways in which chronically ill and disabled people relate to time. In Feminist, Queer, Crip, Alison Kafer writes that crip time ‘requires re-imagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of ‘how long things take’ are based on very particular minds and bodies.’

I live with a condition which causes my energy levels to fluctuate – common for people with chronic illness. Some describe it as like living off a battery which drains easily and does not hold its charge. My body slips easily into a kind of primitive dormancy – heavy, but not restful. In the early stages I remember becoming keenly aware that the outside world was moving at a pace out of sync with my new mode of being. I was living in crip time, my main priority to survive.

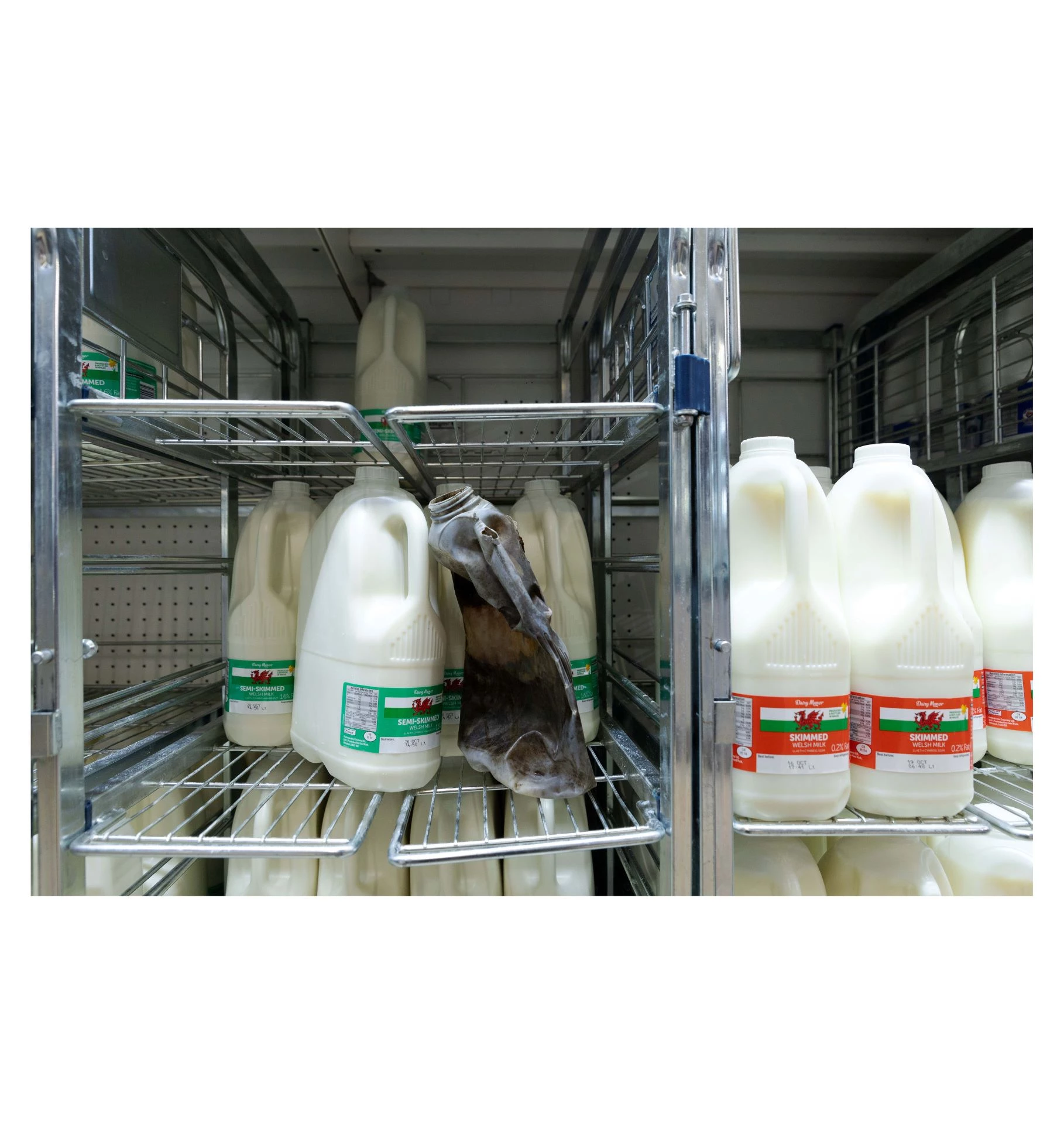

Crip time is a disruptor / You drift in and out of the normal patterning of the world / It challenges normative understandings of time; interrupts, interjects with its own strange logics / Asleep when you should be awake, awake when you should be asleep / Crip time refuses the idea that our bodies should march to the demands of a relentless capitalistic clock; recognises that sometimes, some bodies take longer / You move with different clocks, now. You measure time in flares, sleeps, bandages, appointments, scabs, spoons. How quickly you can fill an old jar with flakes of your own dead skin.

I recognise in the Briar Rose images something from my own experience of living in crip time: a certain rupturing of normative expectations of the relationship between bodies and time.

Deep in The Briar Wood, an androgynous prince stumbles on the bodies of five knights, asleep on the floor. Snapped-back necks and soft spines, ensnared in thorns – a warning. How long have they been there? A rose bush rages around them, circling, binding them slowly as they sleep among its sharp thorns. Over time it has pulled their shields from their bodies; hung them in its branches, jubilant trophies. The prince, to the left, is the only person awake. With glazed eyes he stands statue-still, sword slack at his side - stunned perhaps, or contemplating his next move. But he can’t afford to wait. Thorny branches are already winding around his feet, like snakes.

You’ve been for some time lying in your bed - months, minutes, maybe years - with a condition that doesn’t exist. And you know it doesn’t exist because the doctors say it doesn’t exist, because they haven’t found it yet. A fabrication, a mystery, they say. How strange. But you exist, your pain exists, and so you wait some more to be found.

Crip time is also time spent waiting. Waiting for appointments, waiting for results. Waiting to be put on waiting lists. Waiting for diagnosis, for treatment, for medical research to catch up with our bodies. Some people are kept waiting longer than others. Last year a report ‘Waiting for a Way Forward’ by the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists found over half a million women, or those assigned female at birth, are waiting to be treated for conditions like fibroids, endometriosis, or menopause care in the UK. Medical misogyny at work.

You move slowly, ever slower, as you wait to be seen while the world moves on apace, hustling around you in strange strangling loops while, still. You wait. Inside, lesions and scars grow thick in your pelvic region. Swelling, reshaping, binding your organs together. Your ovaries are now stuck to your uterus wall, the doctor explains. Pulled from here – to here – over time. Very concerning, complex, yes. Surgery, adhesions, excisions, scans. Endometrial pain like a thick tangle of thorns. Sharp teeth piercing tender tissues. Still, you wait.

Endometriosis affects 1 in 10, and is on the NHS list of the 20 most painful health conditions in the UK but it takes an average of seven years to get a formal diagnosis. Meanwhile, the disease progresses meaning that for many women, by the time they eventually get diagnoses, the condition has become even more severe and complex to treat.

Like all good fairy tales - grim.

In The Council Chambers, the sleeping King slumps forward on his throne still holding an administrative scroll, future plans suspended. A stiff mantle around his shoulders props him up, his royal head drooping under a weighty crown. Council advisors are asleep on the floor, a heap of listless bodies. On a table to the right is a large hourglass, the sands of time stilled. But even in the stillness, there is still movement, still growth. Thorny tendrils twine around the bodies in slow, lazy loops.

This image challenges normative understandings of how bodies move through time: strange new logics hold court. In Interlacings, Caroline Arscott notes that - as in Alfred Tennyson’s poem The Day-dream - the King’s 100-year-old beard trails down to his lap, snow white, still growing though his body is dormant, frozen in time. To the Victorians, beards and body hair were signs of wisdom and health.

You lay for hours in the bath. Sweet steam of rosehip and lavender, water creamy with breast milk sent by a friend who read it could – perhaps – help. You dunk your head under, see how long you can hold your breath. Your heartbeat slows – slowly - slower. You are losing your hair. You arrange the dark strands on the lip of the bath: like calligraphy, elegant, but nightmarish too. You shed dead skin, more each day. Flakes float on the water’s surface, a stippling of cells. Your body is killing off parts of itself to survive. A thousand tiny deaths to sustain a single life. The letting go a sacred offering: a soft nod to the organic passing of time.

Crip time gave me a new sympathy for the ways in which the body moves through time: a complex interplay of growth and decline, surrender and renewal, submission and noncompliance. Some parts suspend for others to thrive: sometimes, new symptoms are signs. The body’s strange wisdoms on how to survive.

We’re in The Garden Court, now. Six weavers asleep, their bodies draped around a garden fountain and a wooden loom. Rose briars - their branches heavy with blossoms - surround them in loose loops, following the arched shape of their backs. Their bodies are collapsed and heavy, but their bare feet and arms are gracefully arranged. Ballet hands, delicate feet: a beat of bare limbs. To the right, one of the weavers is folded forward over the loom, her body a lazy Z. Labour paused.

We will all, at some point, need to pause our life’s labours, for any number of reasons. Cancer, covid, a cold, a chronic condition. Bereavement, burn-out. Sometimes just to breathe. Some pauses are temporary, others lifelong. Often it is less of a ‘pause’, and more a shifting of our efforts and energy to other forms of labour. Becoming parents or carers. Turning inwards, tending to ourselves. But today’s economy tells us a body is of little value unless it’s in constant service to capitalism and profit. That our main purpose in life is to work faster, harder, more (for less, less, less). That bodies that can’t keep up are worth less, even worthless.

Disability Rights activists have recently warned that the new assisted dying bill in the UK could have a ‘serious and profound negative impact’ on how disabled people’s lives are perceived and valued, further entrenching the idea that disabled bodies are ‘expendable’ when not in service. But look at the weavers here - their bodies folded and temporarily out-of-service. Look how necessary, how beautiful they are. Life for life’s sake: is that such a radical idea?

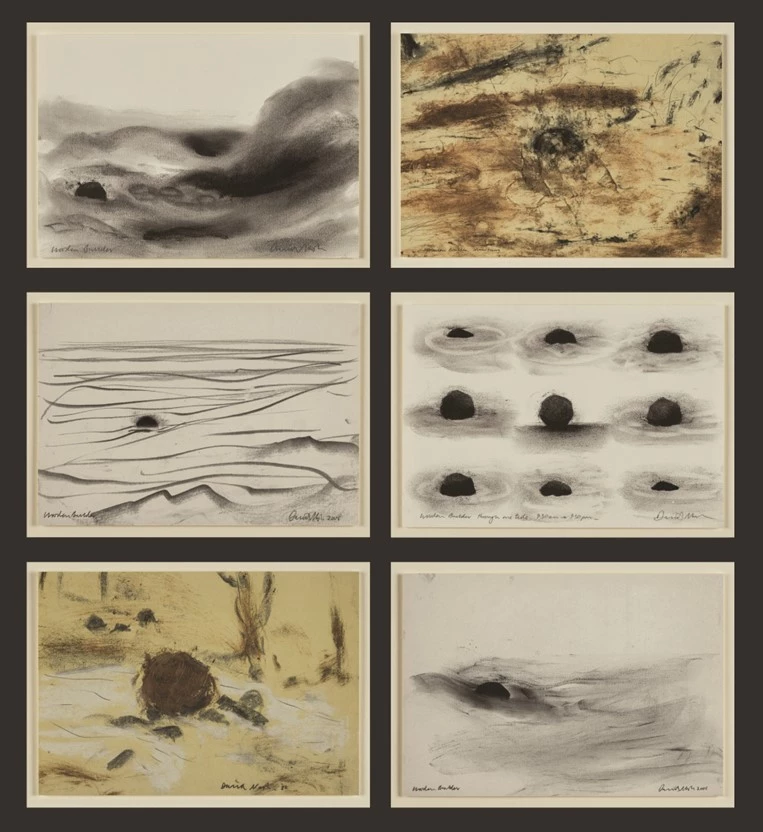

Burne-Jones worked on the Briar Rose theme for decades. It was a subject he returned to time and again, producing several different versions - ceramic tiles, paintings, prints – an ongoing obsession which often left him exhausted. Keenly aware of ageing, he was in some ways in a self-imposed race against his own body clock. At the same time, he embraced the slowness of creation, taking care over the intricate details, textures and surfaces; his work a protest against mass-production, an act of devotion to Art. Like crip time, these works suggest new ways of understanding the relationship between bodies and time. The slow violence of the wait. The beauty in the pause. How bodies move to their own rhythms and logic: the strange organic passages of time.

With gratitude to Kaite O’Reilly for valuable feedback on an early draft, as part of Reinventing the Protagonist 2024-5, an opportunity organised by Literature Wales in partnership with Disability Arts Cymru.

Steph Roberts is a curator, writer and researcher whose work explores the intersections between the visual arts, words, and disability justice. Previously Senior Curator of Historic Art at Amgueddfa Cymru, she now works with artists, museums, galleries and others across Wales and beyond to challenge and disrupt systems of exclusion, and highlight neglected narratives and voices. www.stephcelf.co.uk.

References:

Anderson, A., Edward Burne-Jones The Perseus Series (Sansom & co, 2018)

Arscott, C., William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings (Yale University Press, 2008)

Kafer, A., Feminist, Queer, Crip (Indiana University Press, 2013)

Powell, K., ‘Burne-Jones and the Legend of the Briar Rose’ Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies (May 1986)

Samuels, E., ‘Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time’, Disability Studies Quarterly (Summer 2017)

1‘Les Artistes de l’âme’, Le Journal, Feb 23 1896, cited in Anderson, p.10

This work was commissioned as a collaboration between CELF and Disability Arts Cymru.