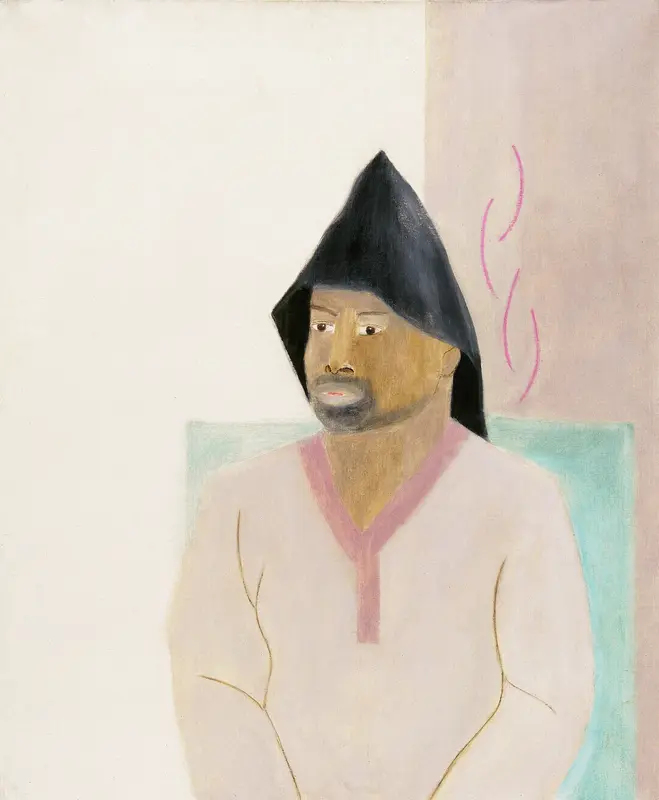

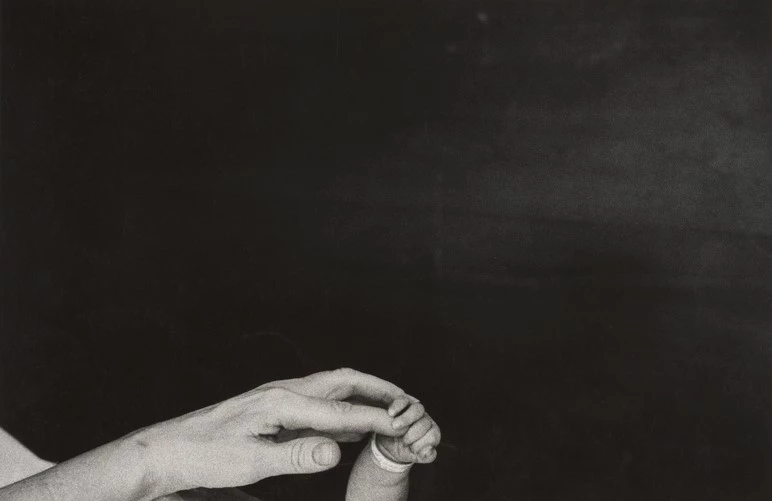

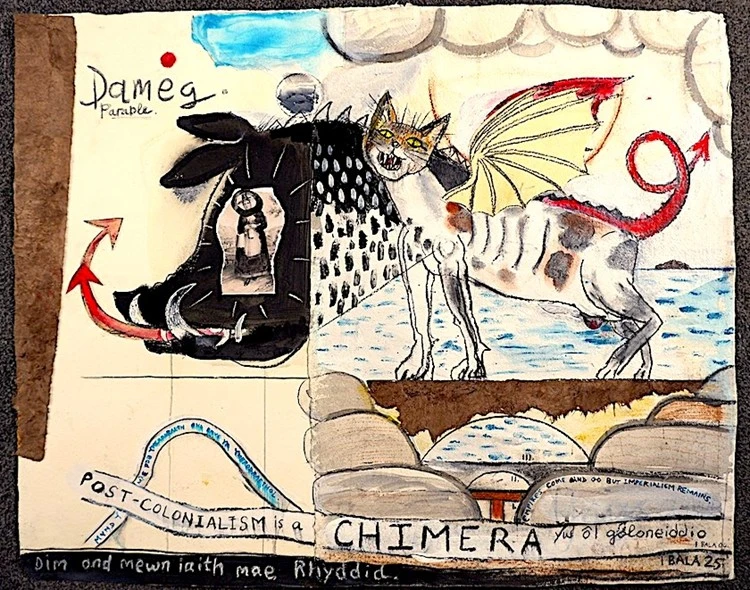

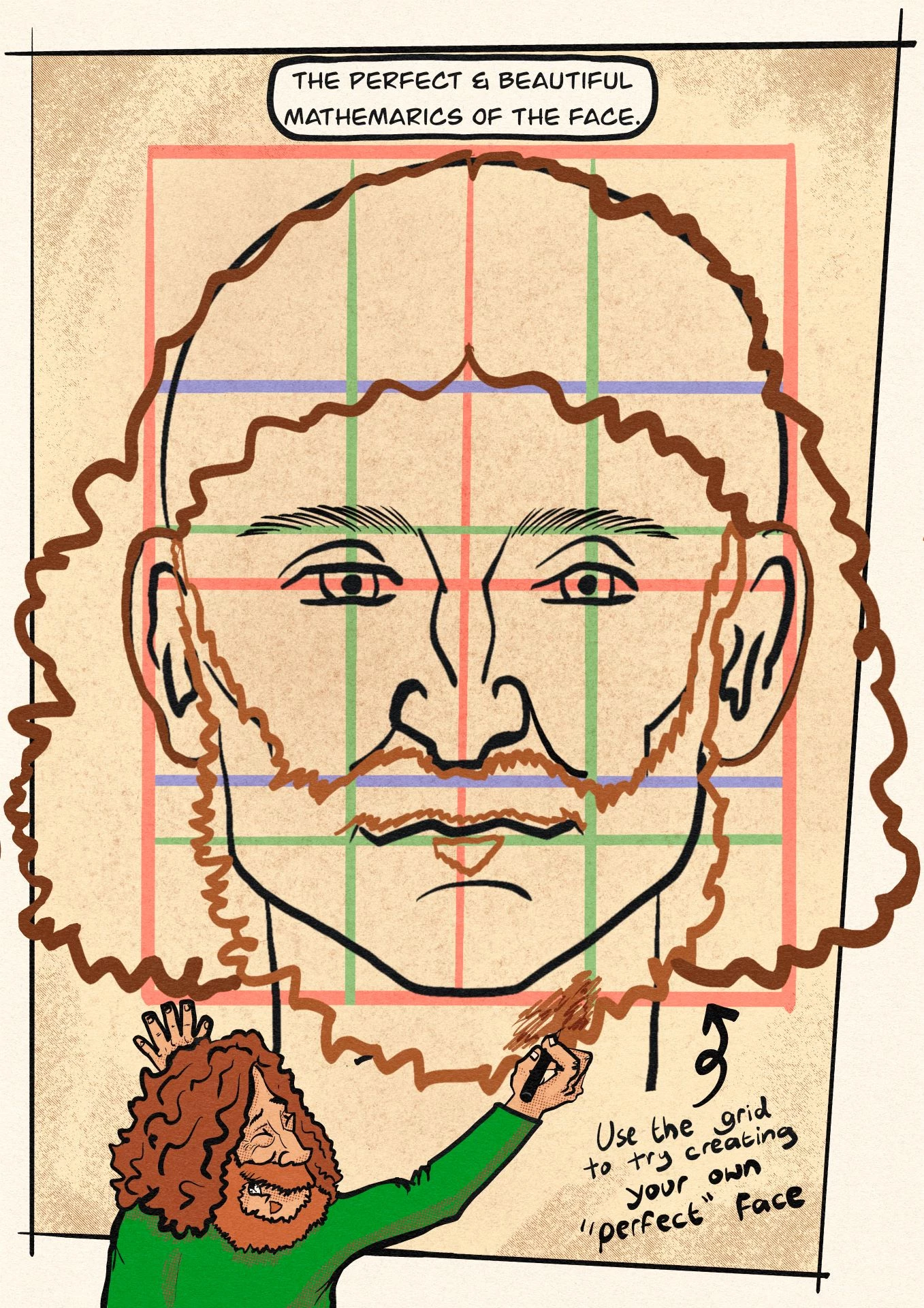

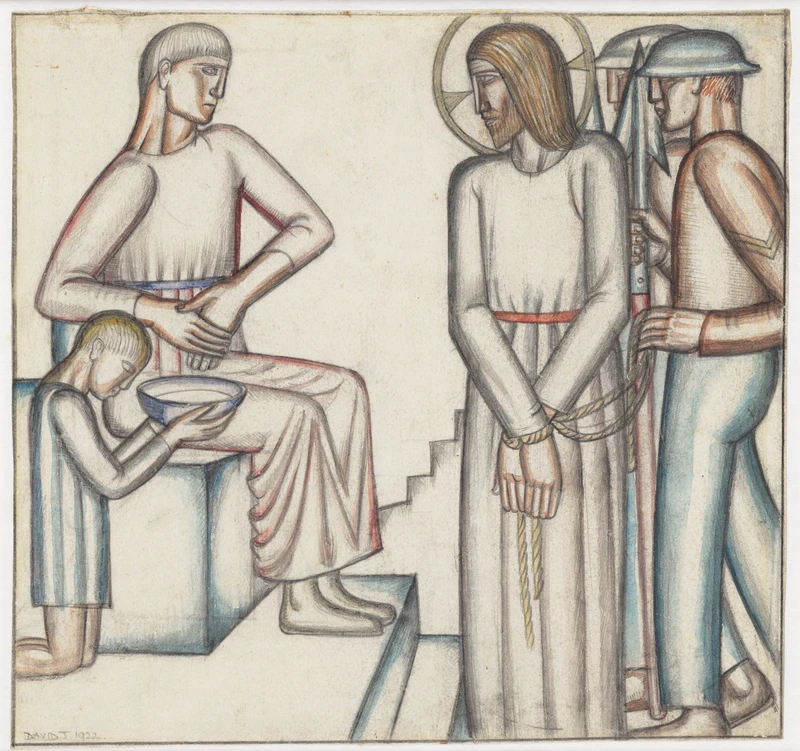

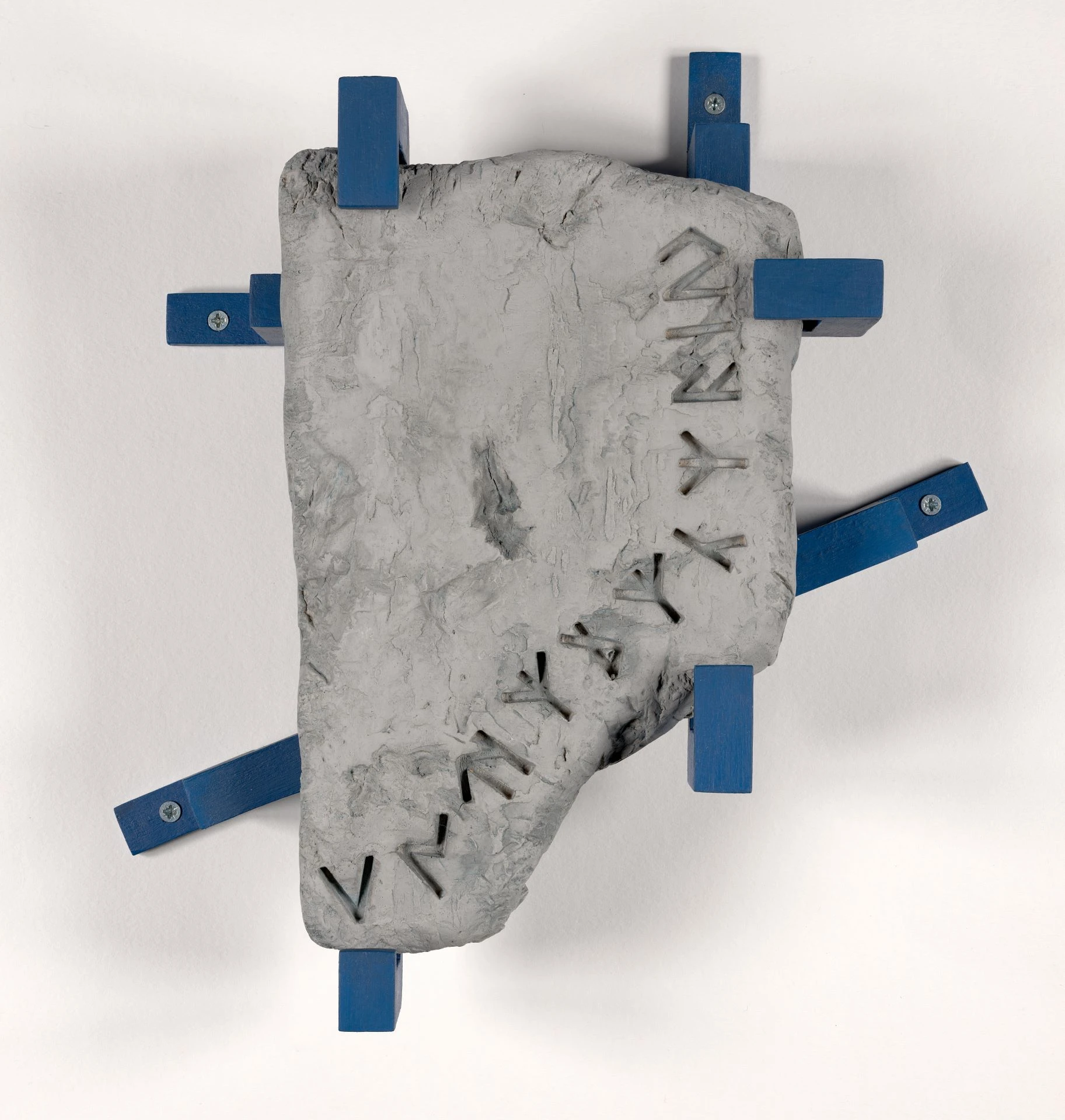

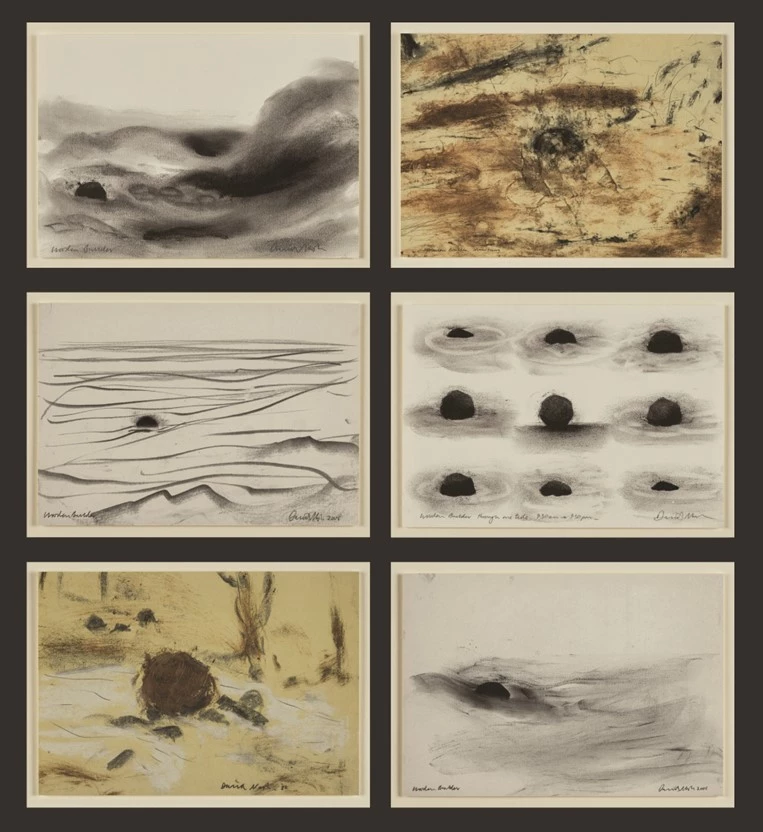

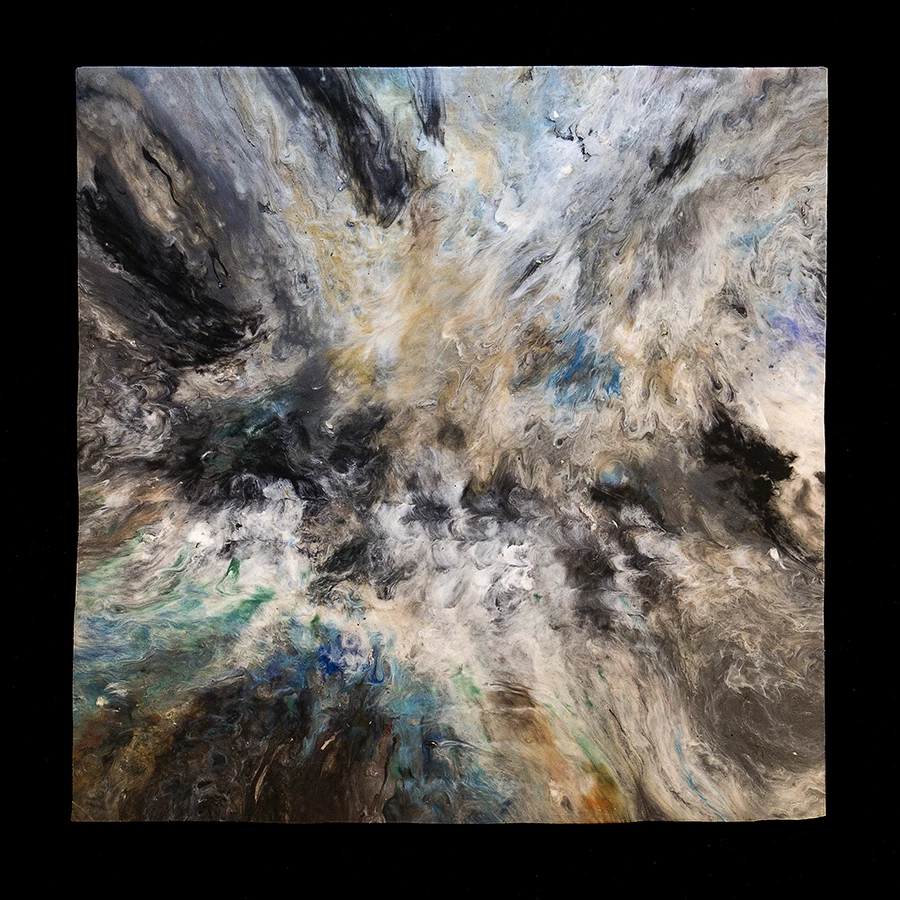

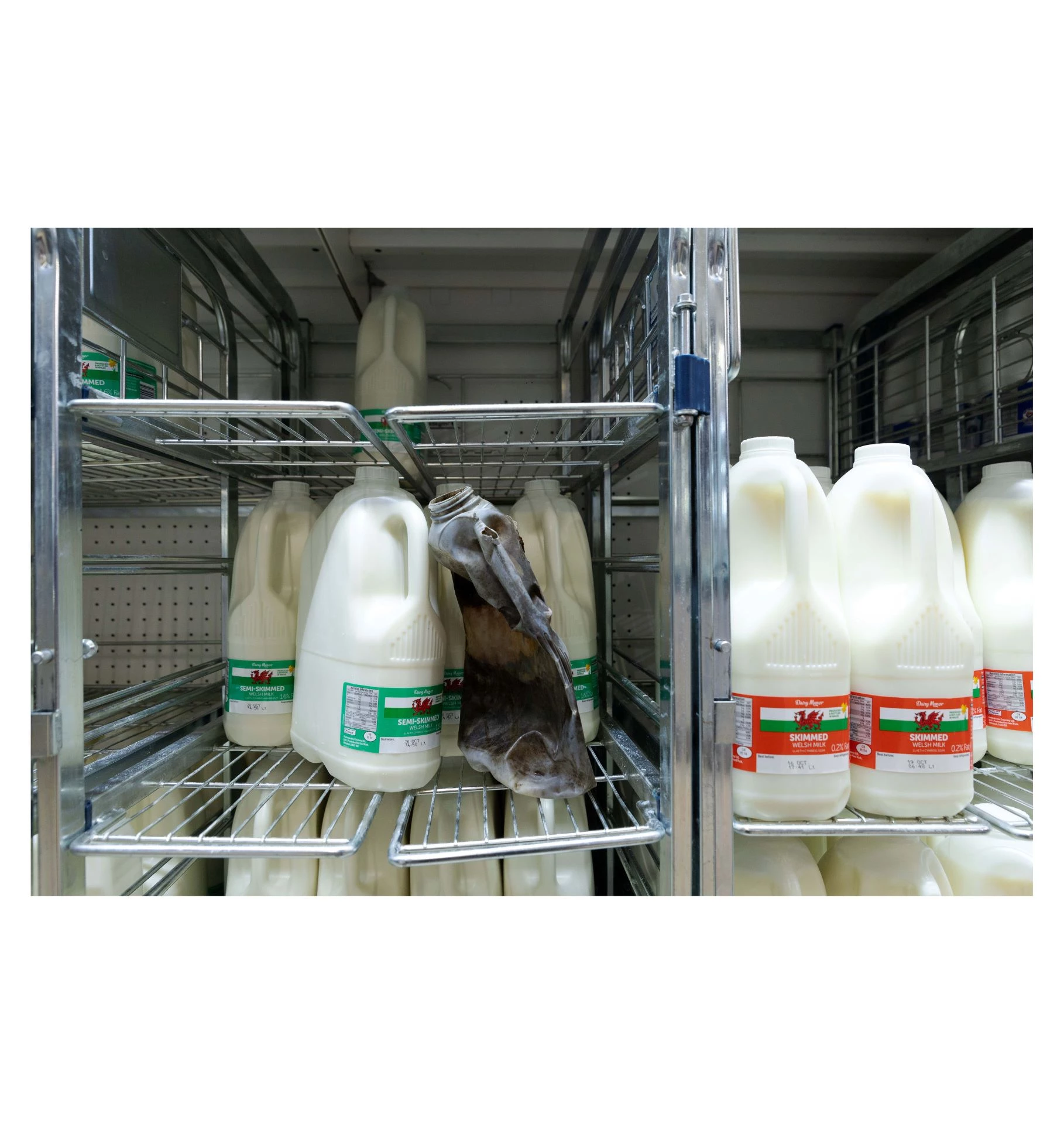

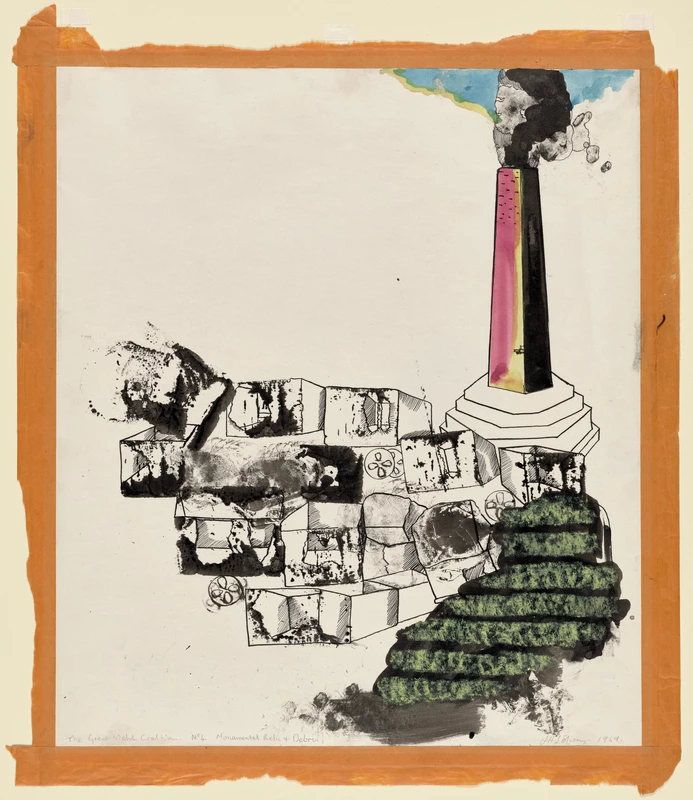

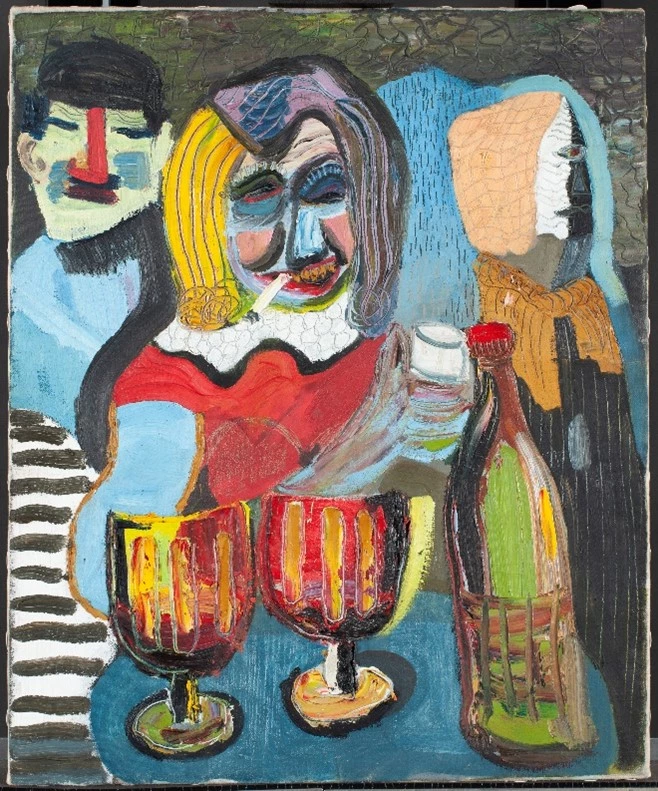

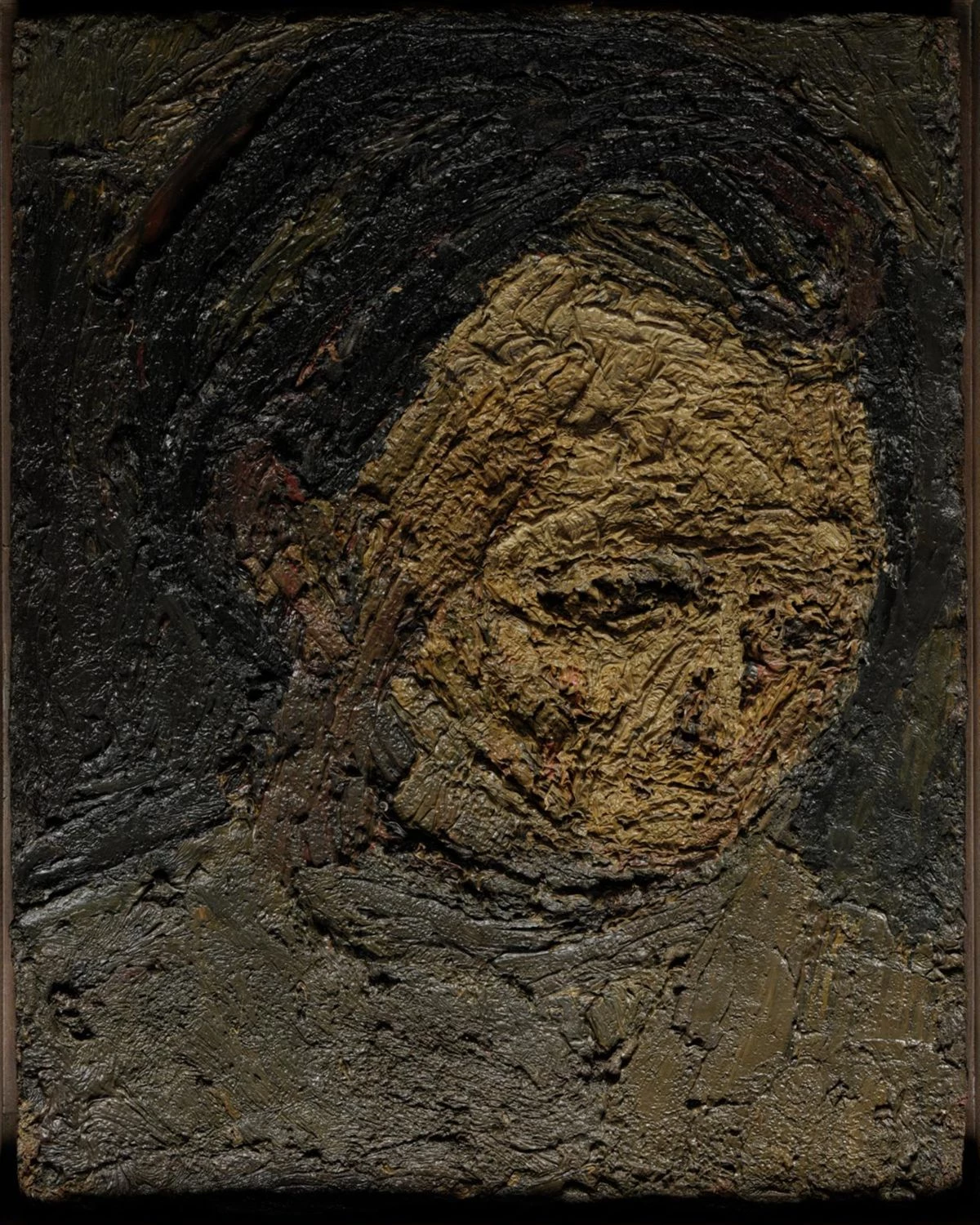

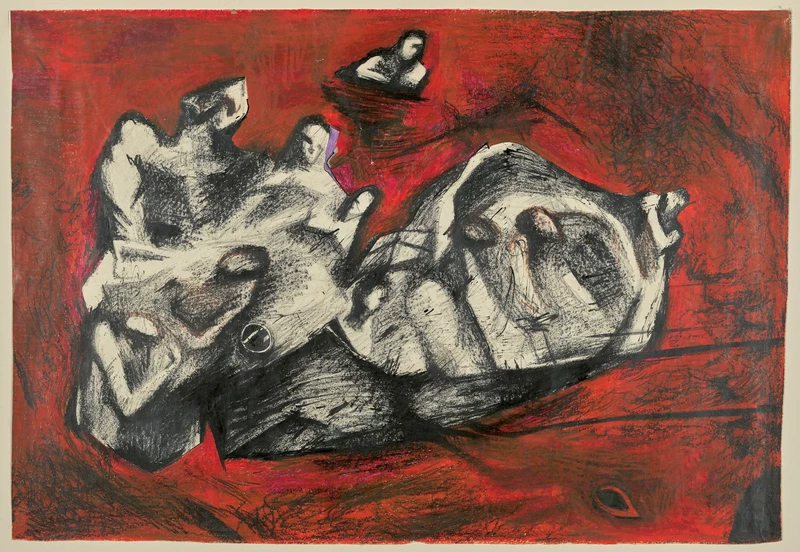

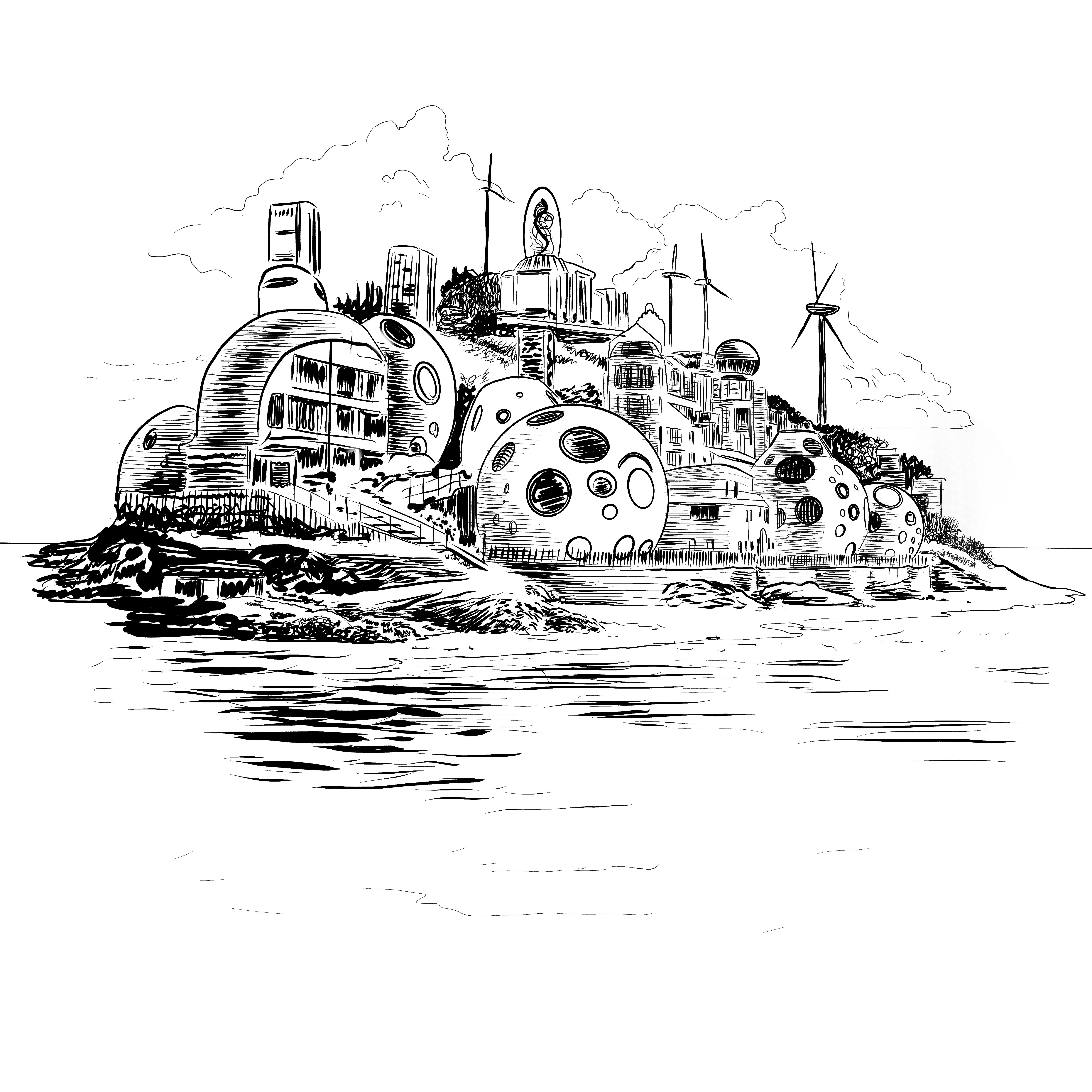

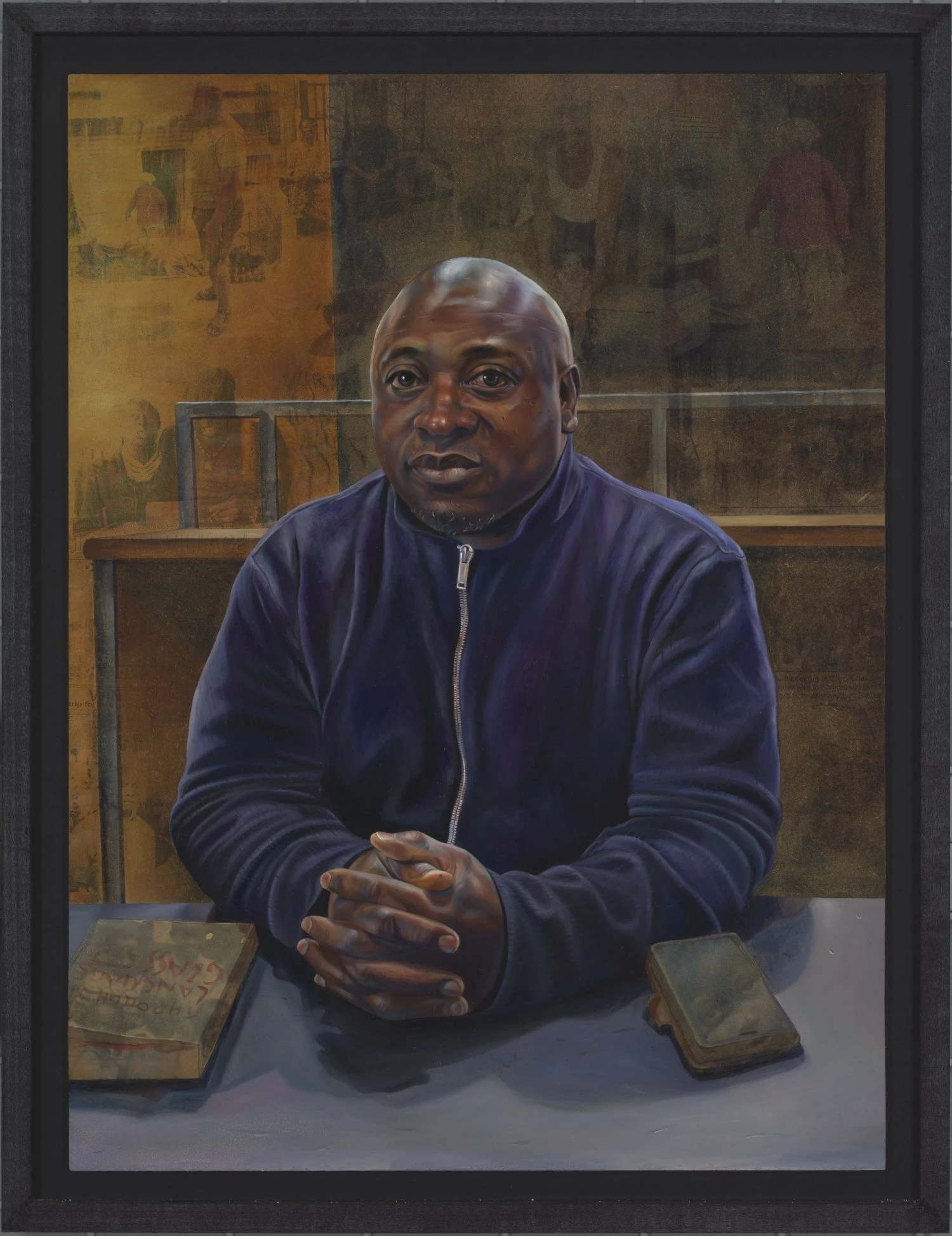

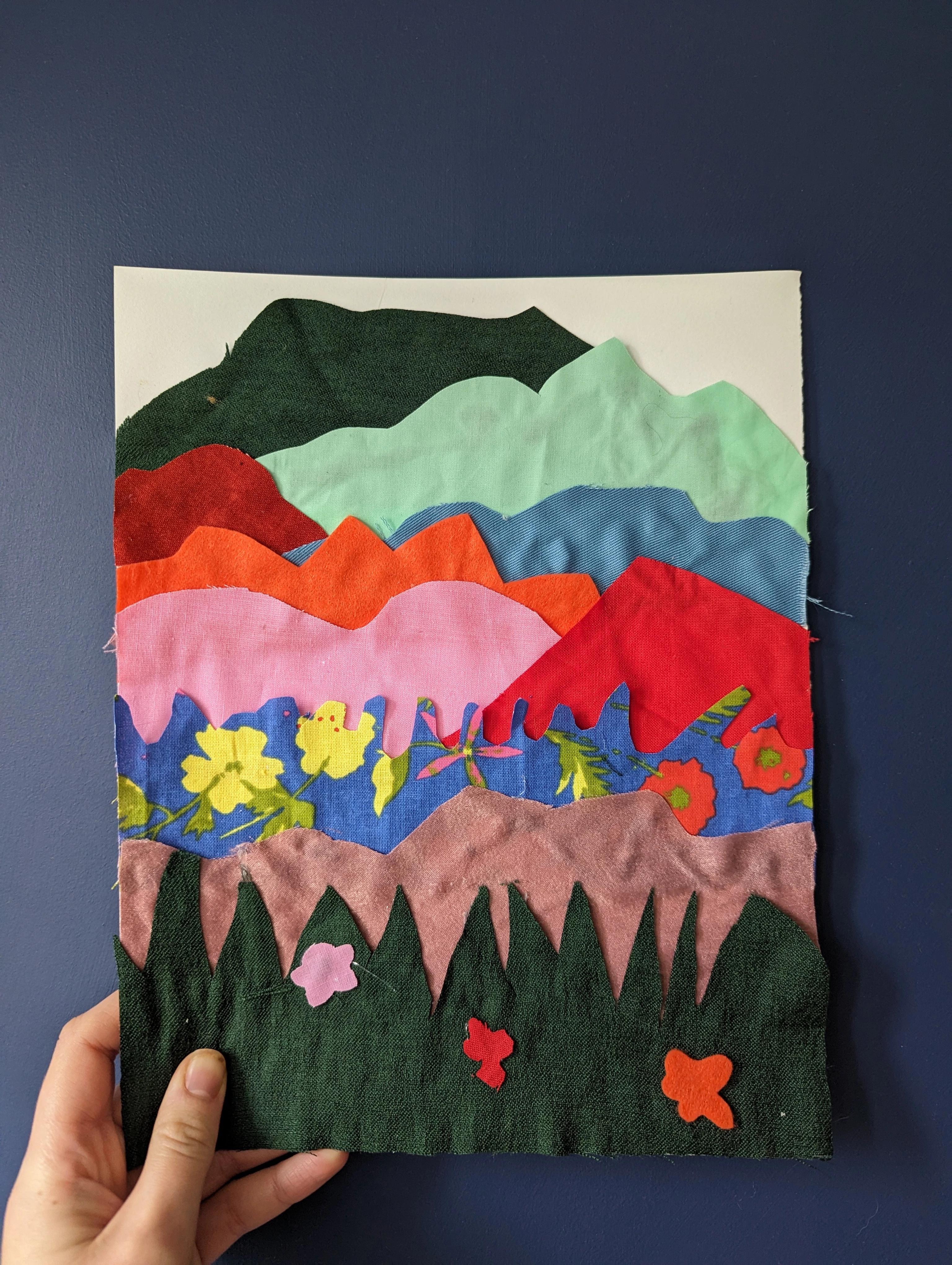

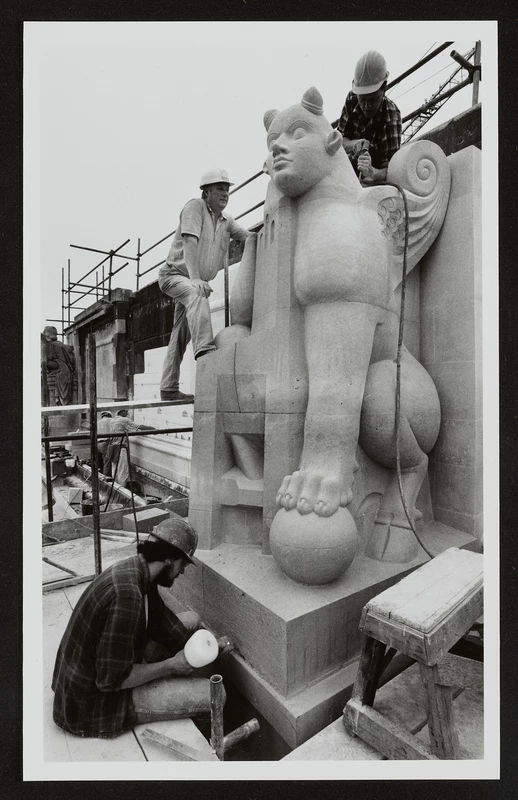

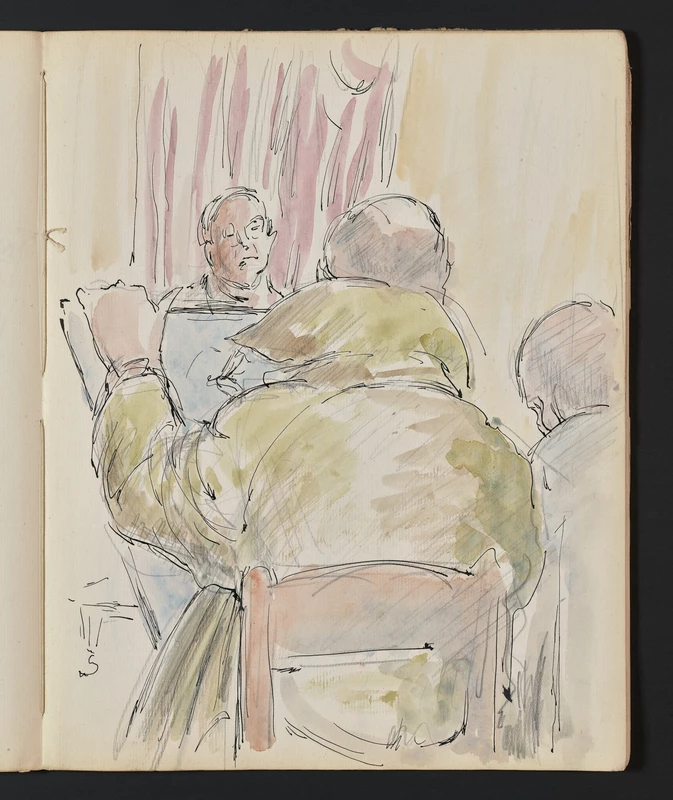

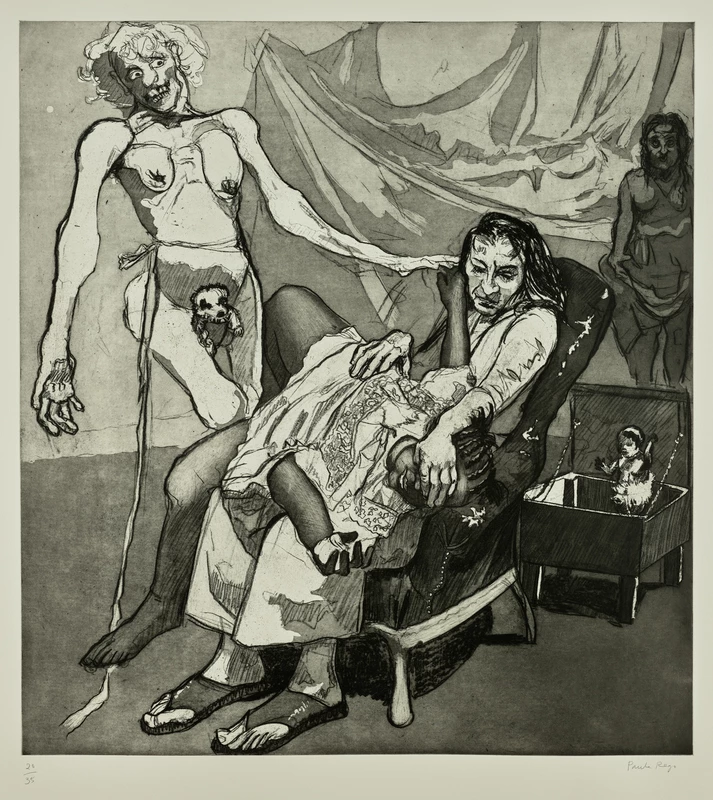

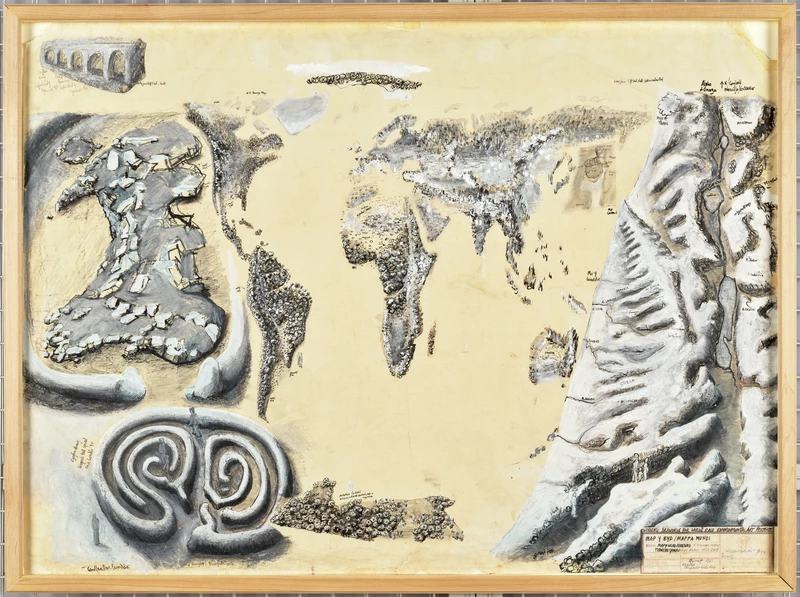

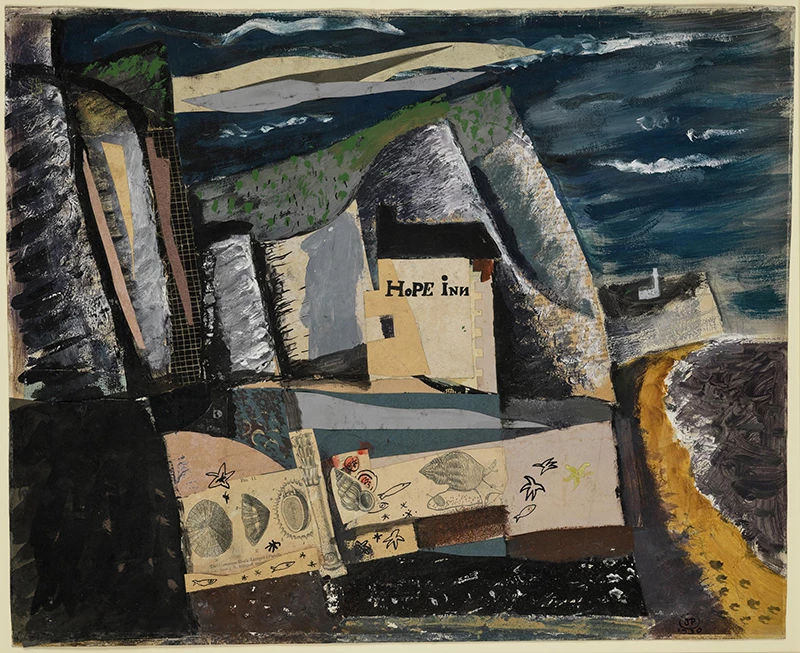

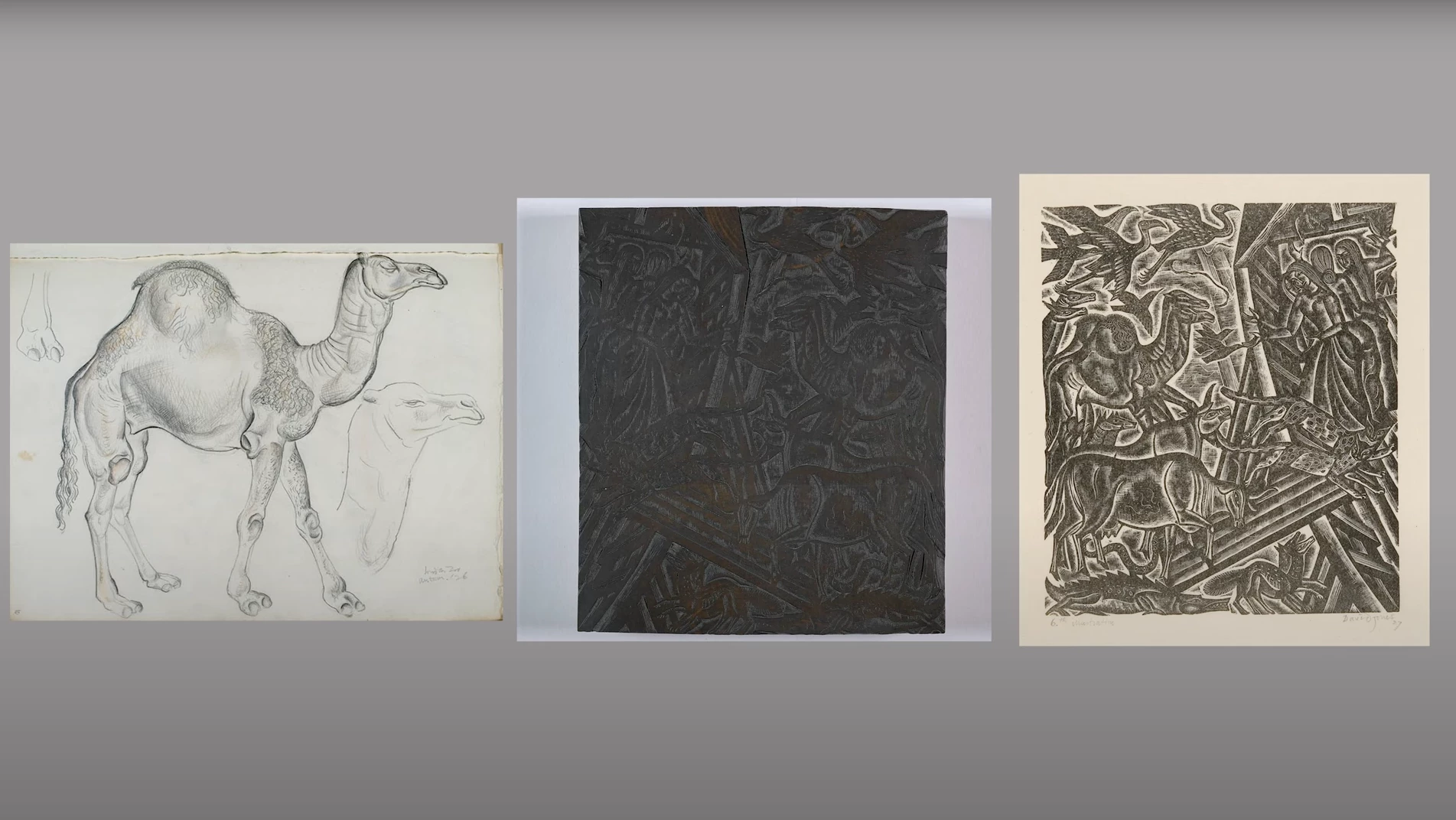

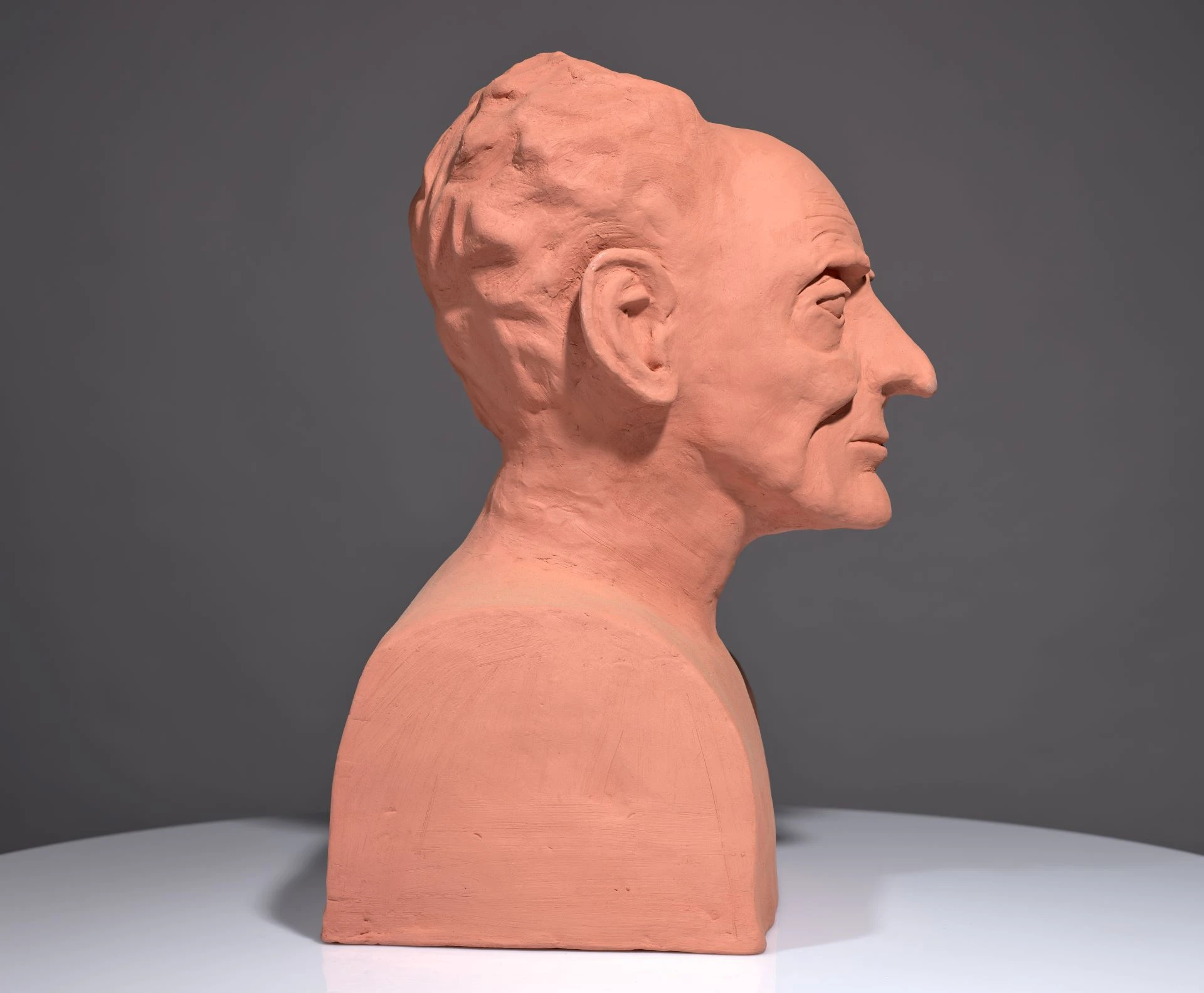

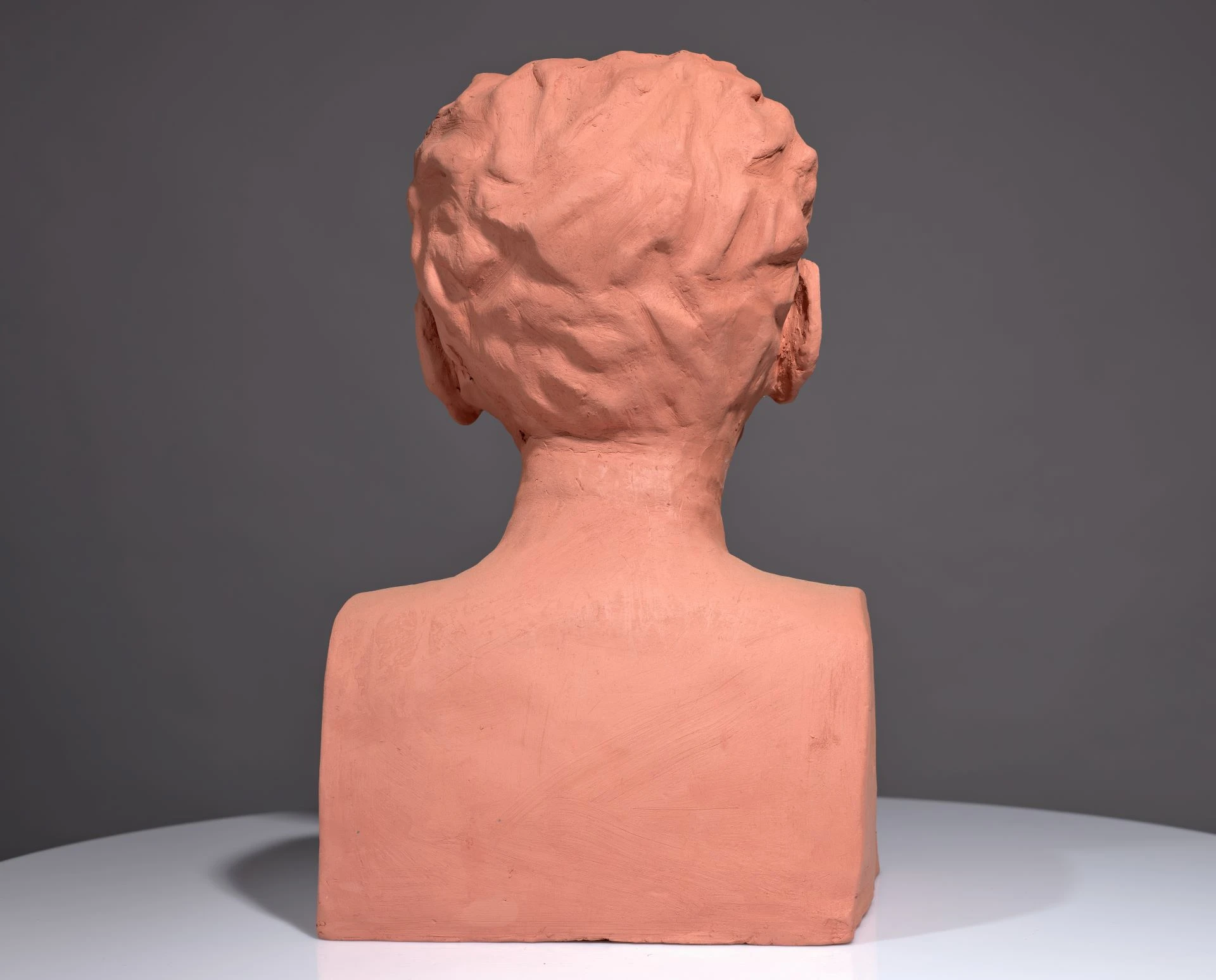

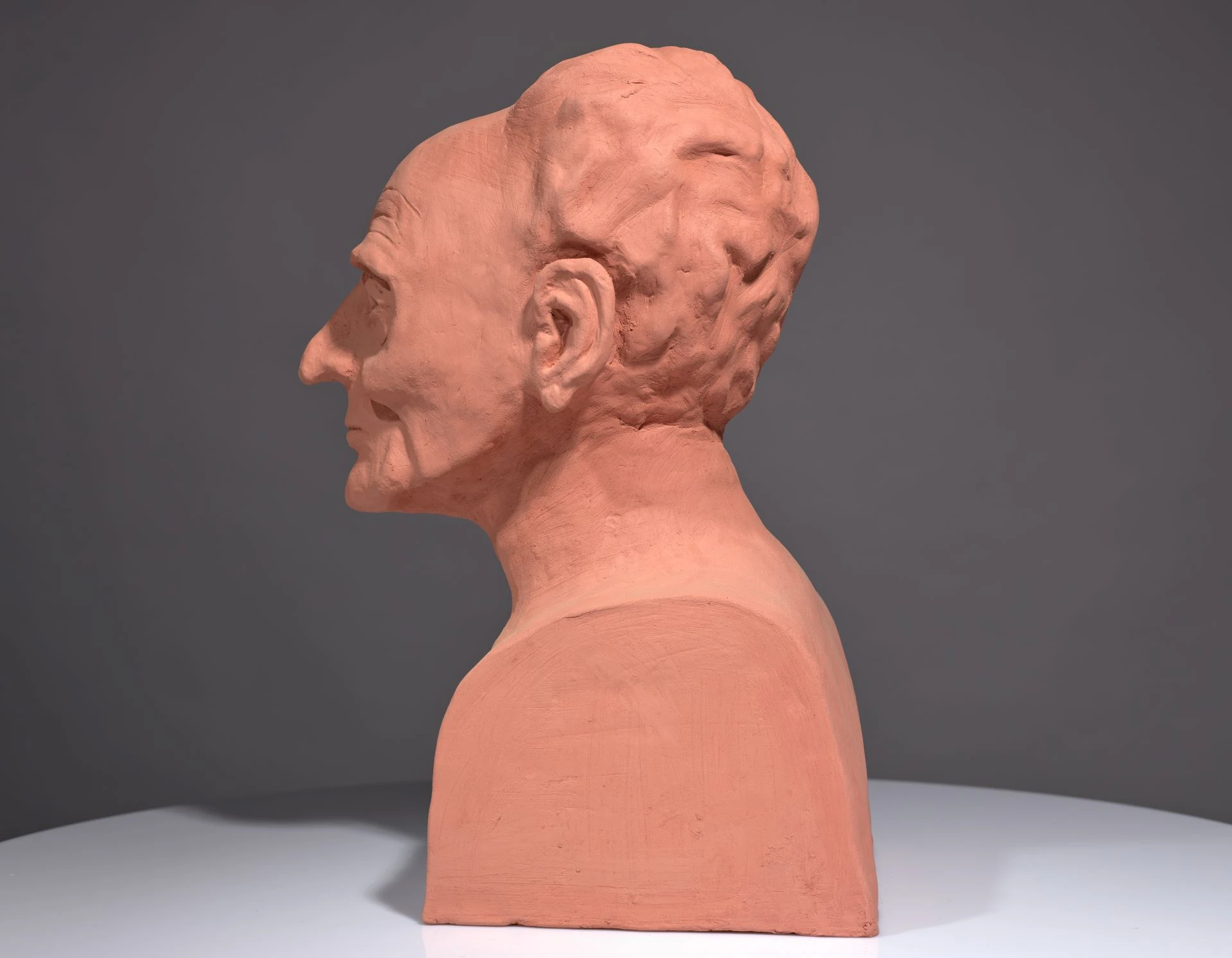

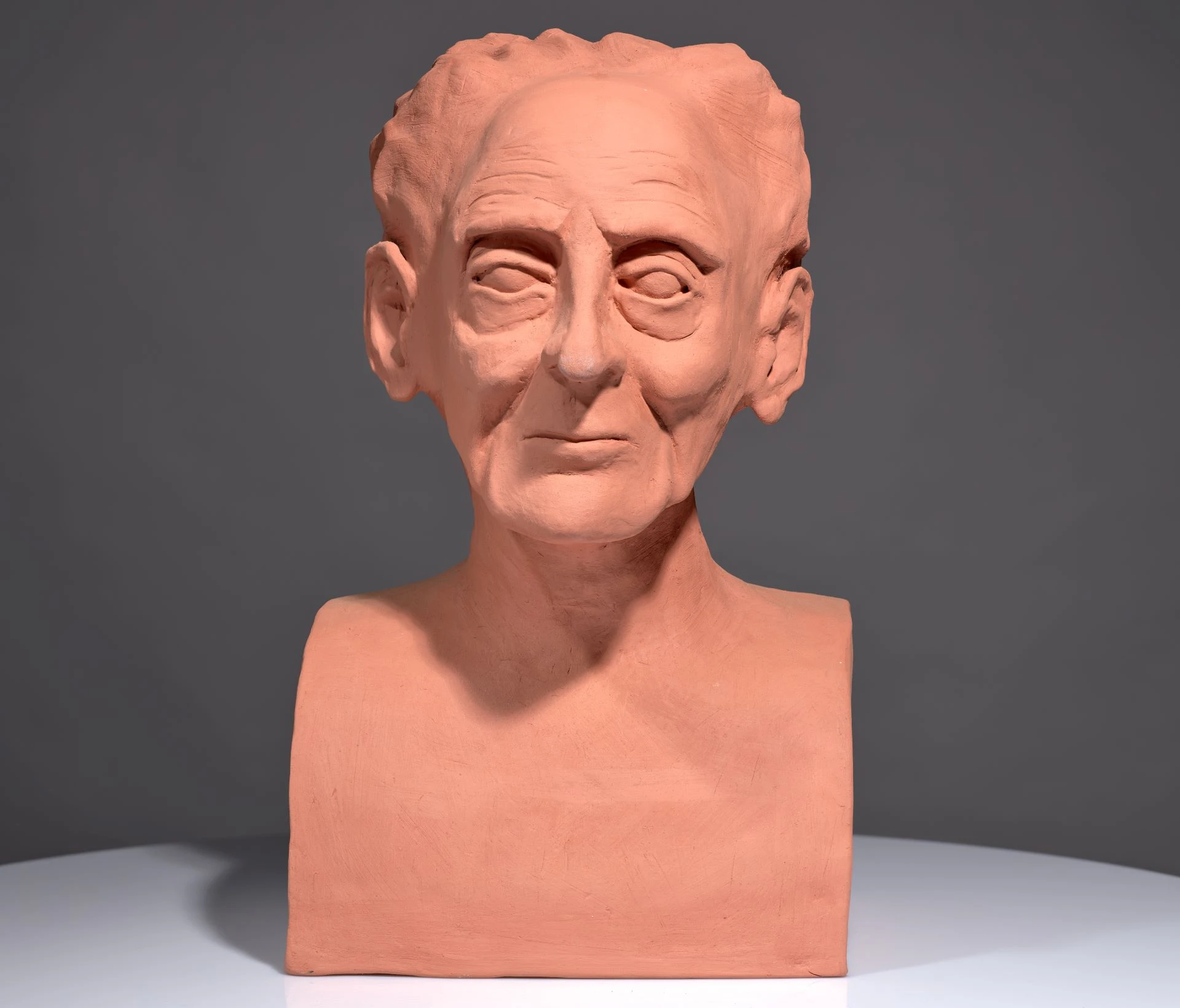

EASTWOOD, Paul, Saunders Lewis © Paul Eastwood, Photography by Rhian Israel

The Shadow of Saunders’s Statue

by Owain Lewis

The act of sculpting someone’s statue is one that locks the presence and the personhood of that individual in a particular time and place. Portrayed in clay, bronze or marble, the person in question becomes an idol to be observed, an object to be considered and displayed in a particular context.

It is the fate of the subject of every statue to shift from being an active person in the world to being an effigy that must sit mute in that same world. The diligent, the industrious, the able and the famous become static objects caught in time. They are installed to be displayed and admired, celebrated and condemned, studied as pieces of art to be scrutinised by the ages. Although the sculptor’s craft can hint at the nature of this person, often the ideas and actions which prompted the piece are absent from the object itself.

Yet there are to statues symbolic significances which are broader than their plain objectness and there is to that objectness itself a broader significance. Statues are purposefully long-lasting things, records of a life made solid so that it can transcend time. Due to their literally immovable and permanent nature in a protean world increasingly unsure of fundamental truths, often statues will inspire discussions and heated arguments regarding not only the person in question but also society’s ideas regarding values, politics, and history. In this regard our reaction to statues is subjective and also reflects broader discourses playing out in society.

Recently movements such as BLM and others have once more raised awareness of some of our most ‘problematic’ historical figures, actively demolishing the statues of those who partook of, and profited from, the horrors of slavery. There is a responsibility therefore to look anew at our statues and to publish in an accessible medium any biographical elements of their subjects that could be considered problematic or would cause people pain.

There is a need for a different explanation of statues, an elaboration of sorts on the biography of the figure in question that not only justifies the existence of the artefact but also places it in a context which answers the demands of the present as well as trying to grasp questions such as: Who was this person? Why is there a statue of them? Did they do any good in the world? Is there something I should know about them that the statue doesn’t show?

Rather than attempting to present a comprehensive biography of Saunders Lewis, the aim of this piece is to discuss one particular element of it, namely the shadow cast by some antisemitic comments in his written work, and the public discourses that have arisen regarding those comments. I will first look at a few examples of Saunders Lewis’s comments and then how those contributing to both sides of the debate on these comments are willing, in effect, to turn Saunders Lewis into a kind of conceptual effigy. As a result of this conversation, Lewis becomes a stationary ideological idol with a set form, his purported worldview as unmovable as the statues that portray him. Often this is done at the expense of more complicated truths, less ready to be moulded and set, which are often contradictory and messy.

There are several examples that could be used to show antisemitism in Saunders Lewis’ work. Without trying to diminish in any way the significance of other remarks of his but accepting the need to be brief while also doing the topic at hand justice, I will focus on two notable examples here.

EASTWOOD, Paul, Saunders Lewis © Paul Eastwood, Photography by Rhian Israel

EASTWOOD, Paul, Saunders Lewis © Paul Eastwood, Photography by Rhian Israel

EASTWOOD, Paul, Saunders Lewis © Paul Eastwood, Photography by Rhian Israel

The most infamous example comes from the poem ‘Y Dilyw 1939’ (‘The Deluge 1939’) published in Byd a Betws (1941). The poem rails against the cultural, moral, spiritual, and national decline that Lewis sees in the south Wales valleys in the decade following the Great Depression of 1929. He finds in the valleys a hopeless nihility caused by global economic forces, and the figure of the villainous and remorseless capitalist Jew is placed at the root of this nothingess:

- ‘Then, on Olympus, in Wall Street, nineteen hundred and twenty-nine,

- At their infinitely scientific task of guiding the profits of fate,

- The gods determined, their feet in the Aubusson carpet

- And their Hebrew nostrils in the quarter’s statistics,

- That the day had come to lessen credit through the universe of gold.’

- (1941, p.10, translation by Joseph P. Clancy from ‘Selected poems’, the University of Wales Press published volume of Lewis’s poems in translation from 1993, p.11)

There is evident antisemitism here. It shows Saunders Lewis’s expression of a particular worldview that upholds the narrative of Jews as an all-powerful cabal who can somehow control global capital. The Jews of New York are portrayed as gods of the modern world, as if the fate of nations sat in the palm of their hand. It is impossible to deny the interpretation of the poem as one that expresses antisemitic theories and tropes while utilising the image of the Jew and his so-called unfettered international power as a scapegoat. Indeed, this treatment of Jews is part of a wider pattern of Lewis’s work for a period.

Beyond ‘Y Dilyw’, there are also remarks about Jews which could be perceived as antisemitic in columns by Saunders Lewis in the paper Y Ddraig Goch. Amongst these, many have mentioned an article that appears on the front of the paper in June 1933 under the headline ‘Propoganda’r Papurau Saesnig’ (The Propaganda of the English Papers). Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany is discussed, along with his economic policies targeting Jews and the reaction of the British press to these events. Saunders Lewis says:

Once again, there is a portrayal of powerful international Jews, this time buying the influence of the British press in order to move public opinion against Germany. This is without doubt, another form of a common antisemitic trope of the time. Although he mentions the persecution of the Jews and refers to the fact that the ‘innocent’ as well as the ‘harmful’ will be caught in the nets of the policy, the effect of this apparent distinction between good and bad Jews is to tacitly justify the rationale for persecution.

The above example is useful in showing us some of the features of the discussion regarding Saunders Lewis’s antisemitism. Meredydd Evans wholly rejects the interpretation:

Yet Lewis’s inability to note in a clear and unambiguous way the fundamental racism of the policy is problematic to say the least. The belief that German Jews, who formed around 1% of the population in 1933, were in possession of riches far greater per head of the population than other Germans is one of the myths that was used by the Nazis to justify racist laws and the persecution that led in turn to the Holocaust.

One could argue that Lewis was unaware of the unrelenting horrors that were to face the Jews of Germany and the rest of Europe. Similarly one could argue that the intention of the article was not to make a direct point about the schemes of Jewish capitalists so much as to highlight how the press was trying to influence the population to prepare them for war (Evans, 1989, pp.41-42). Yet Lewis’s inability to condemn what was happening in Germany in 1933 and his readiness to utilise the trope of the moneyed Jew is unquestionably a mark against him and is evidence of his antisemitic attitudes at this time.

Certainly, as Grahame Davies has shown, later plays by Saunders Lewis such as ‘Brad’, ‘1938’ and ‘Esther’ can be seen as attempts to put right the wrongs done by him to Jews in his previous remarks and as a kind of apology for his earlier articles and poems (2002, p.32) Davies notes the attempt in Esther particularly to link the histories of the Jews and the Welsh:

It is not the purpose of this piece to comment on the degree to which these attempts make right for previous statements, (they do not, after all, constitute explicit apologies or expressions of repentance) but they should be noted, as they do, seemingly, signify a conscious change later in his life of Lewis’s public attitude towards Jews.

Looked at from the perspective of his wider work, although the above comments are clearly antisemitic, interpreting what their exact intention, meaning and significance are in relation to Saunders Lewis’s broader thought is complicated and is for another piece. Based on the historical evidence available to us, we can unambiguously say that Saunders Lewis made antisemitic remarks, and he seemingly held and expressed antisemitic views for a period. Later there is also evidence that he rejected the ideas that inspired these comments, and attempted to make amends for them. The situation is therefore somewhat ambiguous: which element of Saunders Lewis’s work should be highlighted, what version of the author is the correct one to remember?

The effect of this ambiguity is that there have been several occasions where the discussion about whether or not Saunders Lewis was on the one hand an innate antisemite or somehow on the other hand taking part in public discourse which was fashionable at the time and was therefore somehow, some would argue, more acceptable or understandable.

His columns especially are subject to disagreement to the extent that their significance can be interpreted in different ways and individuals in turn have chosen to use them to argue in favour of and against considering Saunders Lewis to be a virulent antisemite. For Grahame Davies the columns show that Lewis suggested that tales of persecution of the Jews were ‘false propaganda’ (1997, p.69) and were part of a specific reaction to the modern world of the type seen in the works of Chesterton, Belloc and T. S. Eliot:

Marc Edwards argues in his recent article in O’r Pedwar Gwynt:

On the other hand Meredydd Evans argues, in his assessment of Lewis’s columns in Y Ddraig Goch, that examples of his antisemitism are rare, and that there are also many examples where he displays empathy towards Jews (1989).

This discussion, and the interpretations which different readers choose to follow, are often governed by wider political persuasions, and the need to condemn or defend Saunders Lewis’s legacy as a key figure in twentieth century Welsh history as well as the emergence of the Welsh and Welsh Language focused nationalism which he represents. The discourse turns from one which engages directly with the facts of Lewis’s work, to a different debate about the nature of Wales and Welsh nationalism. As a result, often the conversation veers from trying to find the truth of the matter towards partisan dispute that does not give enough attention to the central question of Saunders Lewis’s antisemitism.

Two notable examples of this tendency can be noted here briefly. The first comes after the publication of D. Tecwyn Lloyd’s biography John Saunders Lewis: Y Gyfrol Gyntaf in 1988. There was a public discussion about the validity of the accusation against Saunders Lewis following comments by the author about his attitudes towards Jews. Contributions were made by Dafydd Glyn Jones, Ned Thomas, Dafydd Elis Thomas and others as part of that discussion, and these comments in turn are what inspired Meredydd Evans to write his defence of Lewis.

The second, more recent example, comes in the form of a public debate that was primarily held on the website of the Institute of Welsh Affairs following the publication of Richard Wyn Jones’s book Y Blaid Ffasgaidd yng Nghymru: Plaid Cymru a’r Cyhuddiad o Ffasgaeth in 2013 (published in English the following year under the title The Fascist Party in Wales? Plaid Cymru, Welsh Nationalism and the Accusation of Fascism). As the title suggests, the subject of Richard Wyn Jones’s book is the historical accusation of fascism against Plaid Cymru, where he provides an account of some of the main figures of Plaid Cymru in the twentieth century, Saunders Lewis among them, and rejects the accusation of fascism.

Following the publication of the book, Tim Williams wrote an article on the IWA website condemning the historical analysis of the book, focusing on Saunders Lewis. Williams’s analysis is fiery, but to surmise he is critical of the attempt, as he sees it:

Tim Williams locates the argument about the alleged fascism and the antisemitism of Lewis self consciously in the politics of the present. Yet, he also seems to claim that Saunders Lewis is no longer relevant to contemporary politics:

It is useful to consider the article quoted above when looking at the nature of the debate and the partisan bitterness that is often at the heart of the public discourse regarding Lewis’ legacy as a figure. The question of his antisemitism and wider historical questions regarding his alleged fascism and political ideology are often confused. The publication of Jones’ book, which was a thorough academic assessment of the accusation of fascism against Plaid Cymru – and Tim Williams’ comments on the subject – led to a not insignificant public row, and it is worthwhile for those who are interested to read the articles and the comments posted below them in order to get a better idea of how this fraught topic is influenced by different political, cultural, academic and personal alignments.

Perhaps it is inevitable that the discussion of Saunders Lewis’ antisemitism, and the wider debates about his political ideology, are inexorably tied to the political persuasions of those taking part in that debate. The conversation regarding the validity or not of Saunders Lewis as a figure, and how he should be interpreted, become an extension of these contributors’ views regarding topics such as the true nature of the history of Wales, the cultural fate of the nation, its constitutional future, the importance of the language to its formation as an entity and all kinds of similar gargantuan, unruly and knotty questions.

Grahame Davies’ summary of the public discussion is as good and balanced as any could draft, so I shall quote his words here:

In an age where memorials, statues and notices for public figures are the subjects of continuing discussion as well as of political debate and campaigning, it is worthwhile our reflecting and considering as Welsh people our understanding of these questions and considerations, while attempting to evaluate our national figures. By continuing to face difficult questions and creating new ways of discussing and understanding our history and culture which are more meaningful and gentle, would we not better understand not only the person behind the icon, but also our own comprehension and ownership of our national history? This must be done out of respect for the minorities that are among us and part of us.

Our understanding is not like iron or bronze, it is clay yet to be fired – being shaped and reworked continuously. This is another thumbprint on that conversation – and perhaps it will motivate others to respond again. It is a duty on us all to mould our history collectively: it is a statue with no final form.

Bibliography

- Davies, Grahame. ed. (1997) ‘Rhagfur a Rhagfarn’. Taliesin 100. Gaeaf. pp. 61-77.

- Davies, Grahame. gol. (2002) The Chosen People: Wales & the Jews. Penybont: Seren.

- Evans, Meredydd. (1989) ‘Gwrth-Semitiaeth Saunders Lewis’. Taliesin 68. Tachwedd. pp.33-45.

- Edwards, Marc. (2024) ‘Saunders Lewis, Powys Evans a’r asgell dde adweithiol’. O’r Pedwar Gwynt. Gwanwyn. pp.3-8.

- Jones, Dafydd Glyn. (1989) ‘Dwy Olwg ar Saunders Lewis’. Taliesin 66. Mawrth. pp. 16-26.

- Lewis, Saunders. (1933) ‘Propaganda’r Papurau Saesneg’. Y Ddraig Goch Cyf. 7, Rhif 6. Mehefin. pp.1-2.

- Lewis, Saunders. (1941) Byd a Betws. Aberystwyth: Gwasg Aberystwyth.

- Lewis, Saunders. (1993) Selected Poems. Caerdydd: University of Wales Press.

- Williams, Tim. (2014) ‘Know a hero by his heroes: Saunders Lewis beyond apologetics’ Available: https://www.iwa.wales/agenda/2014/09/know-a-hero-by-his-heroes-saunders-lewis-beyond-apologetics/ [Retrieved: 9 May 2025]

EASTWOOD, Paul, Saunders Lewis © Paul Eastwood, Photography by Rhian Israel