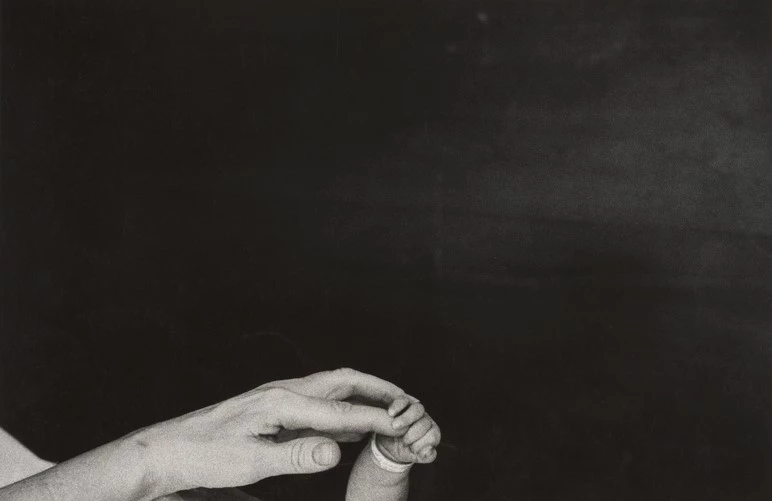

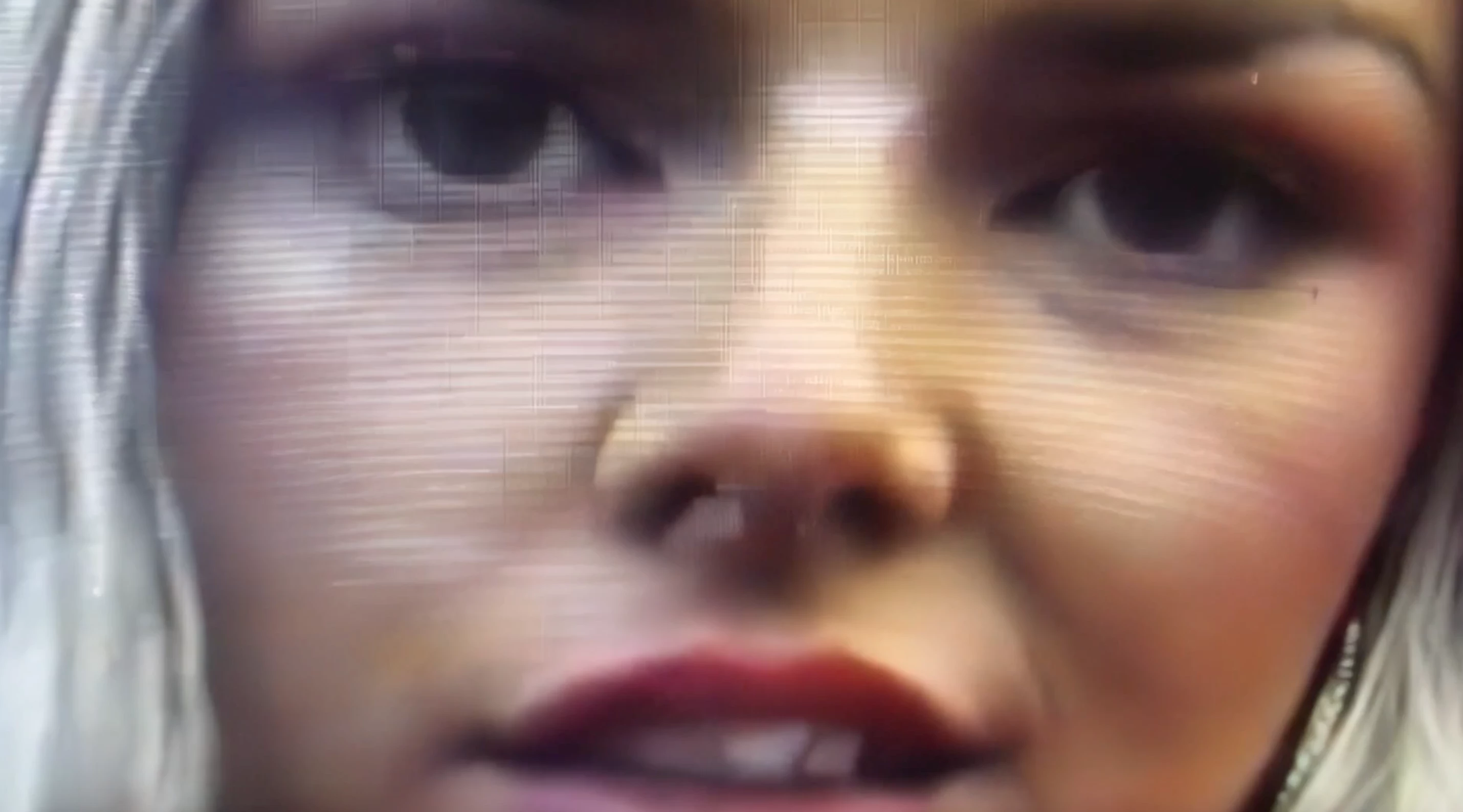

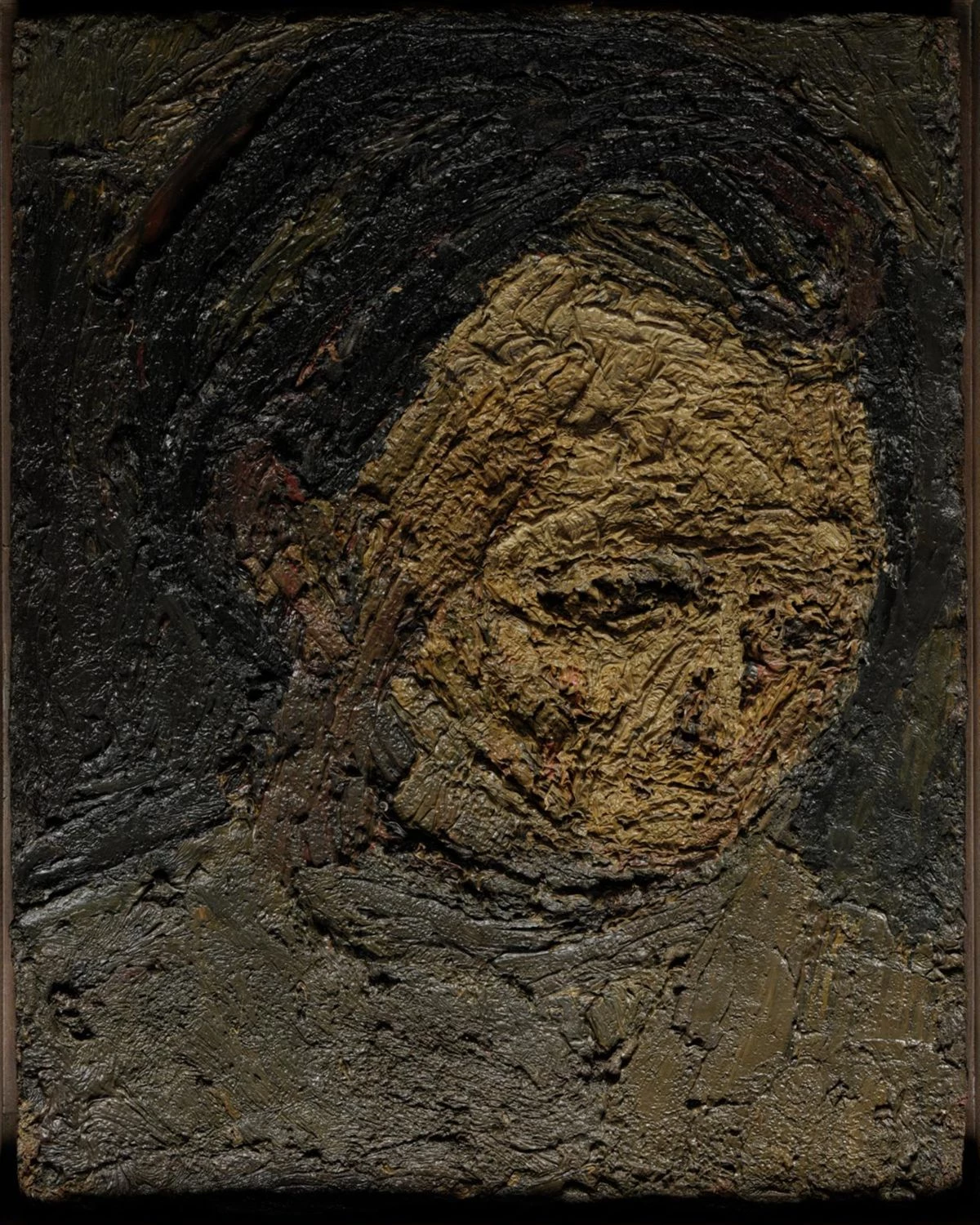

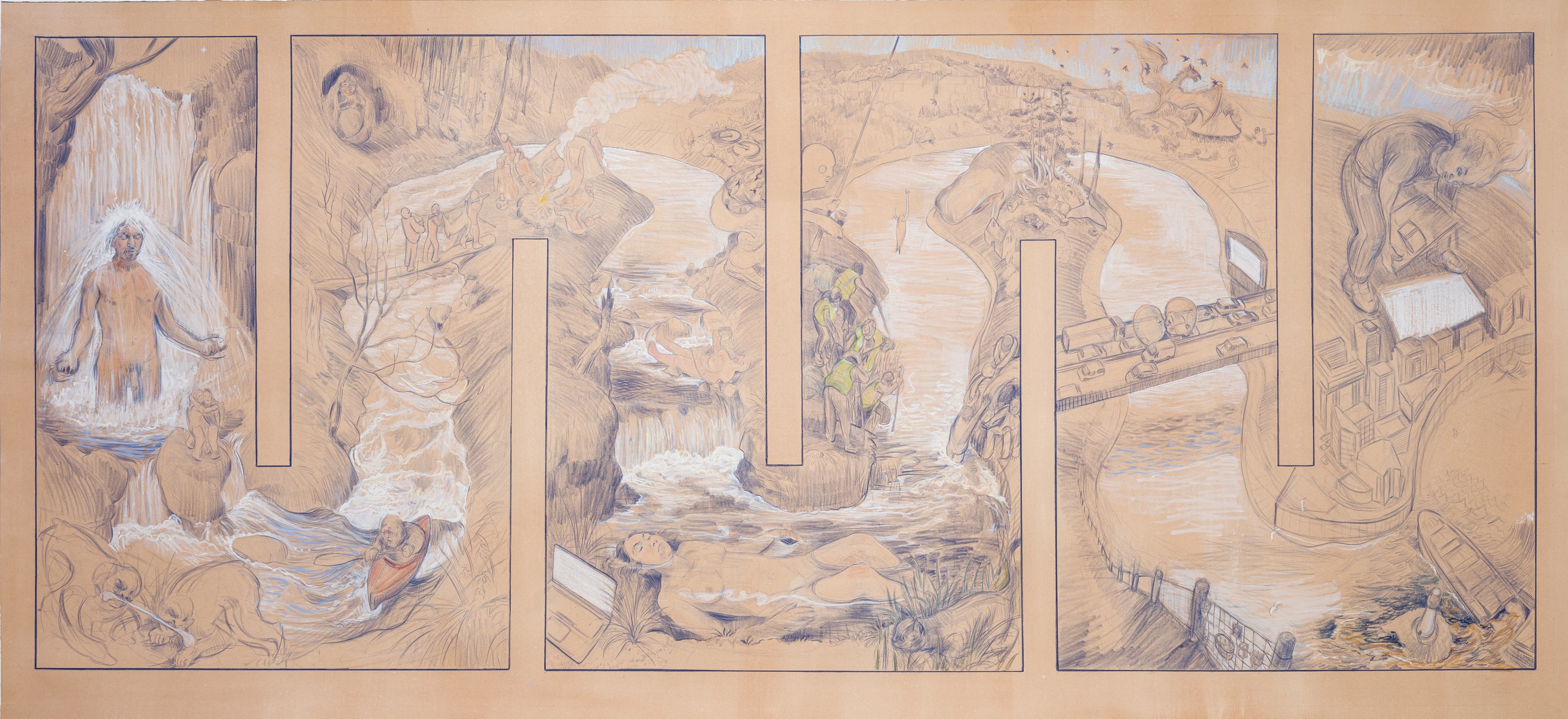

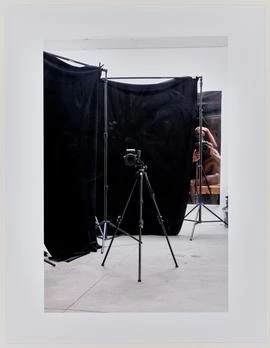

Reflections on a photograph by Chloe Dewe Mathews from her series Caspian: The Elements

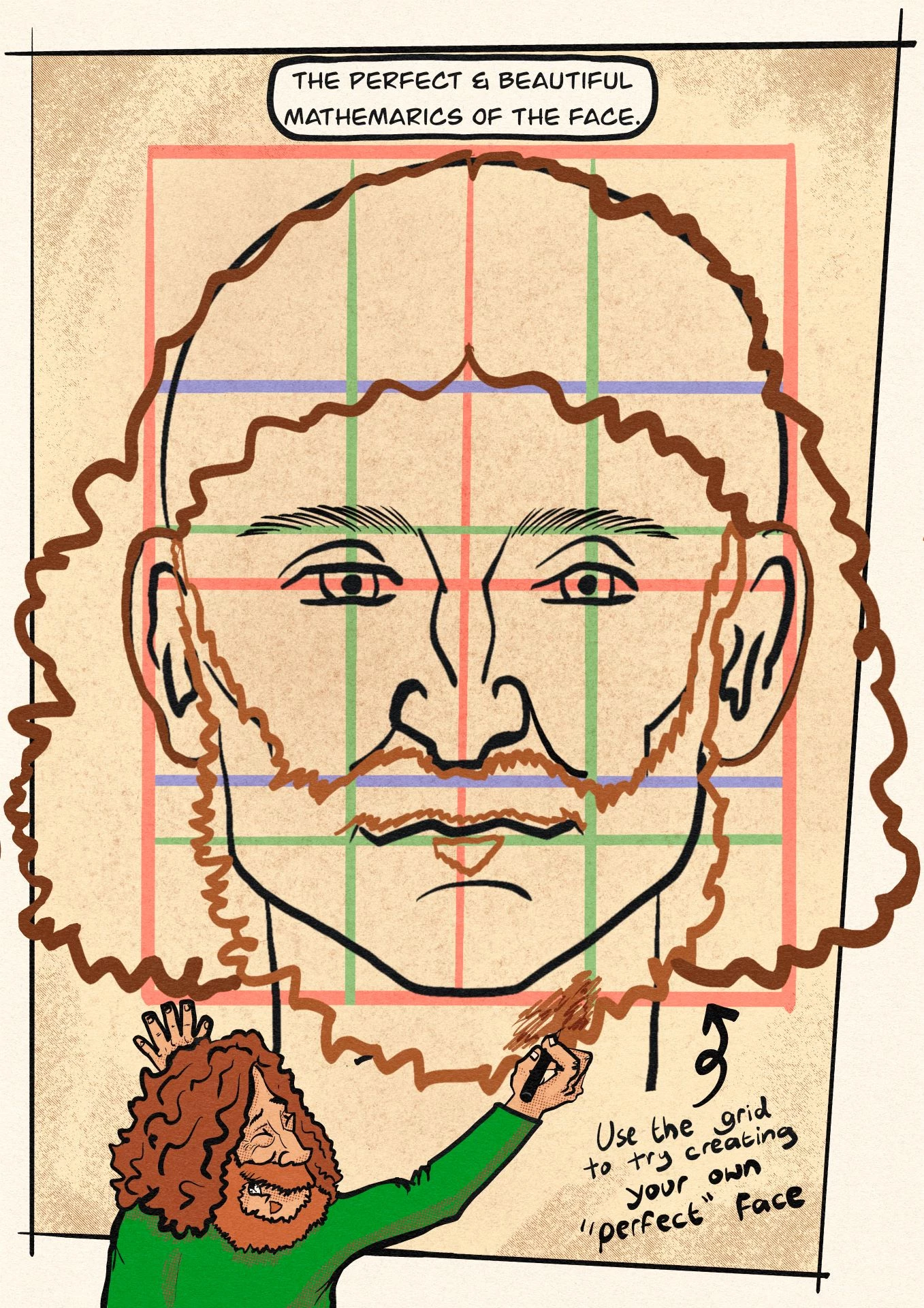

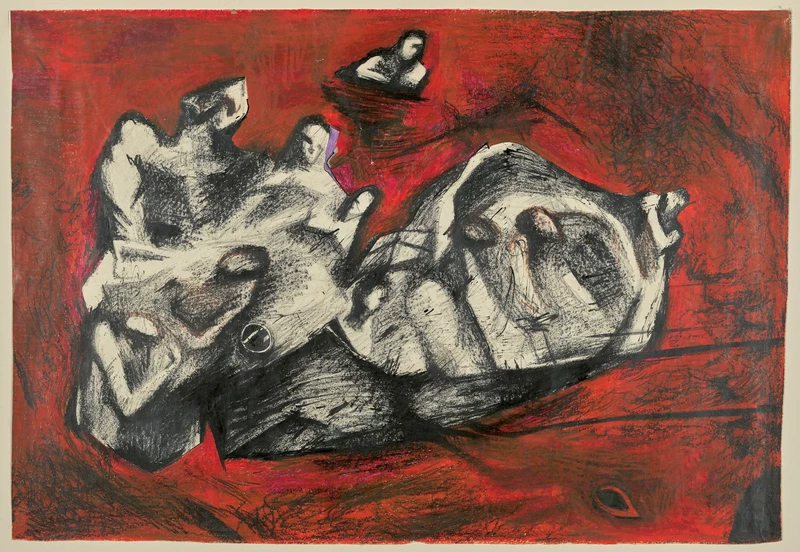

Her nudity is chaste. A thick blackness covers her bust like a dress. Her face seems numb. Her eyes, fixed on a distant point, are void of any emotions, as if void of consciousness. Not even a trace of hope can suggest why she is sitting in a mess, in a bathtub filled with what looks —and probably smells—like used engine oil. It is crude oil, hydrocarbon, fossil fuel … and naft in my mother tongue. It really is naft!

‘Wellness’ wouldn’t occur to me as a reason. Rather illusion. Delusion. Isn’t she withstanding nausea? Never mind cancer.

The beads of gold don’t really adorn her neck. They only complete the absurdity of the scene by contrasting the ‘black gold’ against real gold, reminding me that both elements rule the world, more often as a curse than as a blessing. Symbols of power and money.

(The eyes that captured this image for the world were as intrigued as mine)

The woman is from around the Caspian. From one of the countries surrounding the tormented sea which is the largest salt lake on Earth. But could she be from Iran; my lost homeland?

Since I left many decades ago, women have been forced to cover themselves head to toe in fabric, even in photographs. But this woman is nude. And yet, she could be from Iran. With her black hair and her skin the colour of autumnal moon, like my grandmother’s, made from the same soil, the same salt … Yes, she could be from my family. The entire territory surrounding the Caspian was once Iran, ruled by a just empire, or so we wish to think.

***

The Iranian coast of the Caspian was the setting of my holidays when I was a child. We would pack for the three summer months, load all we could in and on top of three or four cars and drive north from Tehran. On the dangerous serpentine Chalus road, through its long dark tunnels, giant holes cut through the heart of the Alborz mountains, we would reach the Caspian. During the five-hour journey, we would sing and laugh all the time. On every journey I would feel excitement rise in me long before the Caspian appeared in the distance. I could sense it, as if the sky opened up right there. This old image reappears perpetually, awakened by the Irish Sea each time I walk down to the beach of Aberystwyth in Mid-Wales. All seas are members of one family. They all sing in their hearts. The Caspian was once mine in full.

We would spend the entire summer on the beach of the Caspian, eat sturgeon and corn cobs grilled on charcoal. It was here that I learned to swim. We would make new friends. I had my very first crush on a grownup who looked like Elvis.

And sorrow was something unknown.

It’s all gone now. None of it is left to the generations that came after me. Sturgeon is ‘haram’ now; bath suits forbidden. Who would have thought? Not even the grownups could have imagined it would come to this!

‘Wellness’ wasn’t a word used to sell things that people don’t need. Never mind cancer! We were ‘well’ in those days because we lived. Each of us a well of joy. Who would have thought that people would one day take to bathing in black crude oil in a tub?

It was long before women were forced to cover themselves from head to toe in fabric. If at all, they are now only allowed to bathe in that coverage. I’ve even heard of walls built in the Caspian to separate women from men lest they could desire each other’s flesh.

It was before religion dictated that men are dangerous to women who are not covered in fabric from head to toe.

It was long before the laws and the oil became poison to the Caspian and the curse came upon its flora and fauna.

In those days, grownups used to say that oil is poison. Naft, in Persian, is the blackish greasy reeking liquid. True, it would give us warmth during ice-cold winter months, when Grandma would fill with it her old blue Valor heater. Then the smell would be very weak and almost pleasant. But if a drop of it fell on my hand, she would shout go and wash your hands immediately or I must call the doctor. You’ll get blind if you rub your eyes, girl!

It was long before naft would be spilled in the Caspian and form black slicks on the surface of the blue water. And birds would migrate for ever when they saw their dead float on the surface of the Caspian. And the protectors of Mother Nature would be brutally punished for raising the alarm.

It was long before people would, of their own free will, sit in a black mess, in deadly silence, deluded into believing that what is expensive is good and healthy, no matter how dirty and reeking, like the woman in a photograph, which turns her into a symbol of protest.

For millions of years the Caspian had hidden the black curse in her depths under thick crusts of earth. Long before shallow bathtubs were invented. Long before words were invented, and poets could chart the course from those ancient tallow lamps in the heart of night’s blackness to the smoke rising from oil towers to blacken the day’s light.

Shara Atashi is an award-winning author and translator based in Aberystwyth, Wales. She is the daughter of the Iranian poet Manuchehr Atashi. In 1979, at the age of twelve, Shara and her mother migrated to Germany, where she completed her school education and later graduated in law. She relocated to London in 2012, and later moved to Wales to focus on her writing. In 2021 she was awarded a ‘Representing Wales’ writer. Her work has been published in numerous literary journals, mostly in Writers Mosaic, New Welsh Review, Planet, Nation Cymru. Shara was awarded ‘Highly Commended’ in the Stephen Spender Prize 2022. More information about Shara and her work can be found on the Writers Mosaic website.