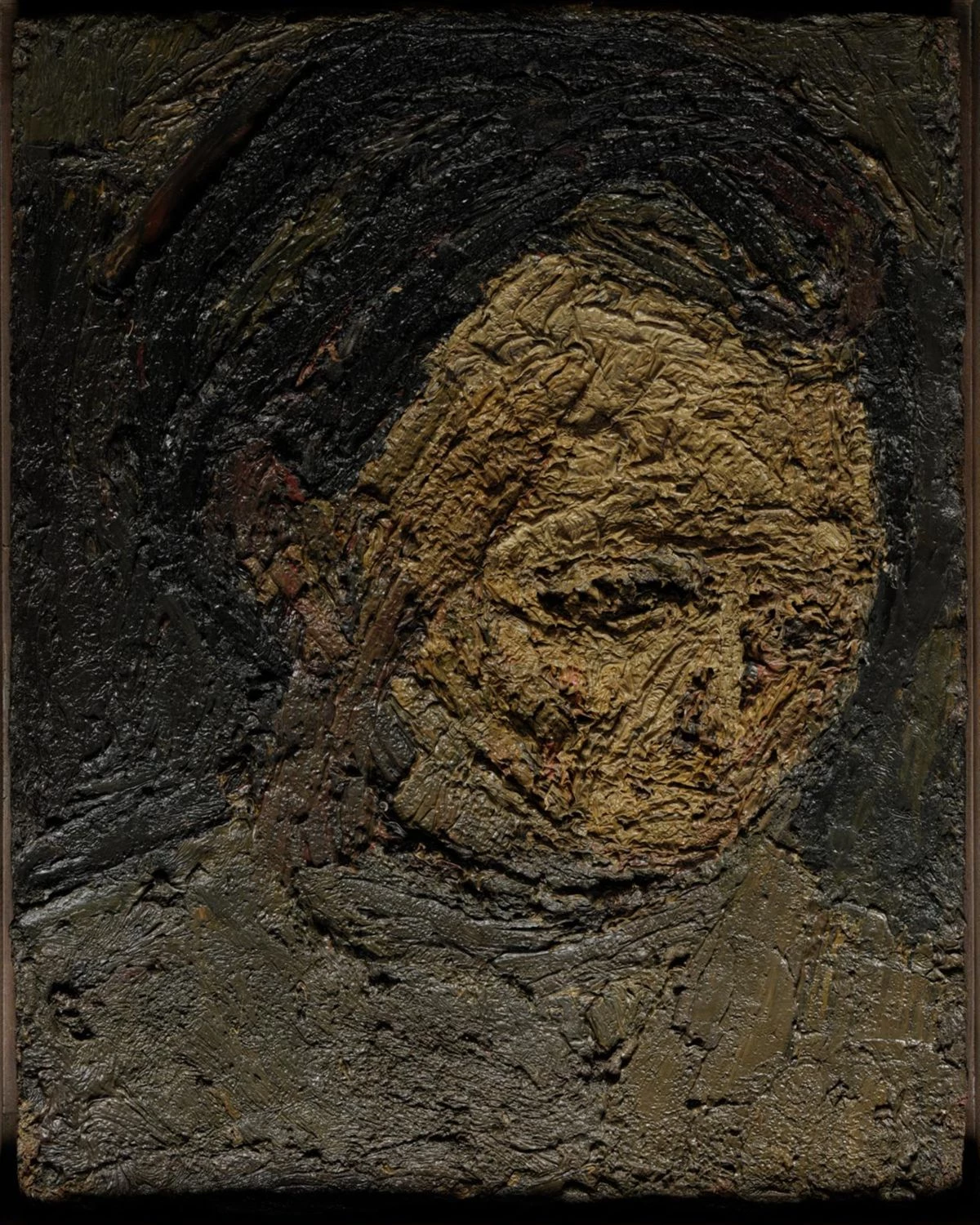

Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales recently acquired 7 paintings by the Welsh painter George Poole (1915 – 2000) that were painted during the 1940-60s. I saw these paintings for the first time in the painting conservation studio where they had arrived for treatment. As first impressions go, I was fairly underwhelmed. They were all dirty, many of them with scratches and paint losses, and at first glance I didn’t think their appearance would improve much.

However, paintings have a habit of surprising you, and I have to say I’ve been won over by this group of paintings. One of the best things about my job is being able to spend so much time in front of artworks, and this almost always improves your appreciation of them. Even relatively subtle shifts in colour and gloss can make a massive difference to the way a painting looks. I have often noticed how even small paint losses and scrapes can distract from the impression intended – we can see the neglect, and it has a strong impact on how we interact with a work.

In this case, several of these paintings presented me with interesting challenges. The variety of surfaces and painting technique across the group kept me on my toes as each painting needed a slightly different approach.

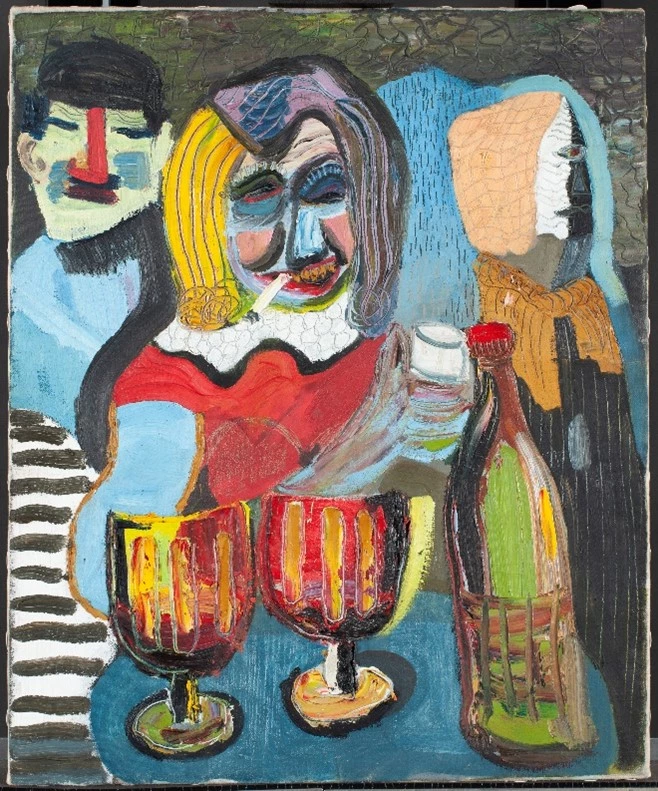

The Two Policemen

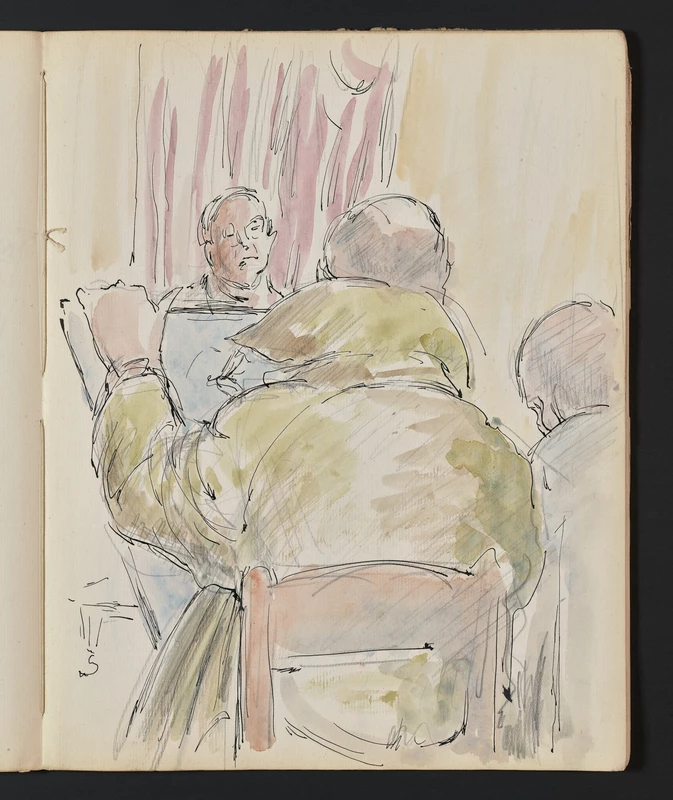

I was initially very confused about the Two Policemen. Confused about what was going on in the scene depicted, and also what was happening on the surface of the painting. While I still don’t know what the policemen are conspiring about, I did make progress with the painting.

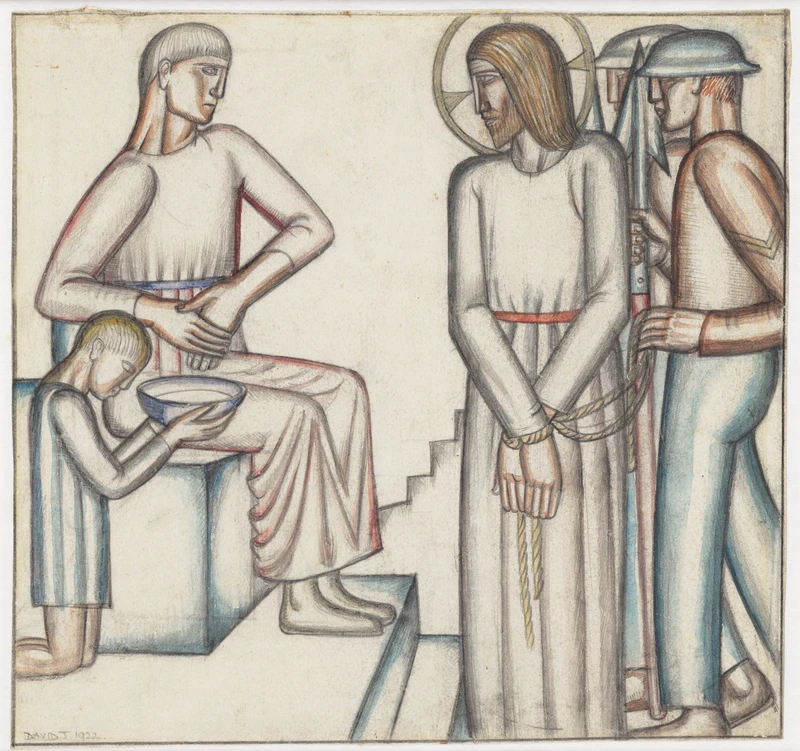

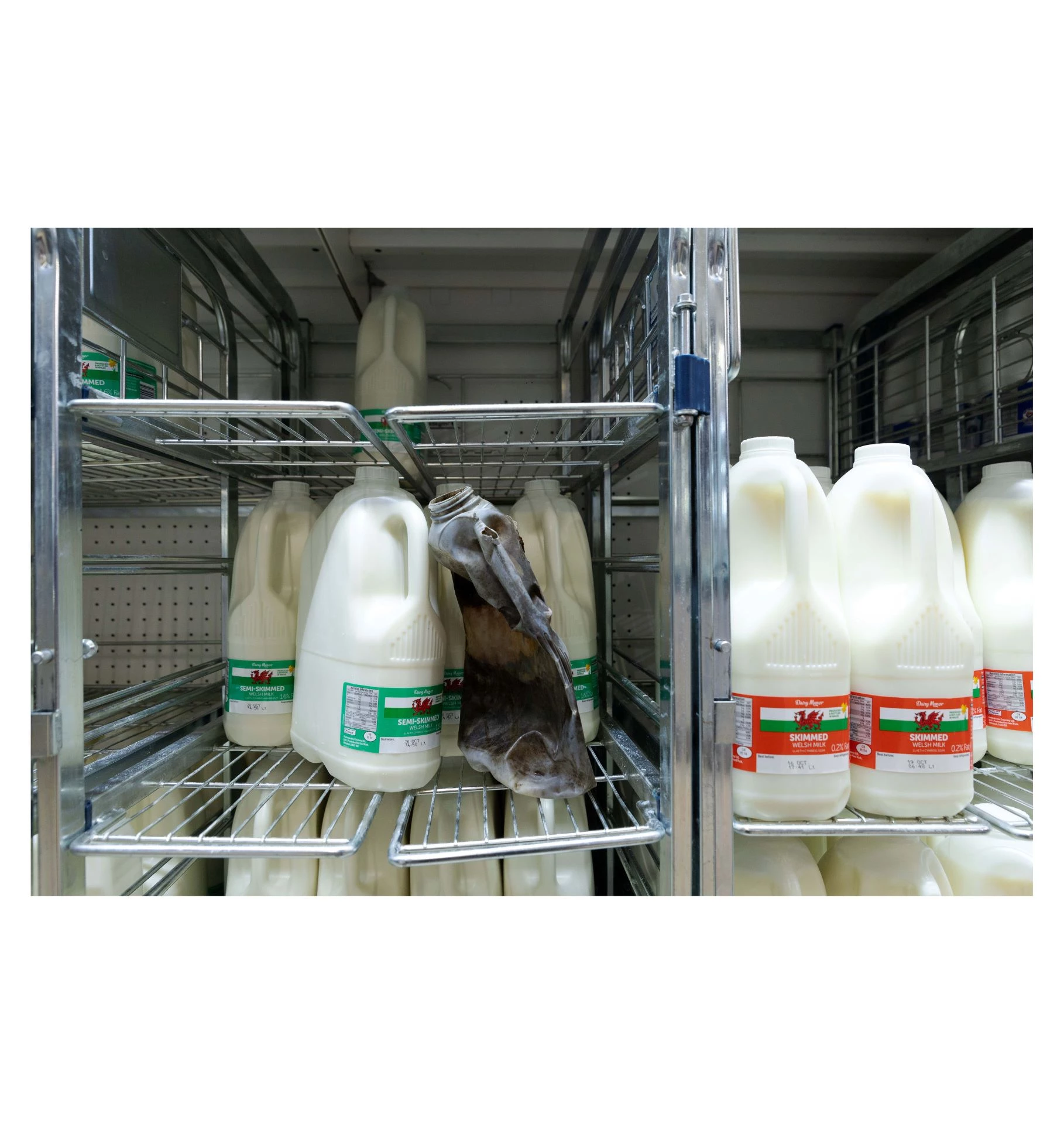

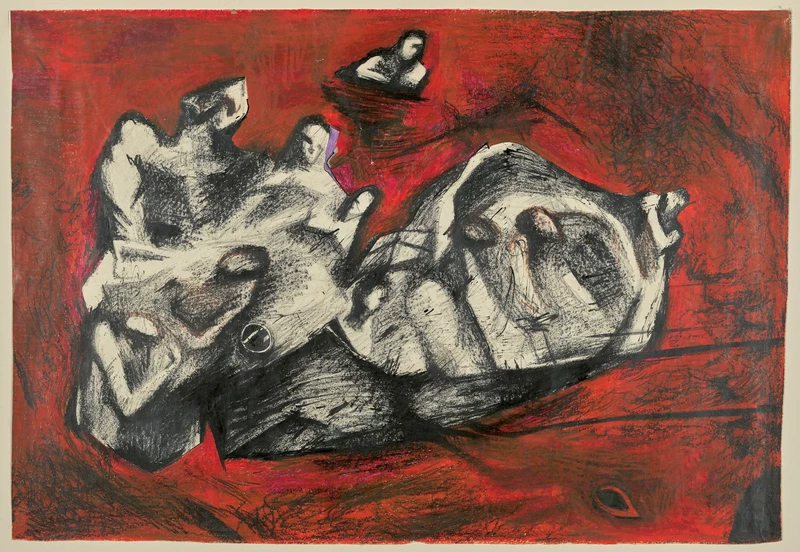

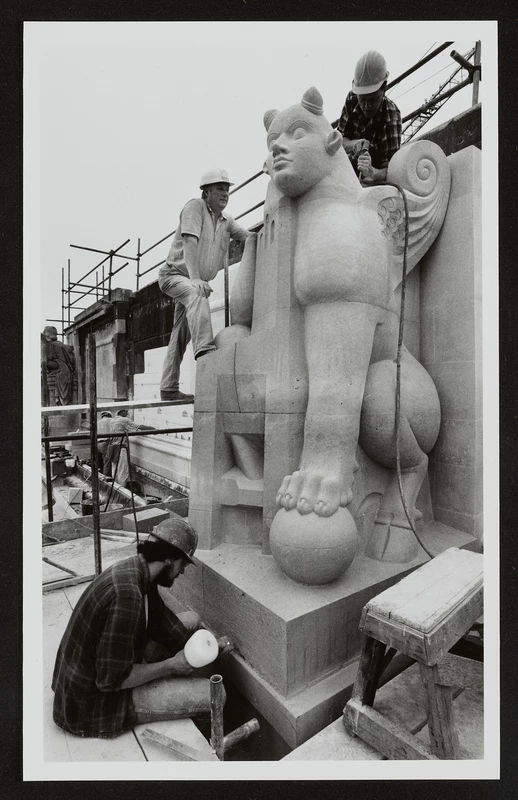

POOLE, George, Two Policemen © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [before conservation treatment]

POOLE, George, Two Policemen © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [after conservation treatment]

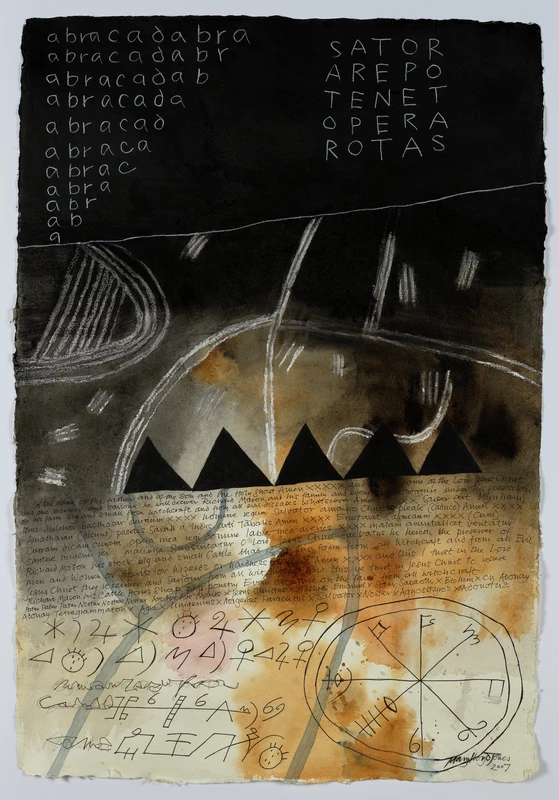

The painting was dirty and had splatters of green paint across the surface. There were several areas of paint loss and scratches in the top paint layers and areas where the surface had a white, cloudy appearance.

Once the dirt was removed, it became clear that Poole had applied wax to the surface of the painting and had then painted over the wax in certain areas, for example the houses and the blue uniform of the policeman. The cloudy white areas were where the wax had become opaque. In the top two corners the wax was absent and the paint was worn, suggesting that these areas were damaged and the wax had been scraped away in that process. The absence of wax in those areas made the sky look lighter and more matt as the wax saturated the paint elsewhere.

POOLE, George, Two Policemen © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [during surface cleaning]

I’d never come across an artist who used wax as a surface coating to saturate and change the gloss of their oil paintings before, and I needed to think carefully about what to do about the corners. The visual evidence suggested that there used to be wax in the corners. I wanted to correct that visual disturbance of the missing wax, as it created an uneven and distracting visual effect in the sky. But if I applied wax, I would not be able to remove it without affecting the original wax coating.

An important tenant of conservation is reversibility. This particularly applies to things like varnishing and retouching paintings, as varnishes and restoration can discolour over time and need to be removed and reapplied.

After some thinking, the missing wax was replaced with an acrylic varnish that would give a similar saturation and gloss to the paint, whilst having a different solubility to the wax so it could be removed in the future if needed. The opaque areas of wax were reformed with gentle heat and some buffing, and the paint losses were retouched with watercolours.

POOLE, George, Two Policemen © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [during conservation treatment]

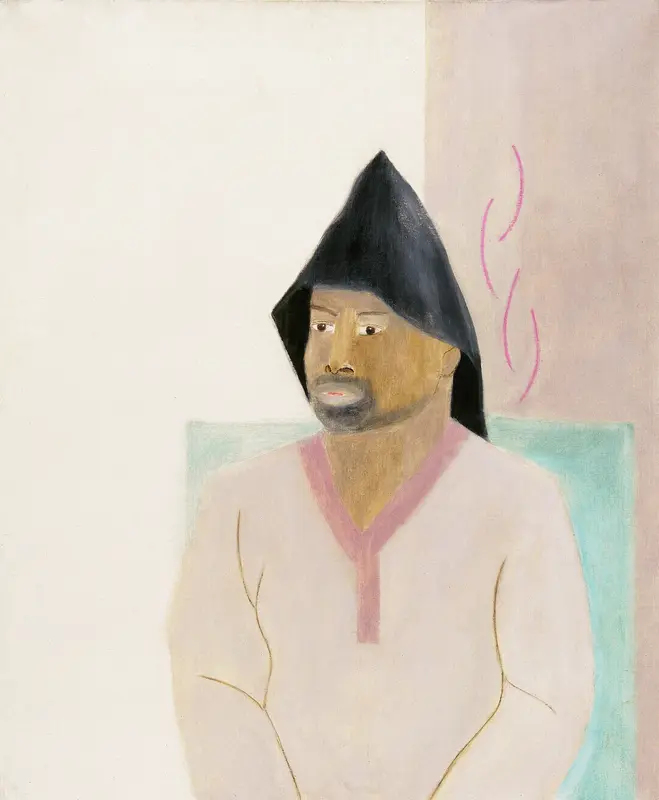

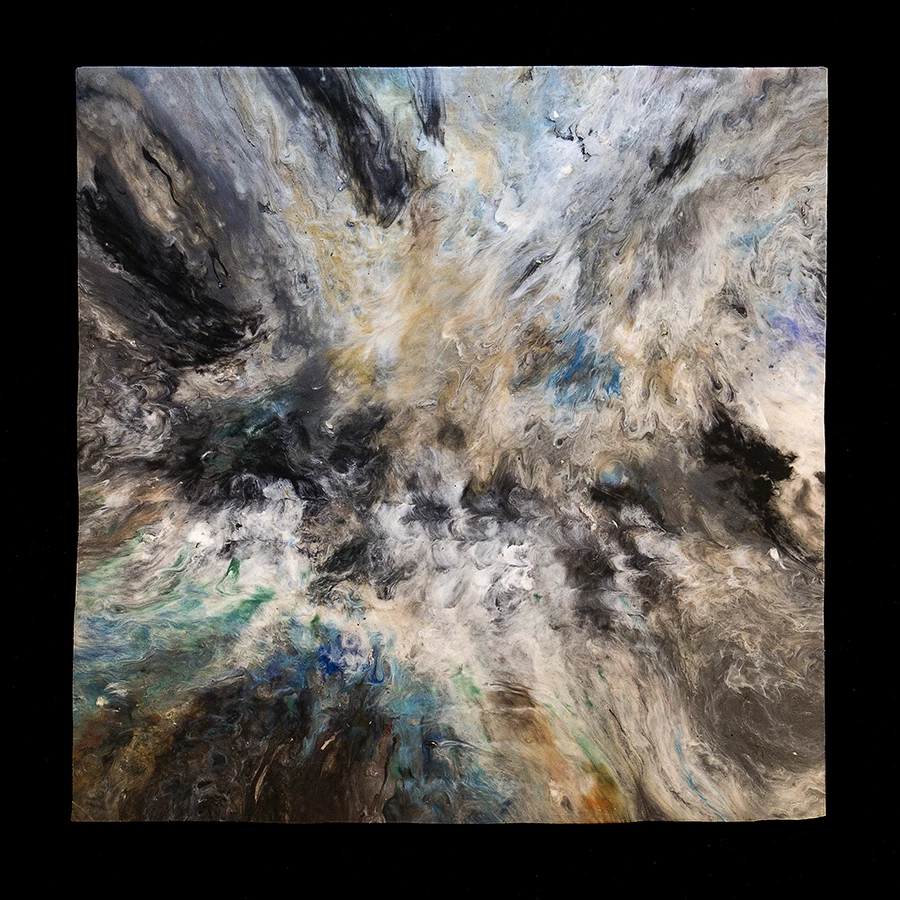

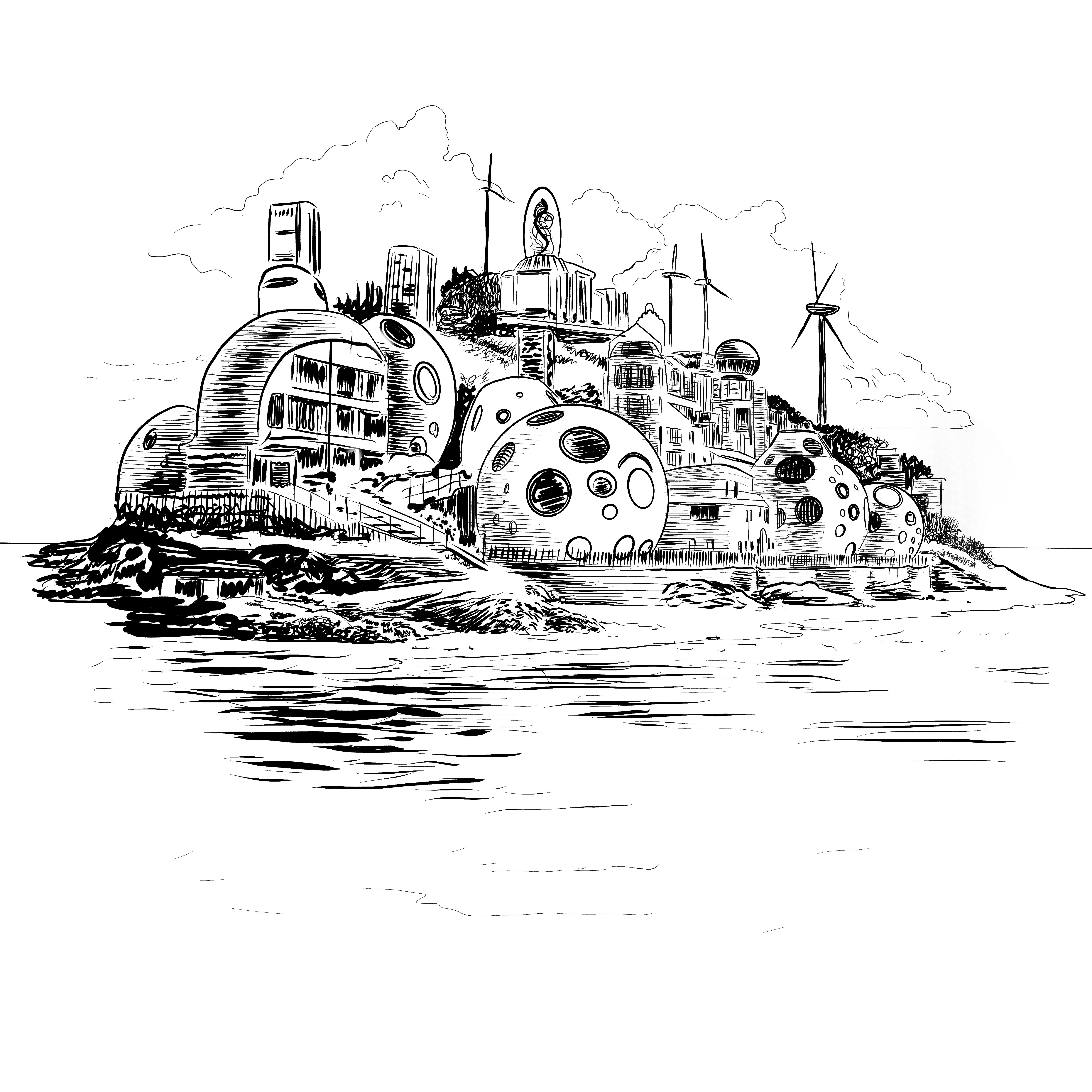

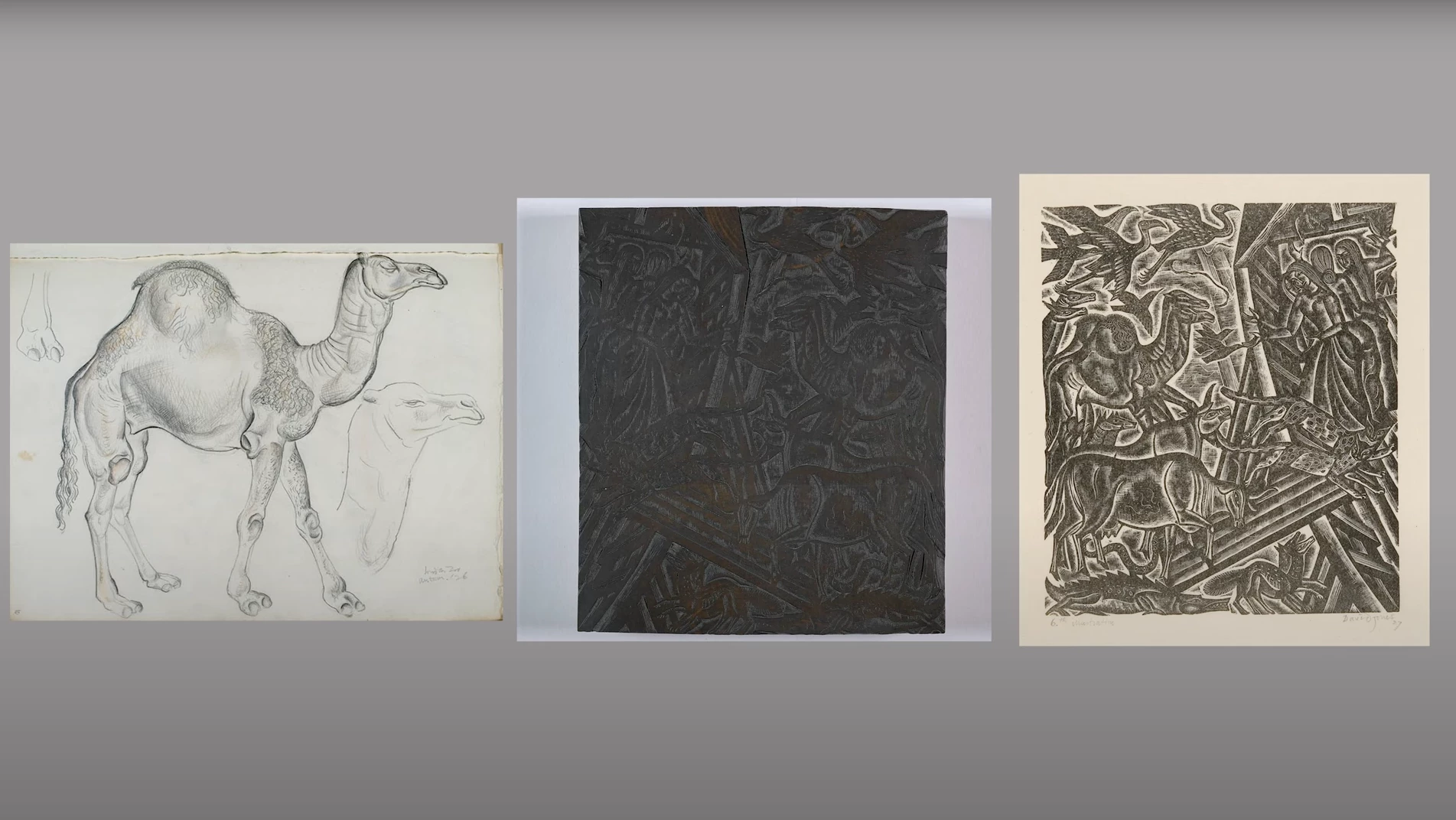

Untitled or Woman Smoking with Wine

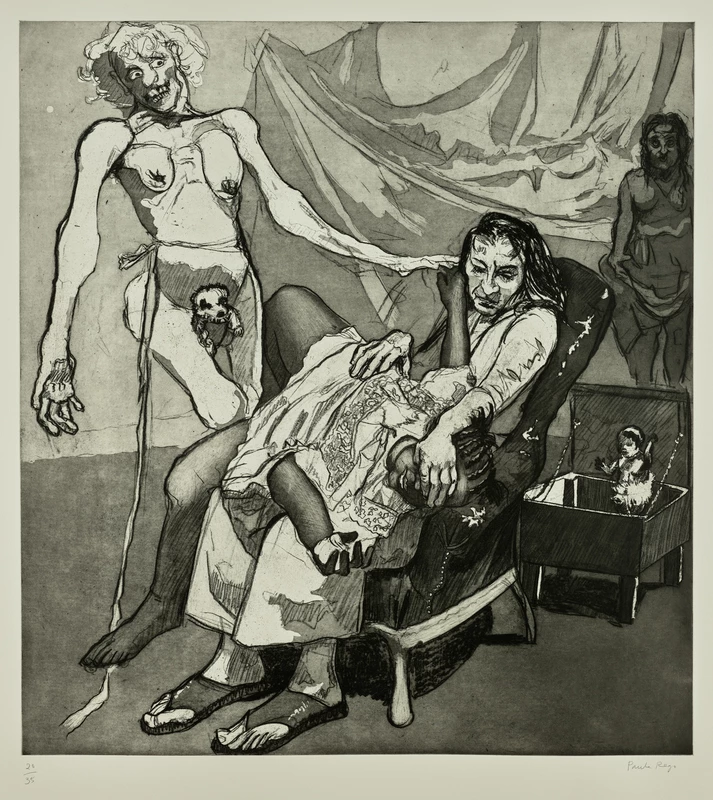

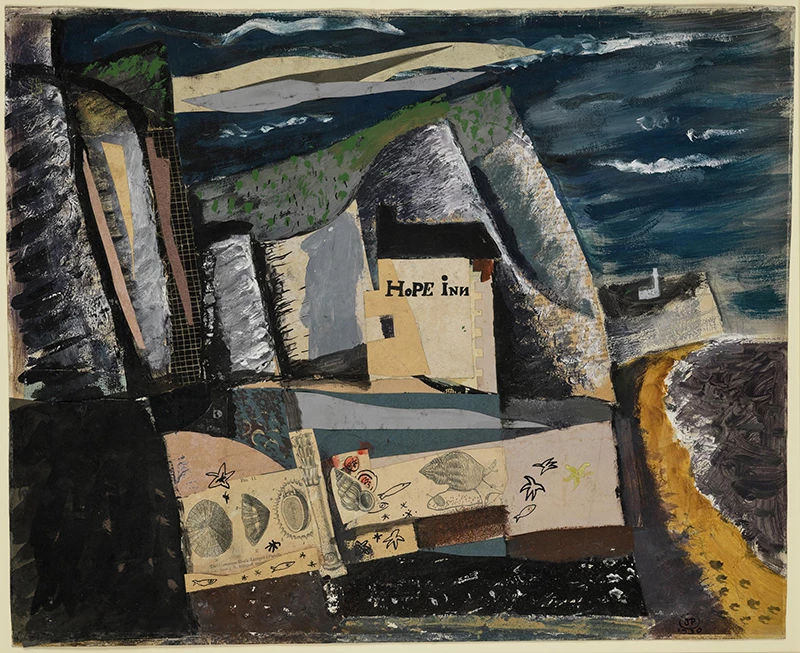

I liked Woman Smoking with Wine as soon as I saw her, but the paint was particularly unstable. It already had lots of paint losses and more areas of raised flaking paint getting ready to fall off and be lost forever. It had also been stretched onto a very shabby, non-original stretcher that was too small. This was causing the paint to crack along the top and bottom edges.

Firstly, the flaking paint was consolidated and stuck back down onto the canvas. The painting was then surface cleaned, removed from the stretcher and the edges flattened. A new stretcher was ordered and a loose lining was stretched up to support the original canvas. The painting was then re-stretched.

The high impasto of the paint was challenging to reconstruct with a reversible white fill material, but I had a great time shaping the fills to continue the brushstrokes of the painting. Once the fills were in, I retouched them imitatively to restore our lady to her full glory.

POOLE, George, Untitled ('Woman Smoking with Wine') © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [details of the woman’s face: detail after consolidation and filling the losses in normal light (left); detail after consolidation and filling the losses in raking light to show the texture (middle); and detail after retouching (right)].

POOLE, George, Untitled ('Woman Smoking with Wine') © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales [after conservation treatment]

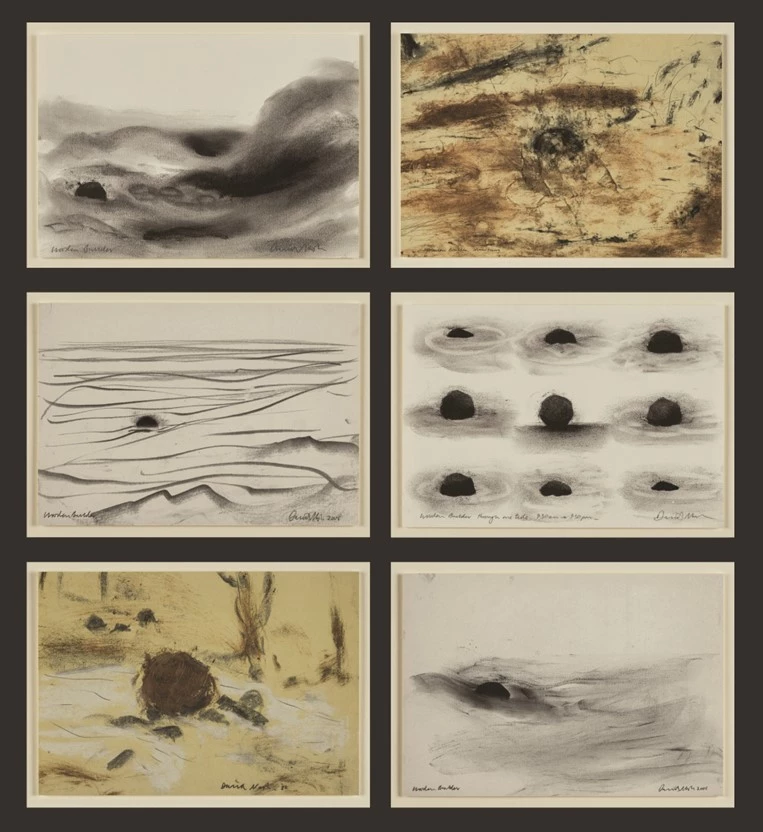

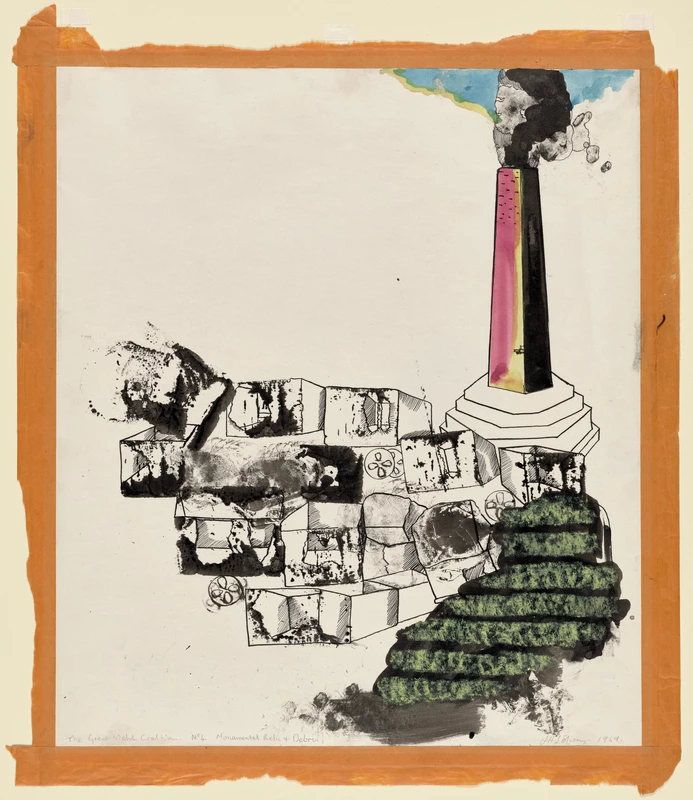

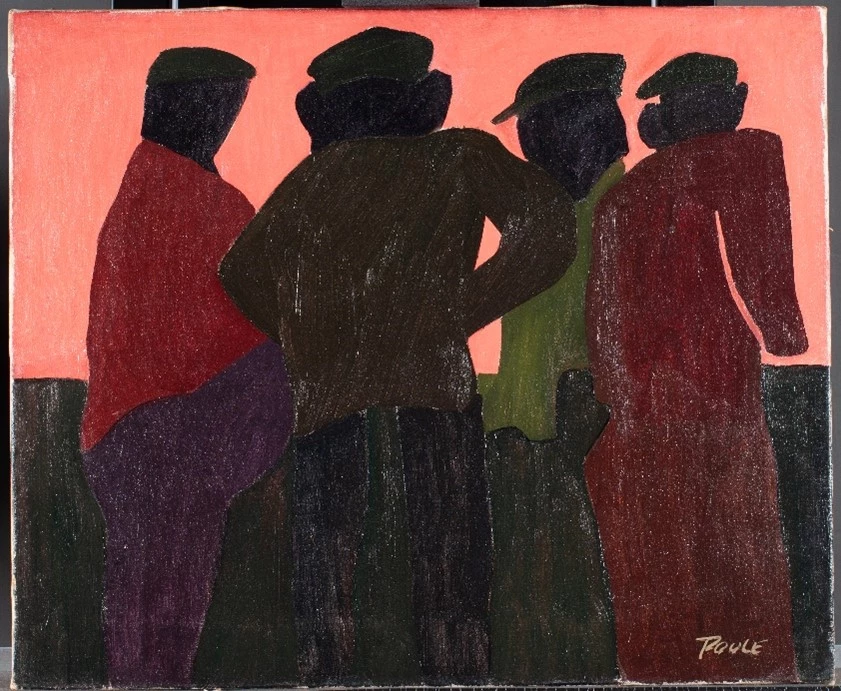

Four Miners

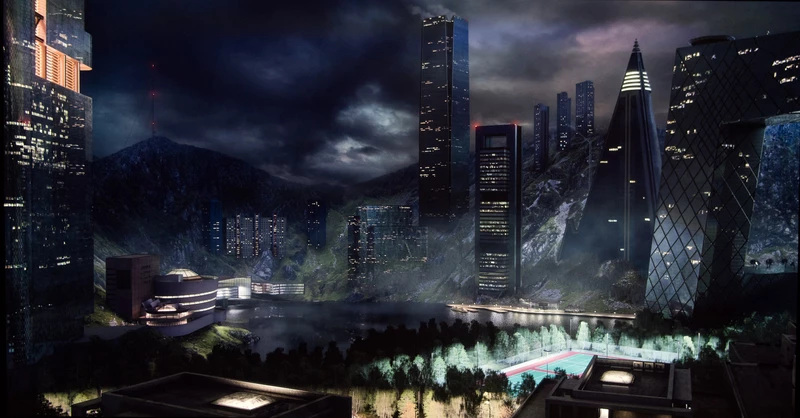

Unlike the other two paintings mentioned so far, this painting had a varnish coating on it, although the varnish was no longer saturating the painting. Surface cleaning made a good difference, but what it really needed was a new varnish to re-saturate the painting. The new varnish looked great, and then I came to retouch the small losses and I’ve never been closer to giving up and trying to find a new career.

When you’re trying to retouch losses and damages, it’s a lot easier if you can use the same pigments that the artist used. You can get to the same colour by mixing different pigments, and sometimes you have to, but on the whole conservators use their knowledge of what materials and pigments artists used to help us pick the right pigments for retouching. As I found out, it becomes a lot harder with contemporary paintings, as there are now so many different pigments available to artists. Trying to retouch this painting with my normal palette was an impossible task. I spent an embarrassing amount of time trying to retouch small losses in the hot orange/pink background. Eventually I concluded that I would need to branch out, and ordered a selection of modern, organic pigments to try. It turns out “Fluorescent Flame Red” was exactly what I needed. Unfortunately, the pigment is not completely light-fast, so it will fade over time, but it’s a small price to pay for my sanity. The retouching is reversible, so it can be redone safely in the future if necessary.

POOLE, George, Miners with Black Vest Conversation © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales [before conservation treatment]

POOLE, George, Miners with Black Vest Conversation © George Poole/Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales; [after conservation treatment]

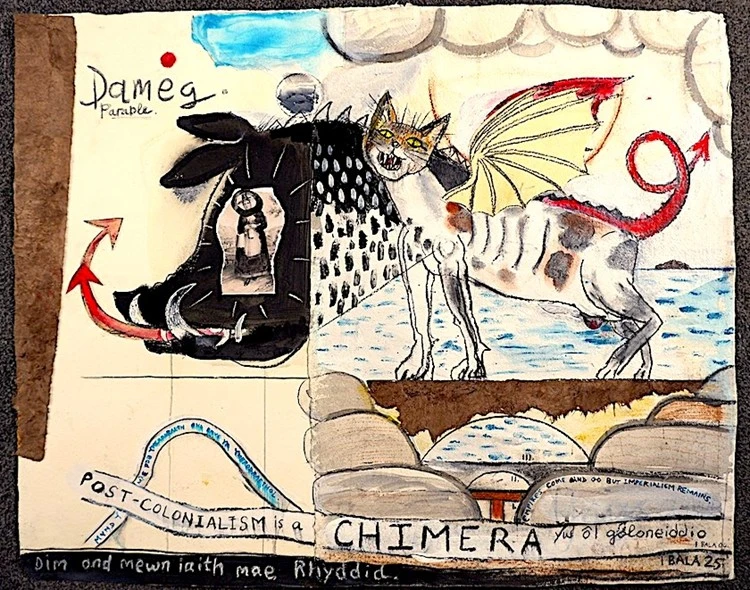

Thinking outside the box

It was very satisfying working my way through this group of paintings and a great opportunity to spend time with the work of an artist I was unfamiliar with. Modern paintings often present different challenges because artists use non-traditional materials and techniques. It’s necessary to approach modern paintings with the assumption that they will not behave like traditional oil paintings, even if they look like them. Still, part of the fun of treating these artworks is being surprised and having to think outside the box.

Three of these paintings were on display as part of The Valleys exhibition at National Museum Cardiff in 2024.

Sarah Bayliss is a Senior Paintings Conservator at Amgueddfa Cymru since 2022 and has been working in Cardiff as a freelance conservator since 2017. She studied chemistry before studying Easel Painting Conservation at the Courtauld Institute in London. Since moving to Cardiff Sarah has developed an interest in 20th century Welsh paintings and 21st century Welsh circus.