Waterfalls; Past to Present

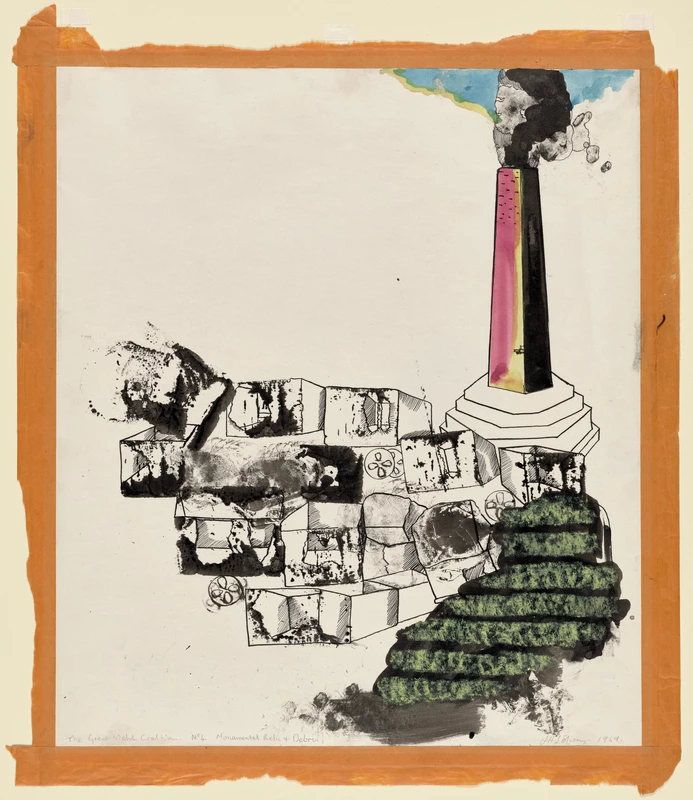

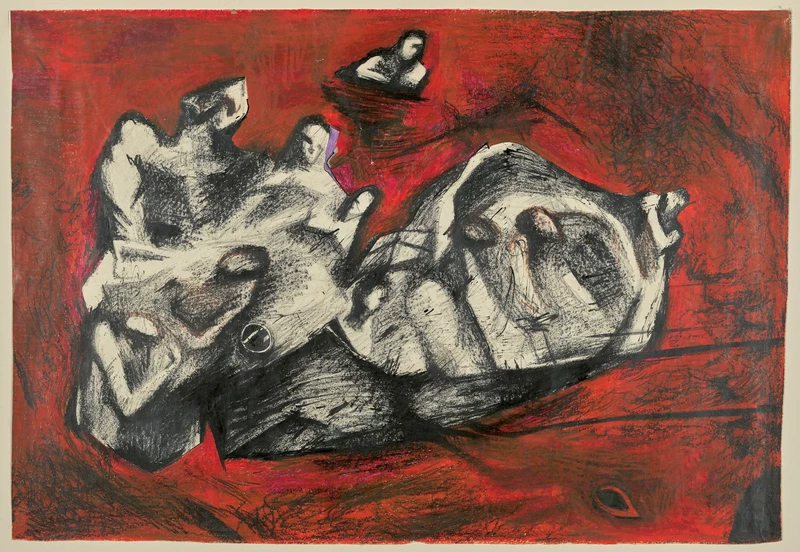

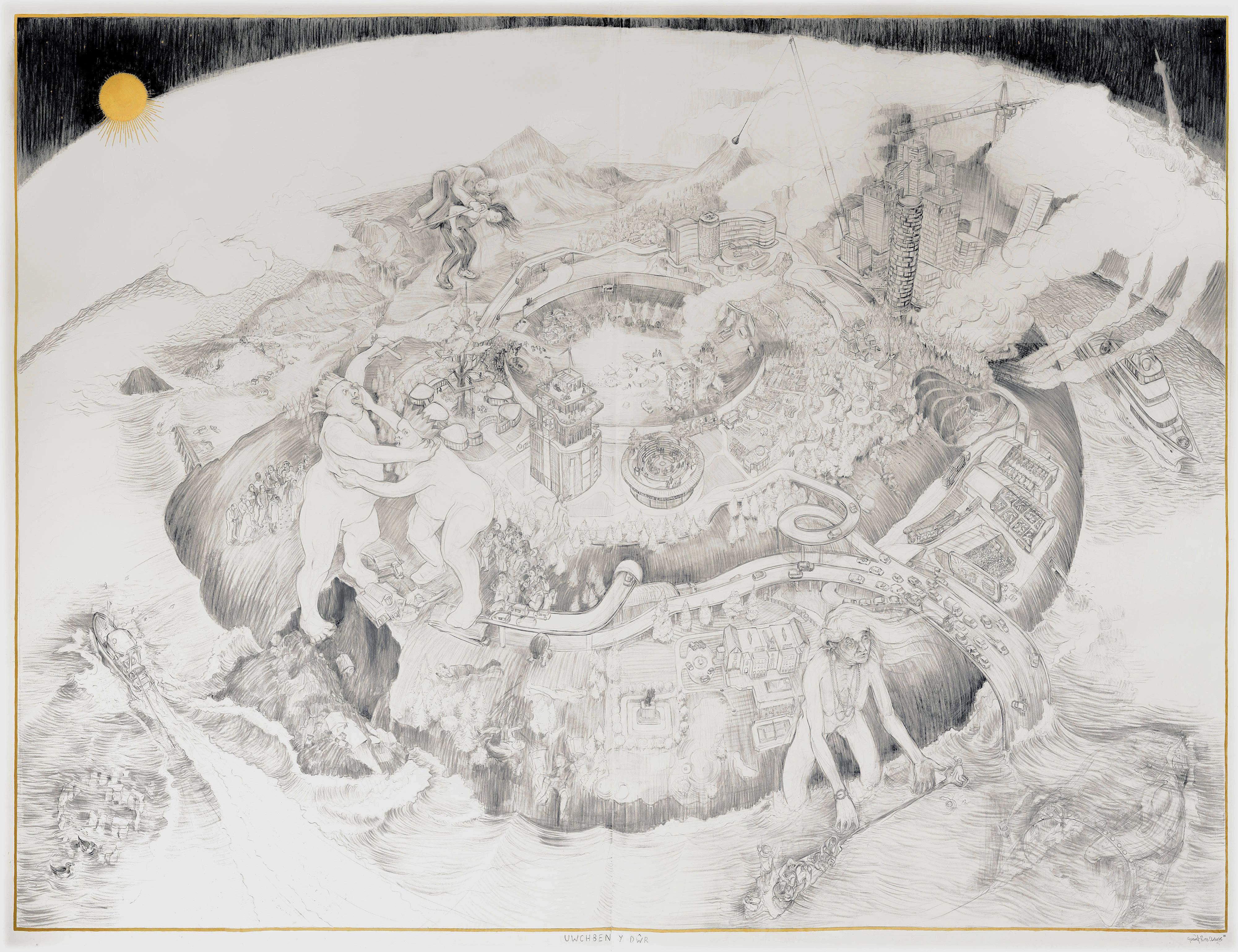

My latest work Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness) is the first exploration of an idea beginning to take form and become realised.

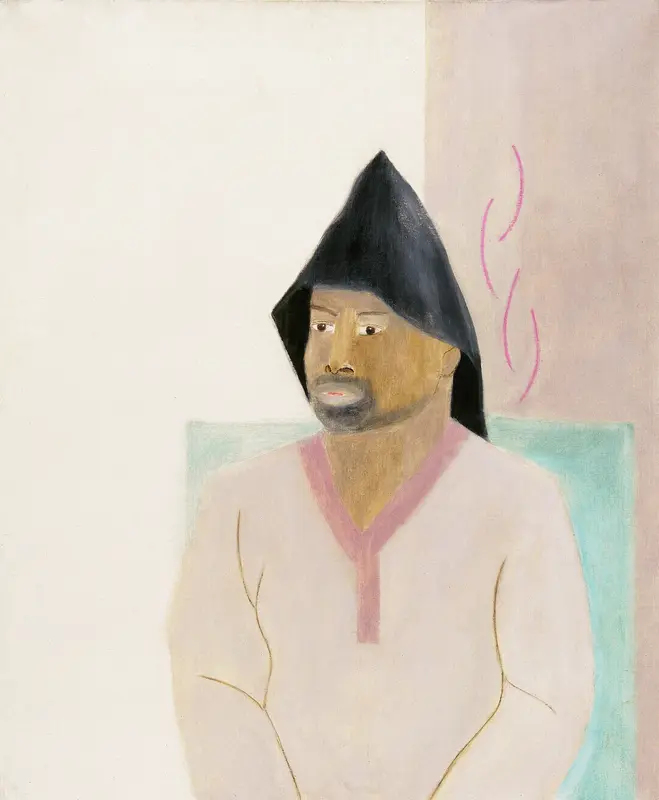

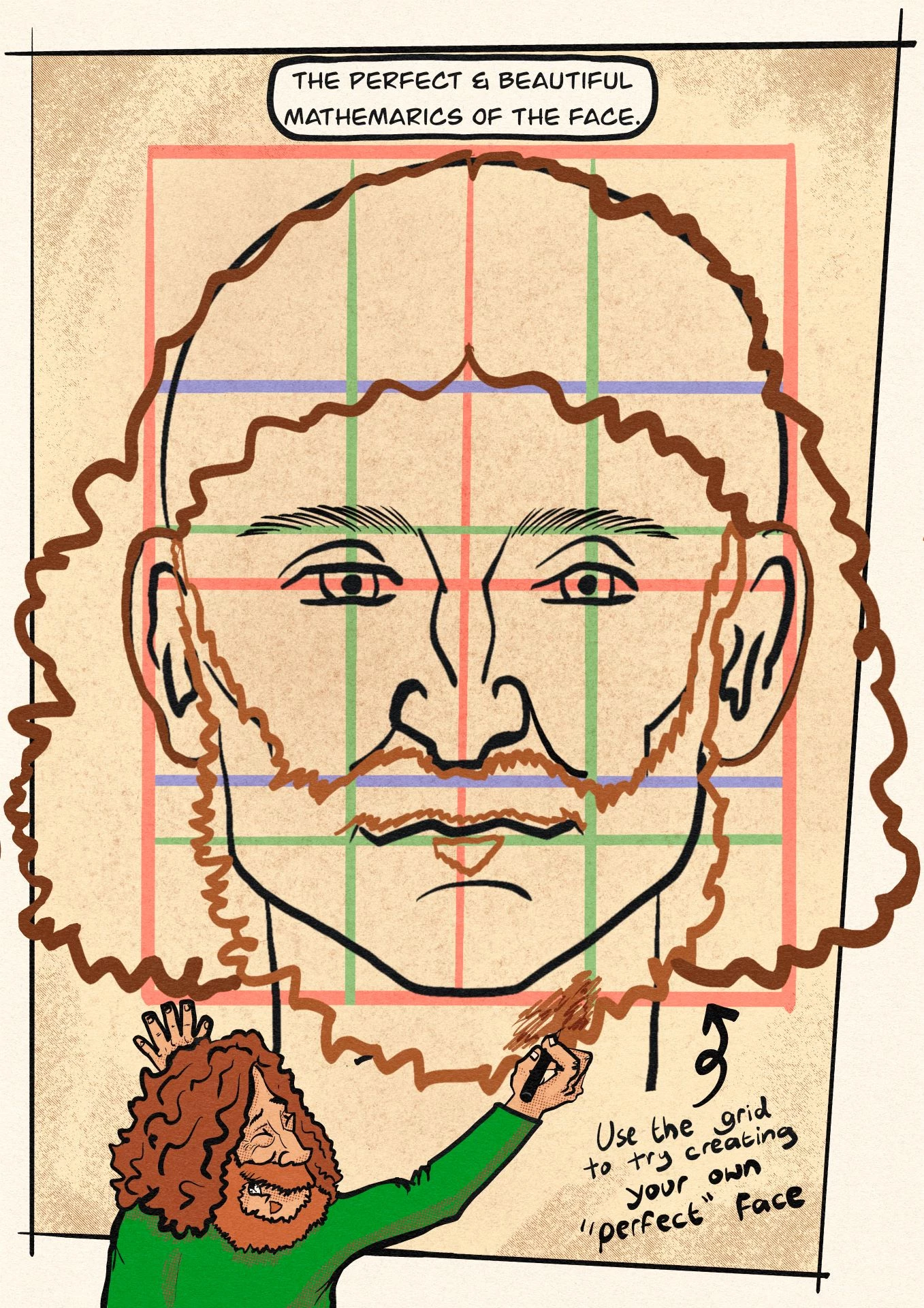

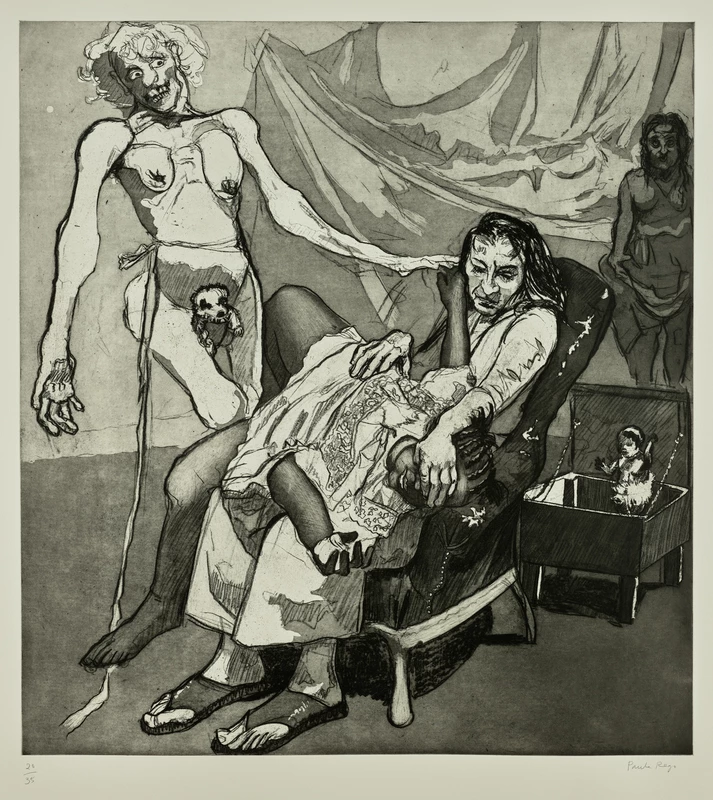

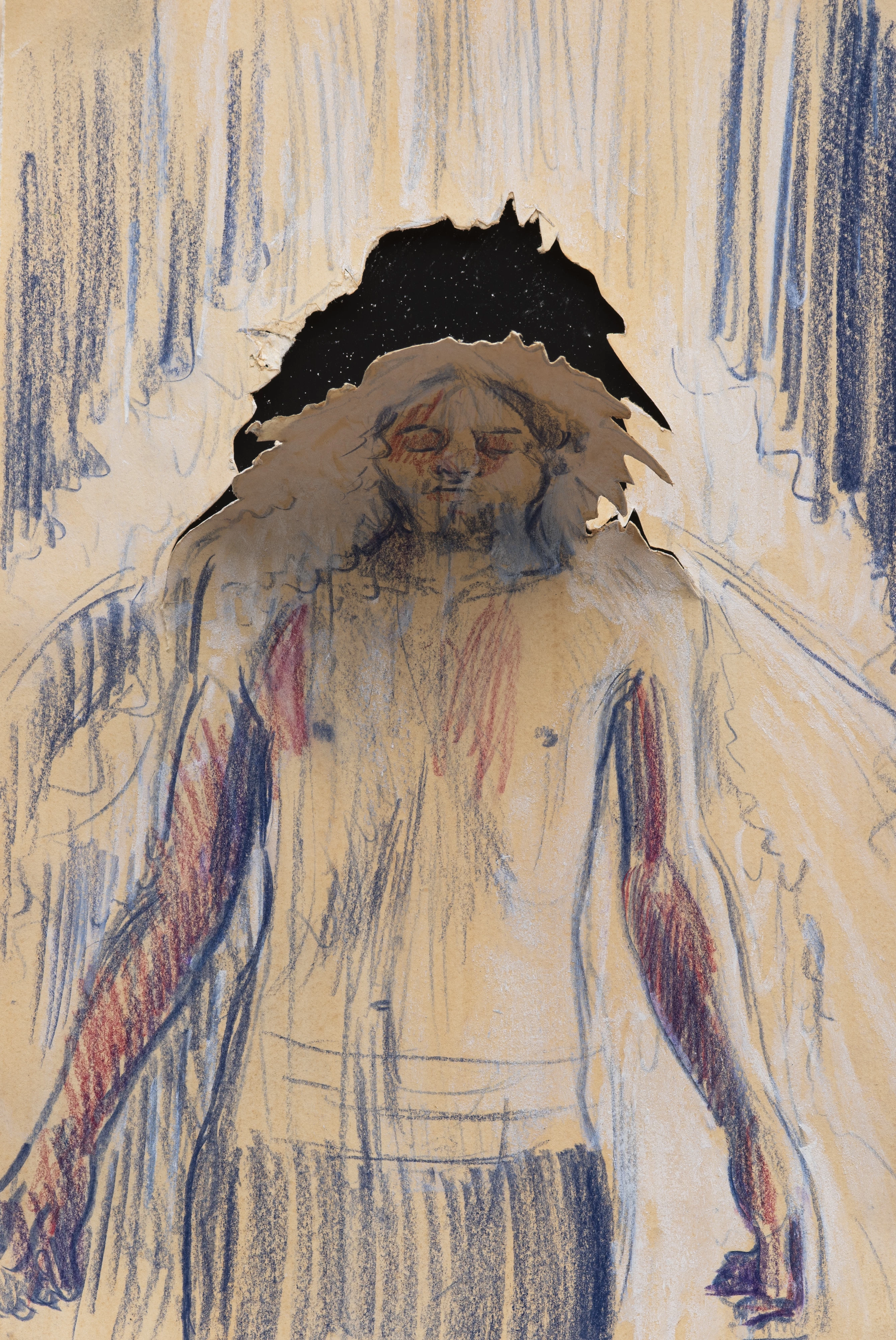

Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness) starts with a semi self portrait standing underneath a waterfall, eyes closed and meditating. The water, as it strikes the head of the protagonist is the device that allows the viewer to travel through the picture as the water moves up and down the paper and progresses downstream. The water moves past ‘scenes’ and encounters. Time does not move in a linear fashion as the water rushes past ancient figures, in tune with nature at one bend, encountering a laptop and cars around another. Nor do the images depicted stay within the realm of the ‘real’; reflective of tricks that can be played by our consciousnesses. Or at least, mine. It is a representation of work I do on my self, my consciousness, to gain clarity of mind. This work is a 1m by 2.3 metre drawing on paper brushed with a pink ground, using a limited palette of white chalk and blue coloured pencil.

EVANS, Geraint Ross, Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness) © Geraint Ross Evans

Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness) started with my own visits to and immersions in, waterfalls in South Wales, noticing thoughts and emotions throughout this experience to add as much depth as possible to the work. In parallel to this, desktop and museum research was a key part in moving from idea to the page. Typing ‘waterfall’ into the Celf Ar Y Cyd search rewards the researcher with 59 results. A mixture of paintings, prints, drawings and photographs. All depicting falling waters’ vertical journey. Here I’ll explore chosen pieces, and a much shortened version of the process that culminated in Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness).

Encounters in Waterfall Country

William Weston Young’s numerous ink drawings are delicate and meticulous in their rendering of nature. The feeling is a scene within a distant window frame. This makes sense, Young is clearly interested in the picturesque. He made these drawings to illustrate Young’s Guide to the Scenery and Beauties of Glyn Neath, published in 1835. He wanted to make Glyn Neath’s waterfall country accessible. Your weekend retreat from a week of 19century toil and industry. Could he have envisaged the car parks?

Often, small figures are living out their weekends at the base of his waterfall drawings; fishing, reading, prospecting. A human sized reference that invites our imagination in to occupy the space.

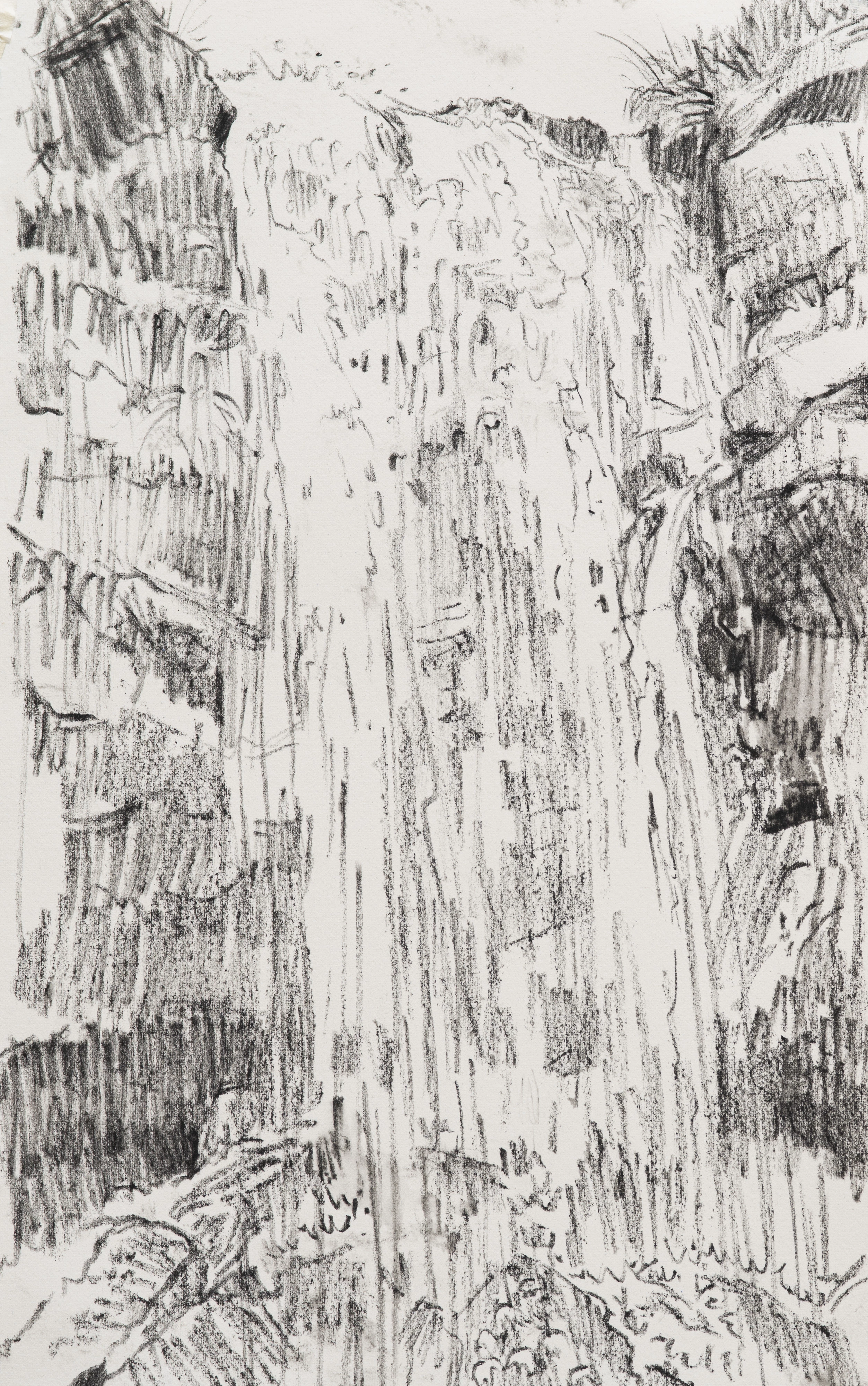

John Piper’s ink drawings are in stark contrast to Young’s. Both his waterfall drawings in the collection explore their subject’s verticality, with images that tower above us. We now stand where Young’s figures are depicted, we see through their eyes.

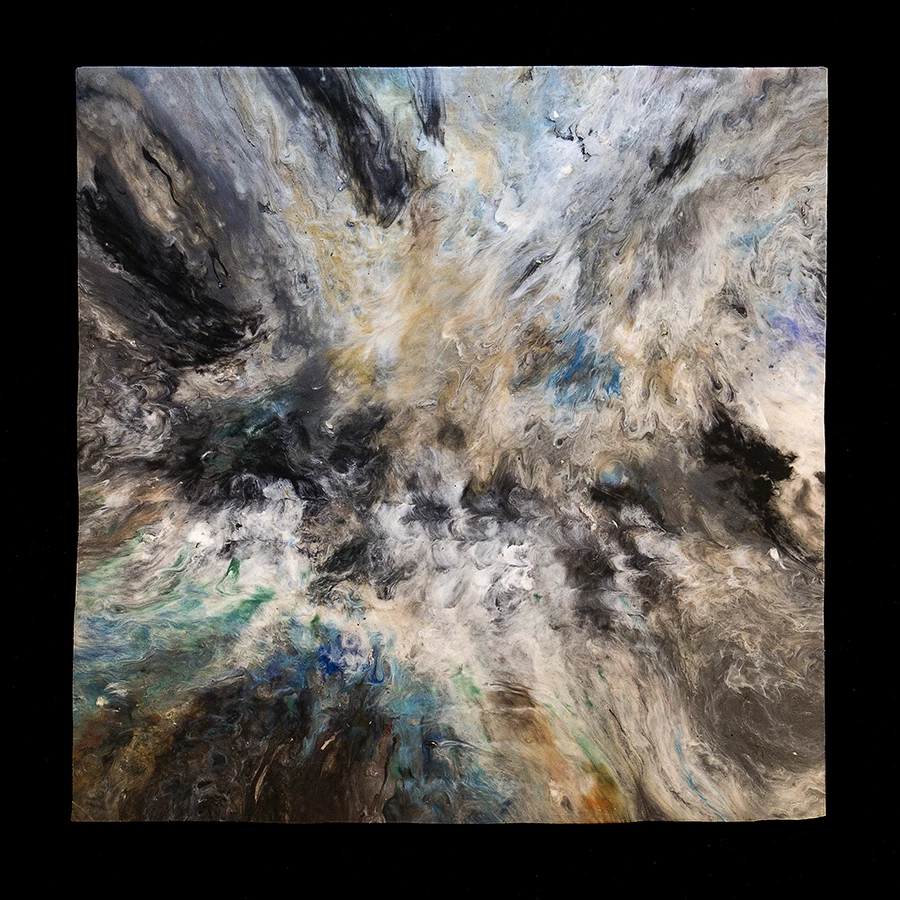

Piper pulls forth a huge expression of rock and water textures in ink; wiry lines, mop like brush marks and smokey mist applied with perhaps balsa wood; the mid century equivalent of a drying out marker pen. It’s easy to imagine the influence of Chinese landscape painting here. His work is wilder, born out of his experience of being there, an encounter.

Piper’s onsite drawing Crooked Anvil Pyrddin feels saturated by its subject’s microclimate. The spray has penetrated the page giving the rock the look of dark water with the waterfall itself, having been kept cleaner, appearing more like rock.

There’s a weight to the darkness here. With the literal absence of figures the human presence is experiential and psychological. The drawing is an artefact of place and feeling in a way Young’s safe distance doesn’t offer.

I find an understanding within this work. I sensed this weight and wildness with my own cold water immersion in the falls above Blaenrhondda and Glynn Neath. In December last year, I made my preparations to greet the cold, forceful waterfalls. I’m under dark, dripping overhanging rock, undercut by time. I imagine the family of beasts that eek out a life within. Eventually I commit, enveloped by the rushing water, biting cold and surrounding roar. A gateway to our distant and primal beginning. Sprinting heart and shallow gasps slow as I gain control. My mind grows quiet.

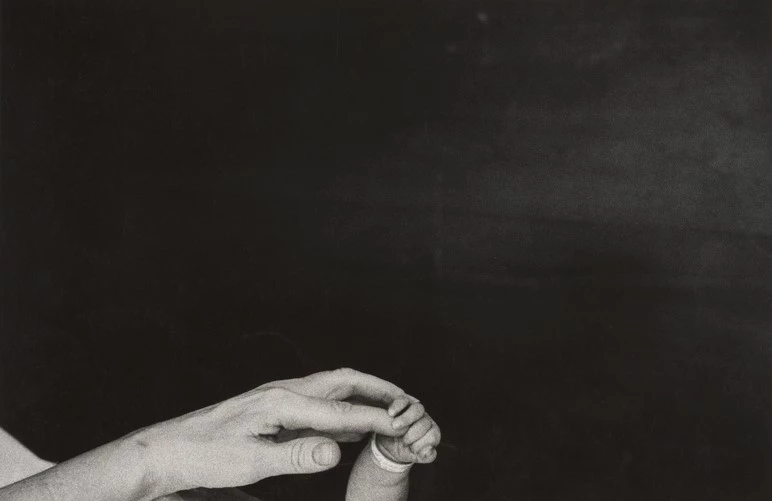

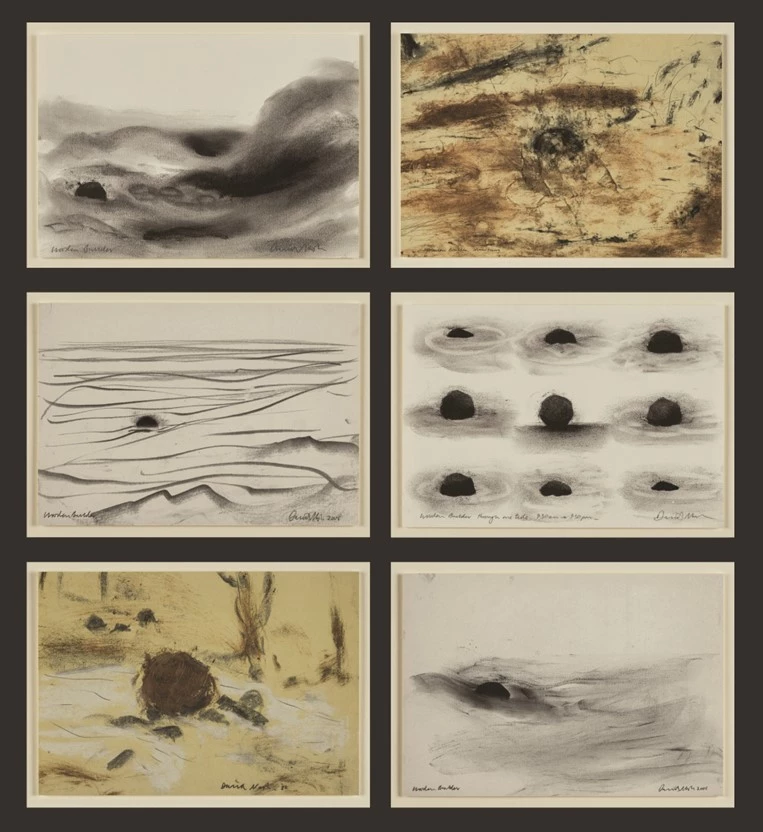

Dry, I find a small island. I use this quiet to make studies of where water meets pool, exploring movement through shapes, patterns and texture, finger tips white. Antithetical to the selfie stick, it’s the drawing process not the outcome that is the focus here. The marks show traces of connection to the external world. Eventually the paper gets too damp and my charcoal pencils slip dark sticky marks across the page. Time to go.

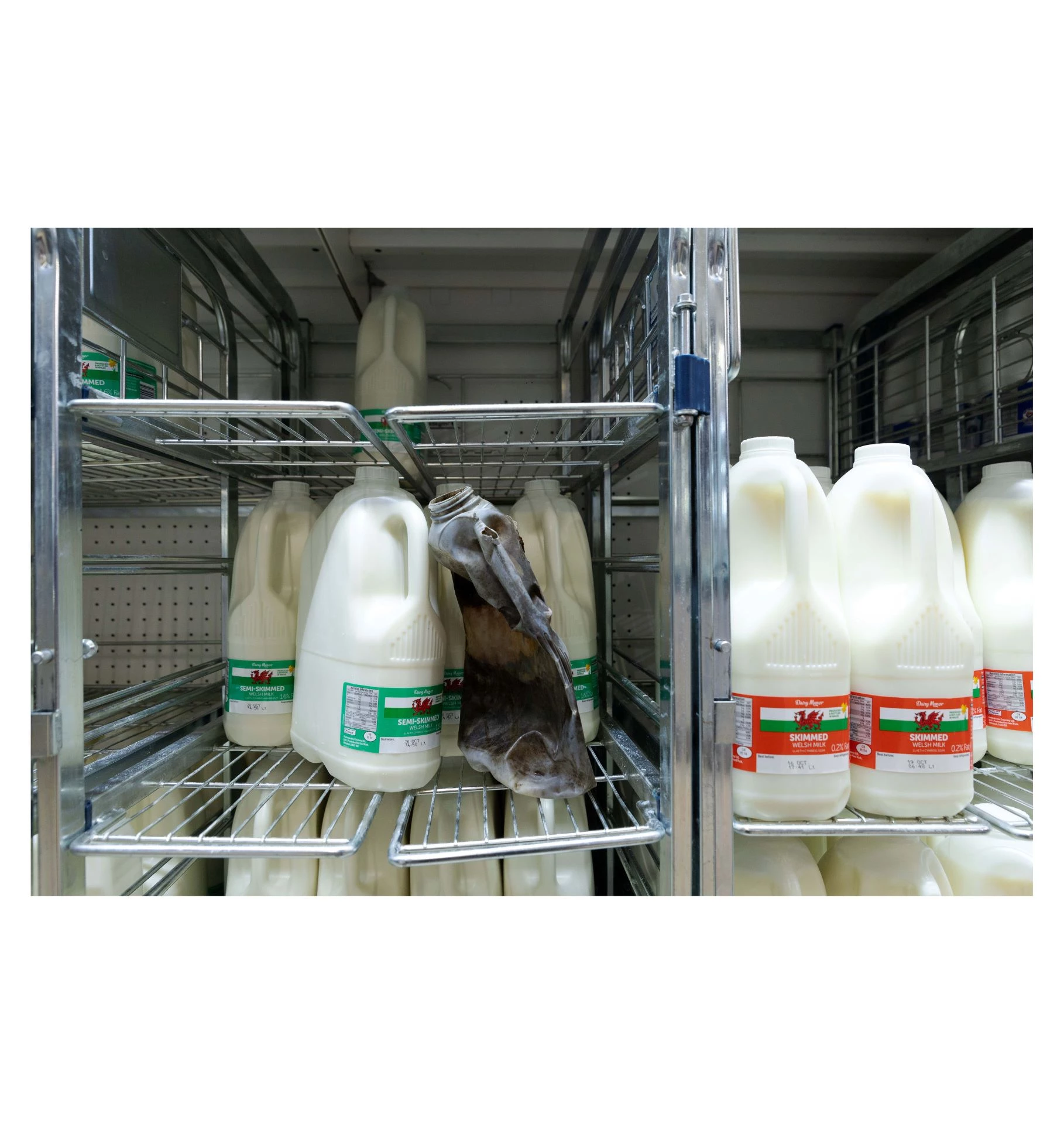

The volume fades as I slowly re-enter “society” via a series of signposts; the remnants of a fire, some contorted iron, my upside-down footprints in the mud, a small concrete damn, an empty beer can, a footpath, a plastic bottle, another empty beer can, plastic flowers tied to a gatepost. The distant sound of a road shatters what’s left of the wilderness’ spell.

Back at the studio

I reflect on my experiences, my explorations and research. Young and Piper’s images share their roots in the particular. Whether encounter or communication, they describe places. With Stream of Consciousness, I want wider reach. To express multiple thoughts and feelings that shape the human experience. A journey that necessitated expanding the view beyond the waterfall, following water flow progressing downstream through stages of a river’s life.

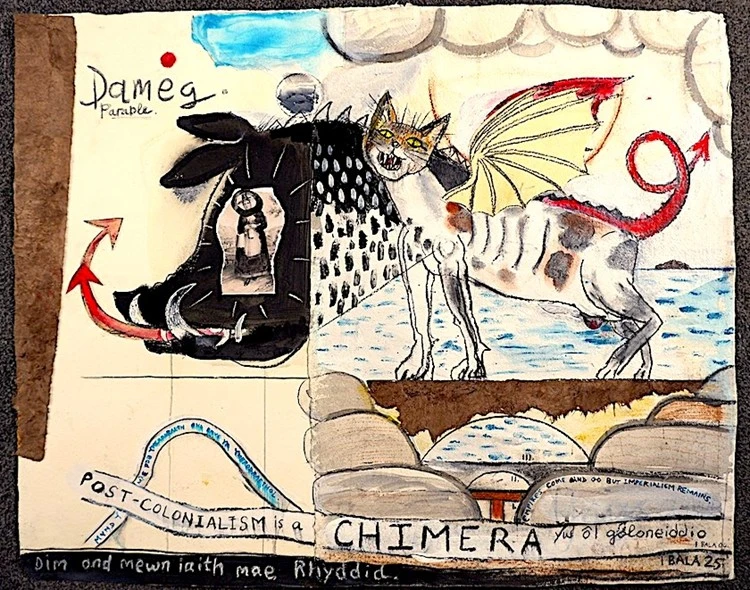

I use image making as a playground to explore ideas. Whilst making Stream of Consciousness, I’m considering what it looks and feels like to be alive at this moment. How inner and external experiences are married. My drawings are experiments, this one no different. I need them to help me make sense of feelings, thoughts and observations that are not encountered together in reality. In Stream of Consciousness, I consider;

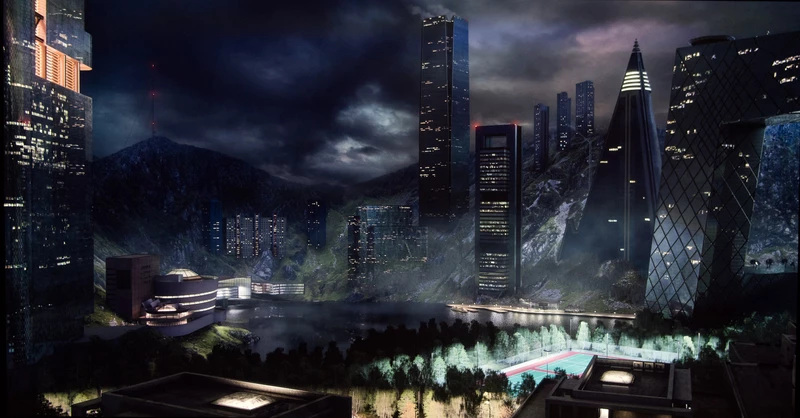

How do we engage with our waterfalls and river today?

How do the pollutants of the mind manifest as pollutants in the real world?

Can understanding one's mind help us find the strength, courage and insight to change things for the better?

Surrounded by observational drawings, memories and imaginings; I set myself the challenge of letting go, drawing as subjects came to mind, not questioning their importance, value or place. The watercourse itself became a ‘stream of consciousness’. The mind’s ‘pollutants’ are visible entering the waterway, manifesting as real pollutants obstacles and distractions travelling downstream. My own meditation on contemporary issues able to derail us as individuals and members of a global population.

My drawings, including Llif yr Ymwybod (Stream of Consciousness) were recently exhibited as part of ‘Silent Revolution / Chwyldro Tawel’ a joint exhibition with Sue Williams at BayArt in Cardiff.

Geraint Ross Evans is a figurative artist from Cardiff who uses drawing as a playground to explore complex contemporary issues through the lens of people and place. He studied at Swansea Metropolitan University and the Royal Drawing School in London, where he now teaches. www.geraint-evans.com @geraintevans_artist