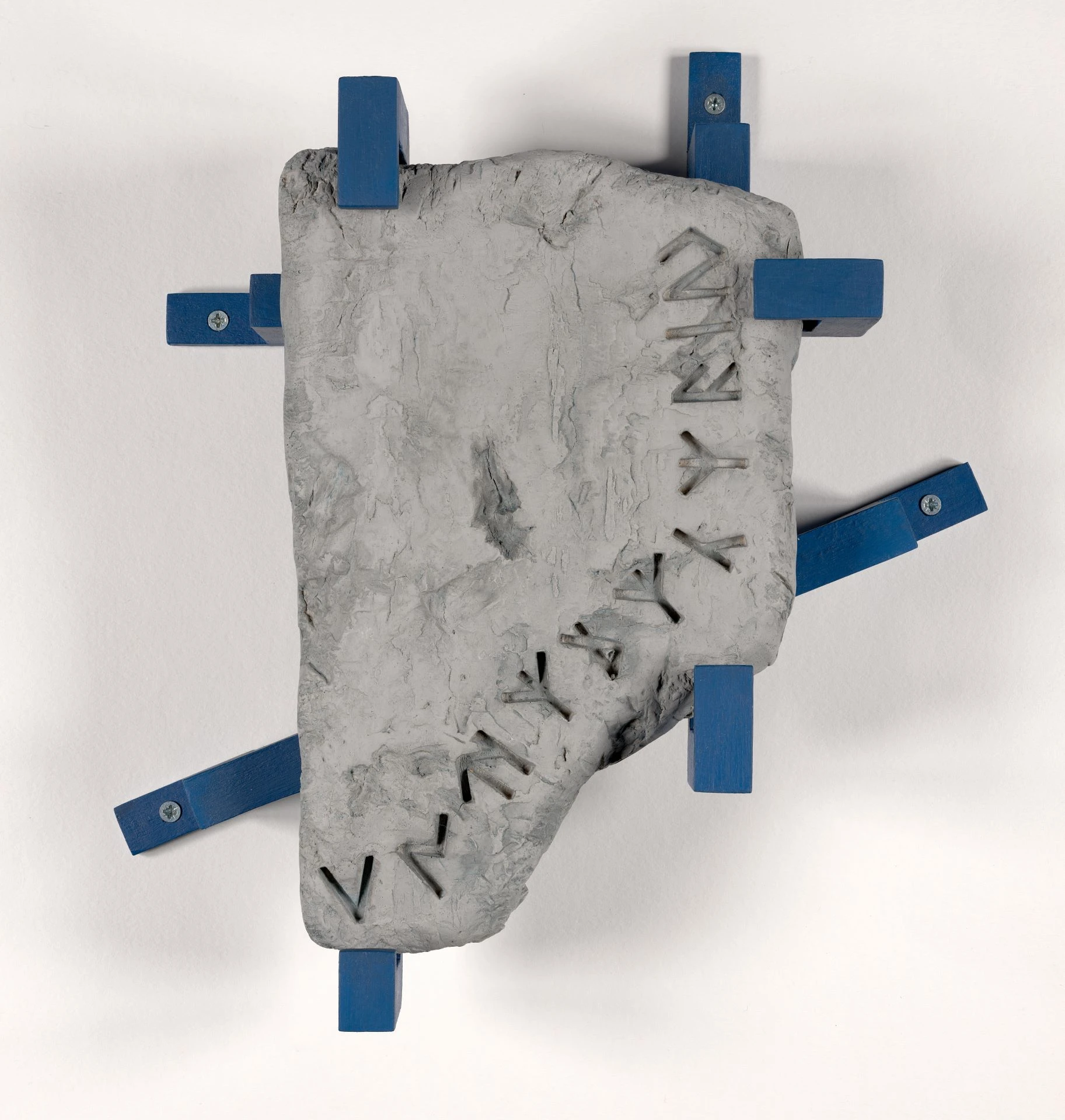

We were down in the archives. It was my first time. A dark, treated room, teeming with canvases, decorated in everything from pigmented oils and turpentine to dust and foreign scents. All the works there were protected earnestly: fixed upon grids, conserved and, at times, resurrected by wonderfully diligent conservators.

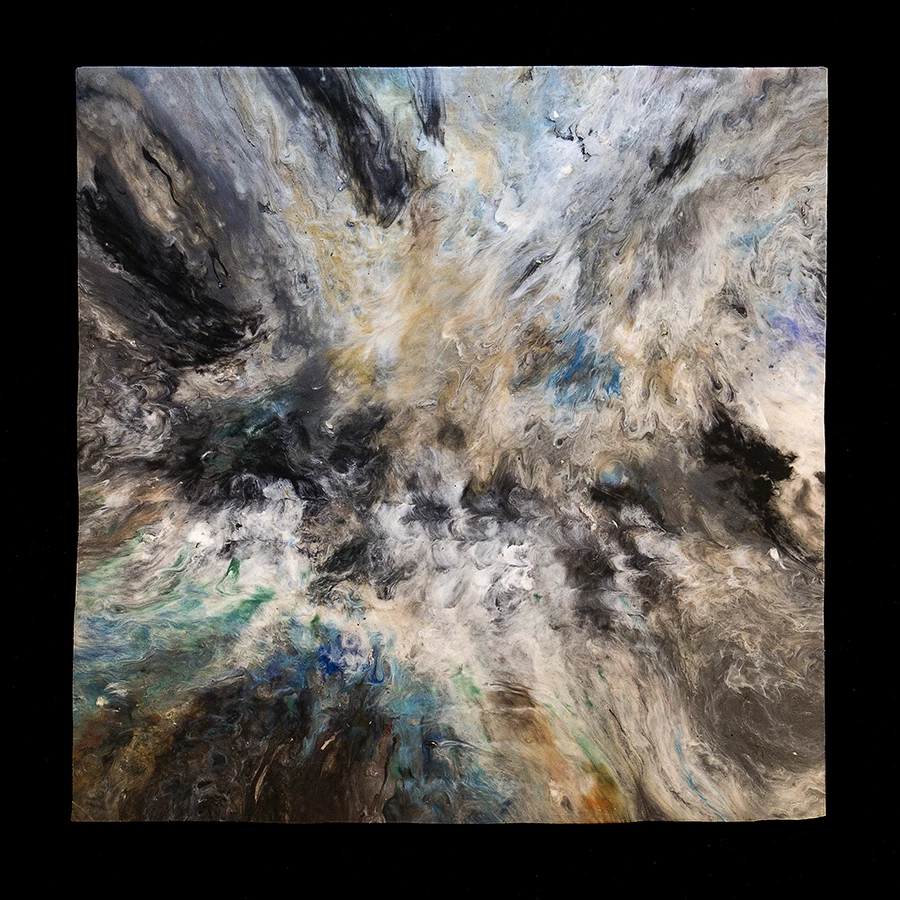

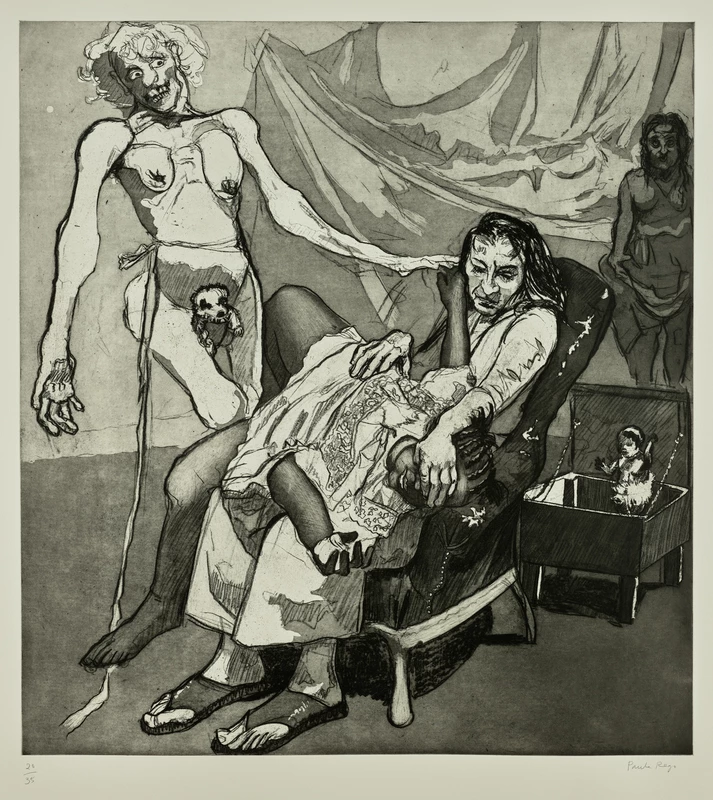

I saw so much incredible work, so much that had never seen the light of day. Names that I have heard of, but never had the privilege to see. Then I witnessed the unknown. Halfway through the tour, they pulled out another rack of imposing artworks. Amidst all the artistic brilliance, I noticed a piece that appeared to be a bit more ‘obstinate’. Obstinately brilliant.

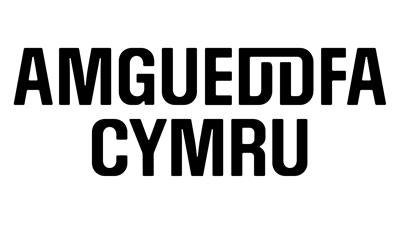

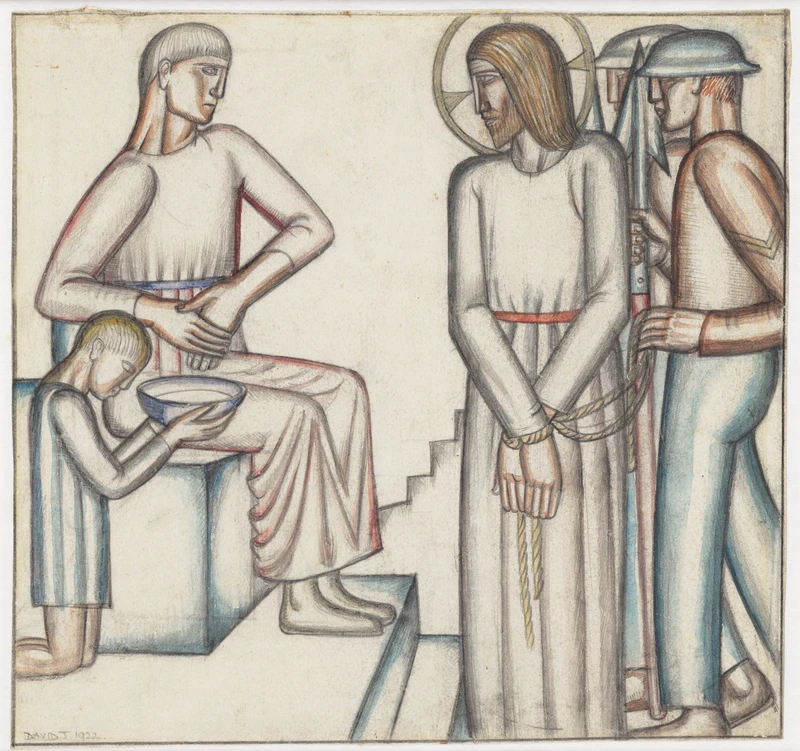

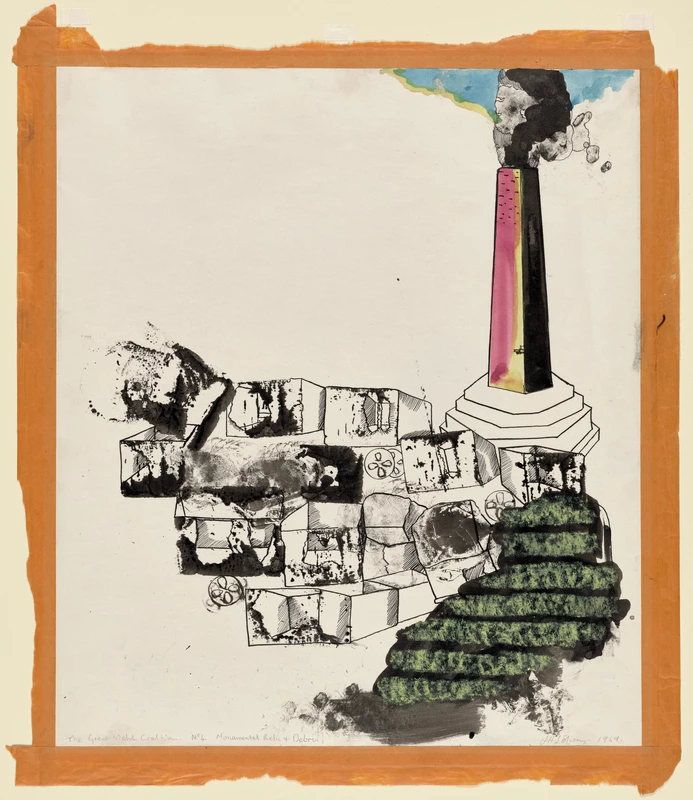

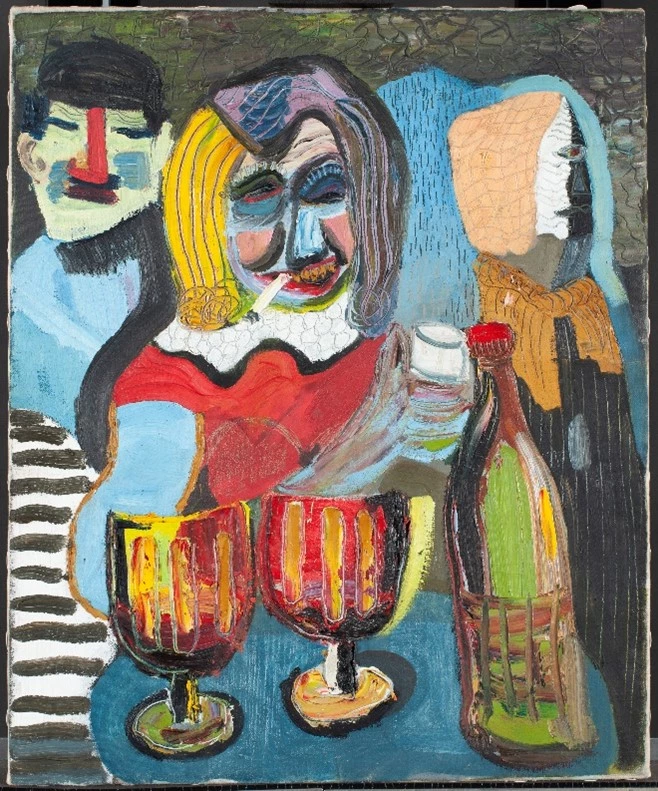

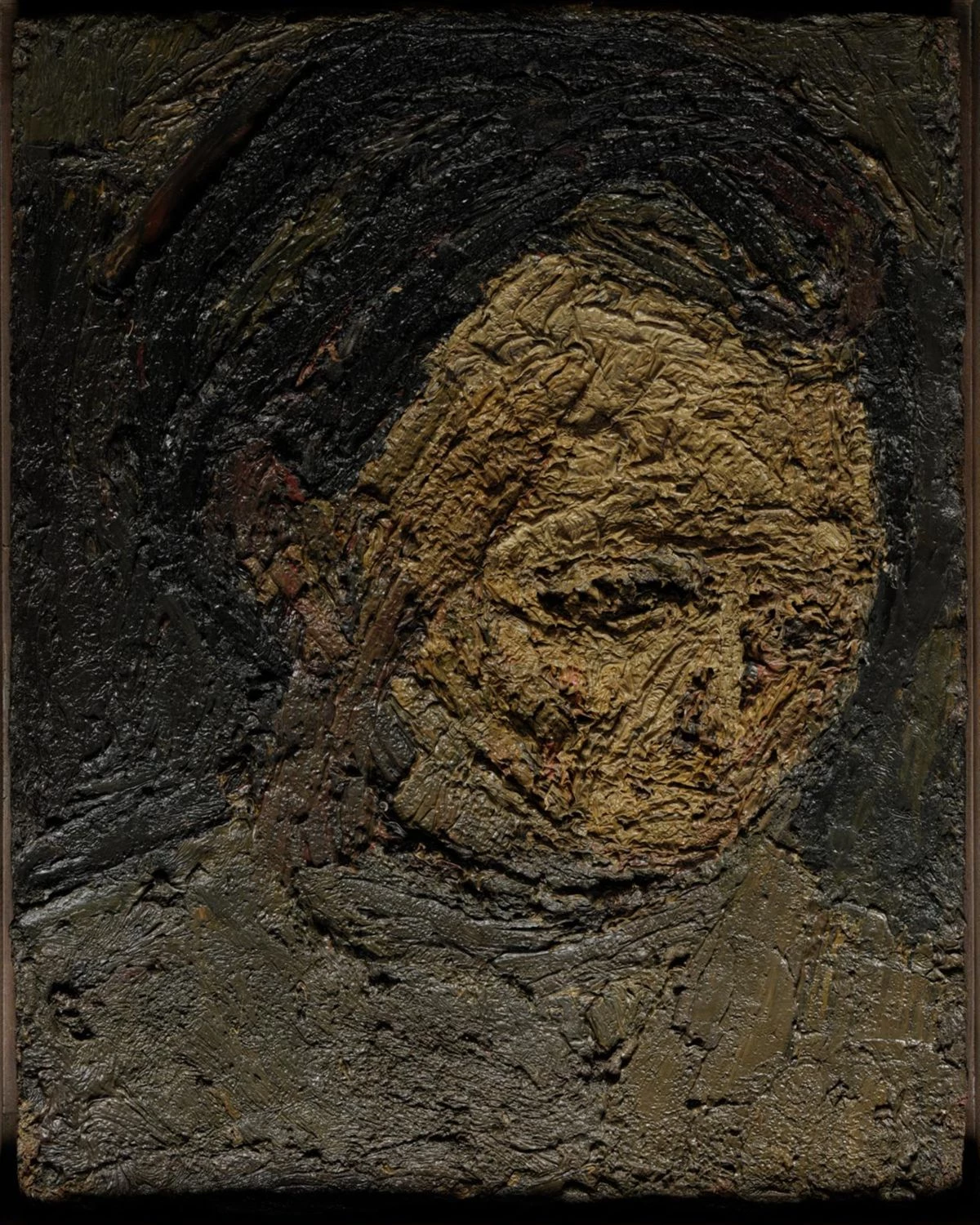

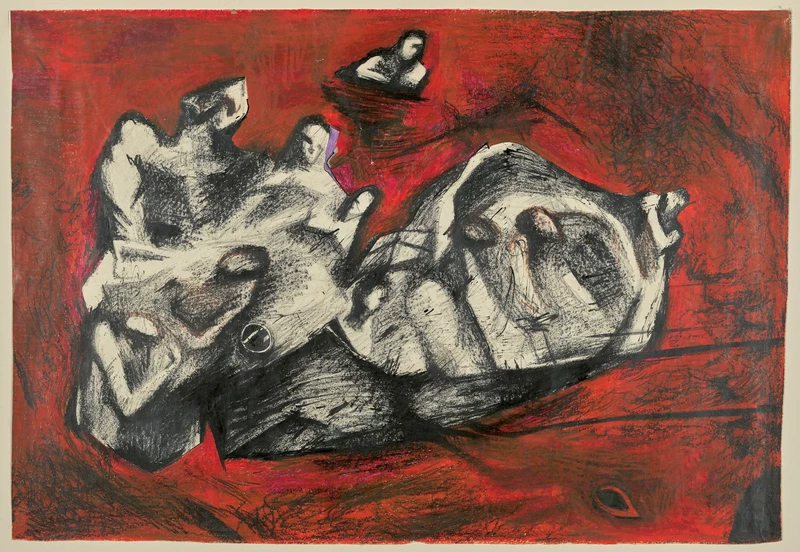

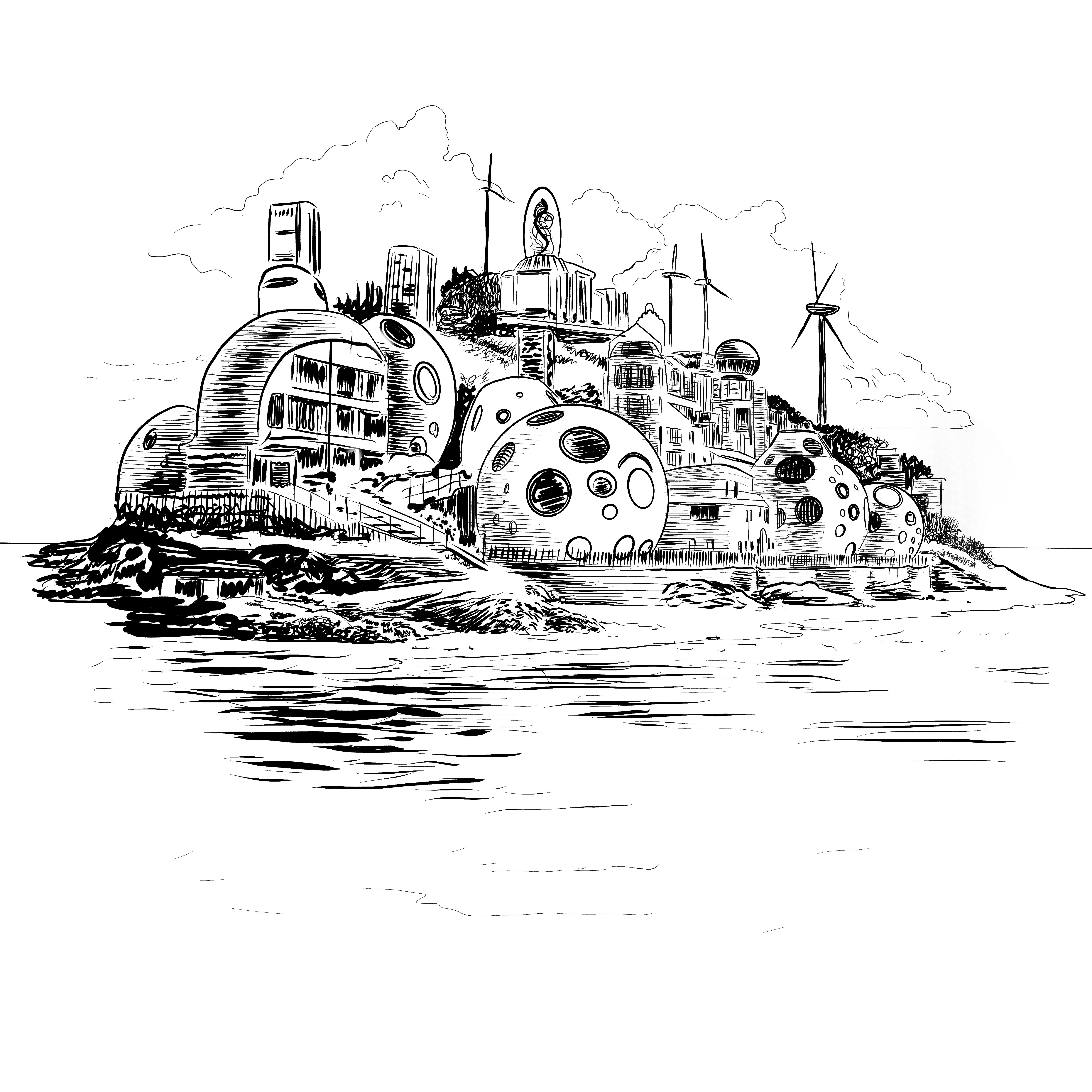

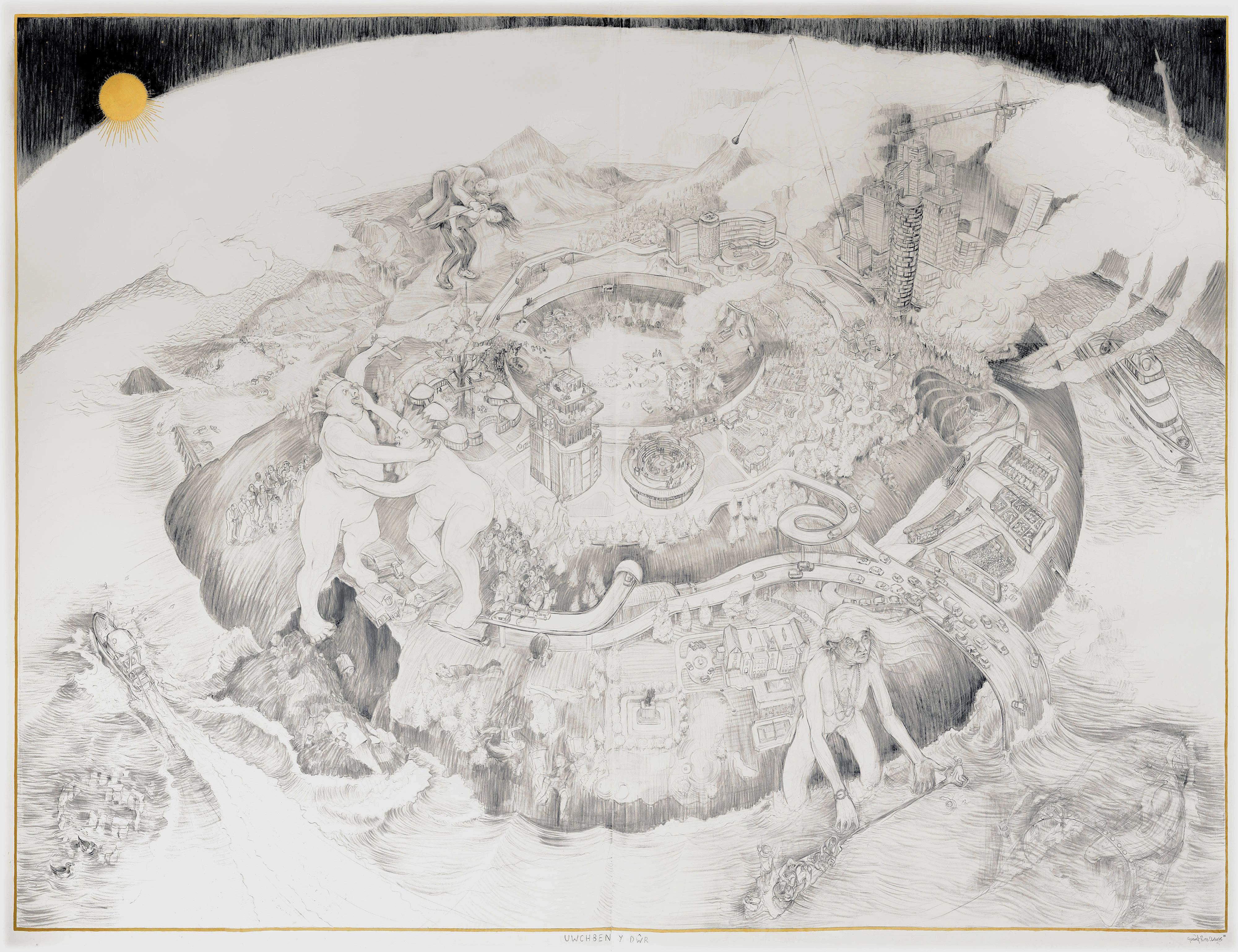

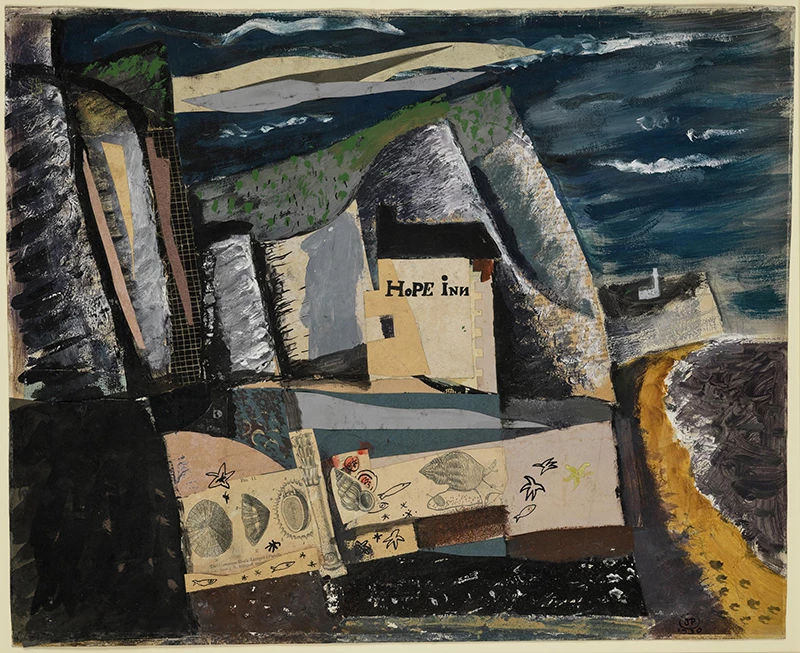

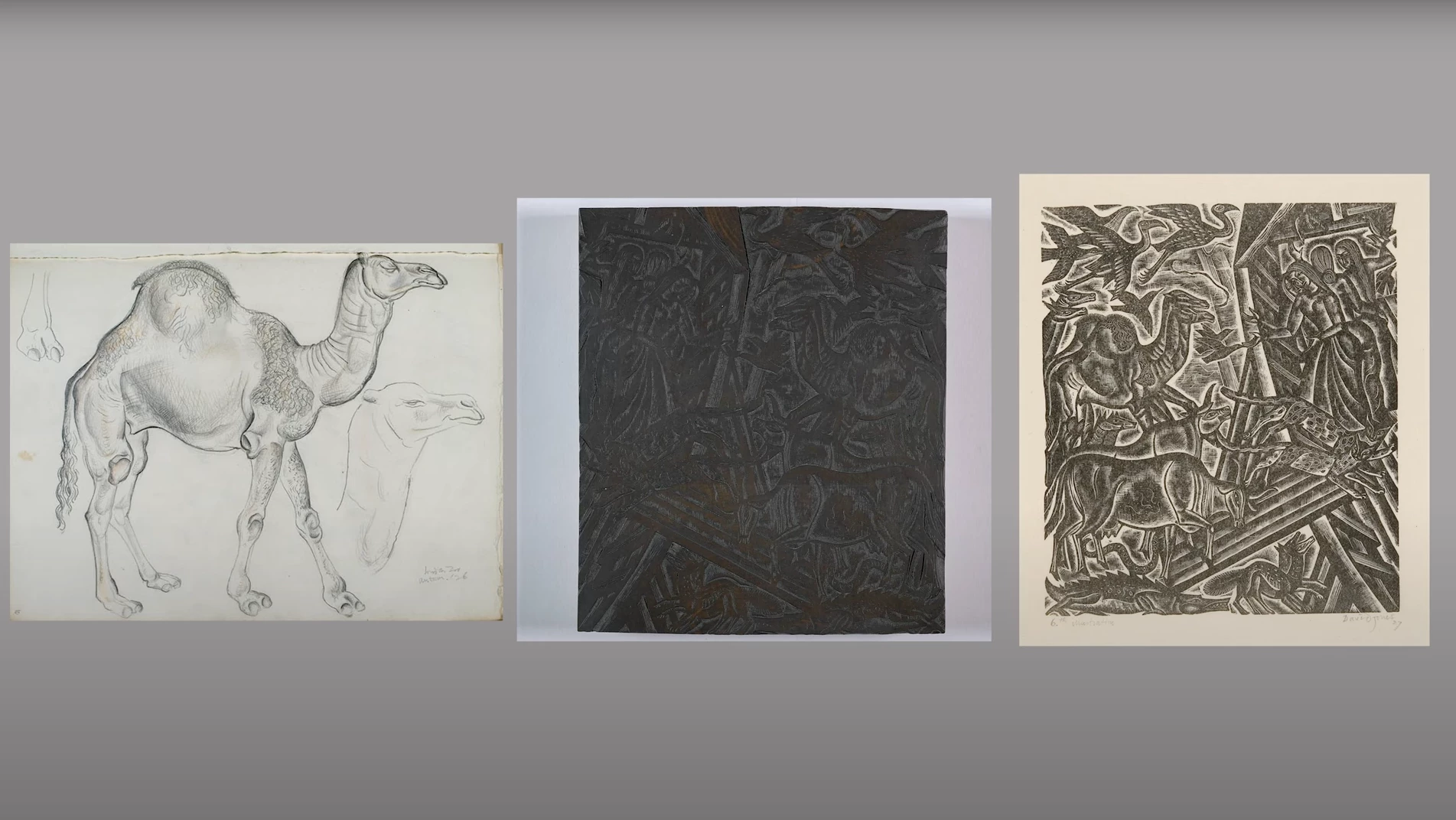

I was always told that it was rude to stare and I promise that I was raised correctly – and yet, I couldn’t help it. I was so struck by this piece, the charmingly bizarre composition, its playful use of perspective, the muted colour palette, paired with gradients and depth. I had so many questions, but perhaps, the most important one of them all was – who is this? Followed by a question equally fused with bemusement, as I racked my brain, trying to figure out how I had been ignorant of this person’s work for so long.

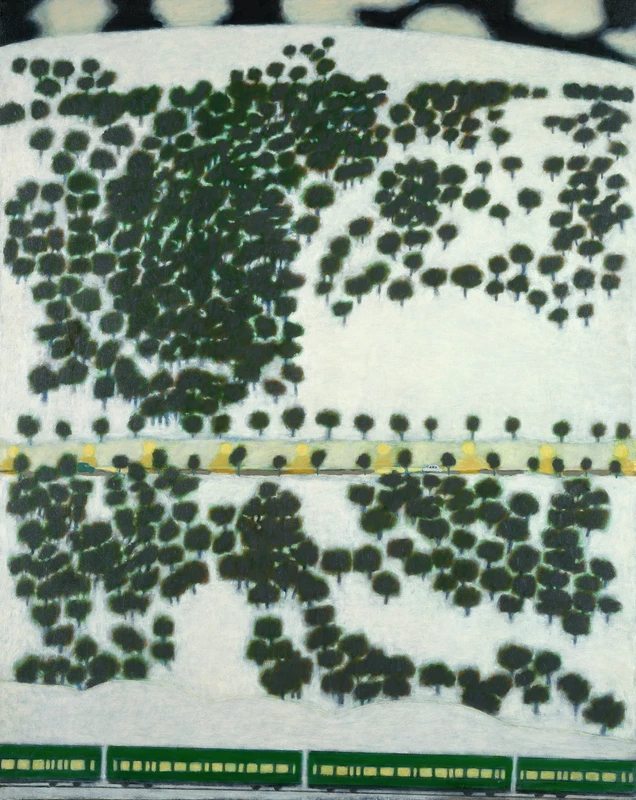

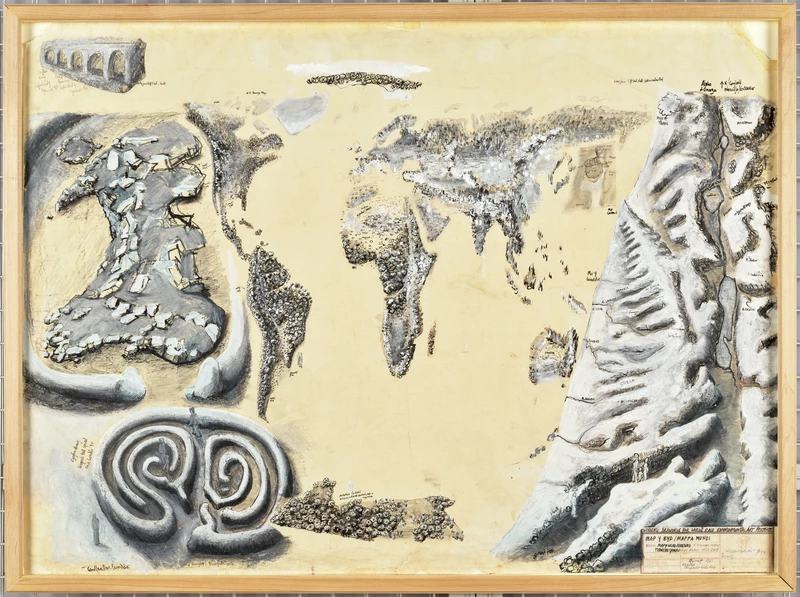

His name is George Poole, I was told. Wales’ own homegrown talent. Despite this, however, throughout his career, he never had a single exhibition in Wales and unfortunately passed away: an artist whose levels of critical acclaim were not commensurate to his levels of skill and ingenuity. So, what went wrong – if anything at all?

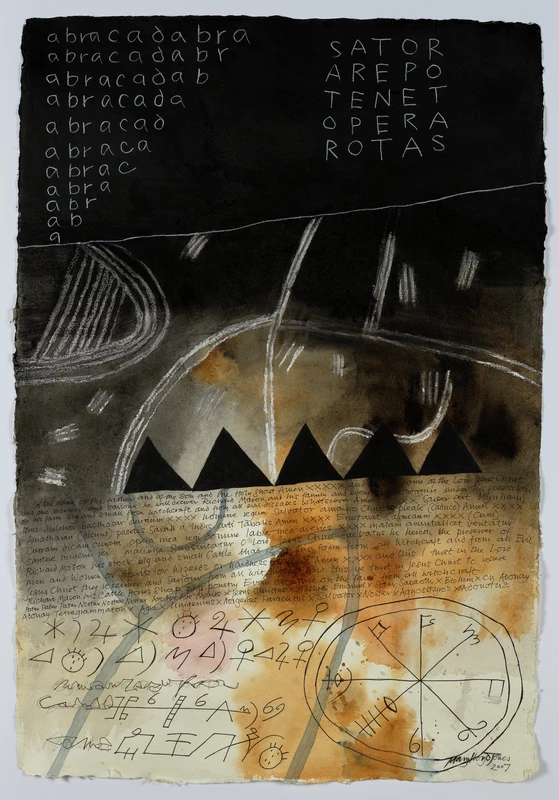

Poole’s life story is as equally as riveting as his works. The socialist Rothschild descendant whose anti-establishment sensibilities saw him at odds with the art world, would be my sensationalist headline. However, for the more nuanced assessment, there is a lot more that we need to consider.

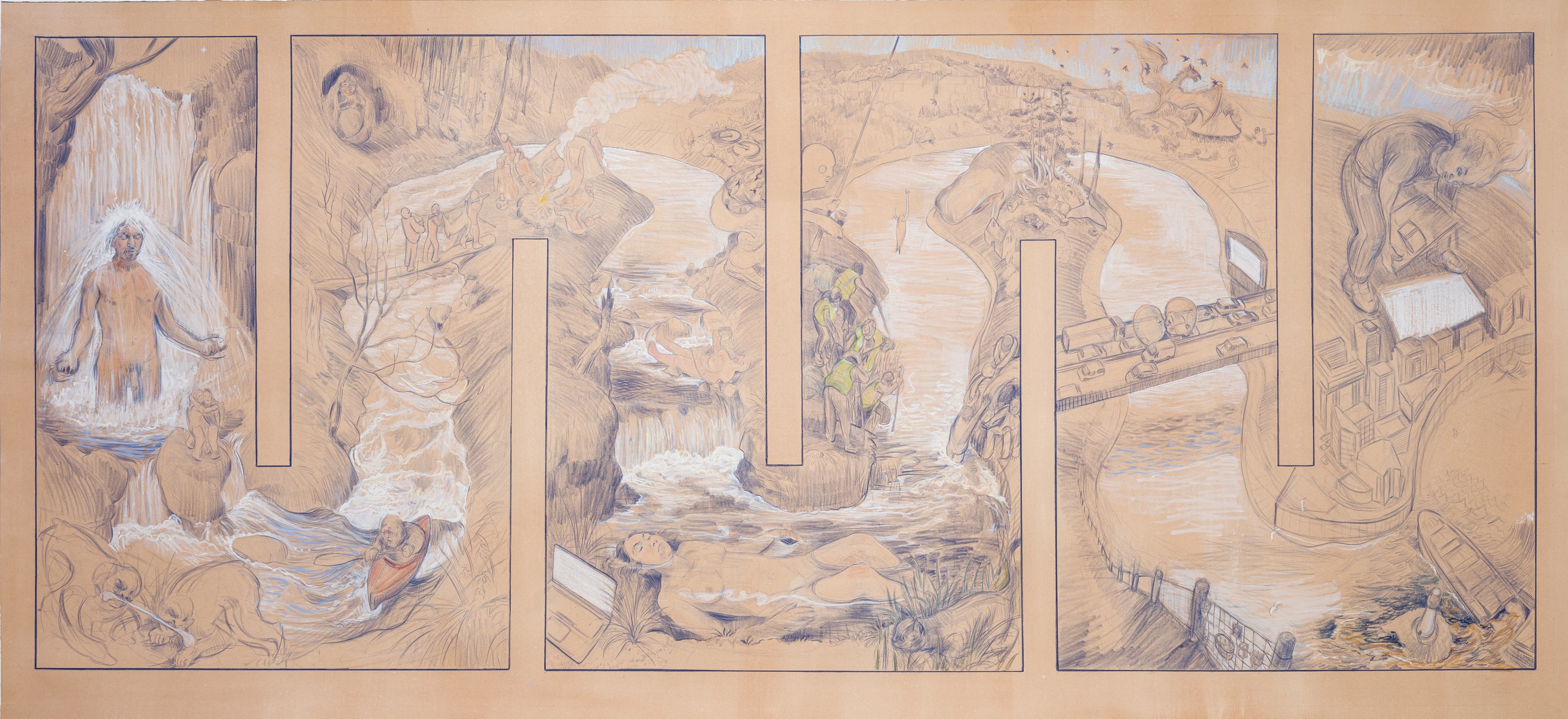

He was born March 28th 1915, to two conscientious, working-class parents. His father, a dedicated communist miner and his mother, a servant to the aristocratic Mitford and Redesdale family. Poole bore witness to the ills of classism through his father’s unwavering commitment to his political beliefs. By contrast, the nature of his mother’s work, I imagine, may have been somewhat of a moral quandary or conflict of interests; interacting with such affluent individuals that have amassed generational wealth for centuries, appears to clash, ever so slightly, with Marxist praxis. In this way, it can be seen that Poole grew up seeing the symbiotic relationship between the ruling class and the proletariat; the workings of the rich and the struggles of the poor. Poole’s family always seemed to be on the periphery, observing the rich whilst remaining true to their working-class roots.

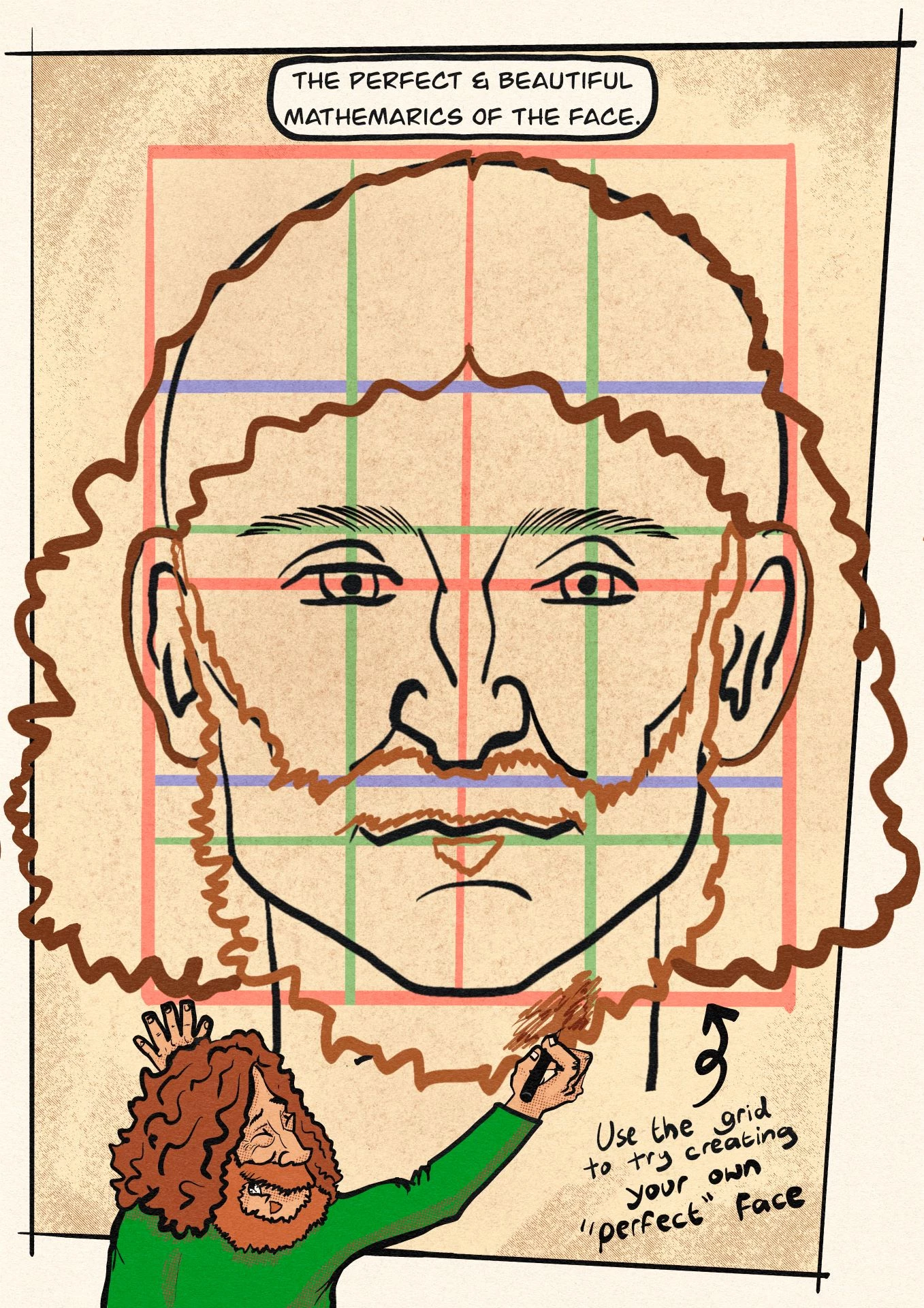

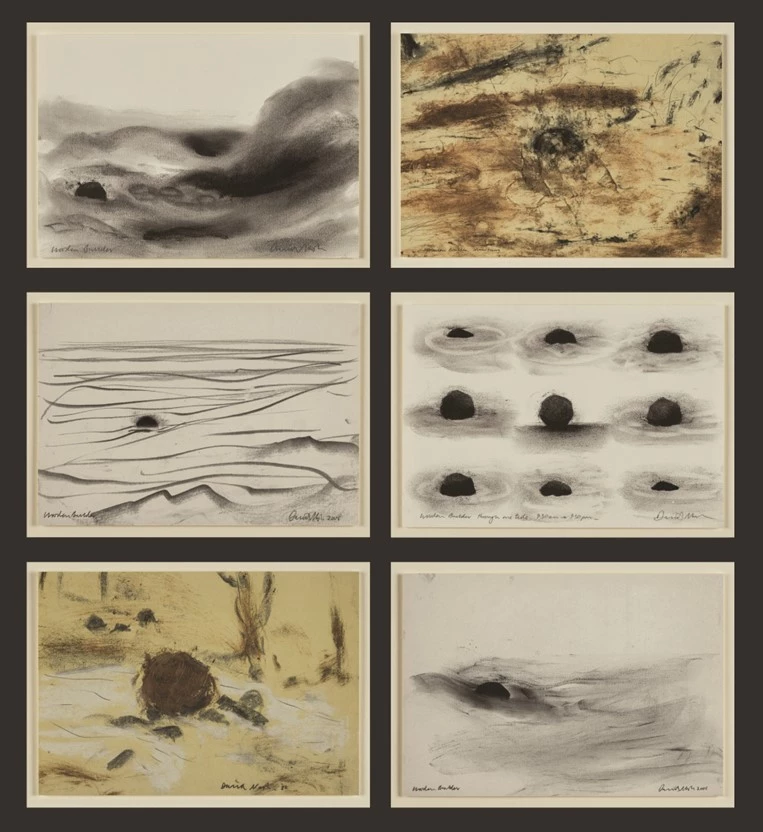

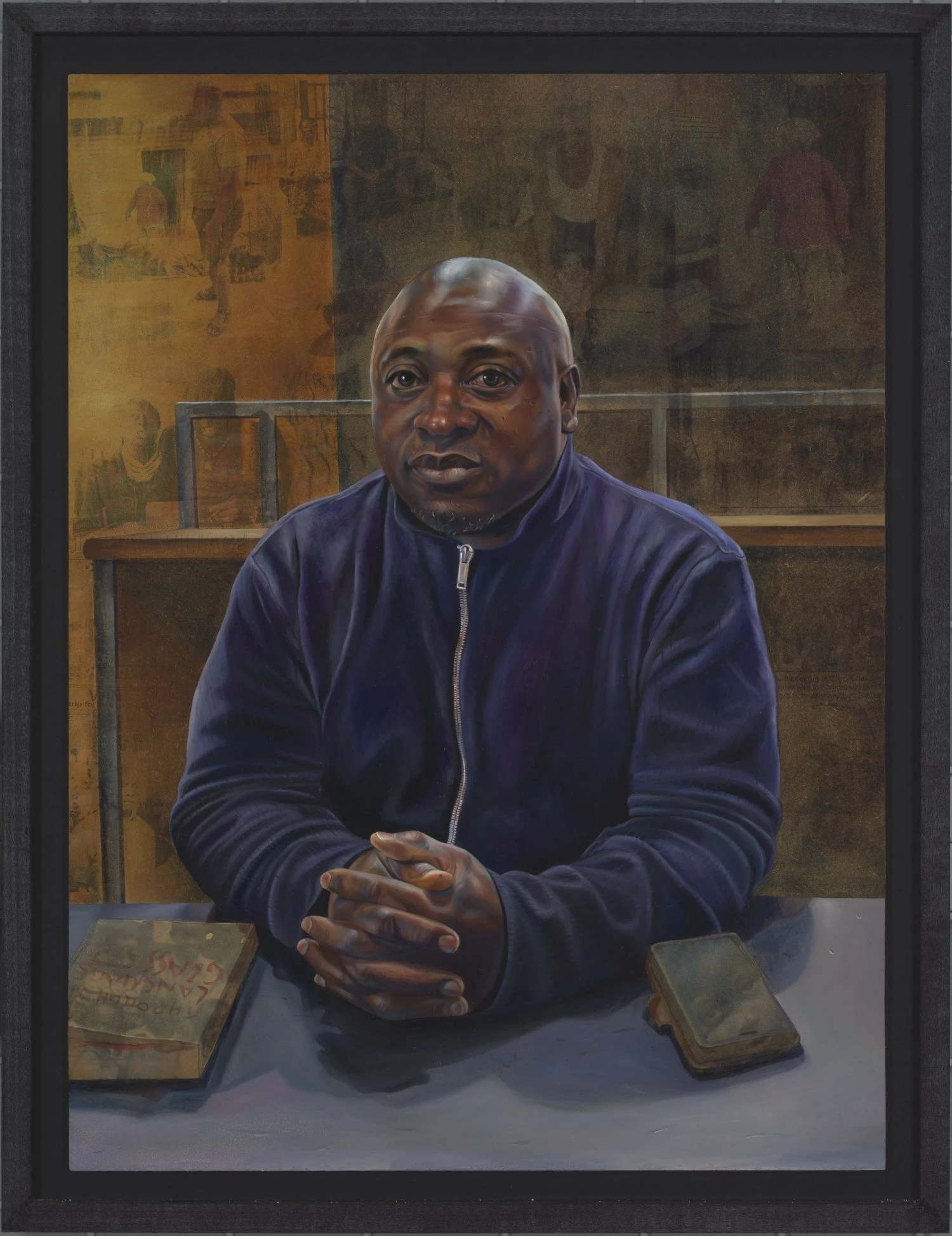

As aforementioned Poole was a Rothschild descendant by virtue of his grandfather – an illegitimate child of the aristocrats, allegedly paid off with a fee of £3,000,000. A fee he subsequently spent in its entirety, indulging in horse racing and musical entertainment. Somewhere in this revelation potentially lies the perfect metaphor to describe the artistic ventures of George Poole. Poole grew up in abject poverty and working-class conditions, yet he was constantly in close proximity to the rich, via his ventures into the art world. This purgatorial dwelling between these worlds that Poole occupied made him best equipped to tackle the “social realism” that he became associated with, defined by Poole himself as: “To understand reality, meaning, function and purpose of man. To portray man’s striving for perfection without the embellishments”.

Poole was an artist driven by purpose, firmly grounded in reality. Unfortunately the ‘embellishments’ he consciously chose to omit were the primary concern of the establishment at the time. He was someone that endured many challenges; from life-threatening ulcers, to serving time in prison and being blinded in one eye, yet one of his biggest challenges was trying to navigate a system that appreciated his genius but failed to appreciate every facet of who he was. Art critic John Berger adjudged the former communist to be ‘obstinate’, as he refused to compromise his practice, yet still craved critical acclaim. His time spent studying in London aided Poole tremendously in garnering a following, with the likes of the Royal Academy, Battersea Library and Crane Gallery all clamouring to exhibit his work. When things like this are happening, why is there a need to compromise? I am sure that his innate calling to paint, in tandem with the recognition he was receiving across England, served as enough motivation to keep creating, despite his cynicism and distrust of the art world.

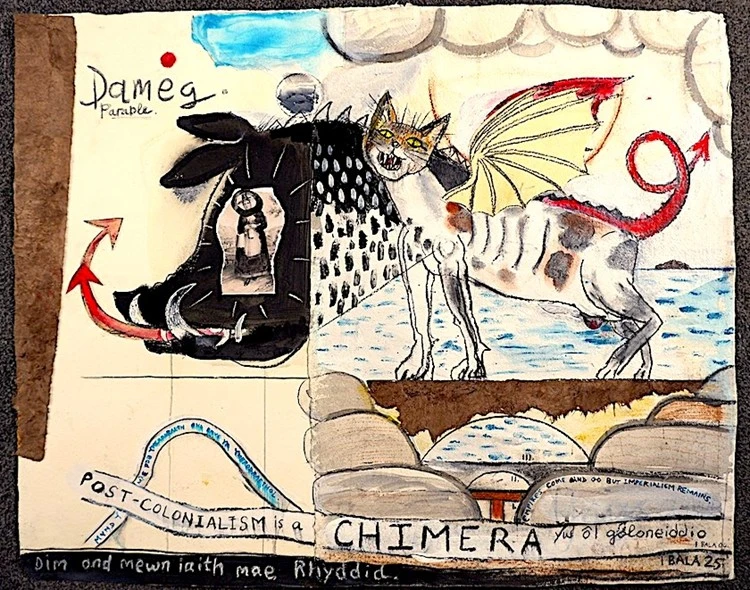

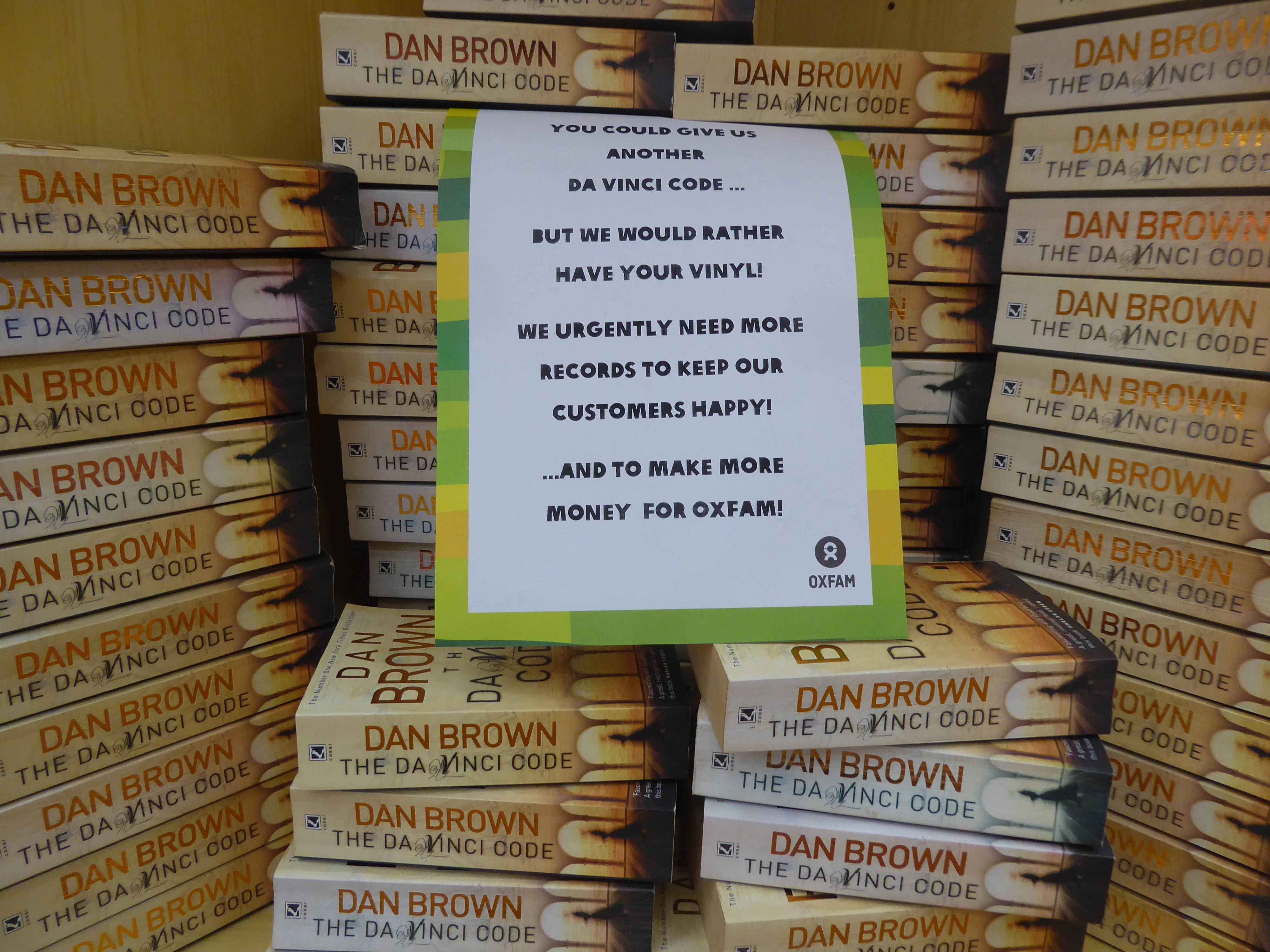

This appears to be a tale as old as time. Posthumous recognition – life after death. The lovable depictions of British community life by LS Lowry are now very much the pride of our national galleries. However, during the time he spent with us, he was often ridiculed; from the disapproval of his working-class upbringing, to the mockery of his paintings – he was seen as “cloth cap nincompoop”. The much lauded Vincent van Gogh only sold one single painting throughout his life, gaining widespread recognition long after his passing. In his final days Frank Kafka told his close friend Max Brod to burn all his drawings and artworks, as his efforts to be recognised for his works had proven futile. Poole’s work has been exhibited in Wales for the first time at the Rules of Art? exhibition, here at National Museum Cardiff, thanks to some bold senior curators and the fearless curation of the Demystifying Acquisitions Group, which I have had the privilege of being a part of. Perhaps we were not ready for his works back then. Someone so forward thinking, politically astute, yet adept and skilful. Poole’s mistrust of the art world was certainly not entirely misplaced. He is not physically with us to see the impact of his work, but we hope that this is a small step towards continuing to celebrate Welsh artists and showcase their efforts to the world. As the old adage goes, “Better late than never… but never late is better”.

Charles Obiri-Yeboah is an individual concerned with maximising creativity through an array of different mediums, from visual art to music and literature. Having studied BA Comparative Literature and MA Critical and Creative Analysis at Goldsmiths University, his practice is informed by postcolonial approaches, seeking to cultivate art, essays and spaces that encourage stimulating dialogue and conversation.