For Garry Fabian Miller

and for Peter Sedgwick

Who has not stood somewhere gazing at the sea

and at the sky, watching them both changing? –

even a quiet sea, as if pulsing,

breathing, or a sky all-over grey or blue,

undefinably and imperceptibly

responding to the slow revolutions

on its axis of our tilted planet

with its subtly influential satellite

and round the star which seems to us to climb,

visibly or invisibly, depending

on the vapours which can sometimes hide it,

until it’s almost but not quite directly

above our heads before it arcs down westwards?

Even when we cannot see directly

where it is behind the stratus, cumulus,

or stratocumulus, which like the sun

and east and west are words with which we cover

the naked mystery of the world we live in,

such sounds as save us from the shock of facing,

under a thin film of understanding

and familiarity, the challenge

of what we can never finish watching?

Who has not stood on a shore or clifftop

gazing at the sky and at the ocean,

with the line that we call the horizon

seeming to divide them, though we know, as with

the rainbow’s end, however far we travelled

we could never reach where it beckons us

to seek for it, as it is always shifting?

Who has not thought they’ve stood for too long watching

and, being human, having things that need them,

‘business and desires’, as Hamlet puts it,

shaken themselves, and turned back to their lives,

and afterwards wished they had looked longer,

because they’d only started to be open

to all the largeness that invited them

to grow larger themselves in their responses?

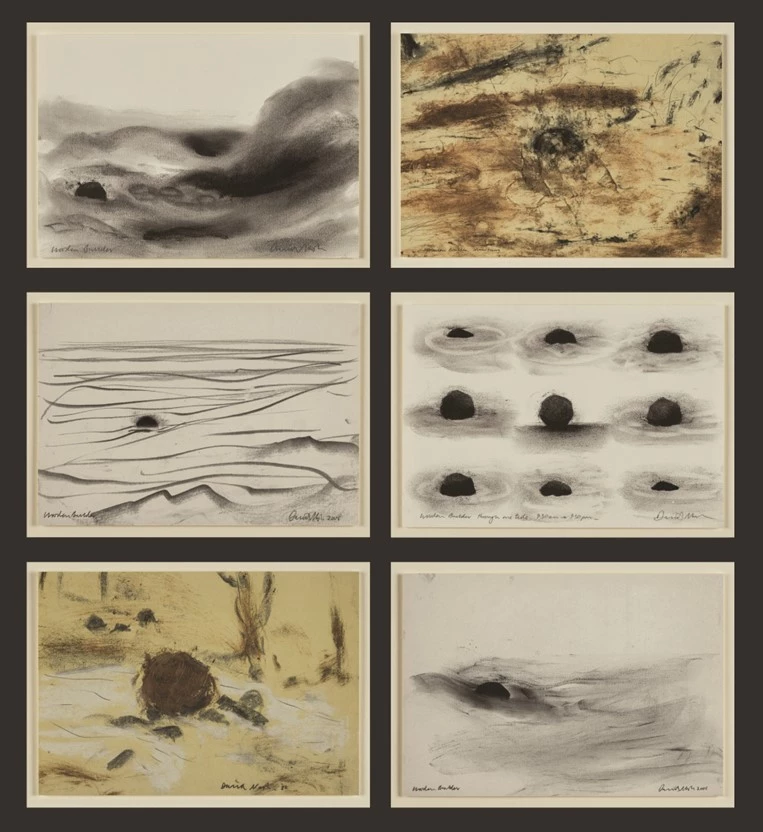

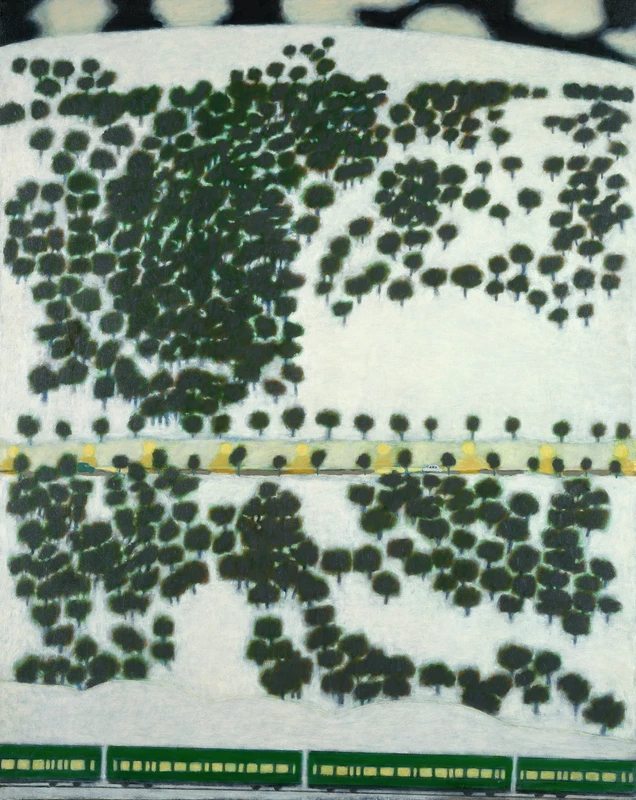

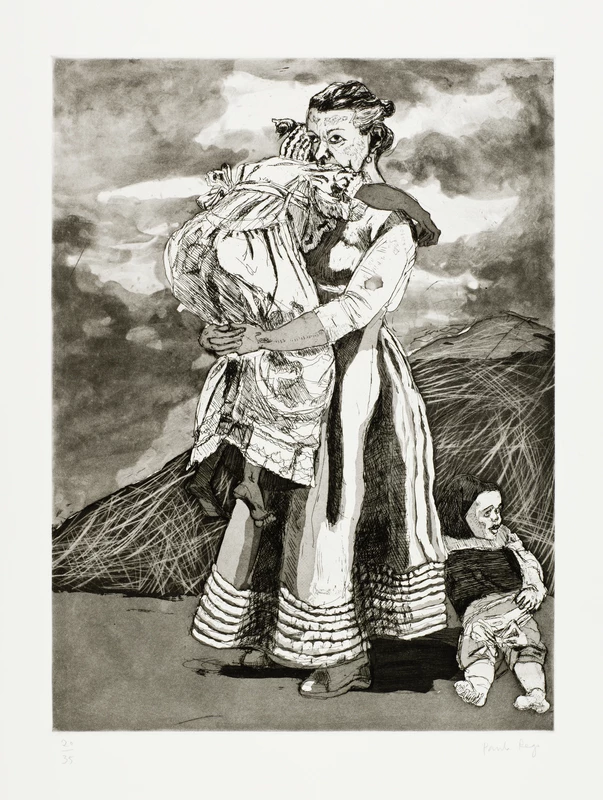

For them, for us, for me, for you perhaps,

as well as to discover who he was,

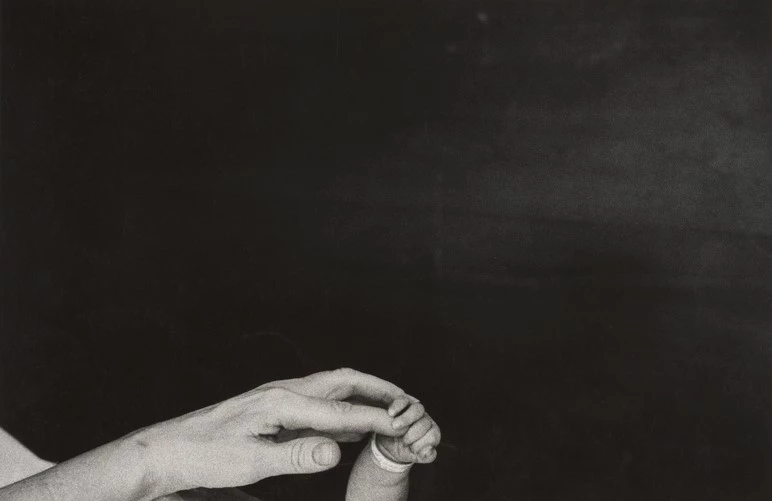

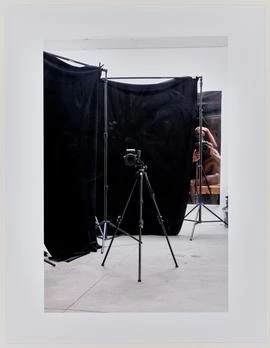

this photographer came daily to a spot

beside the Bristol Channel, looked across it

towards the coast of Wales and made a picture,

and went on making them day after day,

week after week, month after month, two years.

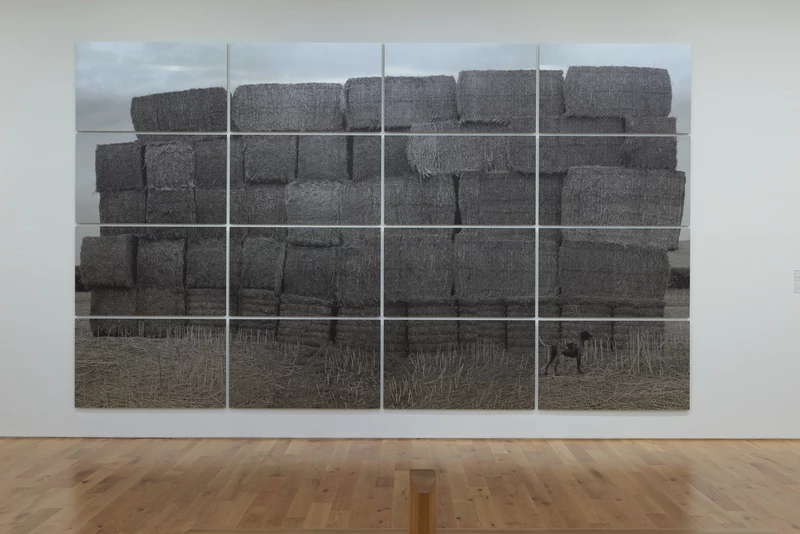

From all these studies, each with the horizon

parting its square into matched rectangles,

he’s chosen a selection, which is hanging

in this spacious room in the museum

in Cardiff, so that we can move between them

and seem to see and – not to understand

but – to open up a little better

to the always-ungraspable reflected

in the subtly shifting clouds and waters,

with the straight outer edges of the pictures

and the reassuring recurrence also

of the not quite straight, never-the-same-twice

horizon always in the same position,

enabling us by contrast to be more

open to what is forever changing.

Among the aids to better meditation,

that state that seems to offer the profoundest

and sweetest possibility of living,

along with music, poetry and painting,

yoga, Qigong, monastic prayer and fasting,

this suite of photographs makes an addition.

John Freeman’s poems have appeared in many magazines and anthologies, and in twelve full collections, the latest of which is Plato’s Peach (Worple Press). His most recent book is a collaboration with photographer Chris Humphrey, Visions of Llandaff (The Lonely Press). He lives in the Vale of Glamorgan and taught for many years at Cardiff University.

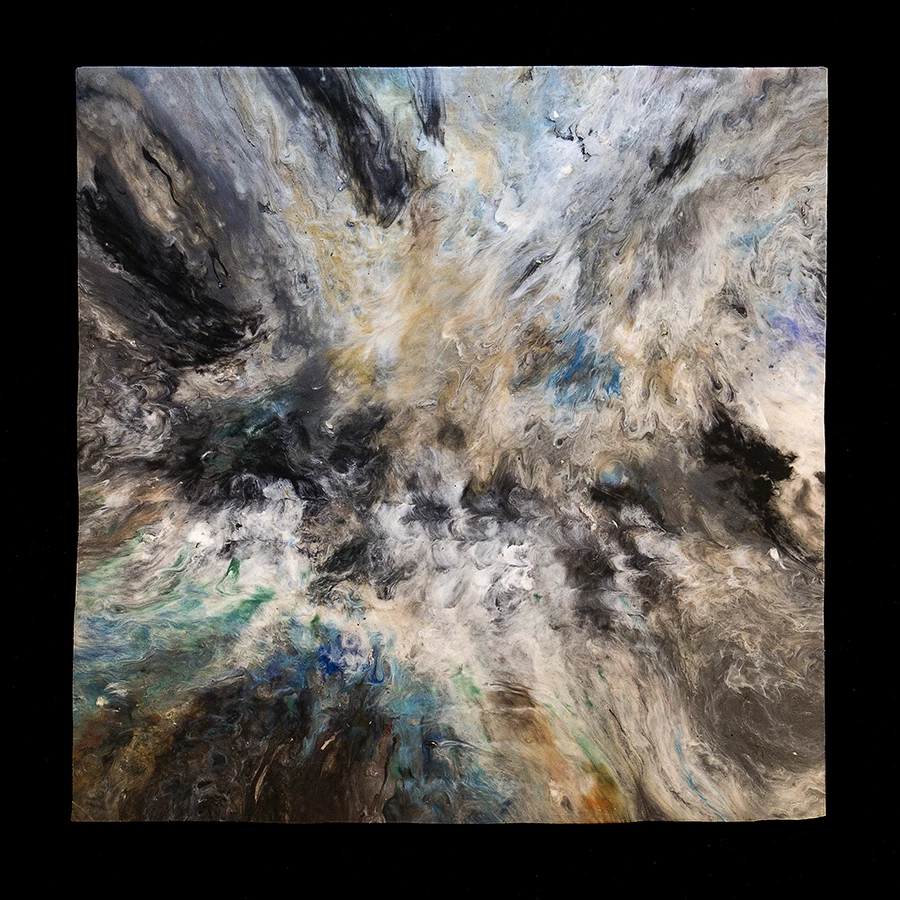

Garry Fabian Miller

The Sea Horizon, No. 18, 1976–77

© Garry Fabian Miller