Any large art collection amassed over decades will have a multitude of different stories within it. These can be stories around an artist, a person in a portrait or the collector who donated an artwork to the Museum. A national collection of art is no different and carries with it additional layers of history – what does a collection of art say to us about the country we live in; its past, present and future? Museum collections can tell us a lot about ourselves and they also reflect societies of the past. One of our jobs as curators of that collection is to tease out these stories and to relate them to the world that we live in today

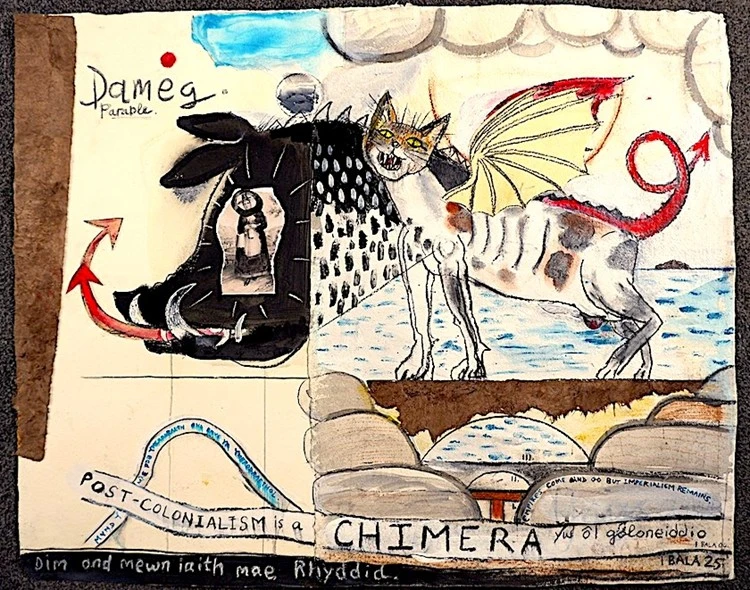

The Rules of Art?, held at National Museum Cardiff between October 2021 and June 2023, takes a broad view across half a millennia of the art collection. Amgueddfa Cymru has one of the finest art collections in Europe, and this exhibition is ultimately about celebrating and showcasing that collection in a new way. This will create new relationships and spark a variety of questions around who the collection represents, who it does not and why.

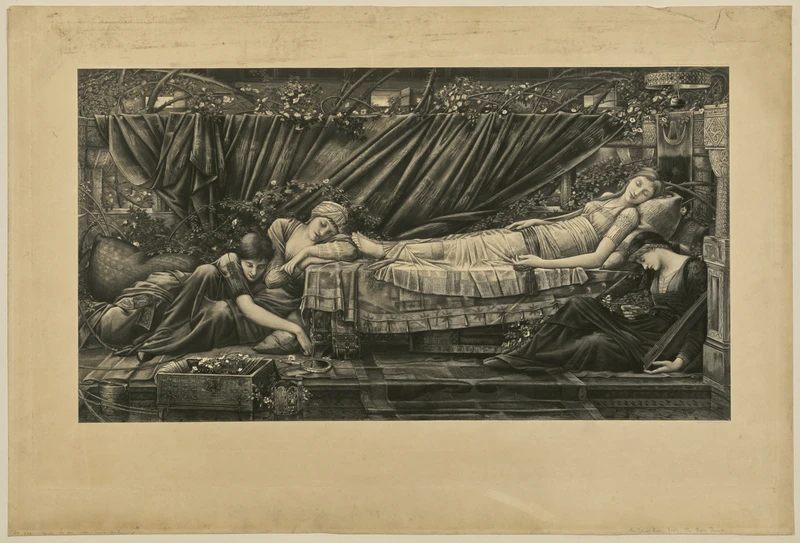

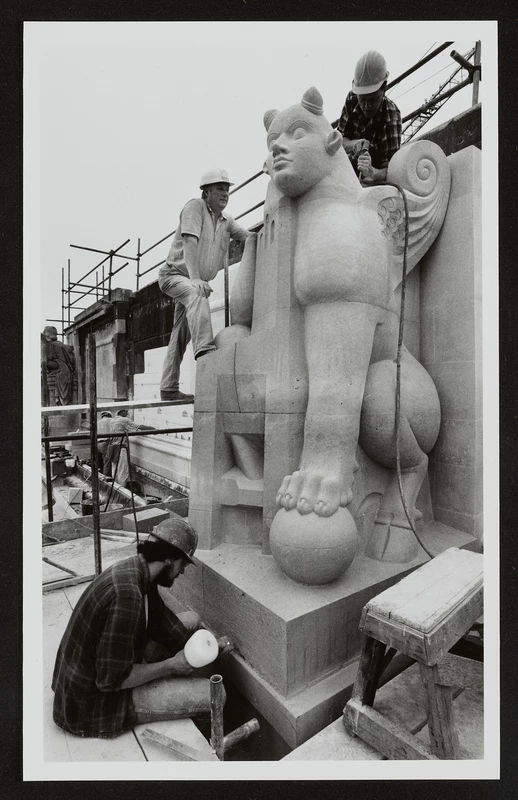

The way that museums have showcased their collections has, particularly historically, followed a largely chronological path. Paintings and sculpture were shown within their respective stylistic or geographic ‘schools’, forming an official timeline of art. This can be a very useful way to gain an understanding of movements within art history, but it can give a narrow view and exclude many artists that aren’t seen to fit within a particular area. Also, it can give the false impression of a unified progression; that art always moves forward, one style informs and gives way to another. This is not the case; the progression of visual art has been fractious and it has ebbed and flowed. An example I often think of is between two hugely important sculptures of the early 20th century: Rodin’s The Kiss (1901–1904) and Jacob Epstein’s The Rock Drill (1913–1915). Looking at these two works within their respective ‘schools’ or geographies, they look as though they could easily be separated by centuries when it is, in fact, less than a decade. Grouping things together can neatly emphasise similarity, but it can also ignore diversity.

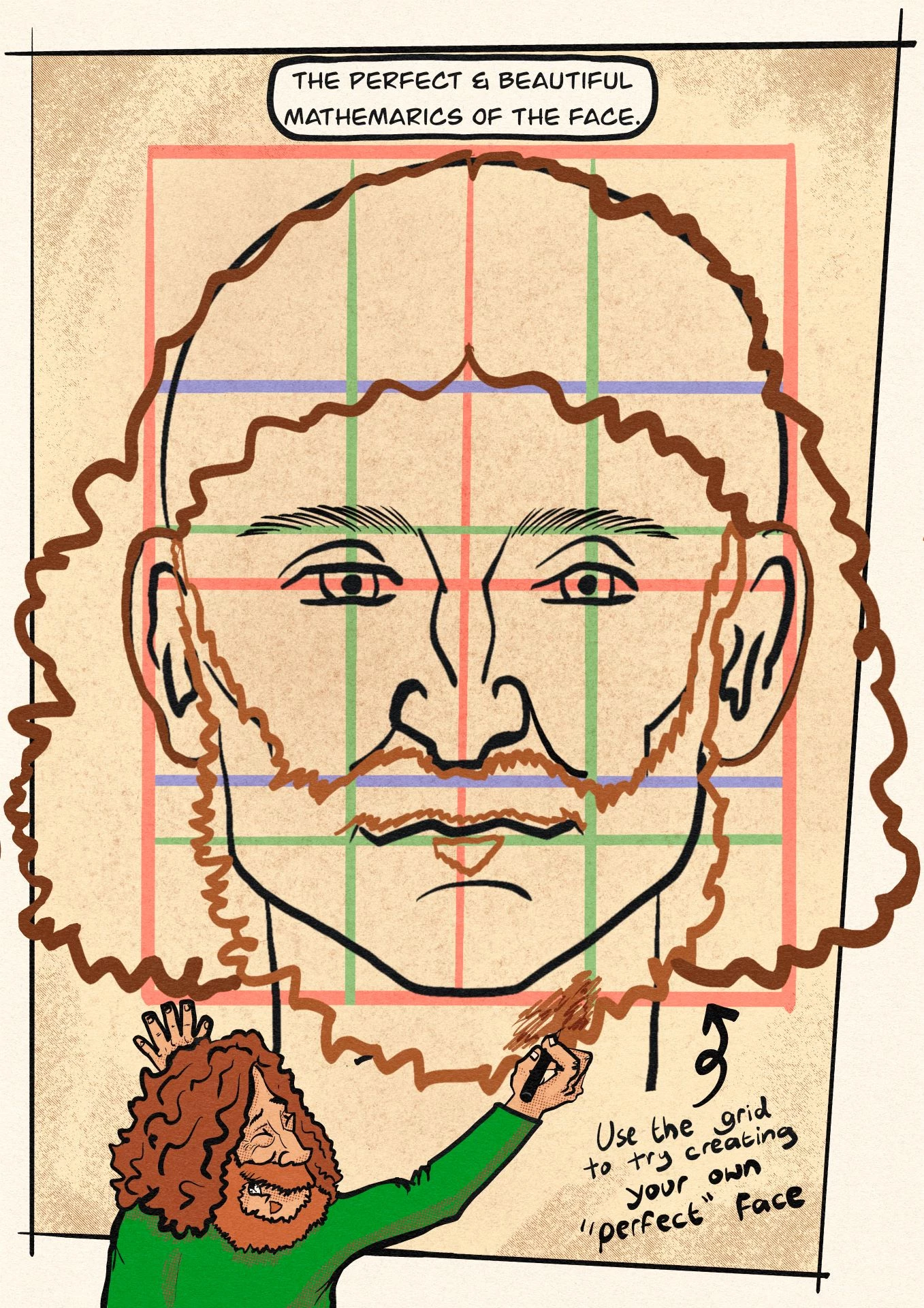

Teaching Art: A complex history

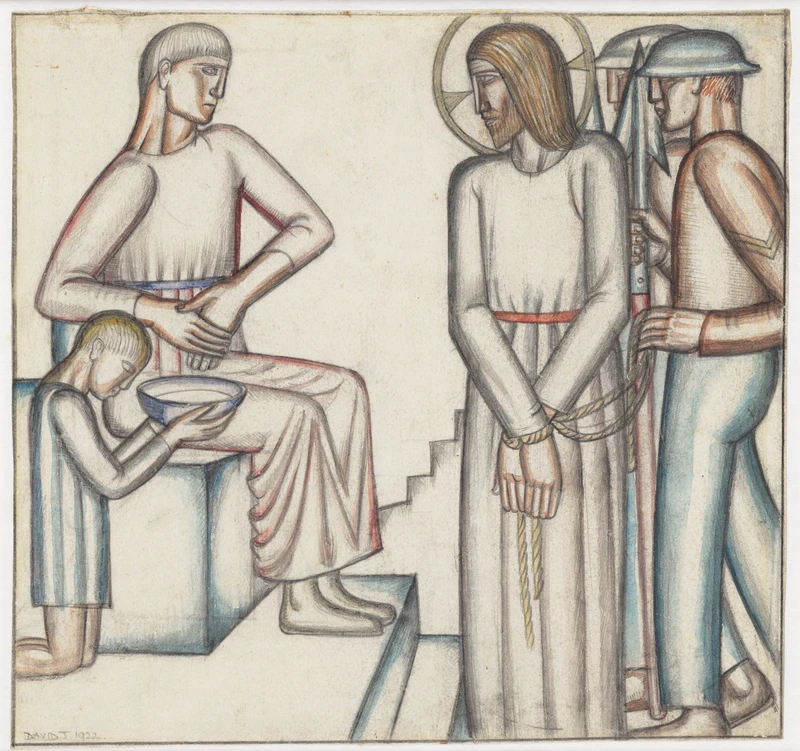

The way art was taught has been even more rigid. In 1669, Andre Felibien, the French writer and Secretary to the French Academy, set out the principles of painting that formed what we now refer to as the Hierarchy of Genres. This hierarchy places a particular type of painting over another, formalising thought in Western art that dates back to the Renaissance. For example, paintings of biblical scenes or portraits of nobility were placed higher than still-life paintings. The hierarchy is:

- History Painting

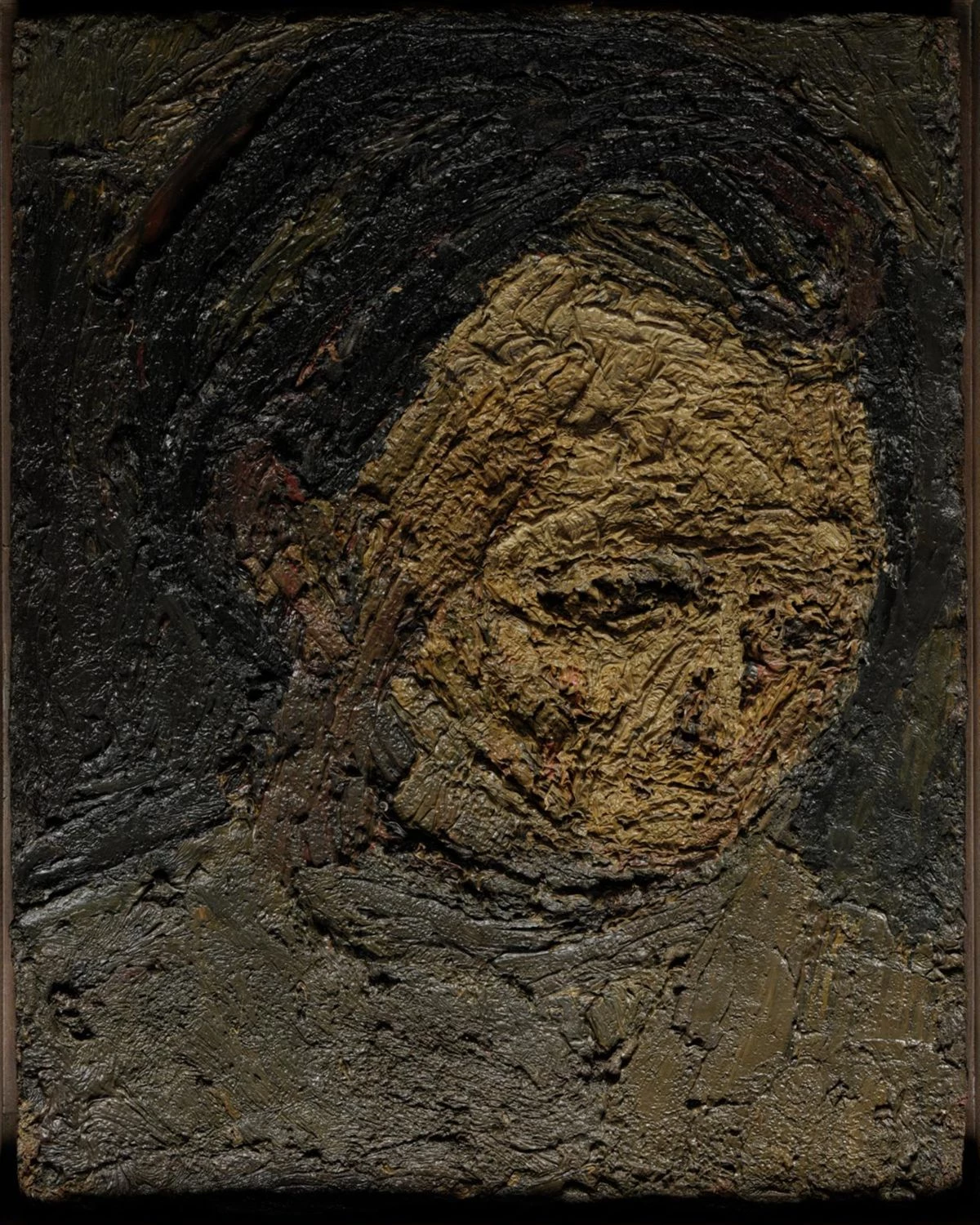

- Portraiture

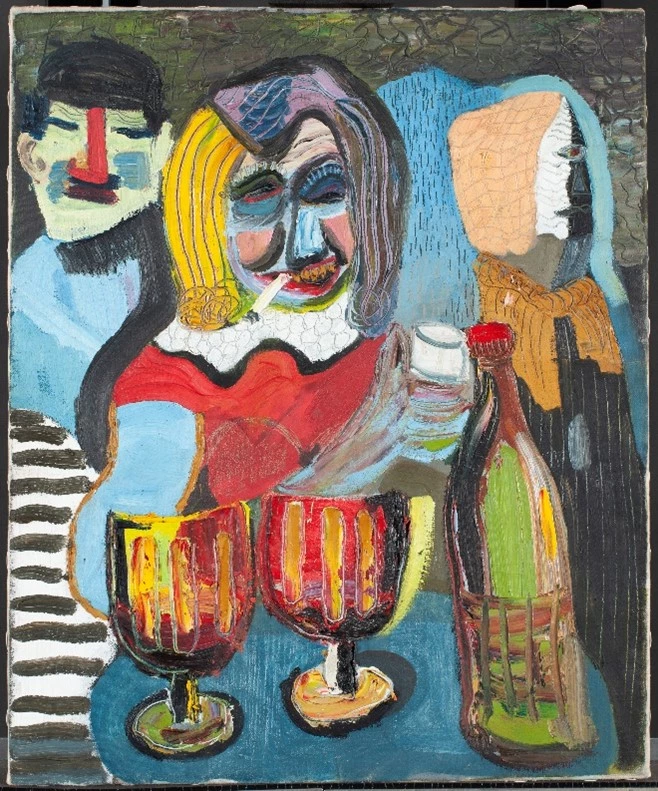

- Scenes of Everyday Life

- Landscapes

- Still Life

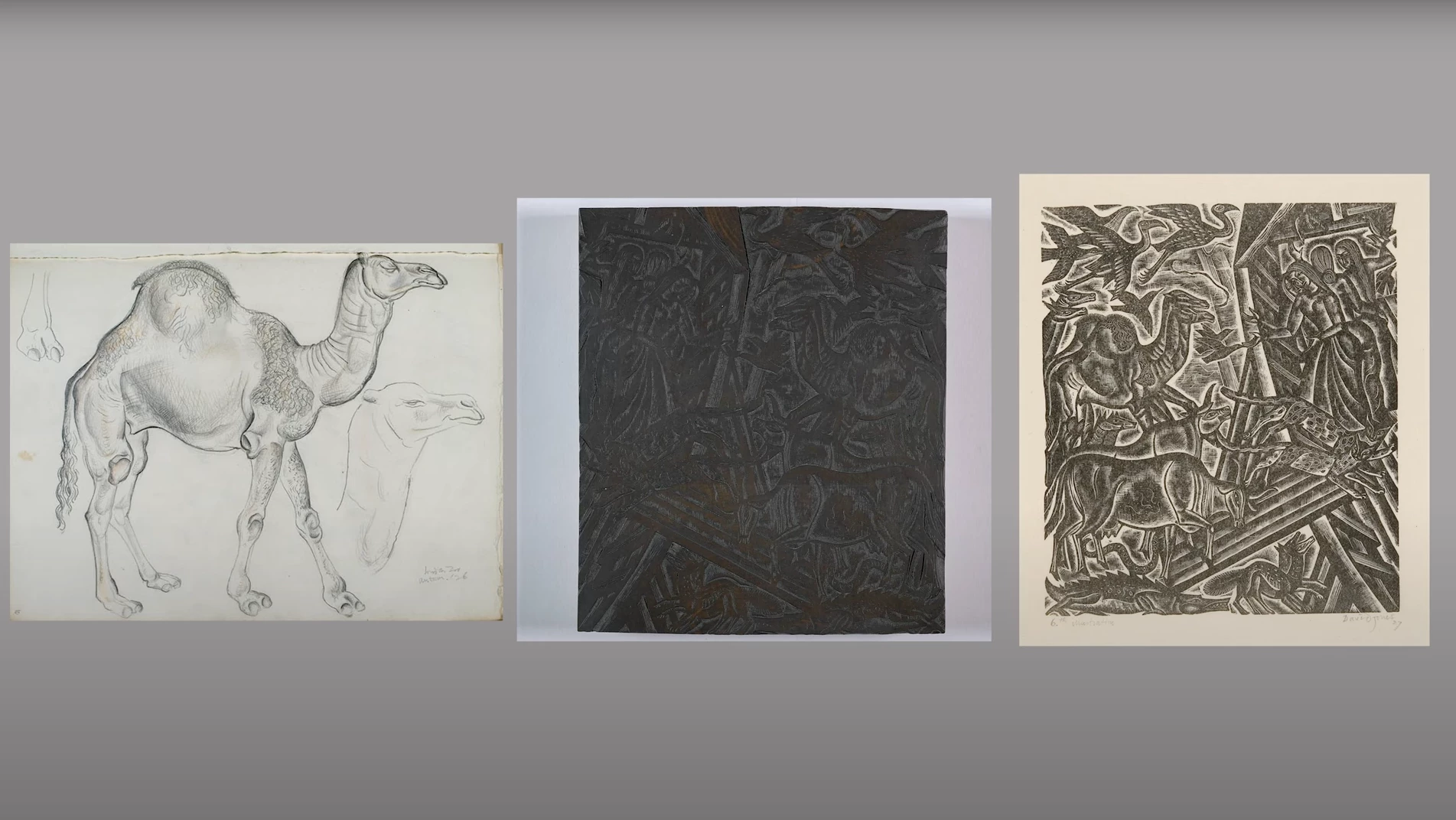

For hundreds of years, art was taught within this system, with it only really changing as we moved through the 20th century. It was therefore in an artist’s interest to create work that fitted within this prescriptive ‘league’, as more money and status was available to those artists making paintings that sat at the top of that hierarchy.

For centuries this dictated what artists produced, what collectors bought and – ultimately – what museums have collected. It has had a profound impact on the collections that we see in museums to this day and has reflected and reinforced wider societal power structures. The world that a museum reflects back at us is not always the world as we experience it.

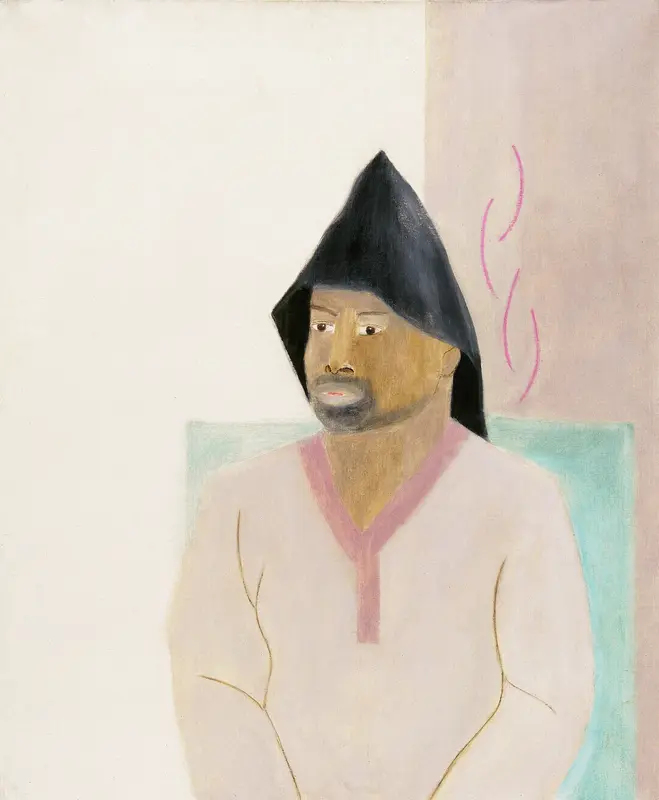

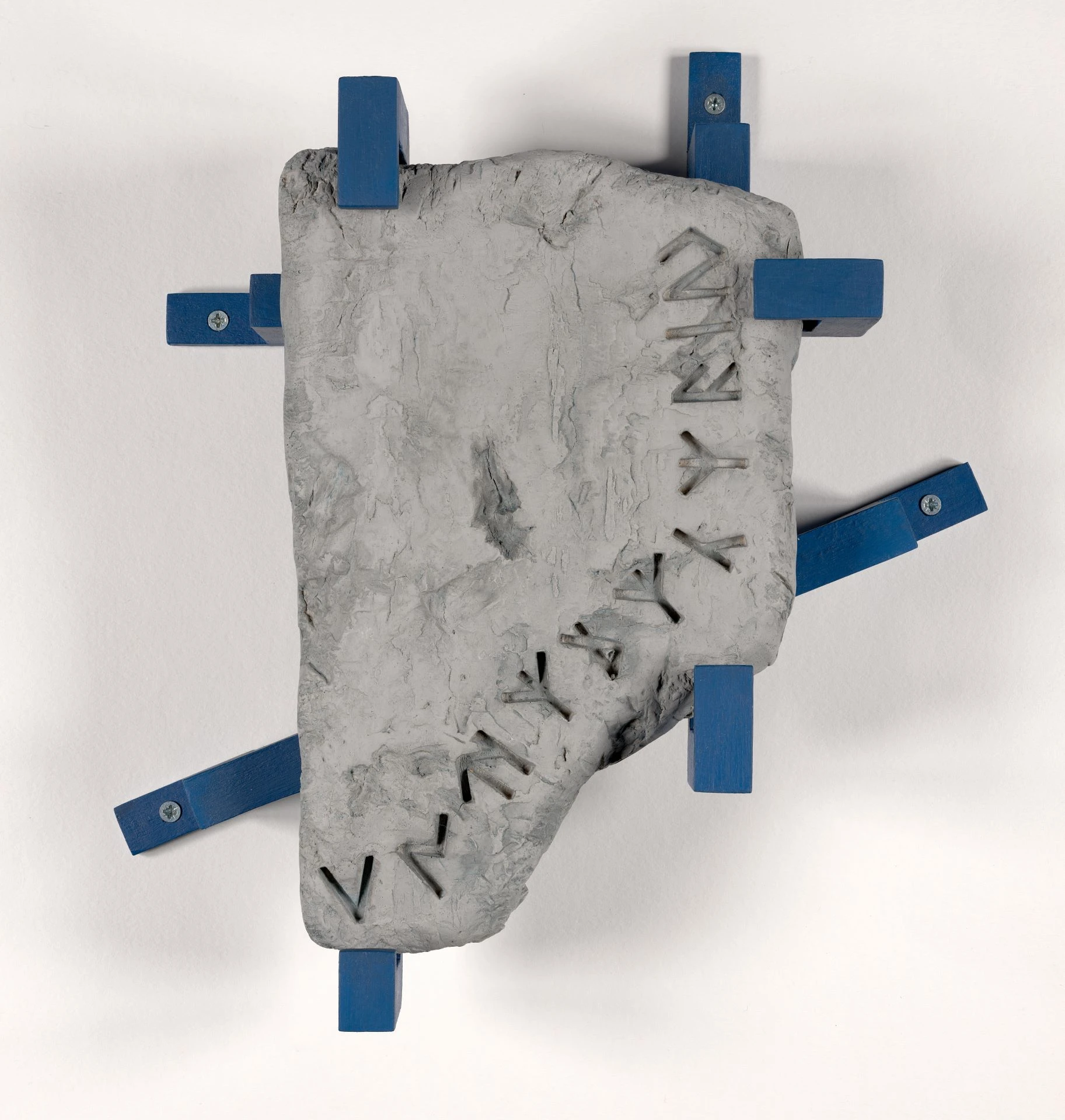

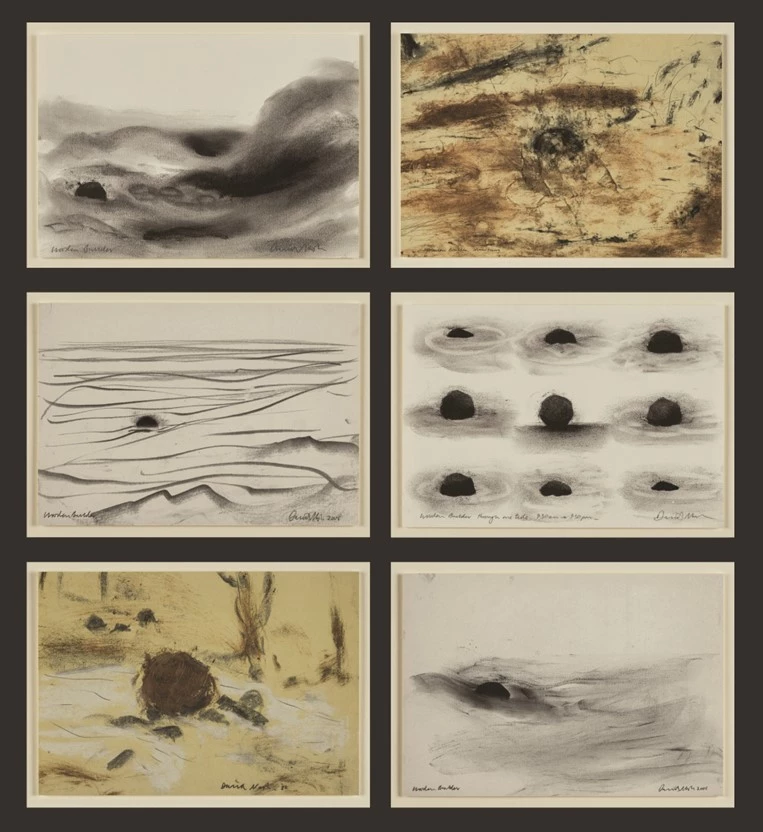

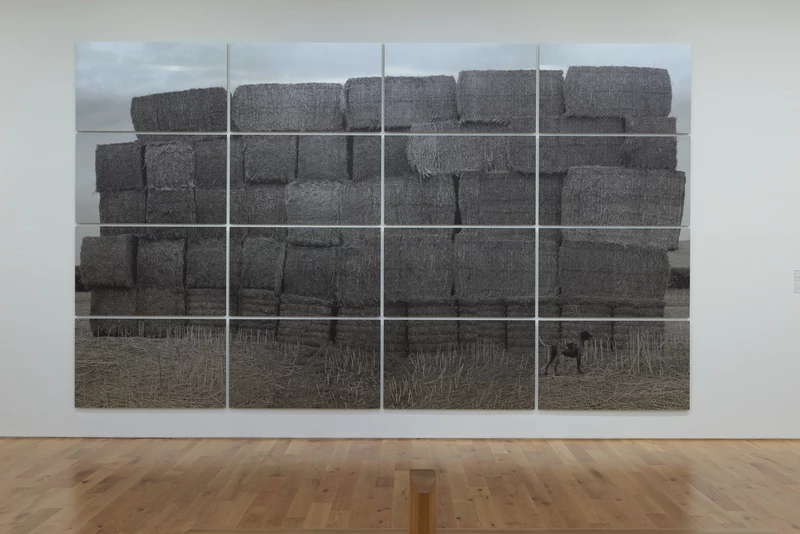

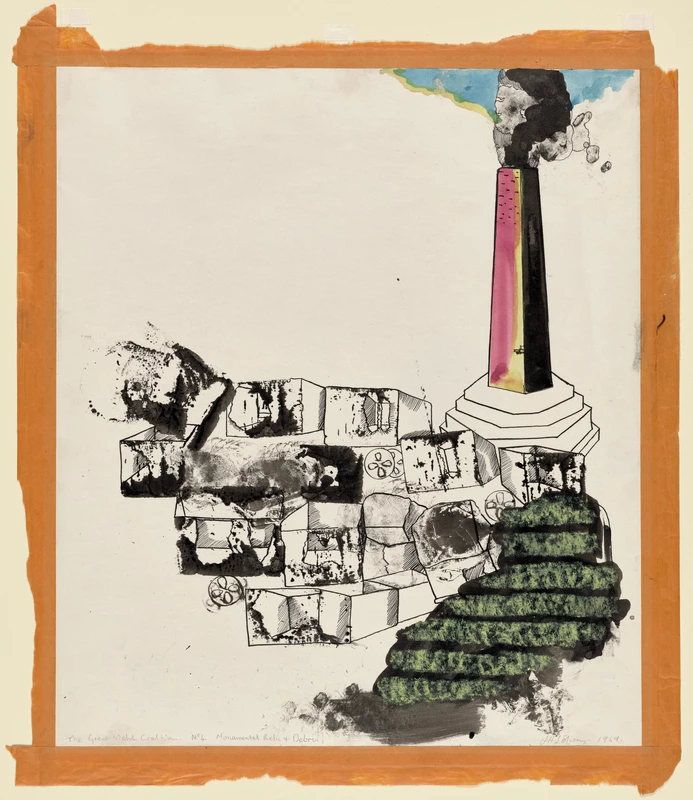

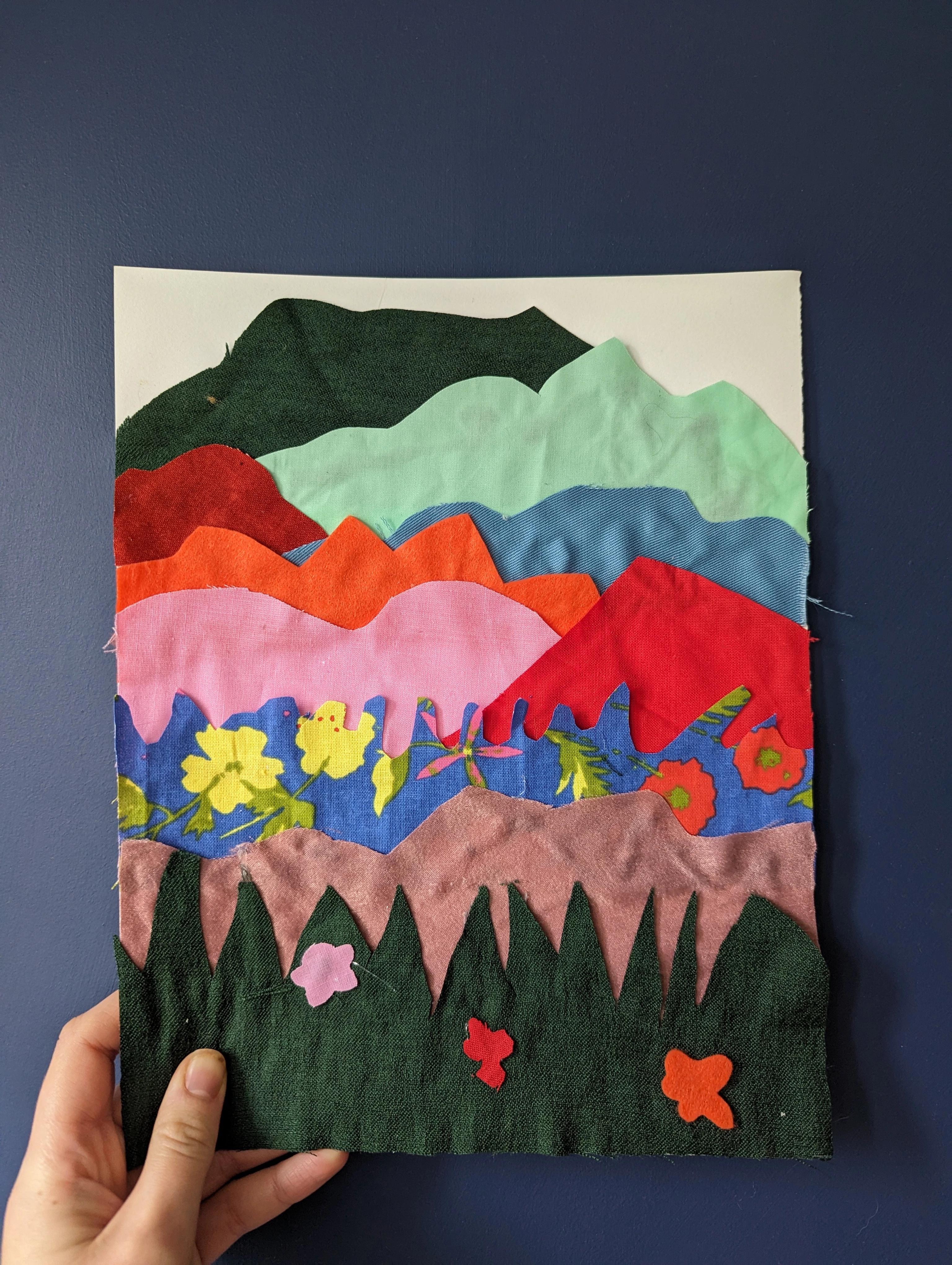

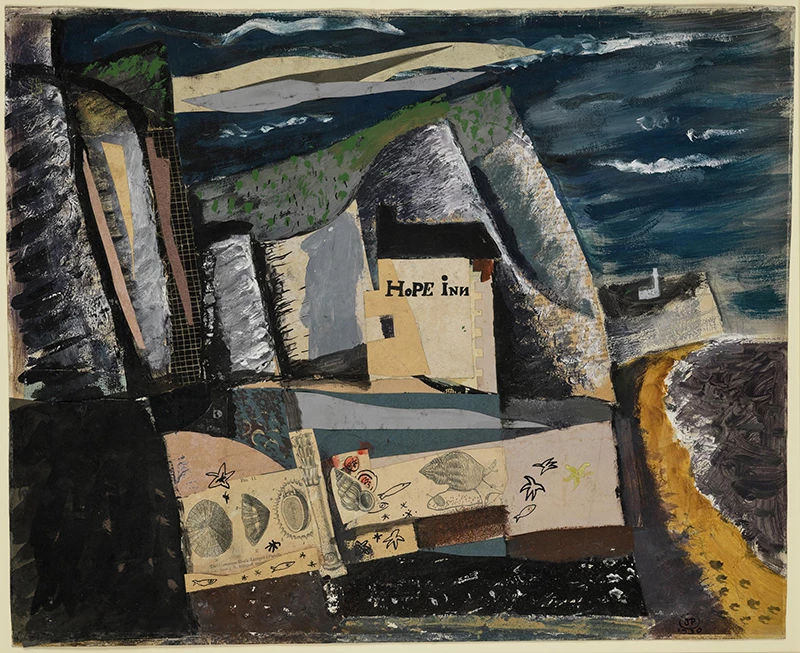

Therefore, The Rules of Art? used this same hierarchy of genres to show our collection in a different way; not chronologically or by ‘school’ but by theme. This allowed us to explore new relationships within the collection; to display Historic and Contemporary art works which had never been shown together before. Questioning the hierarchy itself was as important, showing the artists who have questioned it and revolutionised how we think about art today. The work of the Impressionists was so controversial in 19th century France, for example, because it flagrantly went against the perceived wisdom of the French Academy.

Showing what’s missing

Showing the collection in this way also highlighted absence, although curatorially this is much more challenging to achieve. Like many large collections of art around the world, ours reflects a very particular history and does not always reflect the world we live in today. Looking at and understanding those absences is a really interesting way to not only interpret our historic collections, but also to imagine what our collection should look like in the future.

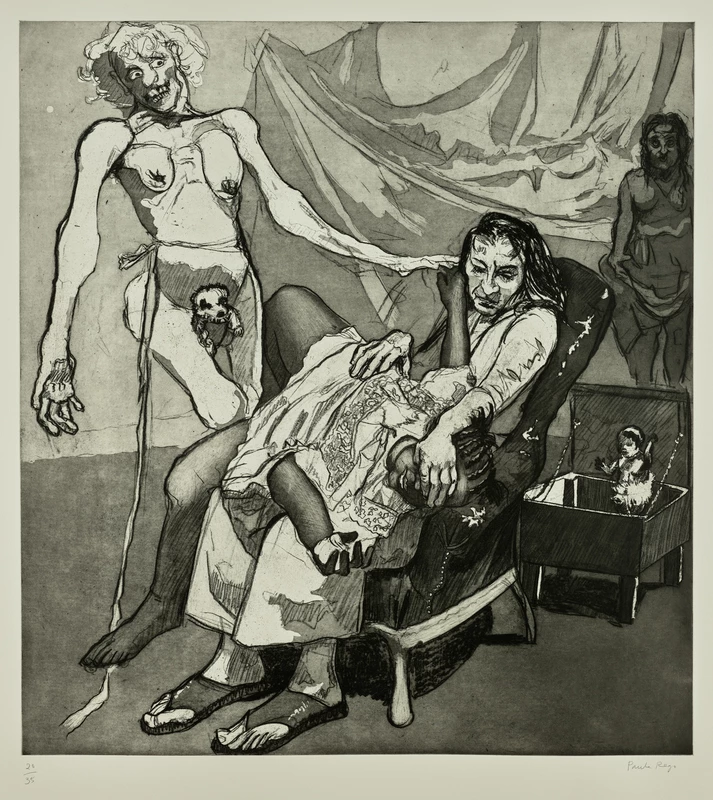

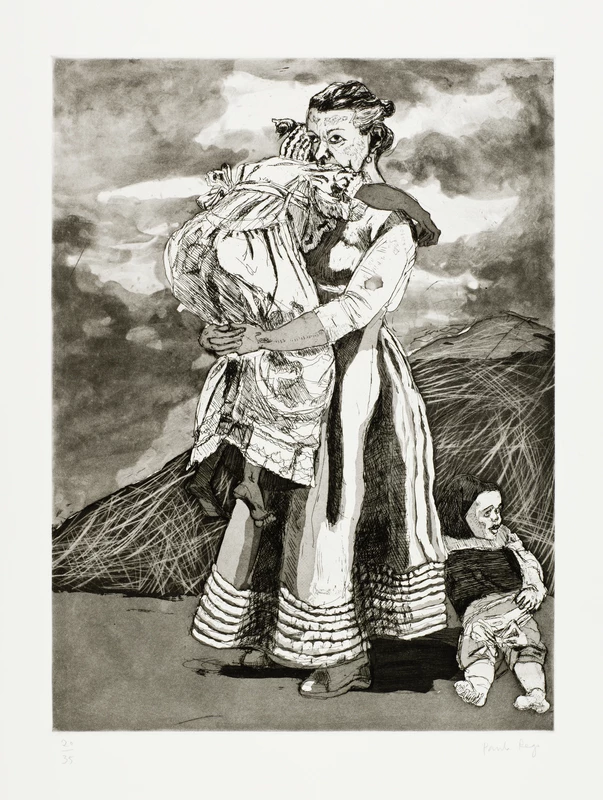

An important example of this is the representation of women artists. As with many other museums, there are very few women artists in our collection prior to the 20th century. One of the reasons for this is that women were denied formal art training at Art Academies around Europe until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Academies were one of the most prestigious ways for an artist to receive formal training, to showcase their work and therefore gain sales and commissions. Women were not just disadvantaged by the system, but were completely excluded from it. The Rules of Art? shows artists such as Gwen John, who were at the vanguard of women art students. The exhibition also celebrates the work of artists, like the photographer Mary Dillwyn, who created art despite societal hurdles put in their way.

Starting conversations

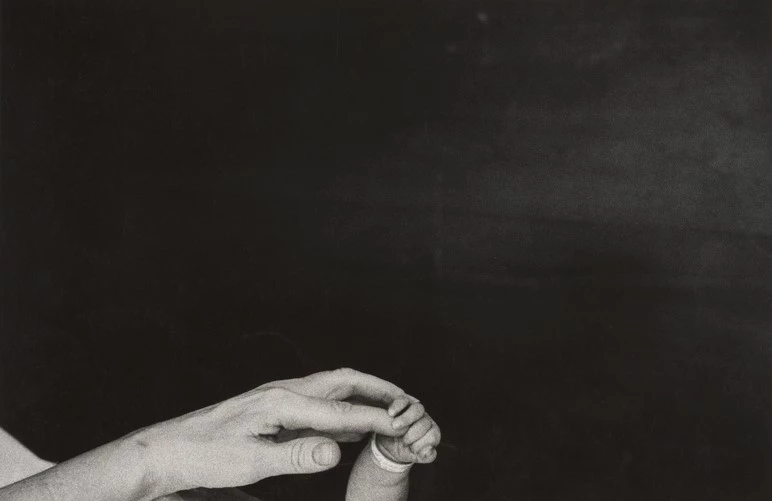

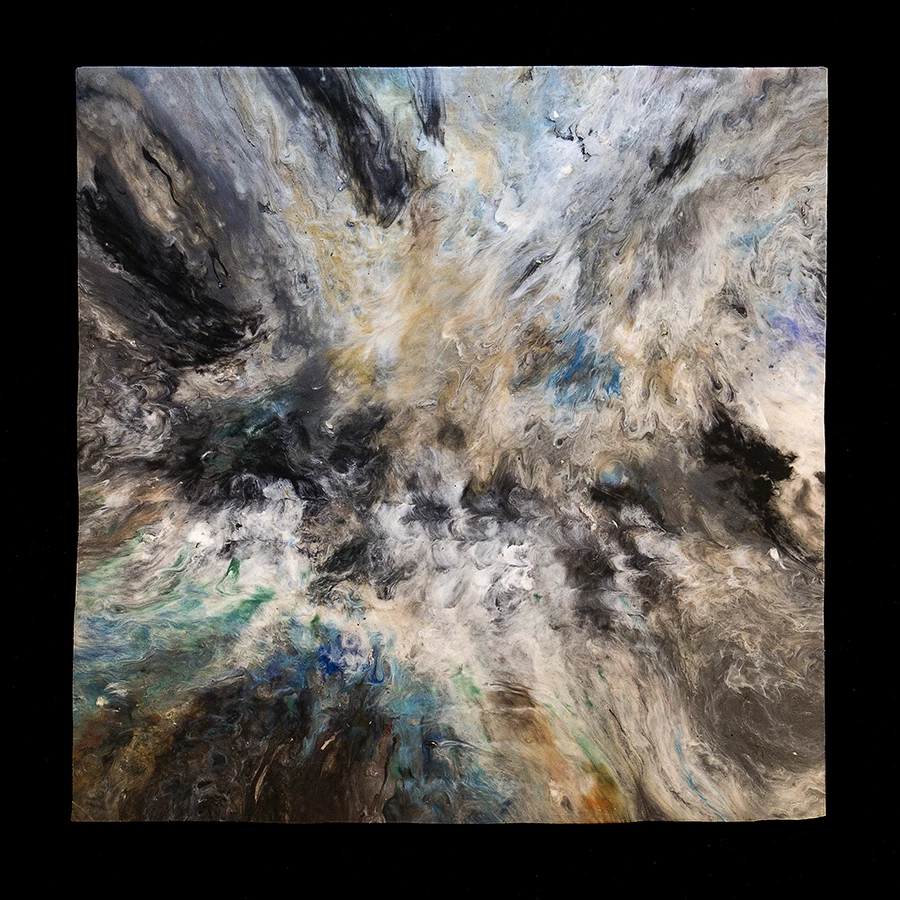

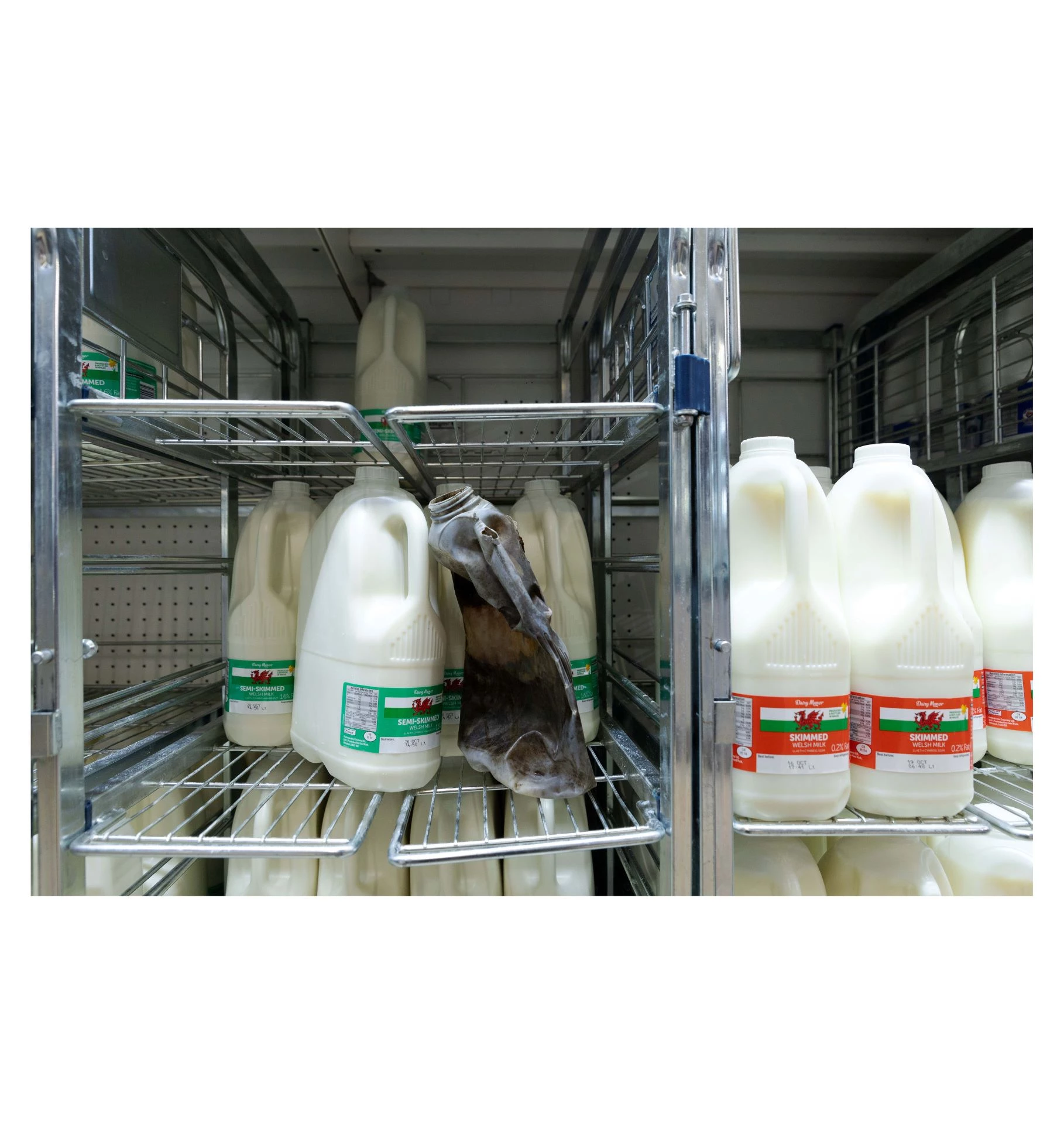

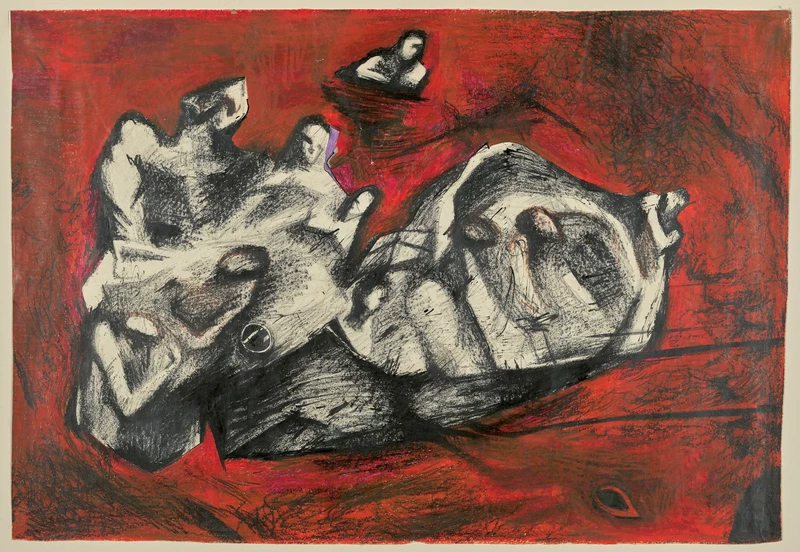

The exhibition culminates with John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea (2015) – a new acquisition to our contemporary collection, purchased in partnership with the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne. This three-screen video encapsulates many of the themes addressed in the rest of the exhibition, and much more besides. It explores the beauty of nature and the destruction wrought by humans to the environment and to ourselves.

The work draws on a wide range of visual and literary sources, incorporating new footage and the BBC Natural History archive. It is dizzying in scope and presentation; Akomfrah explores a broad sweep of human history and the three screens of the film surround you, filling your vision. The whaling industry, the current refugee crisis and the transatlantic slave trade are among some of the themes addressed. Peppered throughout the film is the personal narrative of Olaudah Equiano (1745–1797), a former slave and abolitionist. At its heart, Vertigo Sea also embodies the notion of the sublime – the mixed sensations of beauty, awe and terror inspired in us by the natural world. This has fascinated artists for hundreds of years and, in our current climate emergency, is something that is all too relevant today.

More than anything, The Rules of Art? is the start of a conversation, rather than the end of one. Our audiences are a vital part of this conversation, and in shaping how our collections are displayed now and in the future.