A recording of this article narrated by the author Tina Rogers is available via YouTube.

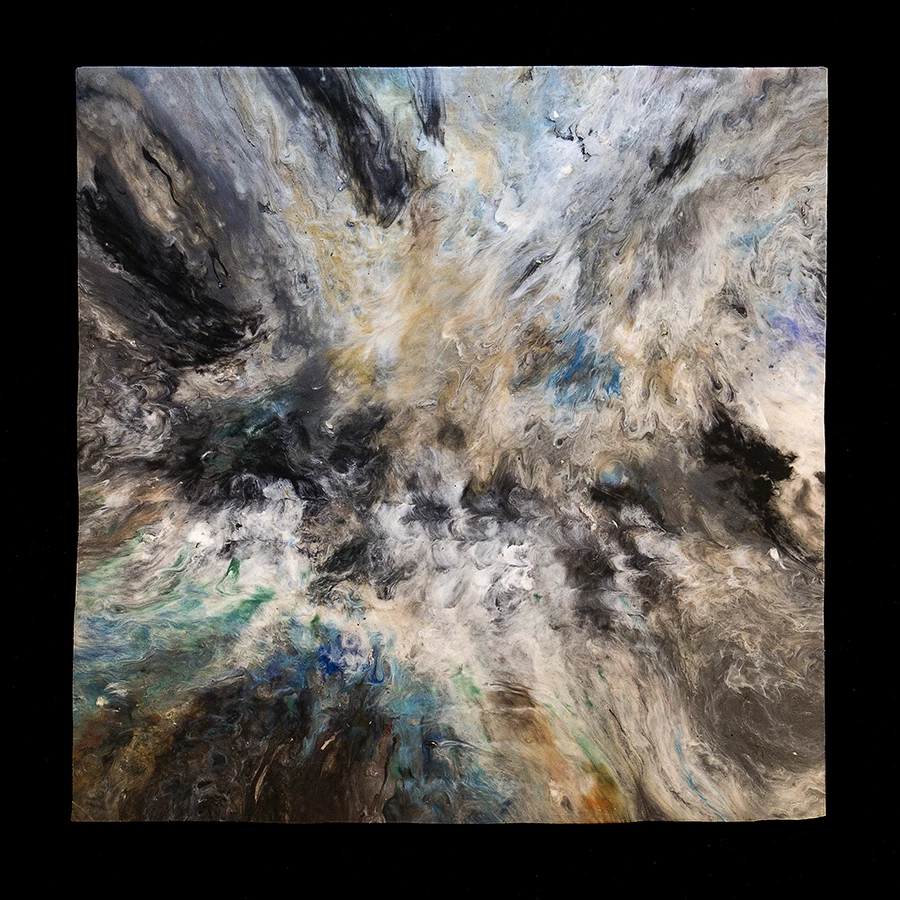

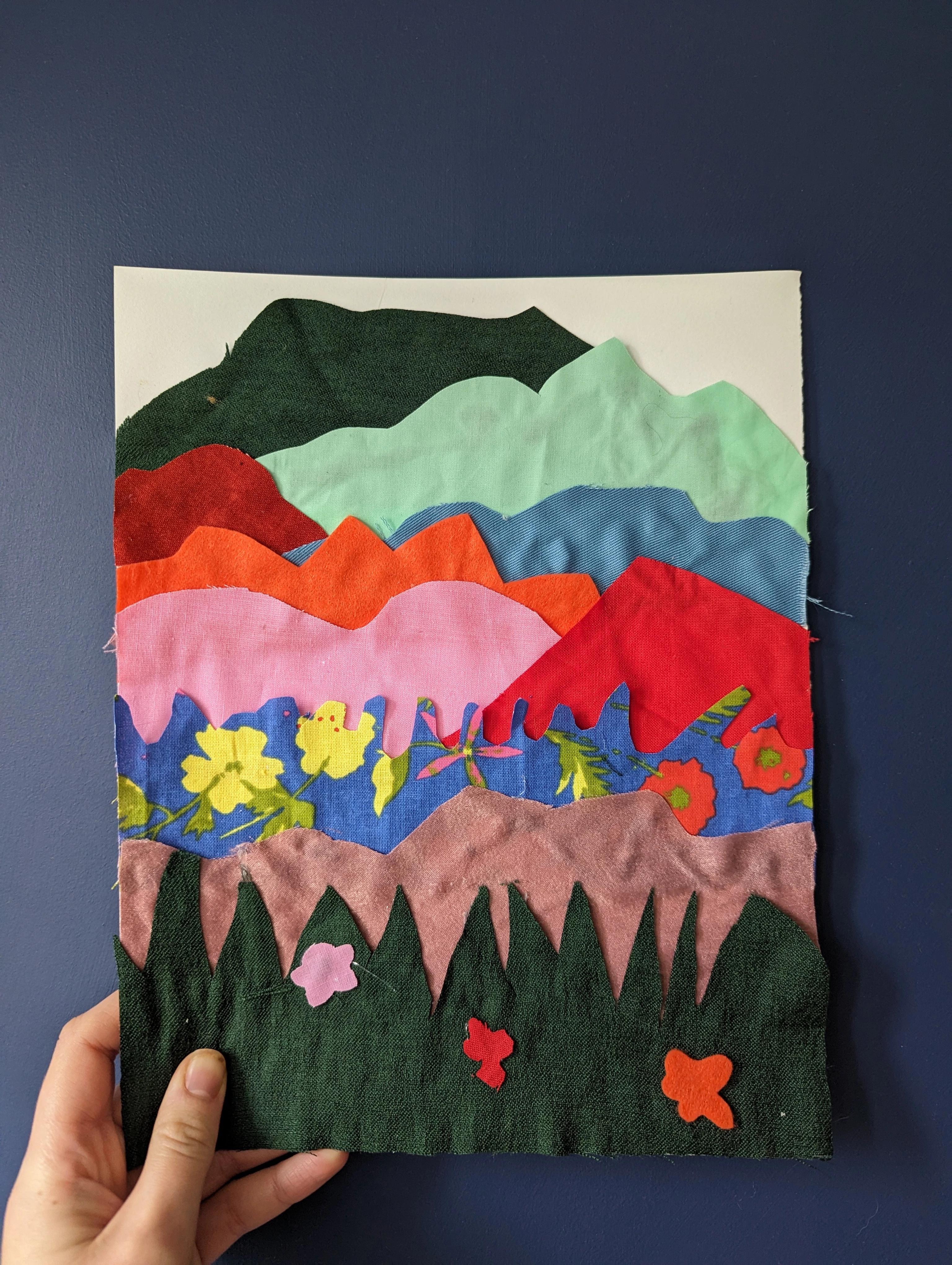

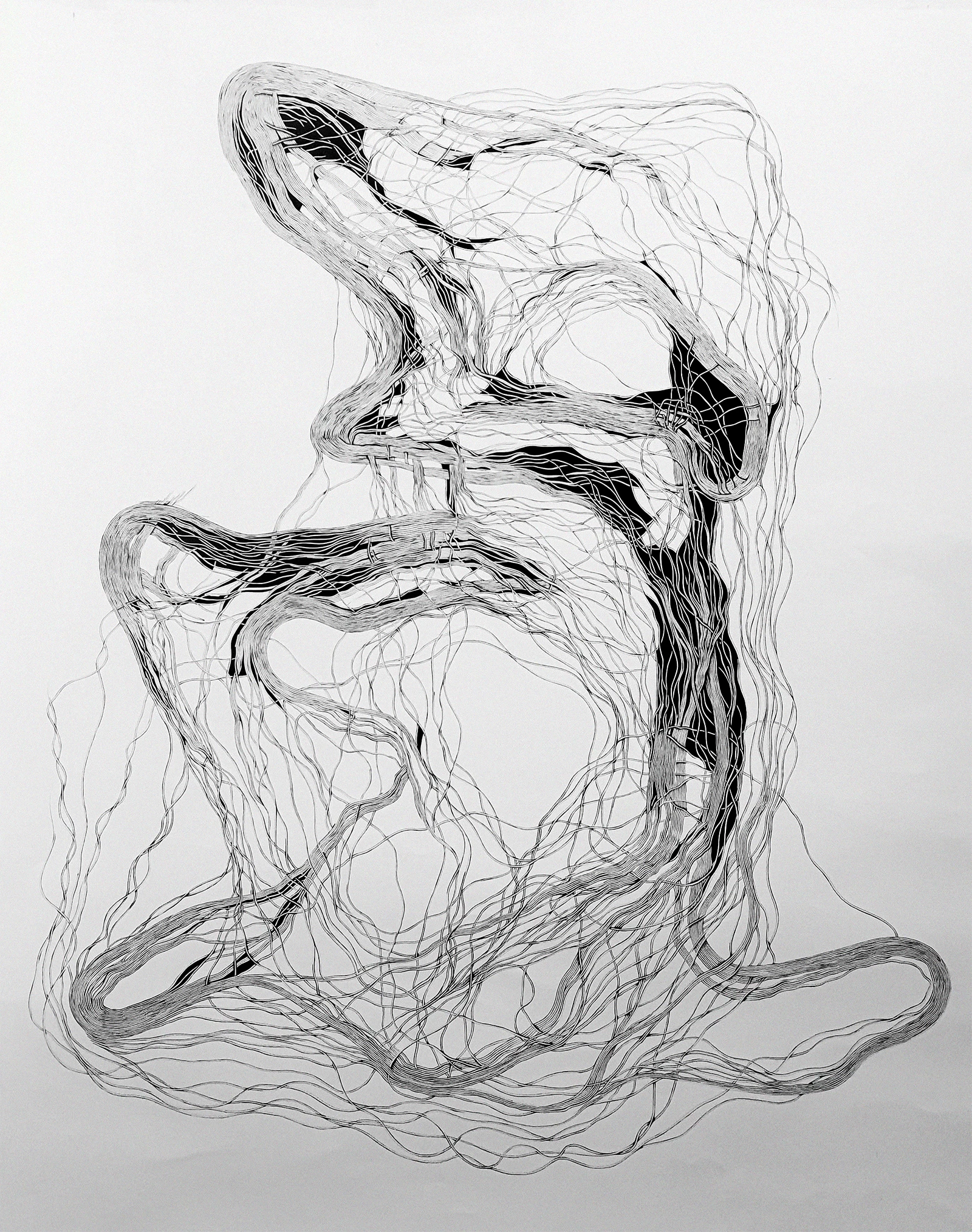

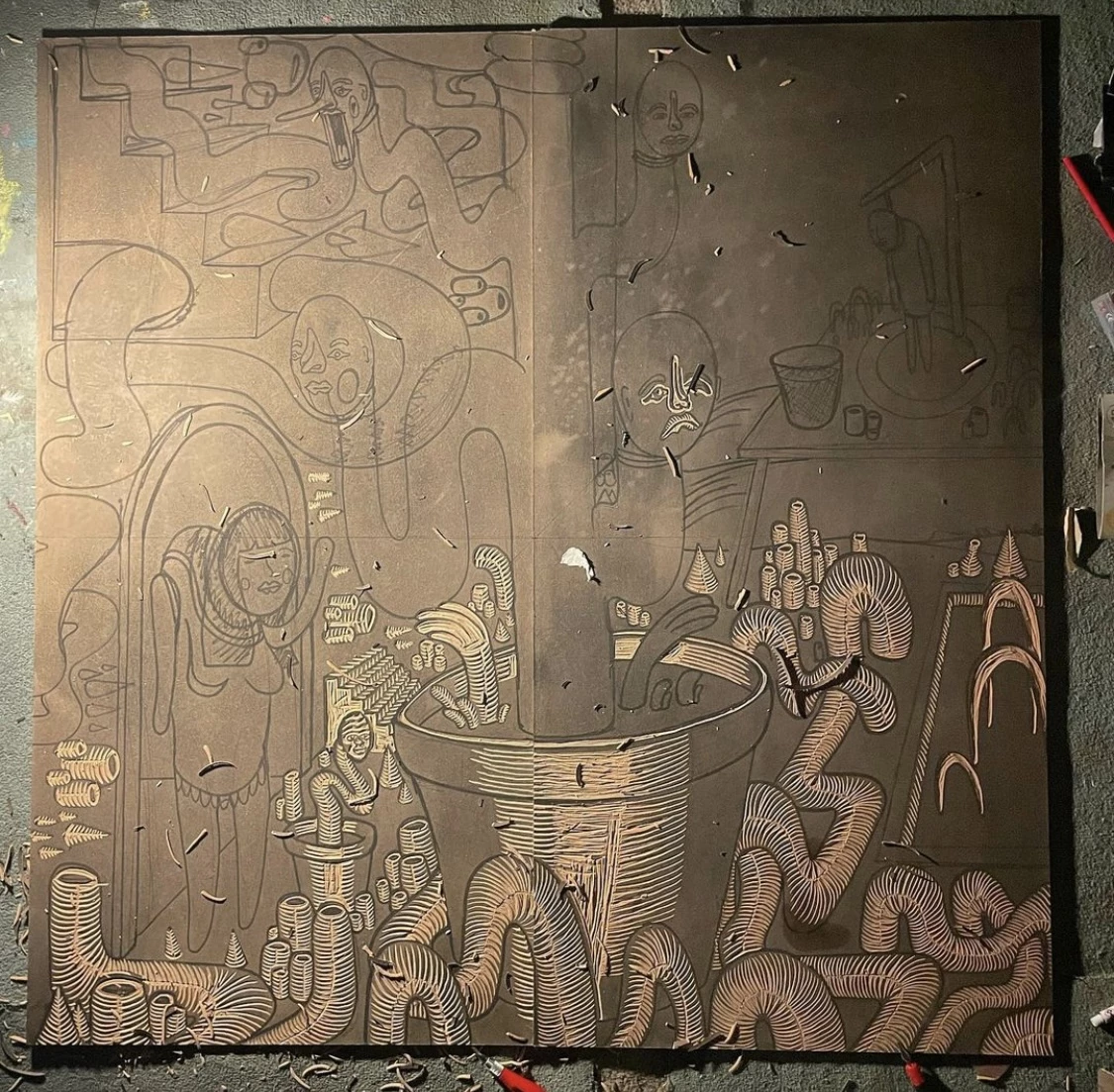

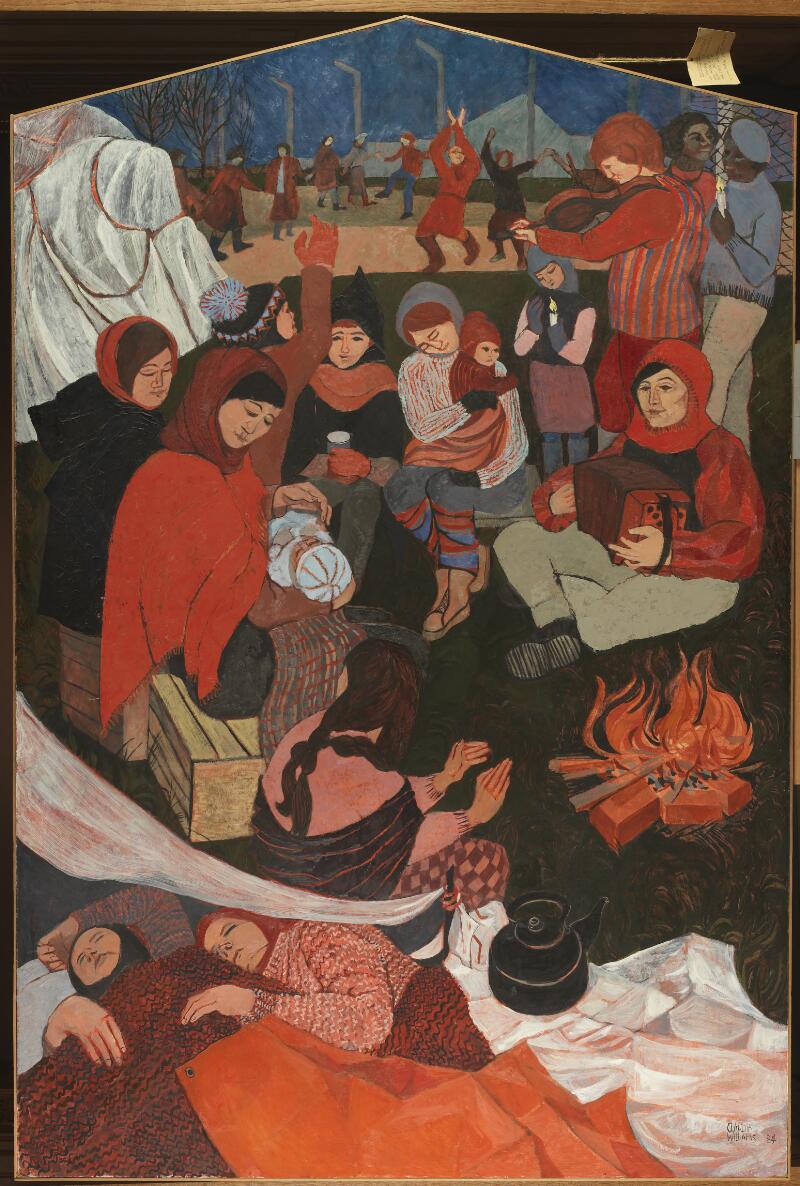

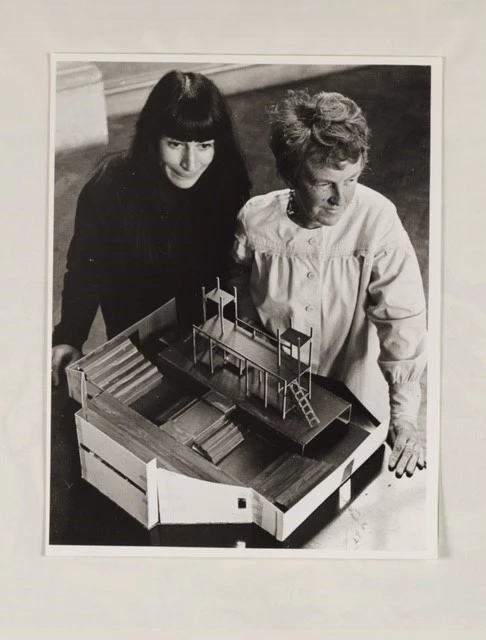

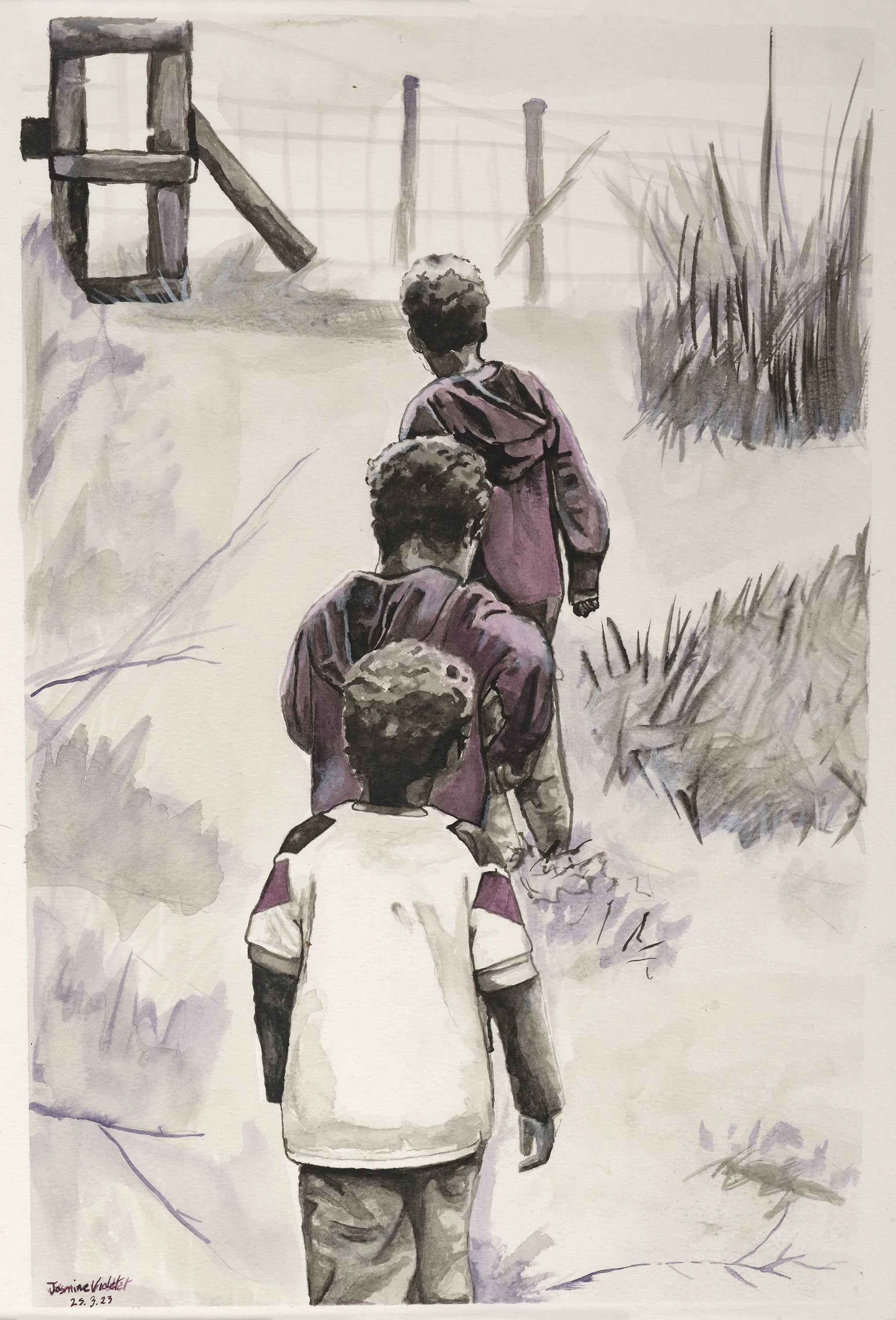

ROGERS, Tina. Painting & Collage of the Ladies of Llangollen. ‘The Power of Two’ © Tina Rogers

Everyone who lives in the surrounding area of Llangollen knows about the Two Ladies who lived at Plas Newydd – Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler.

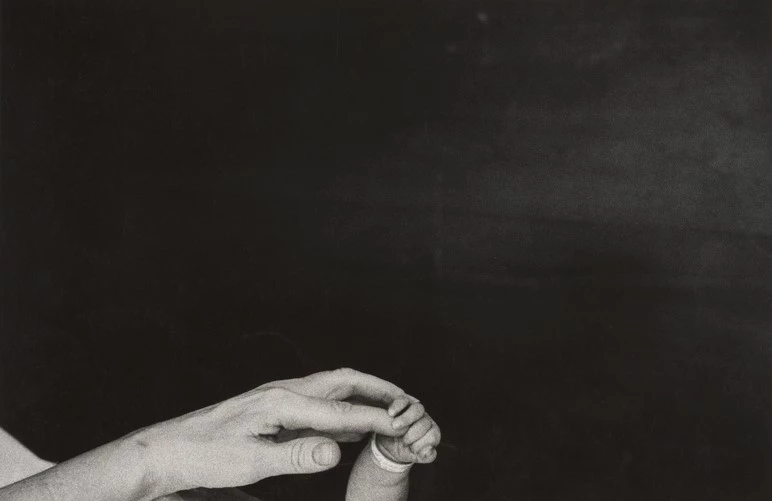

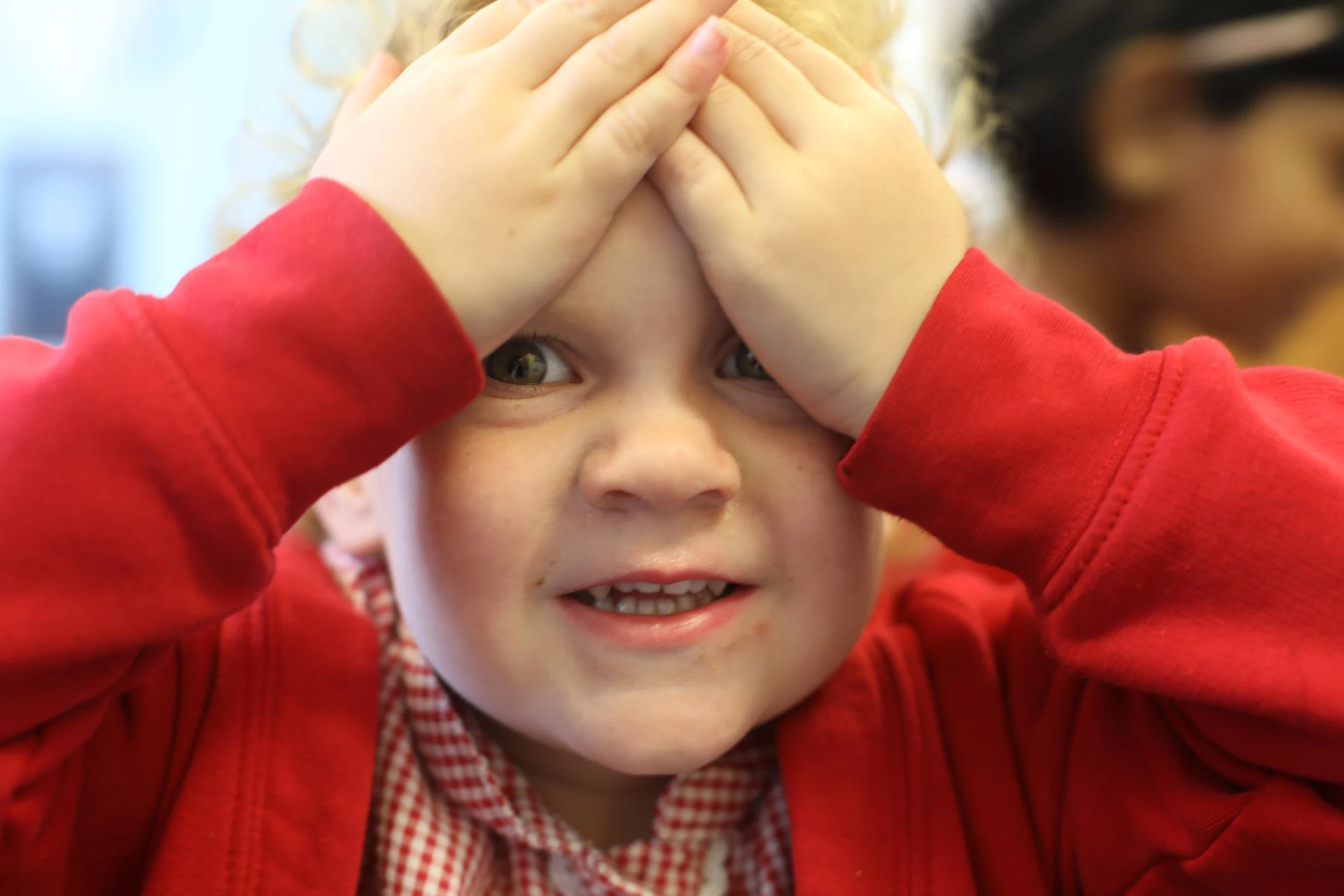

ROGERS, Tina (1977) Photo of Tina aged 13 with her baby sister Jennie and Nanna Susie

My own connection to these Ladies started with my Northern Irish Nain (grandmother) who landed in Llangollen in 1947 and never left. Even though I lived 5 miles away in Chirk, during the summer I would be dropped off for an excruciating ‘holiday with Nanna Susie’.

My memories of those visits consist of three things, a pervading sickly-sweet smell of day-out-at-Rhyl bought ‘Lily of the valley’, the amazing knitted doll that concealed a medicated paper toilet roll in her vibrant pink bathroom, and our daily trek to Plas Newydd to pay homage to ‘The Ladies’.

On asking my Nain who they were, and why did we have to keep trekking up to their house, I was told to ‘shush’. It’s only as an adult that I realise my grandmother was as much in the dark about these two women as I was, and the daily visit was just something to do.

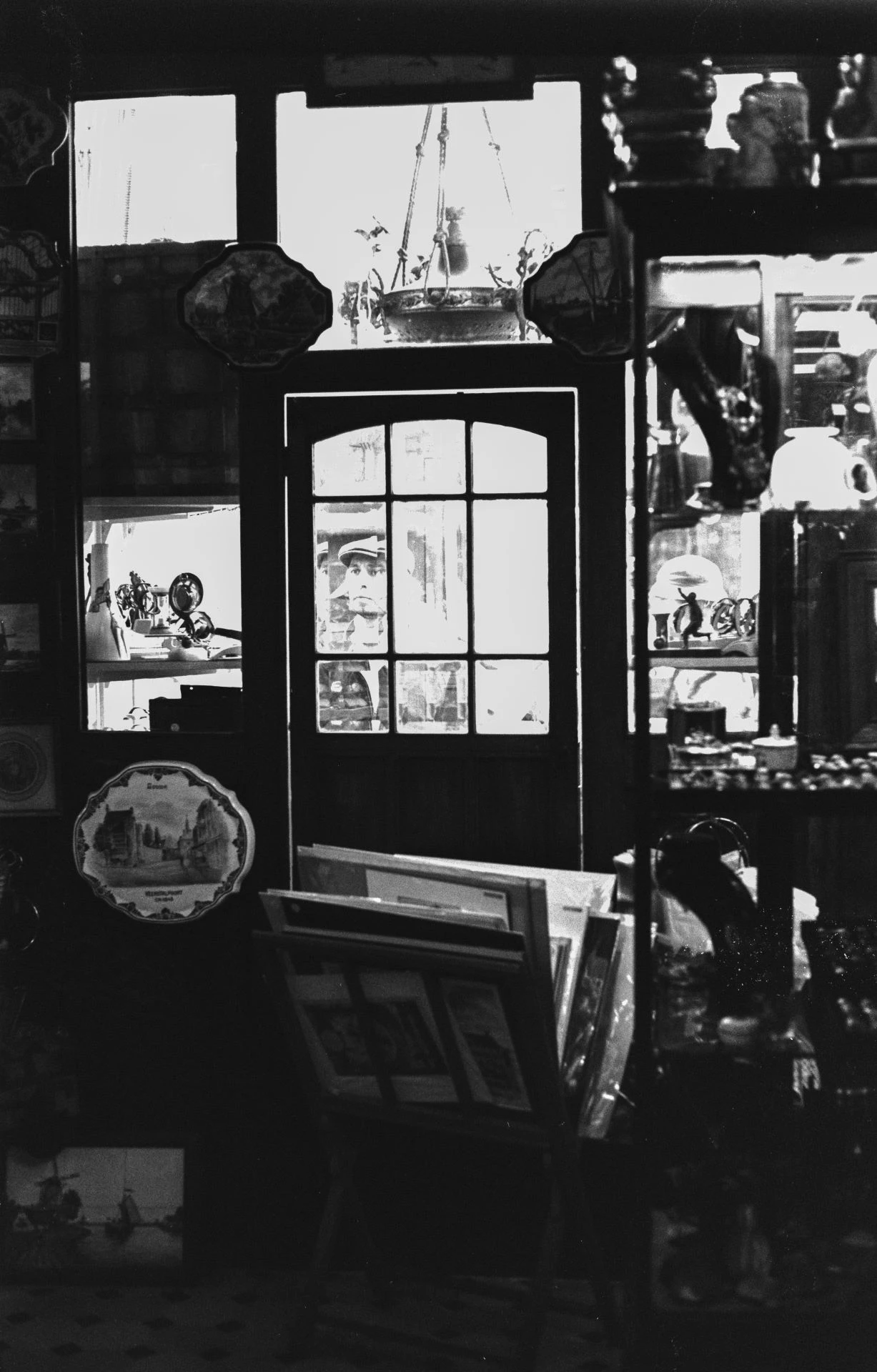

The doors of Plas Newydd, Plas Newydd House Museum and Tearooms, All You Need to Know Before You Go (2024)

Accessed: November 2024

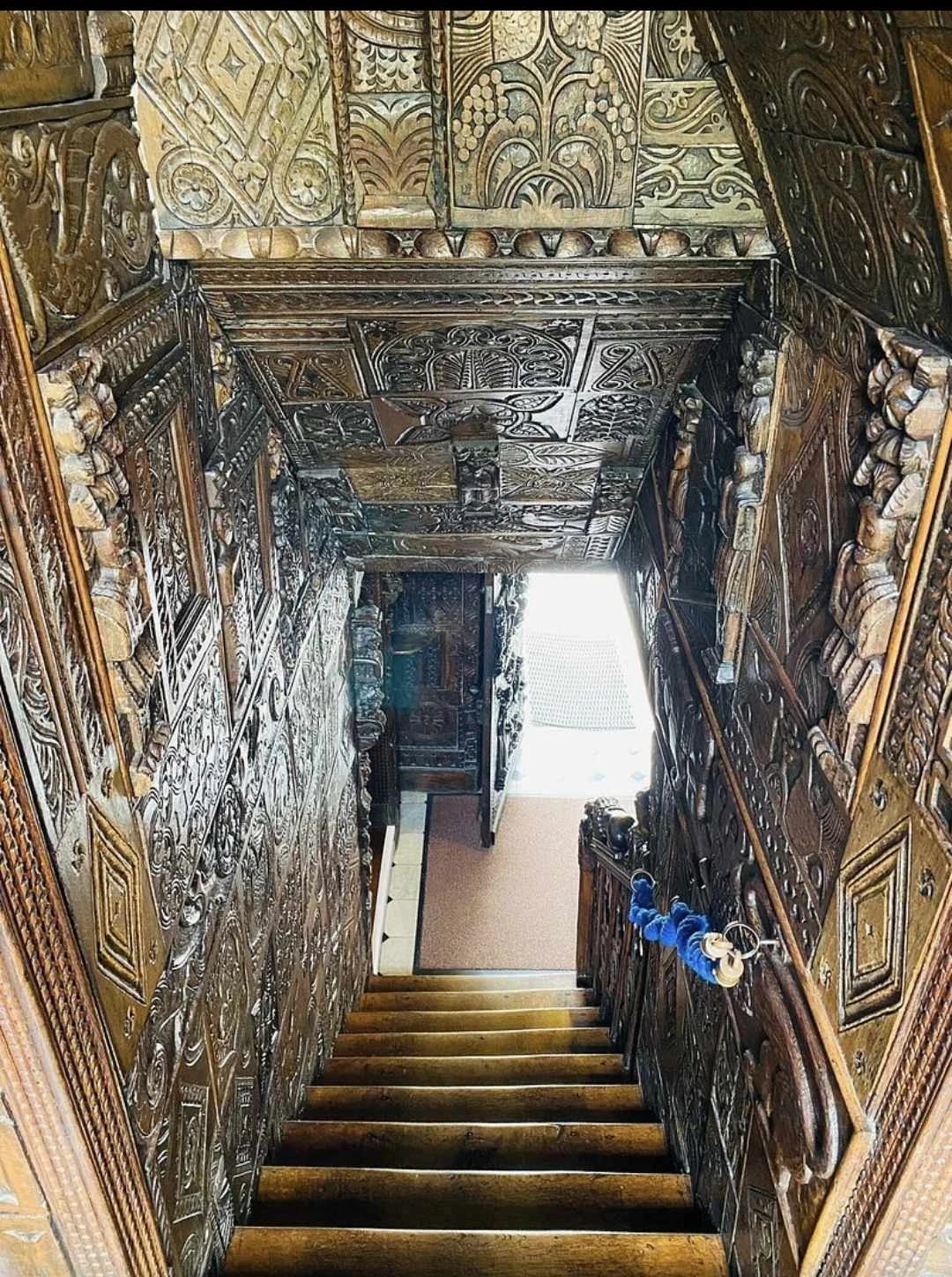

The stairs of Plas Newydd, Plas Newydd House Museum and Tearooms, All You Need to Know Before You Go (2024)

Accessed: November 2024

I went into their house only once as a child (Nanna knew the lady on the door and we got in for free, but only downstairs), and I distinctly remember the dark embossed almost leather-like wallpaper in the hall and stairs being delicately picked off by an American visitor as a ‘souvenir’.

The inside of that house was a dark entity, the polar opposite from its fairytale outside of space, blue sky, flowers, and a mini Stonehenge. Inside it was a different matter. Ten-year-old Tina couldn’t imagine why any ‘Lady’ would live in such … gloom.

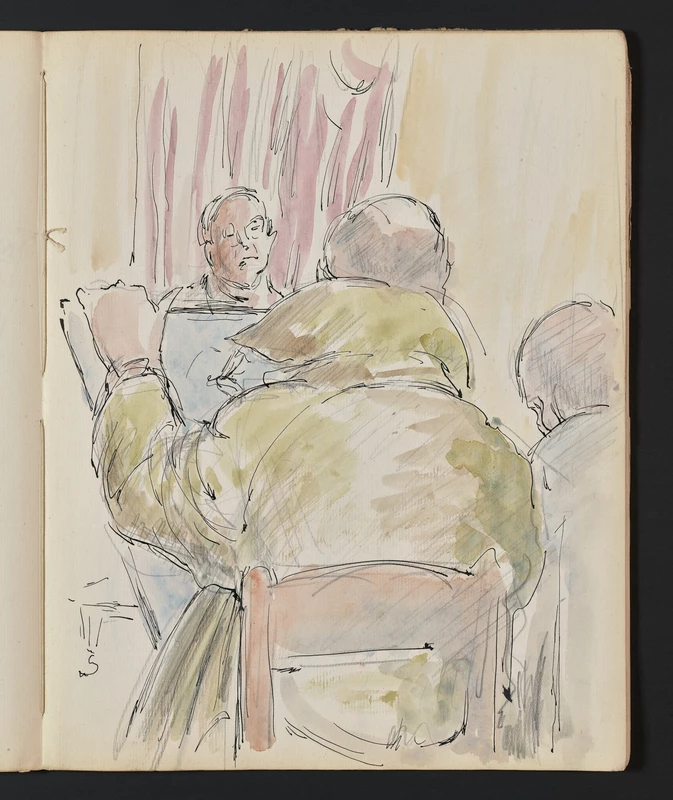

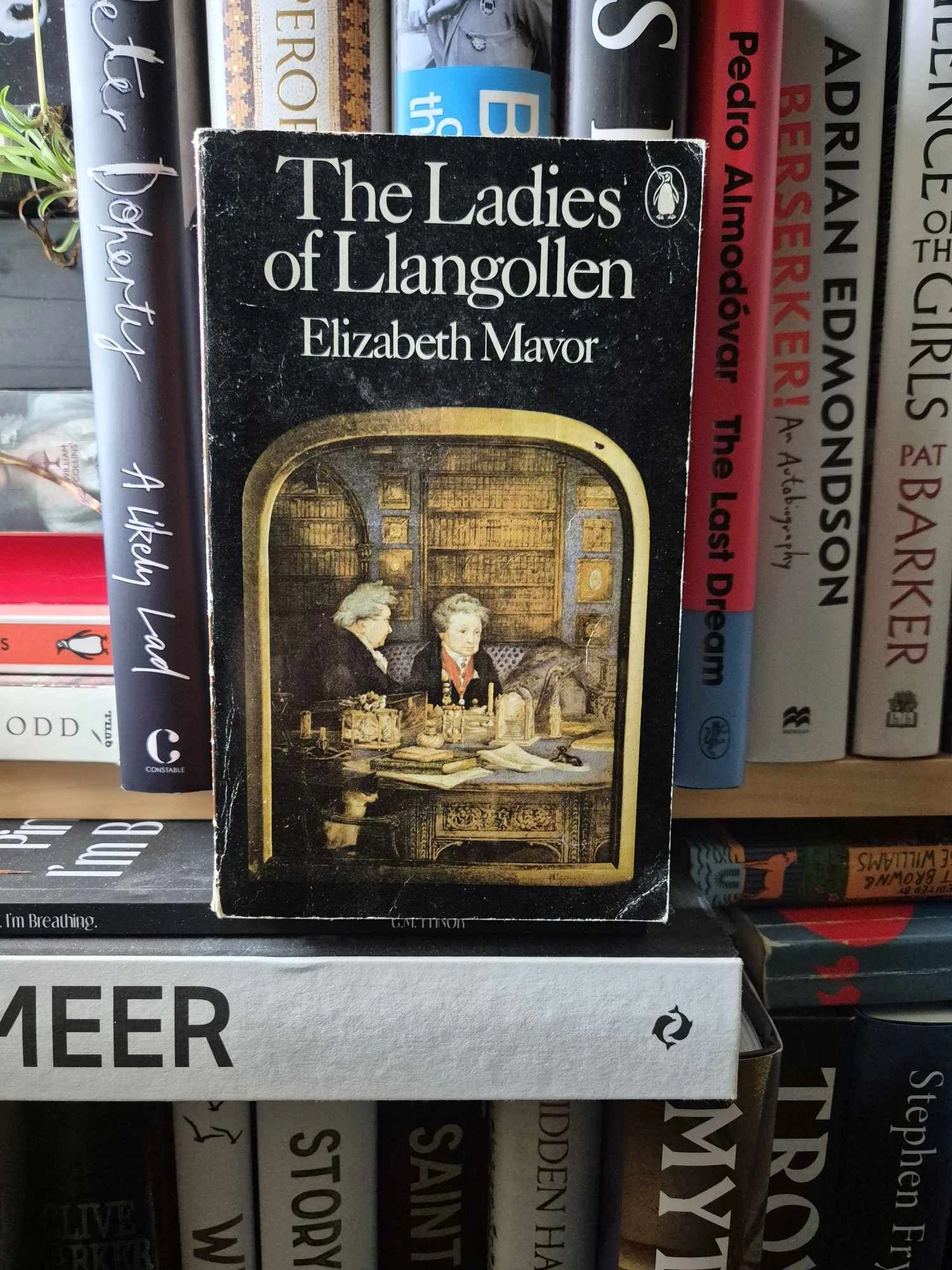

ROGERS, Tina, Photograph of Elizabeth Mavor's Book

The first time I saw Eleanor and Sarah was on the cover of Elizabeth Mavor’s book (I still have this book bought at a jumble sale in Chirk in 1982). A Penguin classic with an orange spine, the title ‘The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study in Romantic Friendship’ and underneath a colour painting of two people. On our left, a side view of a person (Sarah) looking at the person seated across from them, who in turn is looking to their left (Eleanor). Note, I don’t describe them as ‘women’ because in all truth, at age seventeen, I thought this picture was of two elderly men, some generic regency portrait, a case of ‘anything will do as long as it looks the part’ for the cover of this book.

Up until that point, I had imagined the Ladies to be full blown Disney Princesses, with white 17th century wigs, voluminous gowns, and fans. The dainty Cinderellas of Llangollen, these famous local women I knew absolutely nothing about. That idealist view was about to change as I began to read Mavor’s book about the lives of these two remarkable and complicated women.

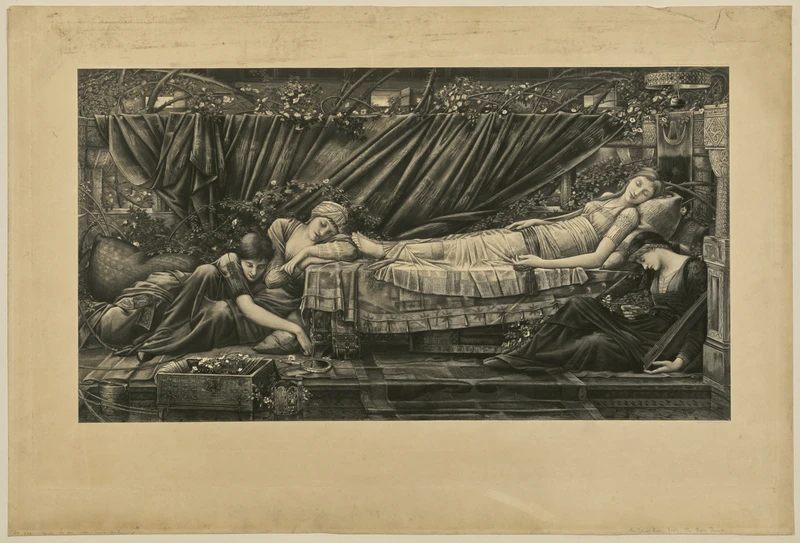

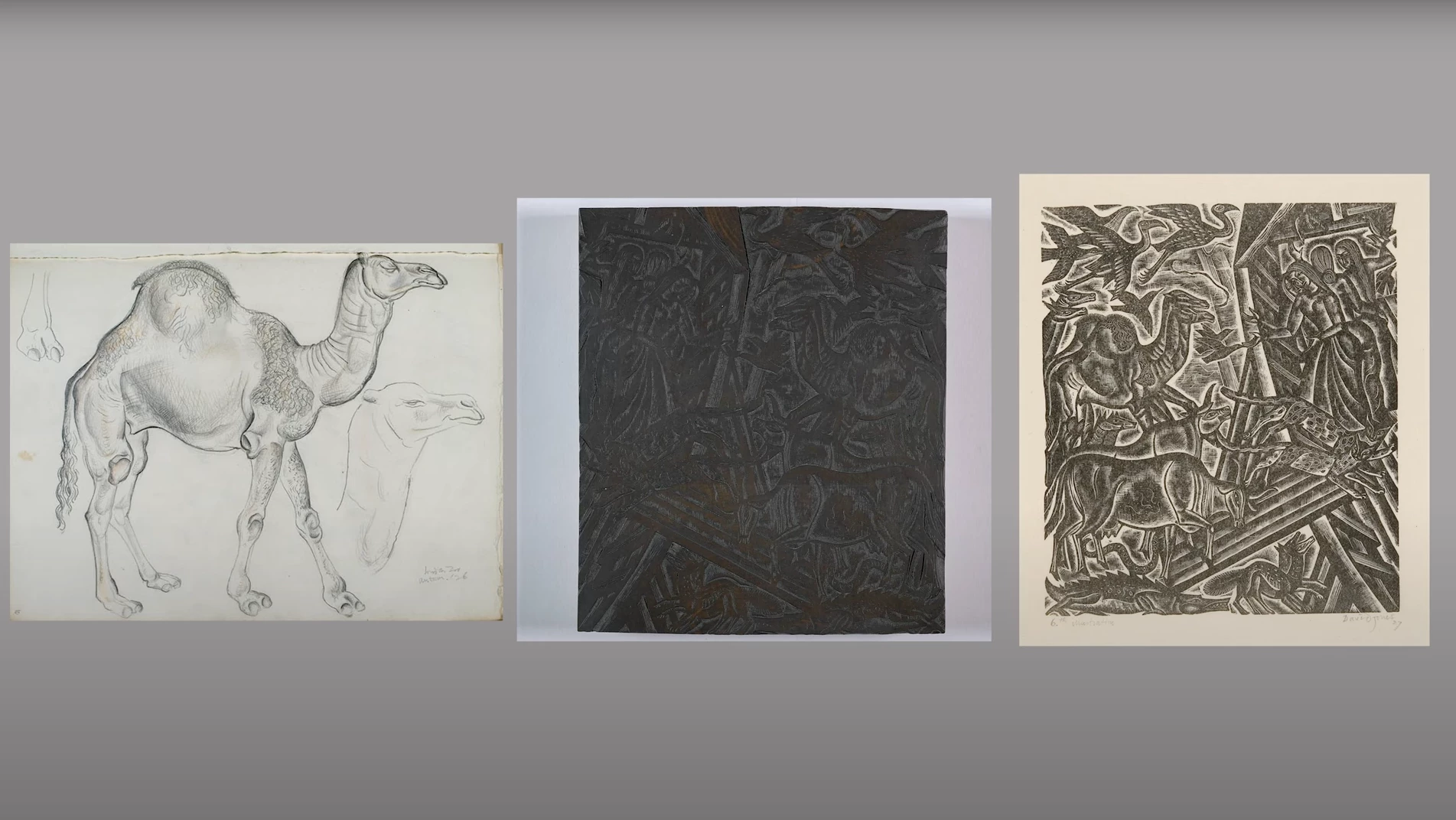

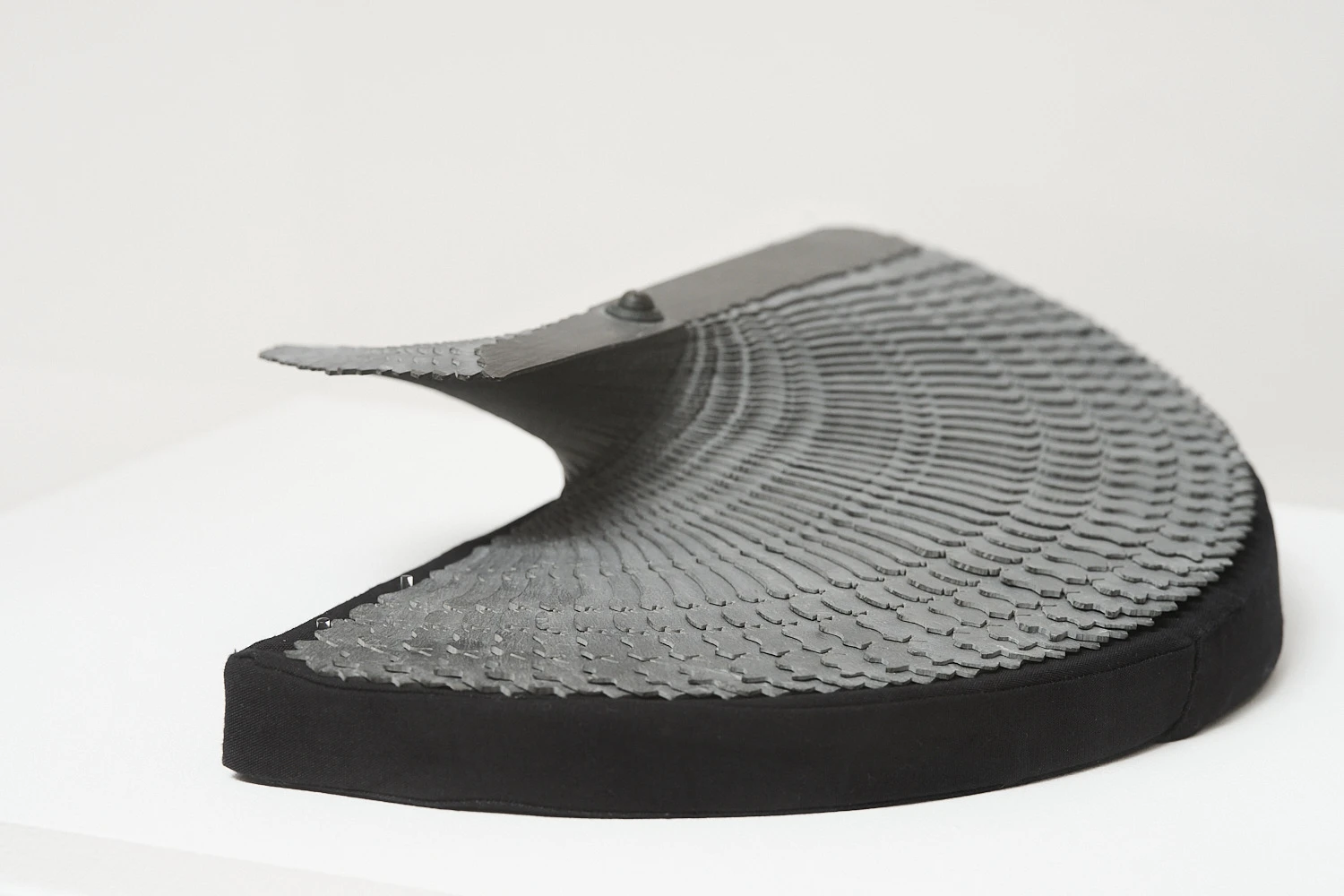

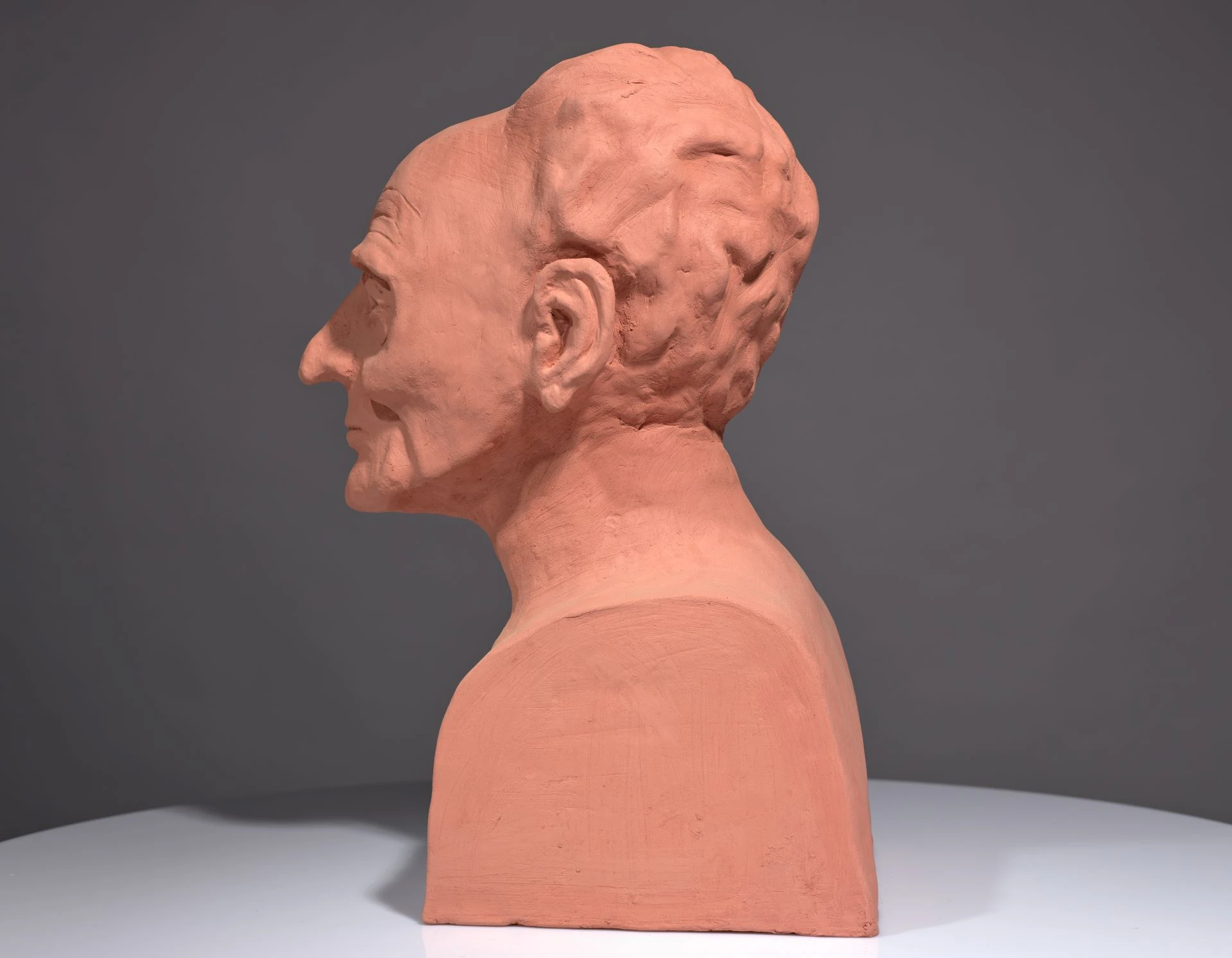

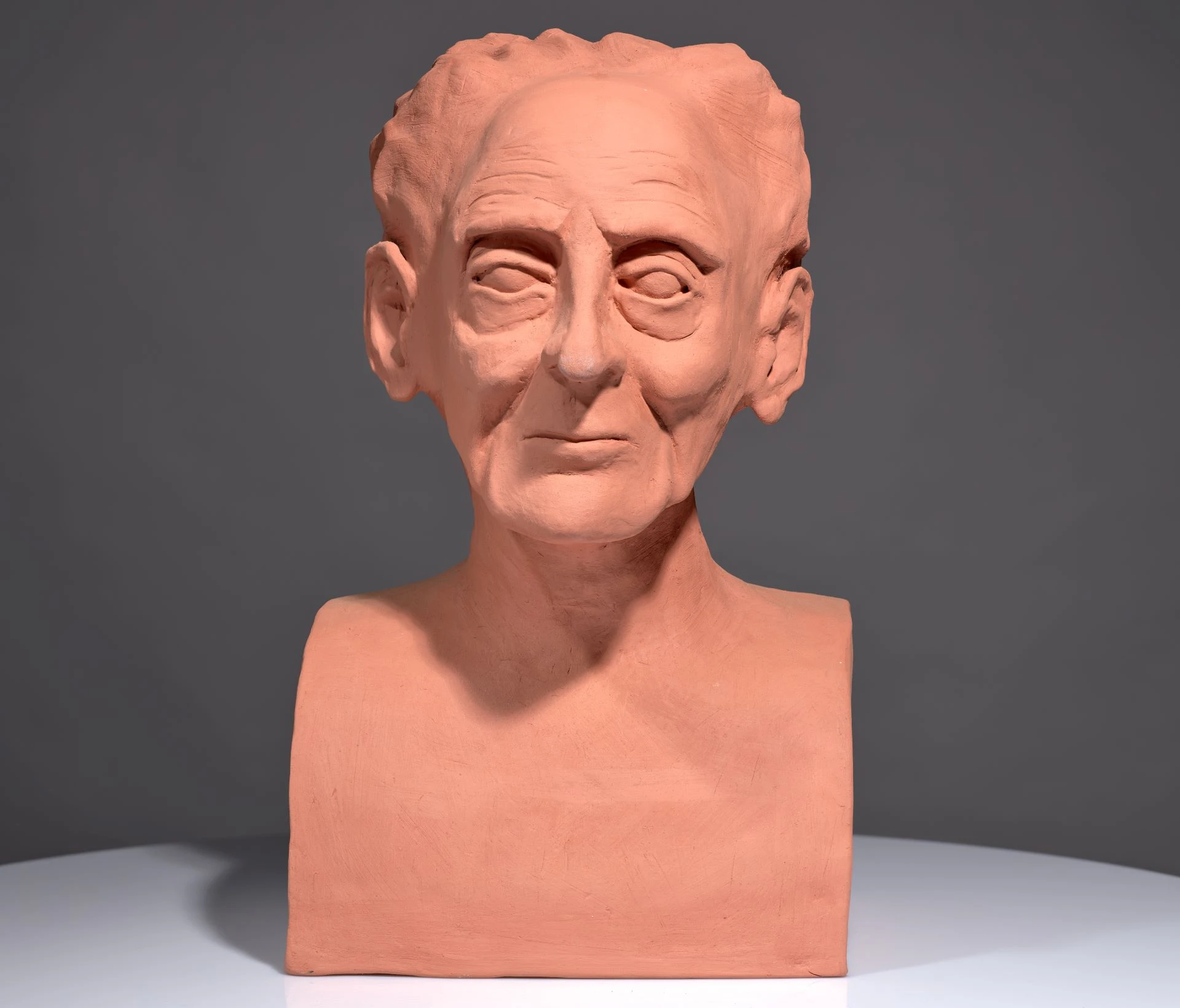

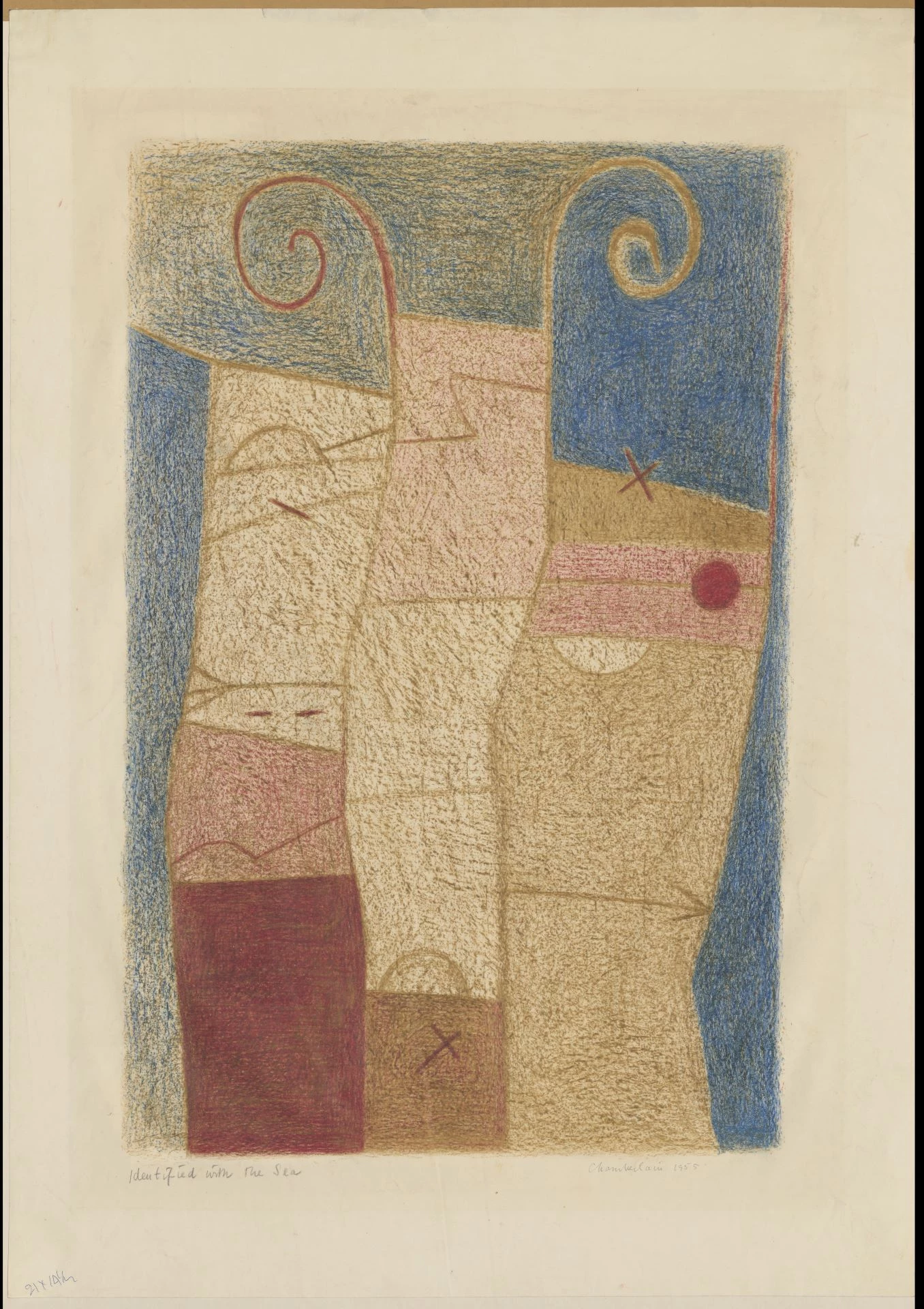

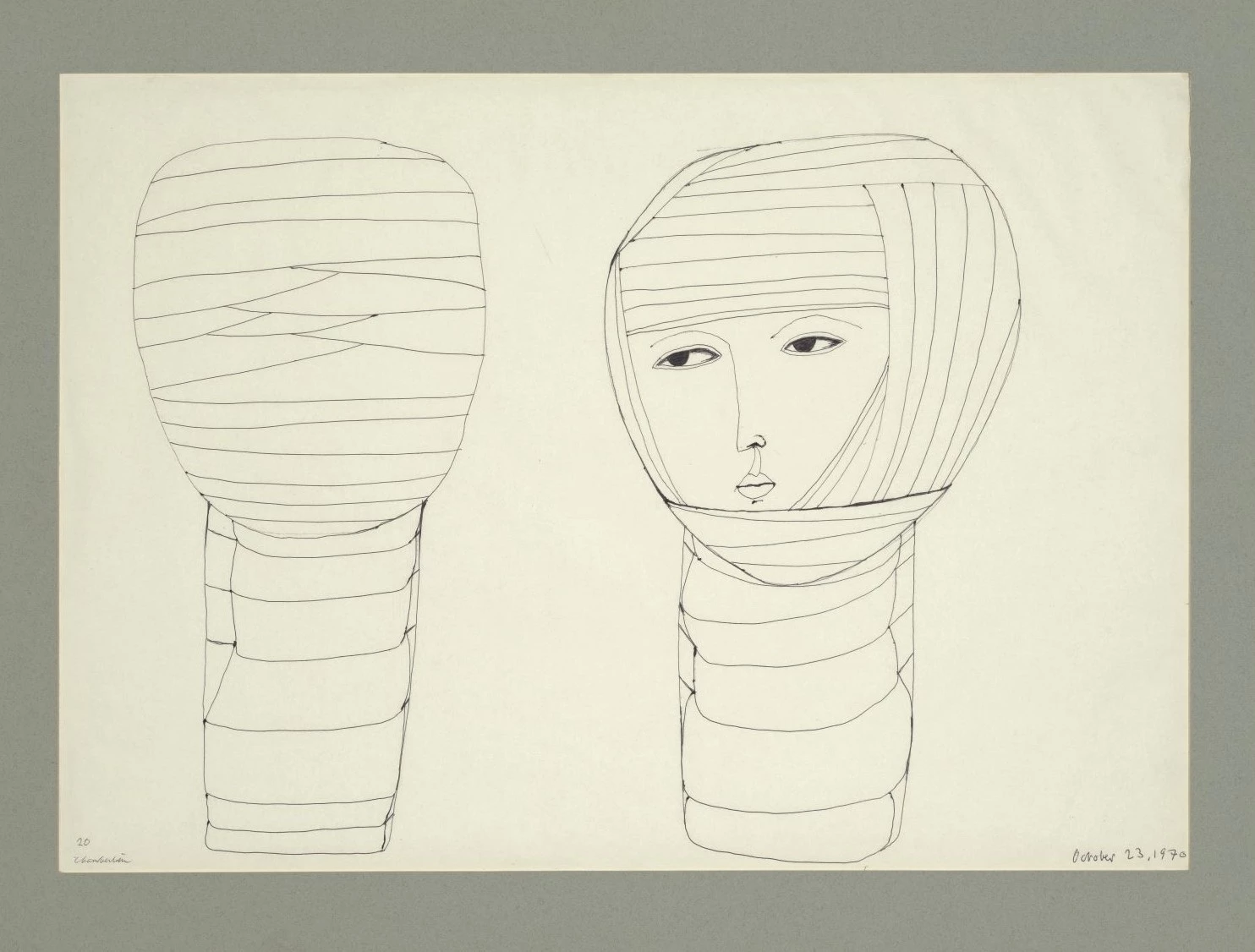

The Museum of Wales have a vast collection of art, one piece – Item number NMW A 29669 is a black ink on white paper original lithograph produced by Richard James Lane from a drawing copied many times in various forms (one being the artwork on the front of Elizabeth Mavor’s book) by Lady Leighton.1 She later admitted she drew Sarah and the now blind Eleanor ‘surreptitiously’ under the table while her mother distracted them without the Ladies’ knowledge as they disliked having their portraits drawn.

It seems the original portrait, which probably was drawn very quickly and was possibly of the Ladies’ heads and upper bodies with scant detail, is now lost to time, and this more ‘involved’ portrait was committed to paper sometime later presumably by Lady Leighton.

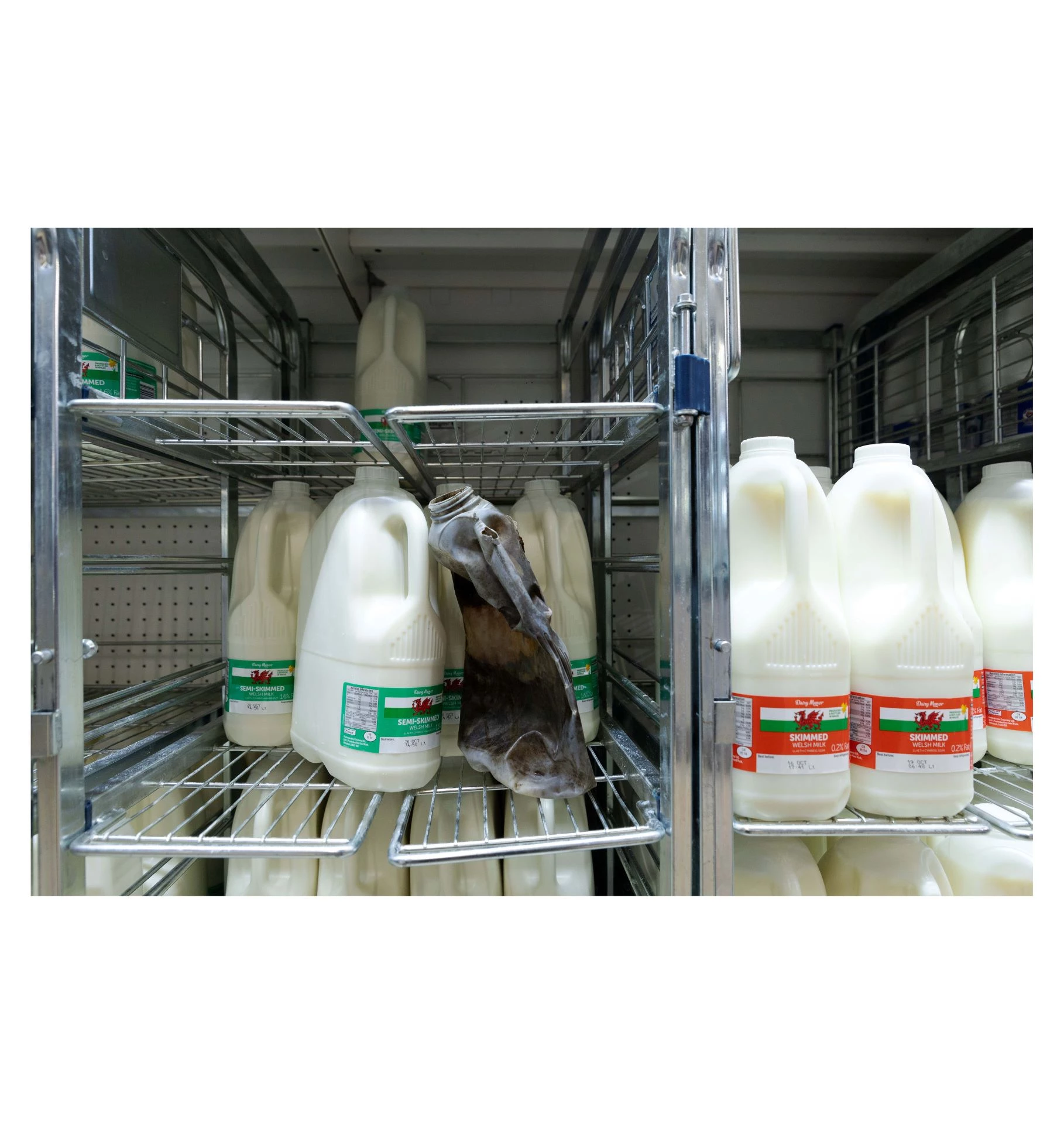

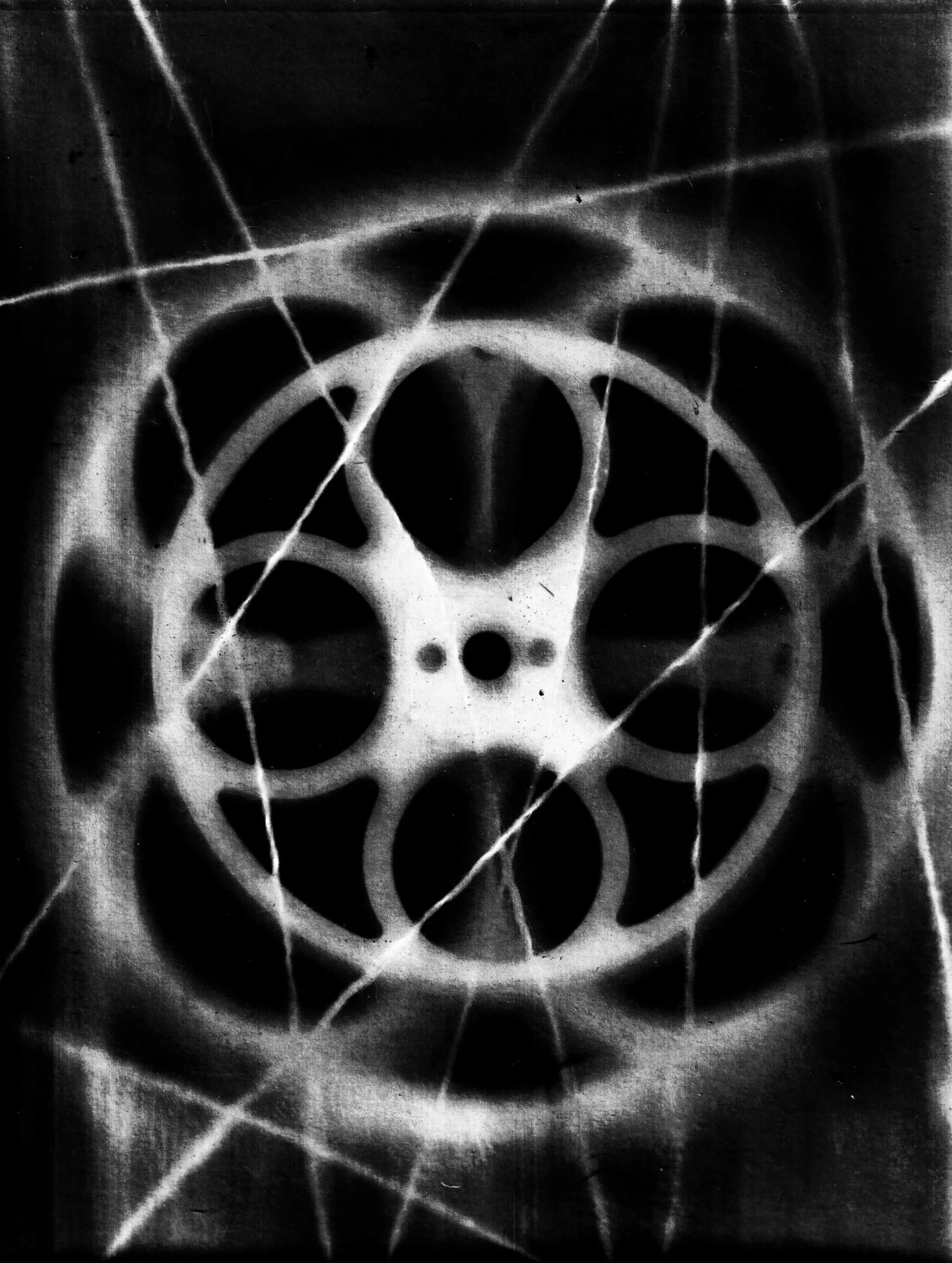

During their own lifetime, the Ladies were celebrated in surprisingly commercial ways, from tapestries to plates. This plate was produced by Glamorgan Pottery between 1815–25 (Eleanor died in 1829, Sarah in 1831), it went on to become one of that Pottery’s most famous and collectable pieces.2

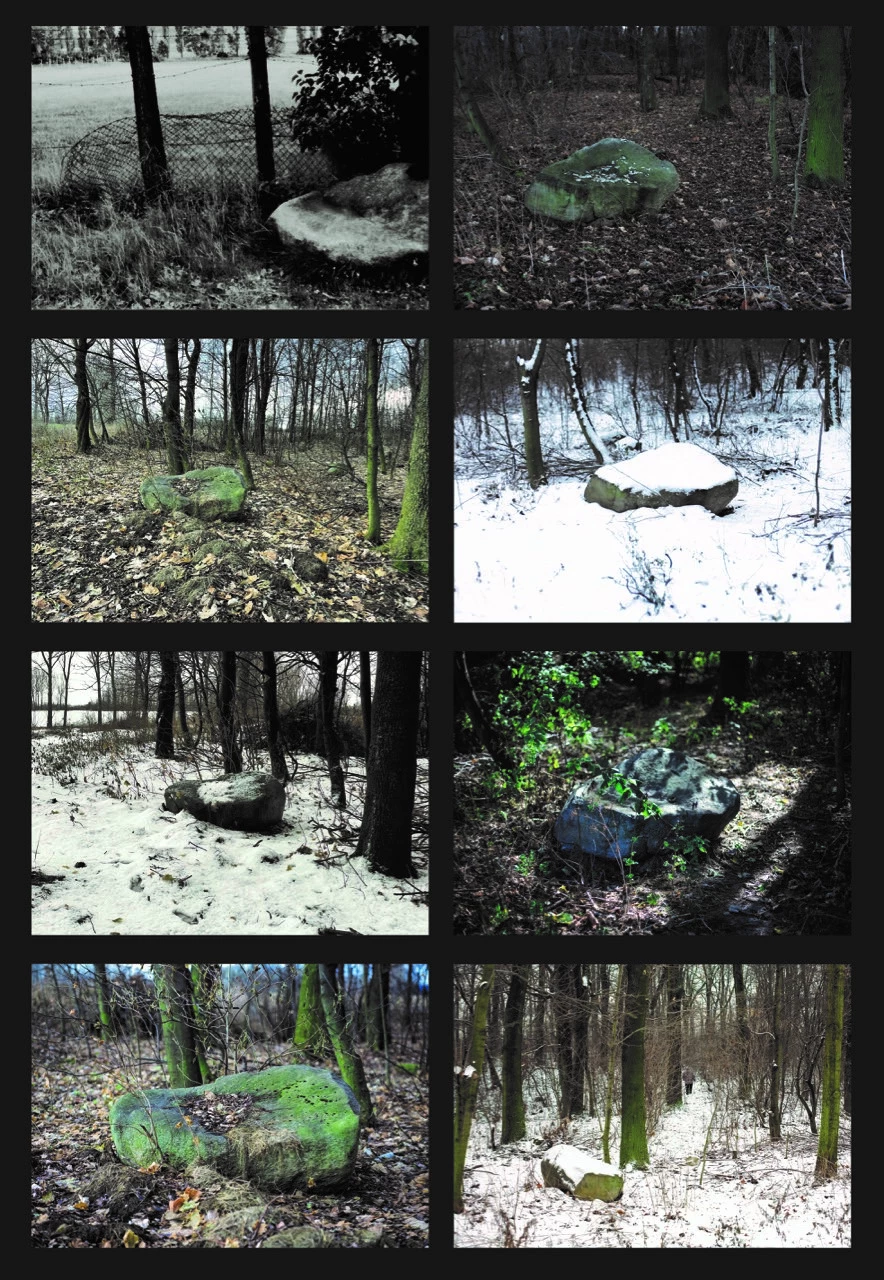

ROGERS, Tina (2017) The ‘stolen’ font from Valle Crucis, in the Ladies Garden. Plas Newydd.

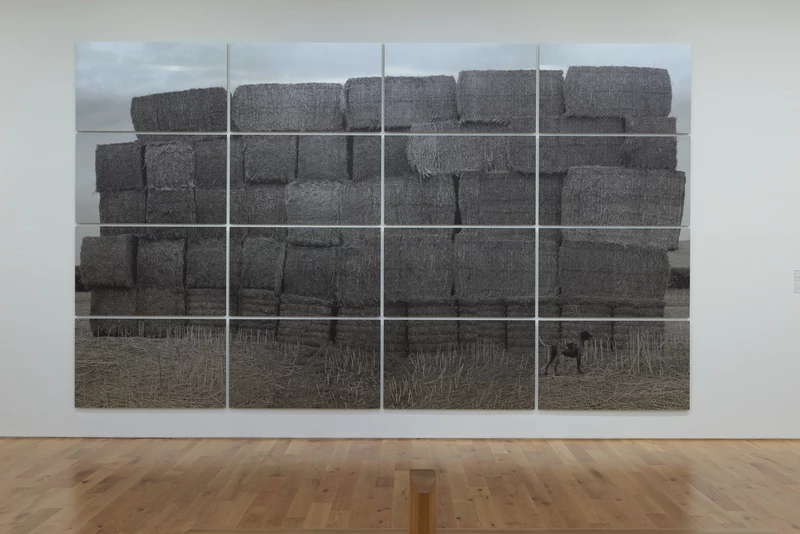

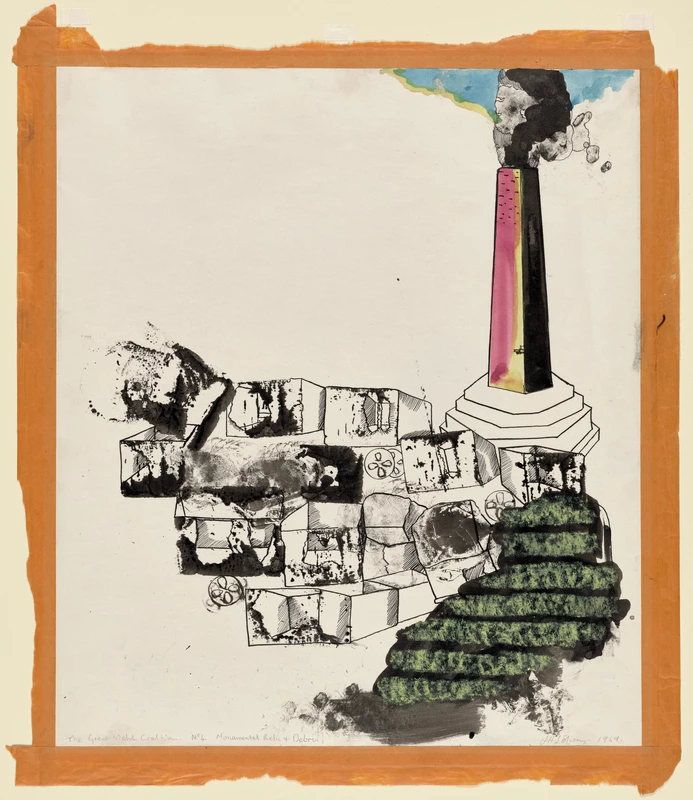

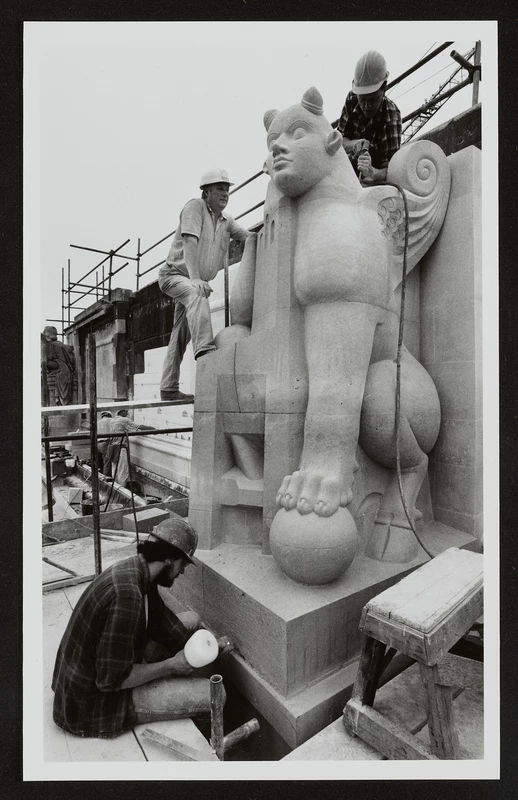

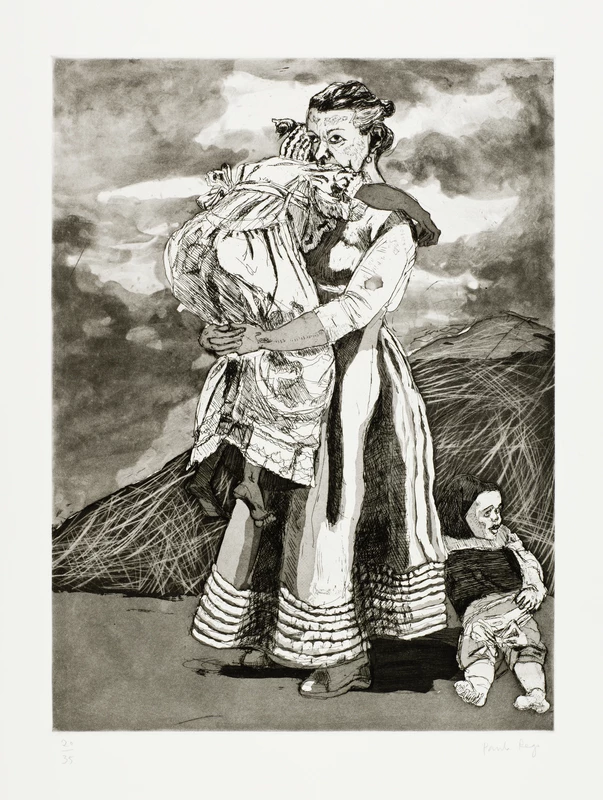

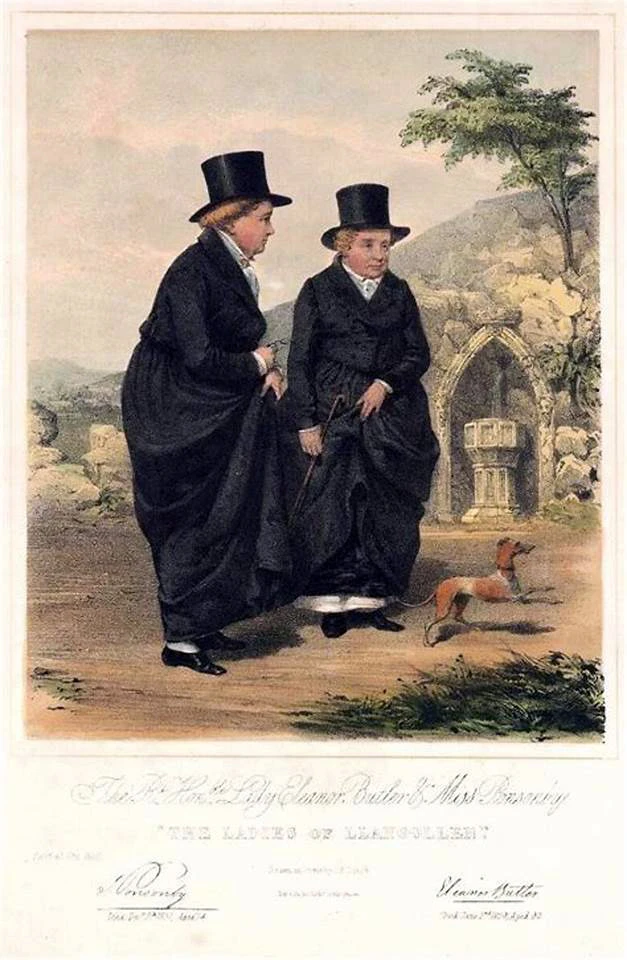

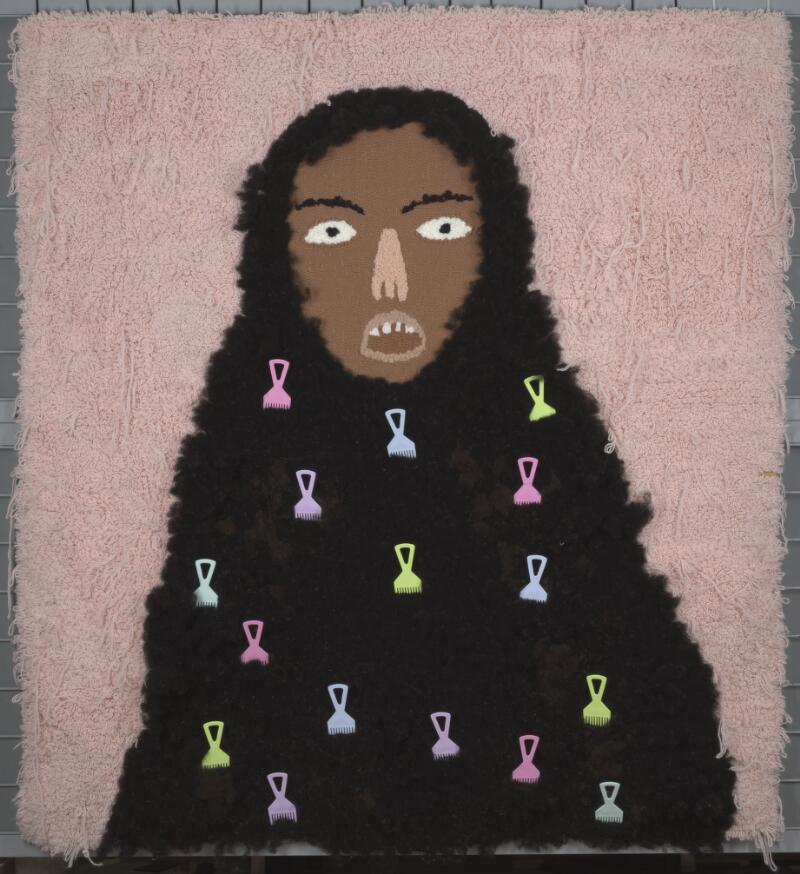

LYNCH, James Henry, Portrait of The Rt. Honble. Lady Eleanor Butler & Miss Ponsonby 'The Ladies of Llangollen'

For whatever reason, Mr Lane decided to take Leighton’s now embellished ‘sitting in a library’ portrait and create a lithograph, print it, and make it available for sale in 1830. That was not the only lithograph. James Henry Lynch also took the Leighton portrait and changed it so that the Ladies grew legs to stand and survey their garden next to the font, they ‘acquired’ from the ruins Valle Crucis Abbey (the Ladies were very keen to ‘re-use’ things they ‘found’), along with an unknown whippet-like dog.

Despite both Ladies keeping diaries, there is no mention of plates, nor did they write anything about their friend Lady Leighton secretly drawing them, or the mass production of those drawings for sale. Knowing the Ladies’ history and how they would write about the most trivial besmirchment, one can assume that they had no idea about the cottage industry built up around their celebrity for passing tourists to buy trinkets of them.

Perhaps the most famous piece of memorabilia of the two Ladies is this very lithograph, as the two other portraits of Sarah and Eleanor, are only purported to be them. The lithograph is still available to buy online today, and Plas Newydd itself sells prints of the Lynch portrait.

The Leighton-Lane Lithograph is important, as there are many written descriptions of the Ladies in later life, but here we have the only pictorial depiction of them that is ‘true’.

We know that Lady Leighton did a quick sketch of her friends, and it’s acceptable to assume that this sketch would concentrate largely on their faces and shapes and not so much on the detail of their surroundings. However, Lady Leighton was a close friend and visited them frequently, so one may also assume that this portrait is not only a good likeness of Sarah and Eleanor, but an accurate depiction of their surroundings even though drawn from memory.

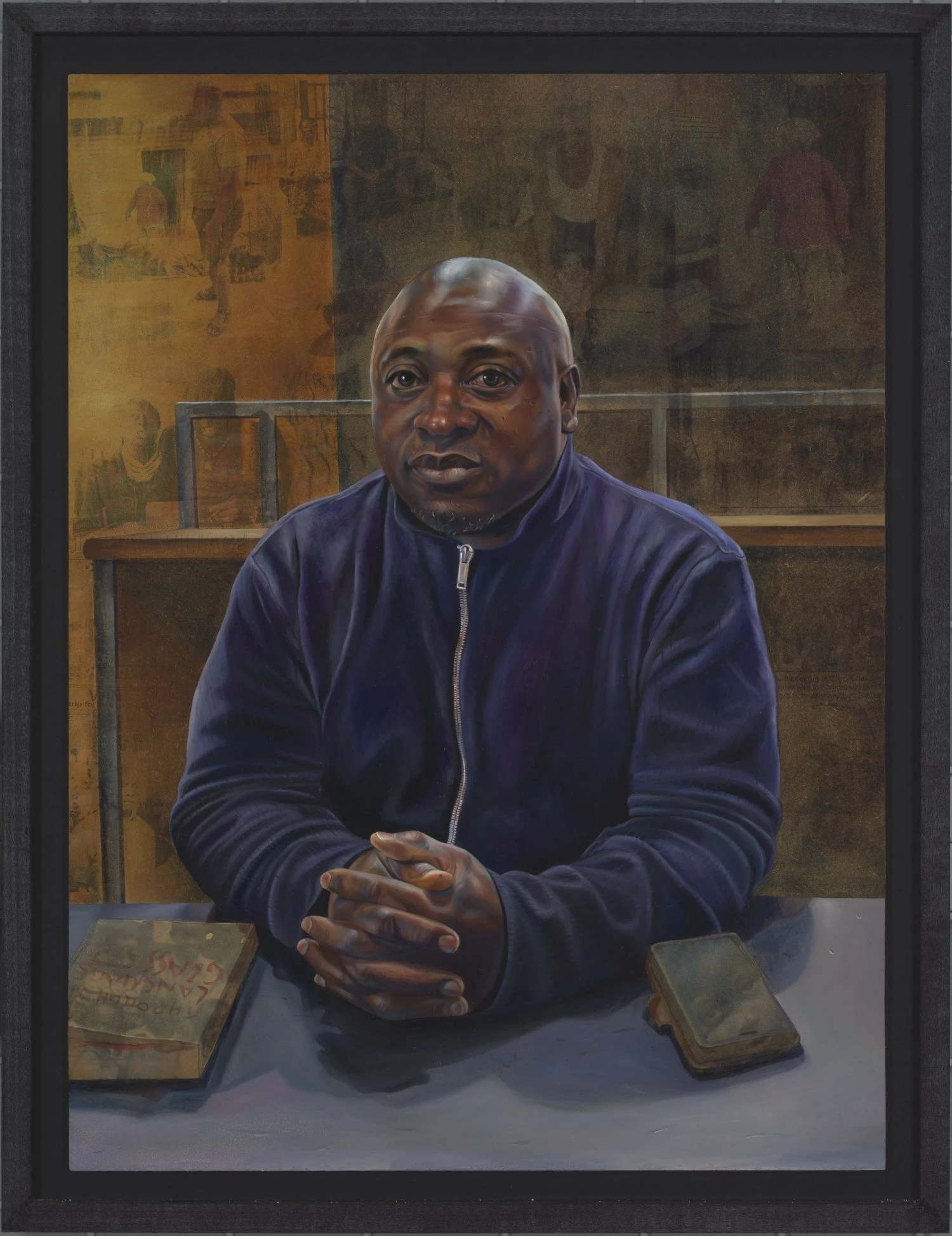

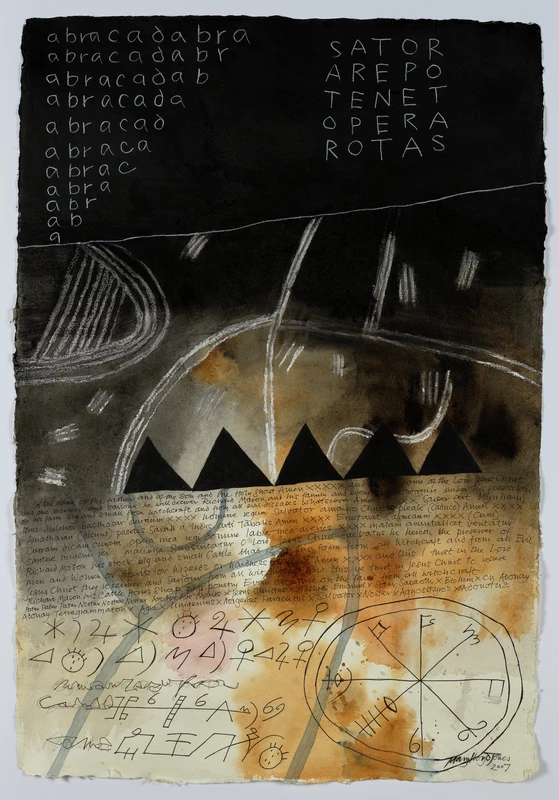

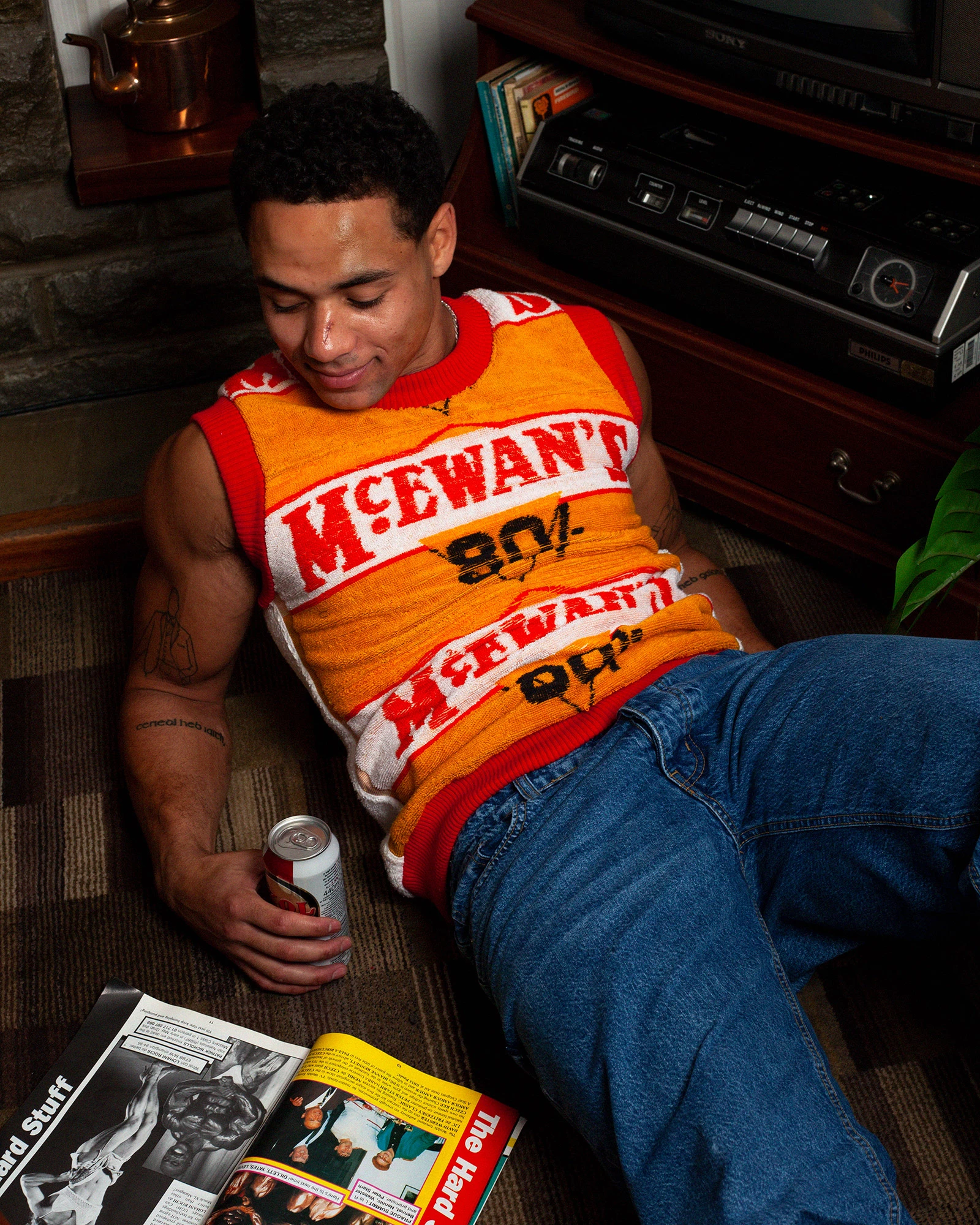

Let’s study this Lithograph on paper in black and white – ‘Portrait of the Ladies Of Llangollen’ and reflect on these most unusual women.

Their ‘her’-story if you will.

The drawing itself is very accomplished with amazing detail throughout. The Ladies sit in what looks to be a somewhat ‘gothic’ study or library, behind them are paintings and also shelves of hardback books in large ceiling-height bookcases and a Gothically spired-shaped alcove, this indicates that they are not only financially secure (the books, the comfort) but are educated, and from that, one may assume that these two Ladies come from the ‘upper’ classes.

They sit at a large and ornately carved wooden table (much like the rest of the house. The one request the Ladies asked visitors to bring as gifts was their old oak furniture, which they would chop up and re-use in the house. The four elaborately carved posts at the front porch are 4 re-used bed posts). In the coloured version of the portrait, the walls and table covering are cerulean blue. This table has an array of unknown and exciting of things on it.

The order of St Louis as worn by Eleanor Butler, Coins la Galerie Numismatique

Accessed: November 2024

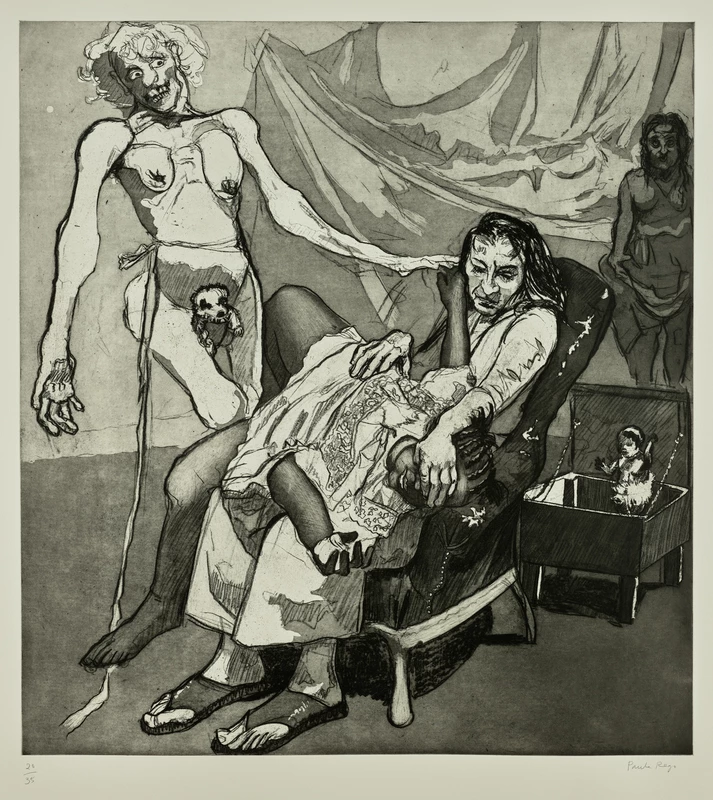

A writing desk (the Ladies were both great writers), candles and an oil lamp. Piles of paper and books are strewn across the table, along with an egg timer (perhaps Lady Leighton added this as a reminder that their ‘time’ was running out), and a few baroque perfume bottles. Near to Eleanor, who has several elaborate, large and royal looking medals on her chest, one being the Order Of Saint Louis, given to her by a member of the Bourbon Family, is a glass box, it looks to have ten sides and, in that box, appears to be a pine cone and an object that might be an ornament of fruit, as it has a stalk, and on top of the box lies some dried flowers. To the right of Eleanor is perhaps the most interesting item on the table, another box made of glass, highly ornate and arched, that contains what looks to be a tomb with a dead person lying prone on top, like a medieval King. Next to that is a miniature spire and a small dog ornament.

When Sarah died, her relatives held a seven-day sale of goods at Plas Newydd, there was nothing left, everything was sold from Telescopes to Tiger’s feet. A quest to find out about these items and where they ended up has drawn a complete blank. A lady who presently works as a guide in Plas Newydd told me 6 years ago two visitors who work as guides at Powis Castle3 had seen the glass case with a tomb inside as part of the castle’s collection. Sadly, all emails are unanswered, and I’ve been unable to talk to anyone from the National Trust or Powis Castle to confirm this. All the Ladies’ worldly goods were scattered across Britain and possibly further afield.

This ‘smorgasbord’ of items can give us a look into the lives of the Ladies, but the central focus of this portrait are the Ladies themselves, these two tiny women with black riding coats, short white powdered manly hair, and faces similar to Kewpie dolls, were described by the actor Charles Matthews in 1820 when he was performing in Oswestry on writing to his wife -

And in 1825 John Lockhart who visited the Ladies with Sir Walter Scott wrote -

Not a very polite description of them because they did not dress or ‘behave’ as women should.

It seems that people who wrote about them, and perhaps the people who met them thought them both as not androgynous, but as ‘manly’, and rather odd and this, I believe, is where their fame originated, and continued.

Two women living together in a ‘romantic friendship’5 at a time when the majority of people had no idea that it was possible for women to be sexually involved, and also reject the idea of femininity, marriage and motherhood, and live for themselves with no man involved whether it be a husband, or family member.

In order to get an idea of who these women were and why they not only ended up in north Wales, but became famous in their own lifetimes with visits from the most incredible array of contemporary well-known people from Wordsworth, Byron and Shelley to the nation’s (then) hero, The Duke of Wellington, we must look at their story, and it really is something worthy of a BBC1, Sunday night historical series.

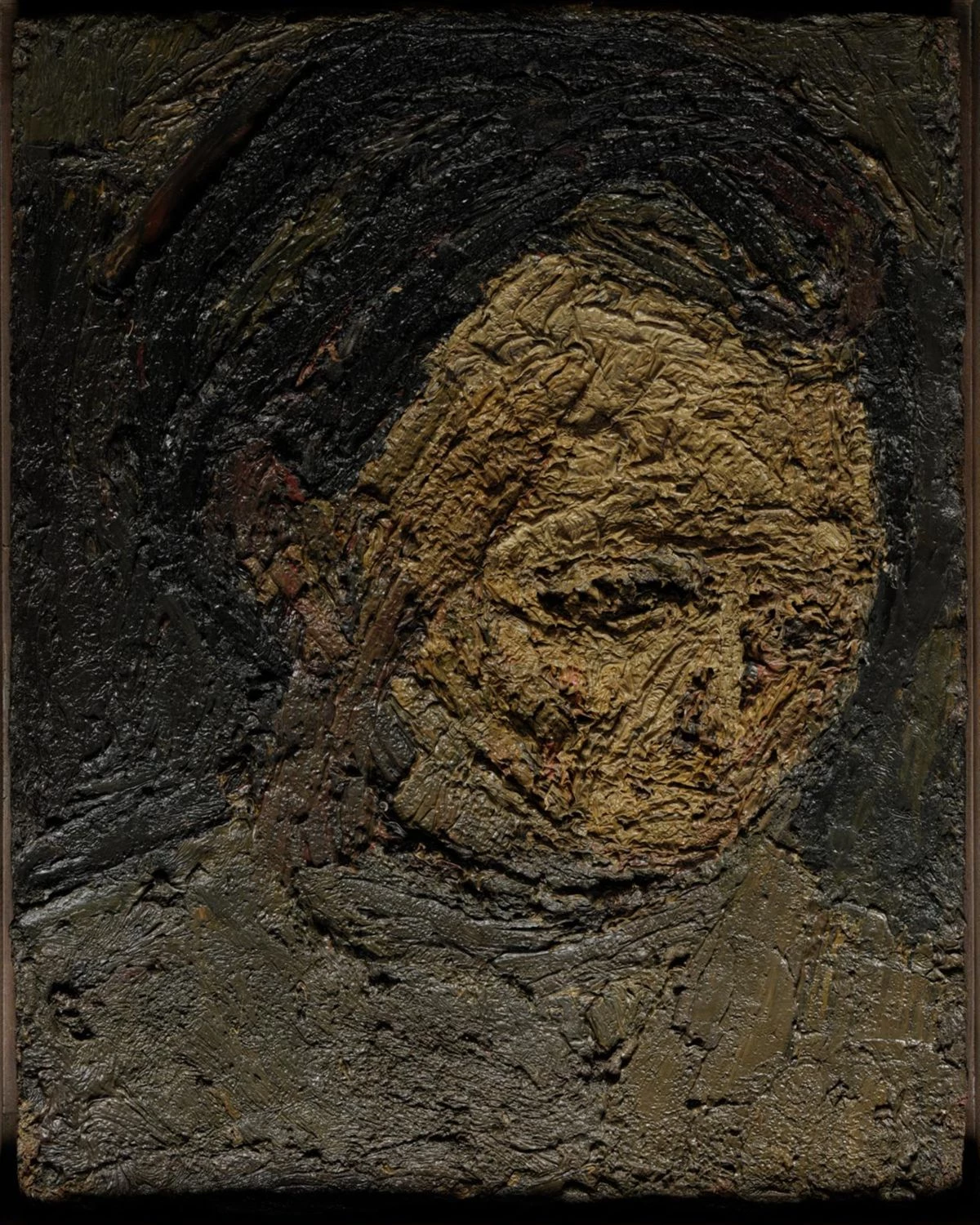

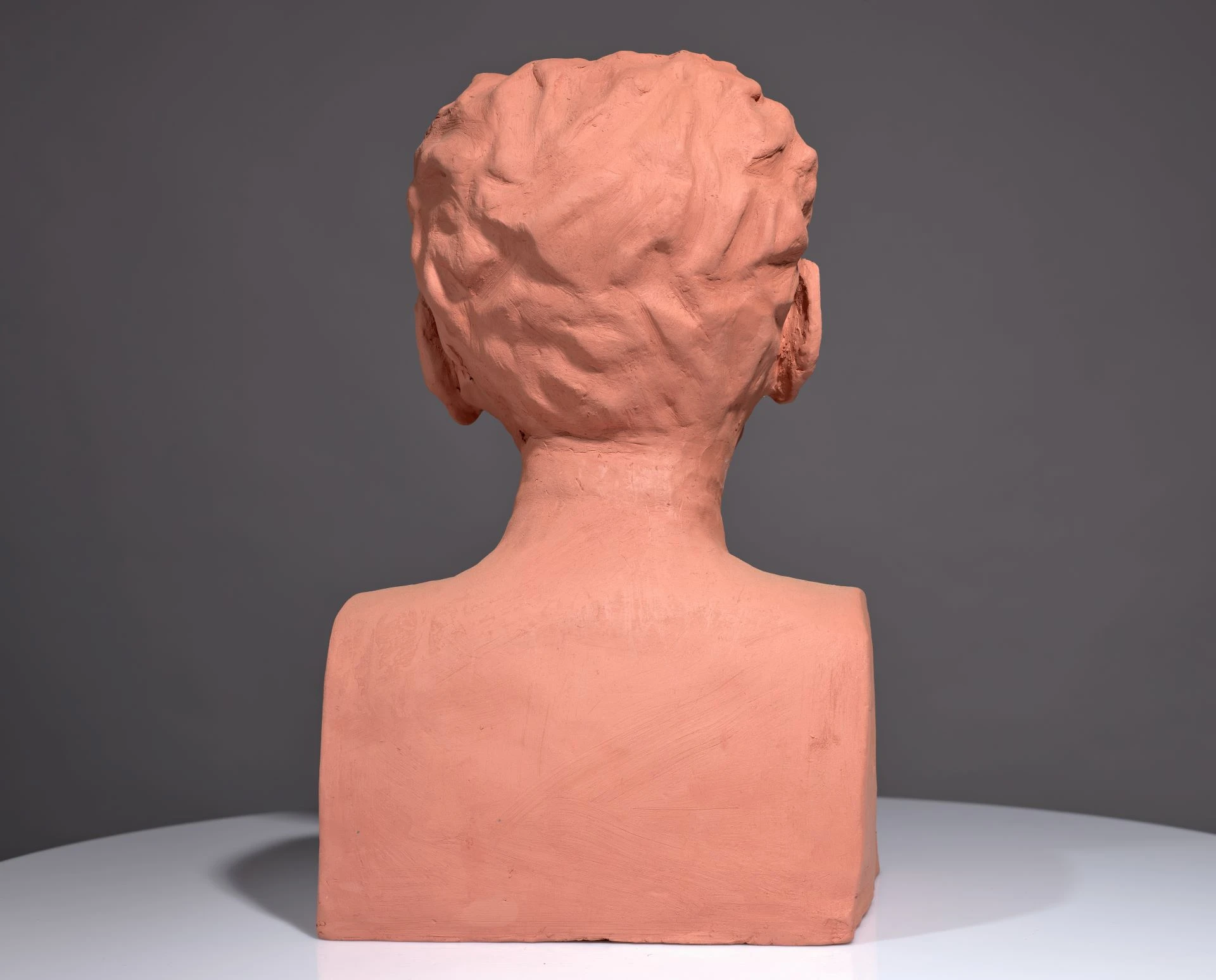

This portrait is purported to be Eleanor Butler - but there is no solid evidence to prove it is her Birth of Eleanor Charlotte Butler, Recluse of Llangollen | seamus dubhghaill

Accessed: November 2024

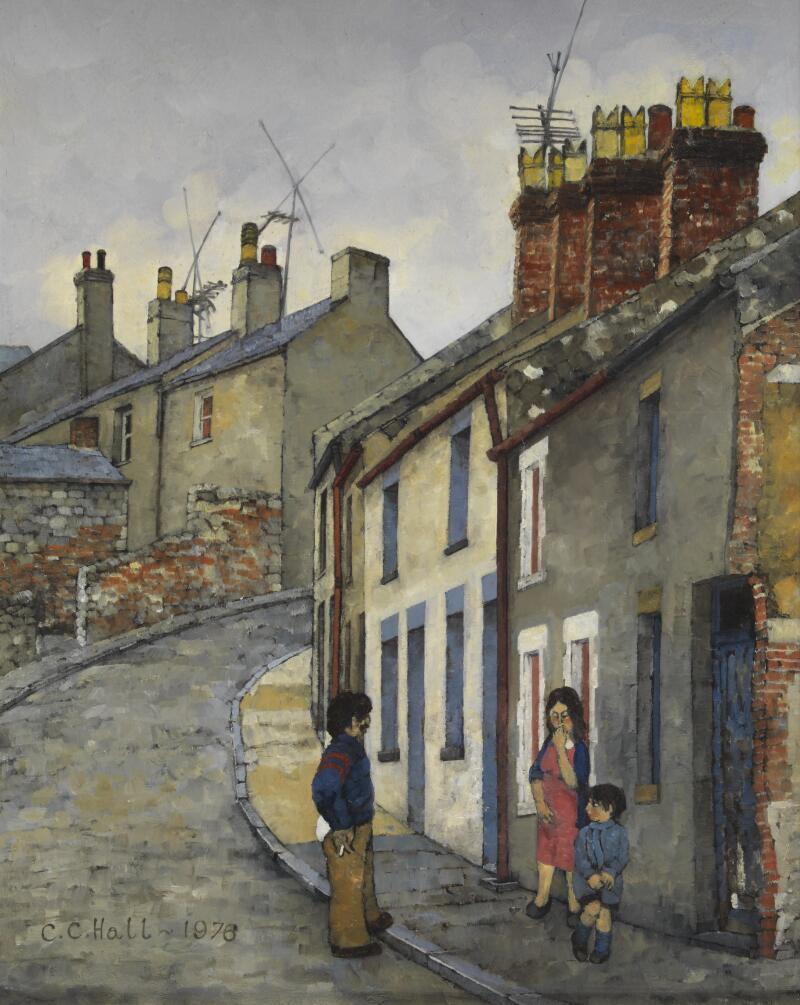

Eleanor Charlotte Butler was born in Ireland in May 1739 and died in Llangollen in June 1829. She was the daughter of Walter Butler, the 16th Earl of Ormonde and she grew up in the ramshackle Kilkenny Castle, Ireland. The family remained staunchly Catholic which meant they had the pedigree, but not the money or power of a Protestant Earl because of the penal code . As a Lady, Eleanor would be expected to be a brood mare for some local suitably aristocratic man, and in preparation she was packed off aged around 14 to a convent in Cambrai, France where the Butlers had family ties. There are no descriptions of Eleanor during this period, save her aunty deciding not to leave Nelly a ‘dear little ring’, as her fingers were now ‘too fat’. It seems Nelly (Eleanor) was happy at the convent, as for the rest of her life, she would swear, sing and rejoice in French. There is a gap in her story from 14, until we know she was back in Ireland for her brother’s wedding in 1768 at age 29.

Eleanor was educated but unmarried, a spinster, and therefore a burden on her family.

It was around this time that Eleanor met Sarah for the first time.

Elizabeth Mavor suggests this might be a portrait of a young Sarah Ponsonby, again there is no real proof that it is her.

Mavor, Elizabeth, The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship, Moonrise Press 2011

Sarah Ponsonby was also born in Ireland, about 20 miles away from Kilkenny Castle at Woodstock to new Protestant money in 1755. She was a result of her father’s second marriage. By the time she was thirteen Sarah was an orphan and destitute. She was sent to live with her father’s cousin, Sir William Fownes and his wife, Lady Betty, and soon after was sent to boarding school in Kilkenny. Despite the families being of opposing religions, it seems the Fownes family reached out to the Butlers, knowing they lived so close, to ‘keep an eye’ on Sarah, and this led to the thirteen-year-old Sarah, meeting twenty-nine-year-old Eleanor.

Eleanor had two older sisters, both married, and now her brother John had abandoned the Catholic faith to become a Protestant, and this led to him making a very advantageous marriage to an heiress. All that was left for him to accomplish was sort out his ‘difficult’ sister Eleanor, who was a problem for the Butler family; a spinster with no desire to marry, being ‘too satirical and too masculine a style to attract men’.7

There is no record of how or when Sarah and Eleanor met, or indeed what form their friendship took. Some texts suggest that because Eleanor was in a Convent in France, she must have taught Sarah French, the truth is, we just don’t know. However, there is one thing I find not only interesting, but quite surprising and also rather worrying, and that is the age difference between them.

None of the modern texts, YouTube videos or podcasts I have looked at, have raised an eyebrow or questioned this. All, without exception, mention the age difference and ‘friendship’ and do not question it in any way.

Today, in 2025, if a thirteen-year-old girl was spending all of her time with a twenty-nine-year-old woman, I am sure that questions would be asked, and perhaps their relationship would be investigated to ensure ‘grooming’8 was not taking place.

Art and History are always reflected on and written about, compared with how we live now. Looking at Eleanor and Sarah’s relationship in 2024, after ‘#Metoo’ and many highly publicised cases of abuse, we’re now far more aware of sexual abuse, grooming, coercion, etc., and the fact that women are equally capable of committing these deeds as men.

In 1768 these things didn’t exist - that is to say they DID exist, but there was no name for them. A man could beat his wife as long as the stick was not thicker than his thumb, you could legally get married at 12, and even though evidence points towards Queen Anne having an affair with Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough in 1711, it appears that there was no such thing as lesbianism in the 1700s.

Sarah and Eleanor’s relationship could have been totally innocent, or something far more insidious, we will never know.

Sarah left school at eighteen, and moved back in with Lady Betty and her husband Sir William, while Eleanor continues to lives with her family at the castle. During those ‘missing’ years there is no real mention of either of our Ladies, but later, we find out from their friend Mrs Goddard, that Sally and Nelly (Sarah and Eleanor) never lose touch, in fact it appears their relationship intensifies particularly through letter writing.

The five years of calm are turned upside down when Sir William decides it’s time to replace Lady Betty with someone much younger and fertile. There was no son to pass the title to, and William’s eye soon settled on the now 23-year-old Sarah, his ward.

From letters kept by Sarah’s niece it appears Sir William had made it clear to Sarah that he’d like to not only marry her, but impregnate her, as Lady Betty was too old to give him a male heir and he thought he was still rather attractive. Again, we’ll never know what really happened, but the fact that Sarah wrote to Sir William while living in the same house as him, demanding that he only contact her by letter (she didn’t want to be anywhere near him physically), and tell her if she should leave the house. Was Sir William sexually harassing or abusing Sarah?

Writing to her friend Mrs Goddard -

What part did Lady Betty play in this? Words have different meanings now compared with then, so one can assume that ‘obliging’ simply means ‘be a bit nicer to your uncle’ - wouldn’t Lady Betty see Sarah’s discomfort? Or was she turning a blind eye to his behaviour because in 1778, women ‘belonged’ to men, especially if you were his ward, his daughter or were married to him.

Eleanor was also having a hard time, now aged 39 and ‘too manly’ and too old to attract a husband, her father and brother had had enough of her, so her mother demanded she enter a convent in France. It seems that Mrs Goddard, a mutual friend of the Ladies, received a letter on a Friday night in April 1778 from Lady Betty -

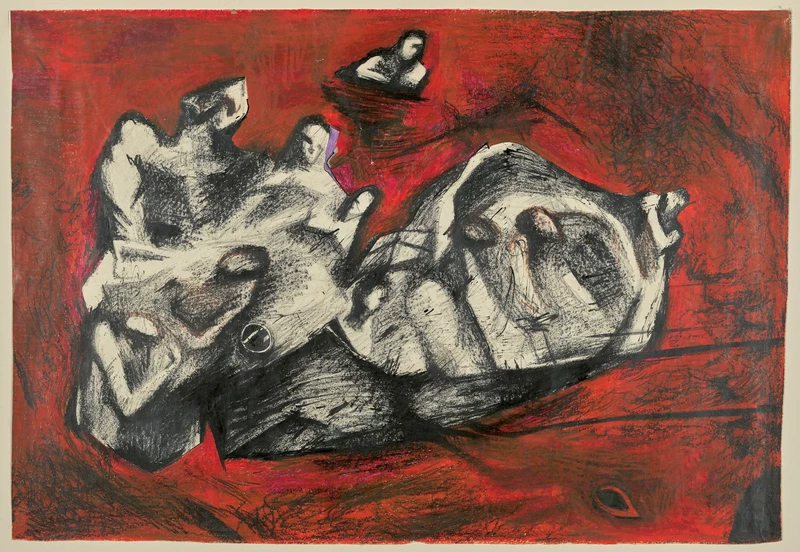

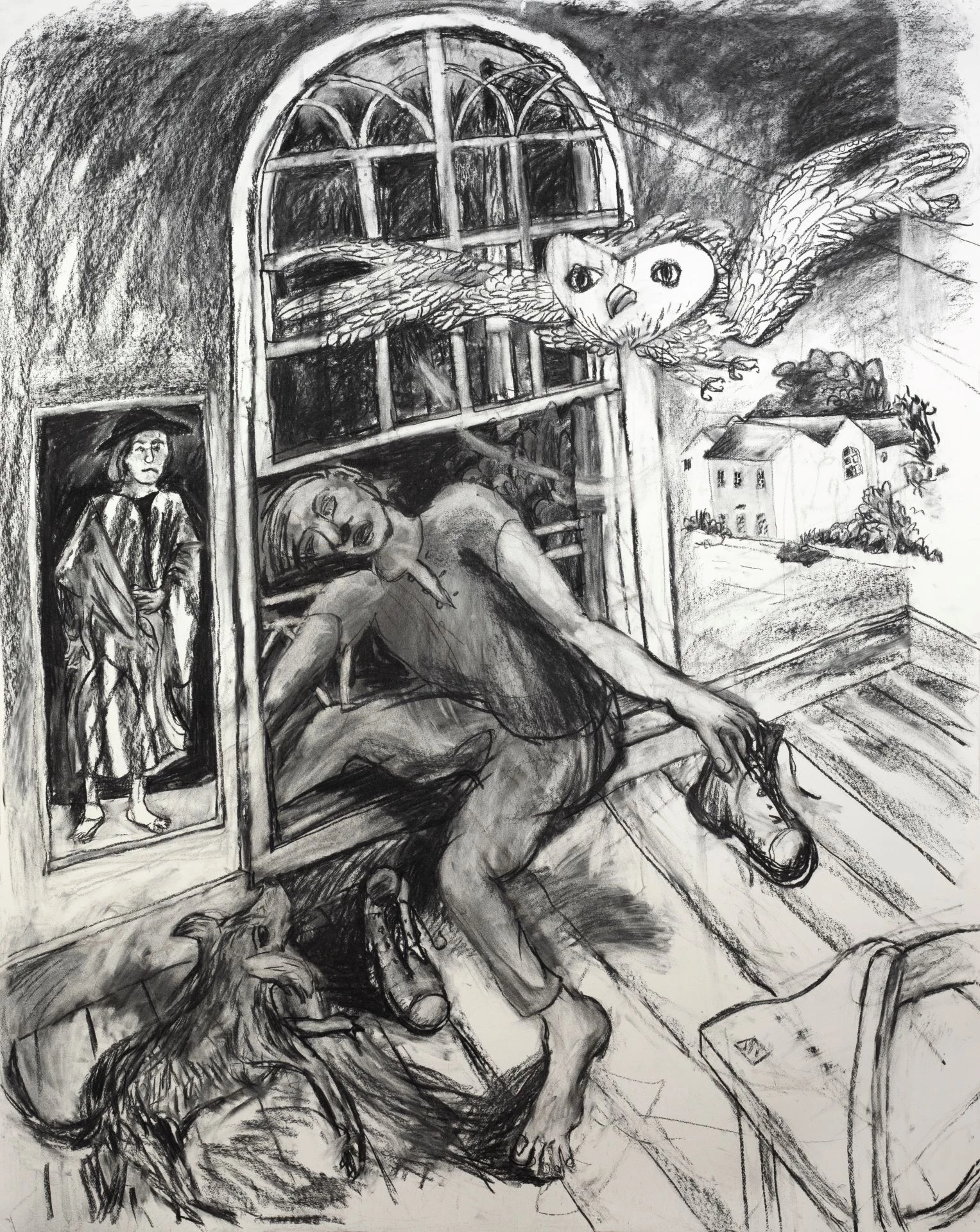

Eleanor and Sarah had eloped.11

Dressed in men’s clothing, with Sarah holding her dog Frisk, and a loaded pistol about her person, they headed to Waterford to catch the boat to England and freedom. They missed the boat, and the next morning Lady Betty and Mrs Goddard found them hiding in a barn, and on taking them back to Sarah’s home, they were intercepted by the Butler family, who literally dragged a hysterical Eleanor away. Sarah then admitted that they had been planning to leave for some time and live together.

Lady Betty’s daughter (who ended up being a life-long friend to the Ladies) Mrs Sarah Tighe, along with Lady Betty were delighted there was no impropriety involved as it seemed that there were ‘No gentlemen concerned’.

The fact that Sarah and Eleanor may have been lovers was incomprehensible to them.

Sarah became ill with a chill, while Eleanor was no longer wanted at the family castle and had to stay with her brother-in-law until she left for the convent in France. Correspondence between various members of the families and friends indicate that Sarah made a swift recovery and promised to never leave Lady Betty again (with no mention of Sir William). While Eleanor was becoming increasingly frantic at the thought of being sent to France.

The Butler family agreed to one last meeting between the pair before Eleanor was to be sent off.

By all accounts it appears that Sarah’s family were totally in the dark about the women’s relationship, and although they thought Eleanor a little ‘odd’ and manly, these two women being in love was simply inconceivable. However, the Butler family were a little more in tune to what may be happening between the two women, and appear to have been ‘disturbed’ by their relationship, so offered Eleanor ‘great terms’ if she promised to never see Sarah again.12

It’s quite obvious, much like that other ‘well known’ and recently celebrated lesbian ‘Gentleman Jack’ Anne Lister, Eleanor was true to herself, and didn’t even attempt to disguise the fact that she was gay, much to her family’s horror. They knew exactly who and what she was, and what was going on, and they were determined to stop it.

Letting the Ladies have one last meeting before Eleanor left for the convent was a mistake, as the women must have hatched a plan that resulted in Eleanor disappearing again. Two weeks later she was found hiding in a cupboard in Sarah’s bedroom. Lady Betty’s maid, Mary Carryll had been smuggling her food and keeping their secret.

Sir William wrote to Mr Butler demanding he ‘remove his daughter’13. He didn’t. Both families were at their wits end, and Eleanor refused to leave Lady Betty’s house.

Finally, Mrs Goodard, privately took Sarah aside to speak to her. As mentioned before, the majority of people had no notion of homosexuality in women (only in men), it was beyond their comprehension, so for Mrs Goddard to tell Sarah that Eleanor was ‘debauched’ - which had the same meaning then as it does today - corrupt - and that she would more or less ruin her life, could indicate that even their closest friend thought Sarah was being manipulated by Eleanor.

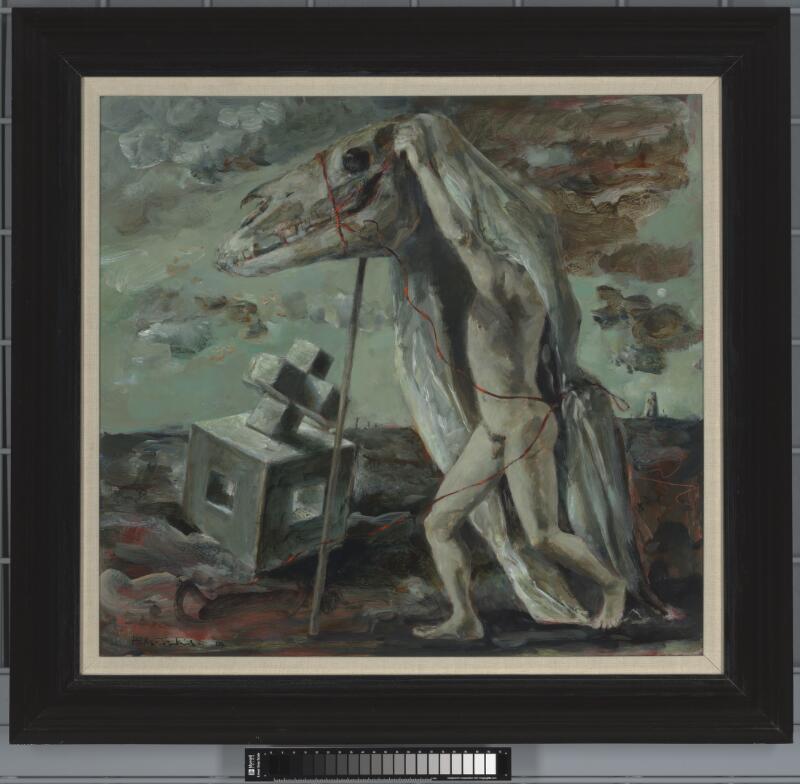

Instead of a great ‘romantic friendship’ and love story, is this a tale of a woman who was obsessed with another woman, who groomed her from childhood, and coerced her into running away to a different country? A woman who absolutely refused to stop, ever, until she got what she wanted, which was complete control of Sarah?

Even though Sarah seemed happy (or relieved?) to be back with her family, Eleanor would not let her go, ran away from her family home at the castle (remember at this time Eleanor was aged 39, she was not a young inexperienced girl), and hid in Sarah’s bedroom.

Was it love or coercive obsession?

It seems to me that Sarah could not escape. It was a choice between her guardian Sir William, or Eleanor, both pressuring Sarah to bend to their will. Was Sarah suffering some sort of Stockholm syndrome14 or was she truly in love in Eleanor?

The families finally gave in, and although there is no account of exactly what happened, one can only surmise that they both came to the conclusion that these women would continue to ‘run away’ until they were allowed to be together, it is also obvious that by now, both families knew this ‘romantic friendship’ was far more than that, to the point that when the Butler coach came at 6am to Sarah’s house to take them to the quay to set sail for England, their closest confidant Mrs Goodard, who it appears knew the nature of their relationship, and possibly of Eleanor’s ‘obsession’, adamantly refused to say goodbye to them both.

The women left in ‘high spirits’ taking Lady Betty’s maid Mary Caryll with them and they never returned to Ireland.

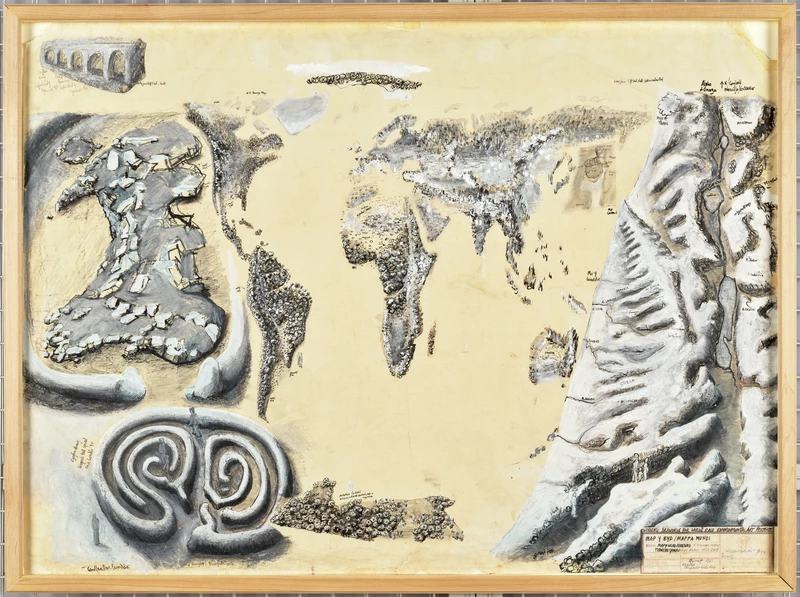

Six weeks later, both Sir William and Lady Betty were dead, probably from the stress, while Sarah, Eleanor and their maid, Mary ‘joyously’ toured Wales looking for a home.

Quite a beginning, and looking again at the lithograph, there is no hint of past scandal in this idealised drawing of two little old and rather odd-looking ladies.

This is a story that has been condensed by the passage of time into two women wanting to be together in a ‘romantic friendship’, escaping bravely like two heroic ‘pre’ feminists (with a pistol and dog), and living happily ever after, with no mention of the chaos and death they left in their wake.

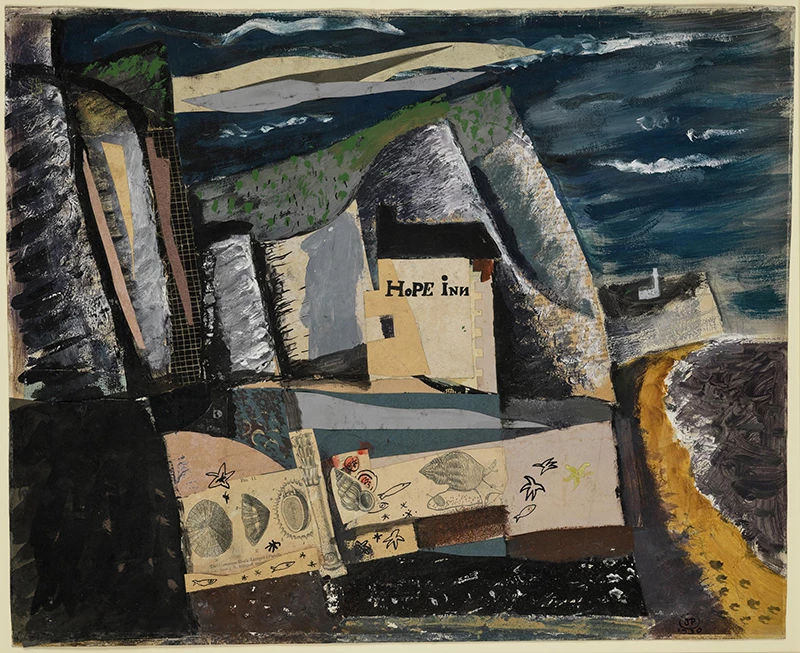

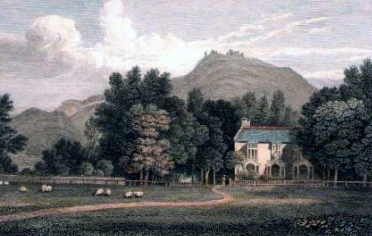

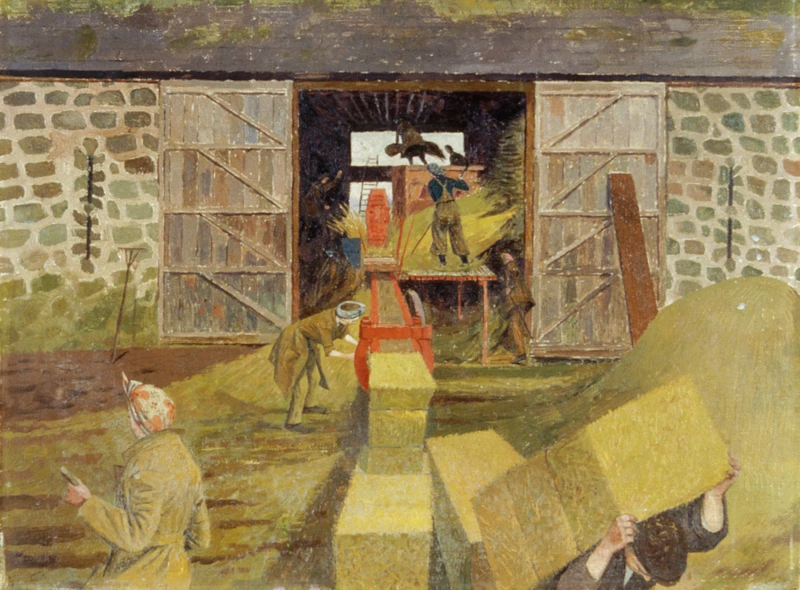

Early painting of Plas Newydd which is probably what it looked like when the Ladies first saw it. Artist unkown.

The earliest photograph of Plas Newydd, 1860 Ladies of Llangollen_website | The Ladies of Llangollen

Accessed: November 2024

After wandering around Wales and England for over six months, they finally settled in Plas Newydd15, a 2 up, 2 down (a fifth room - the very library in the lithograph was built by the Ladies in 1778) rented cottage on the outskirts of Llangollen.

They had finally got their wish, to be together, there was only one problem – money. Being ladies, they were used to living comfortably, so the £200 a year for Eleanor from her father, and the £80 a year for Sarah from Mrs Tighe (Lady Betty’s daughter) was a ‘scanty provision’16 (In 2017, £280 was equal to £28,689 17).

They spent the next fifty years writing letters to relatives, friends, acquaintances and even the royal family for financial help. In fact, Elizabeth Mavor’s book18 is, after they move to Llangollen, mostly about gardening and the Ladies’ struggle with their finances! It’s quite obvious that both Sarah and Eleanor expected to be financially kept by their families and friends19, because… well, in 2024 it’s difficult to understand why these two women would expect an affluent lifestyle just for being …themselves.

Dellangelo. The Ladies' bedroom, Plas Newydd Plas Newydd House Museum and Tearooms - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

Accessed: November 2024

We have seen the Ladies and know about their start in life together. They didn’t spend a day apart after they left Ireland, they continued to Live at Plas Newydd and Mary Caryll remained as their servant. They did everything together and shared the same bed. They lived exactly how they wanted.

Still that burning question remains. Were they one of the first openly same sex, female couples?

They always referred to each other as ‘My love’, ‘My dearest one’ and had several female friends who may have been lesbians, such as Anna Seward20. The lithograph itself shows two affluent people, who dress and look like… men, of course that does not mean they were a ‘couple’, or lesbians. But they were widely perceived to be by their contemporaries who were a little more ‘worldly’ and knew that it was possible for a woman to be sexually attracted to another woman, like the Butler family, and Mrs Goddard.

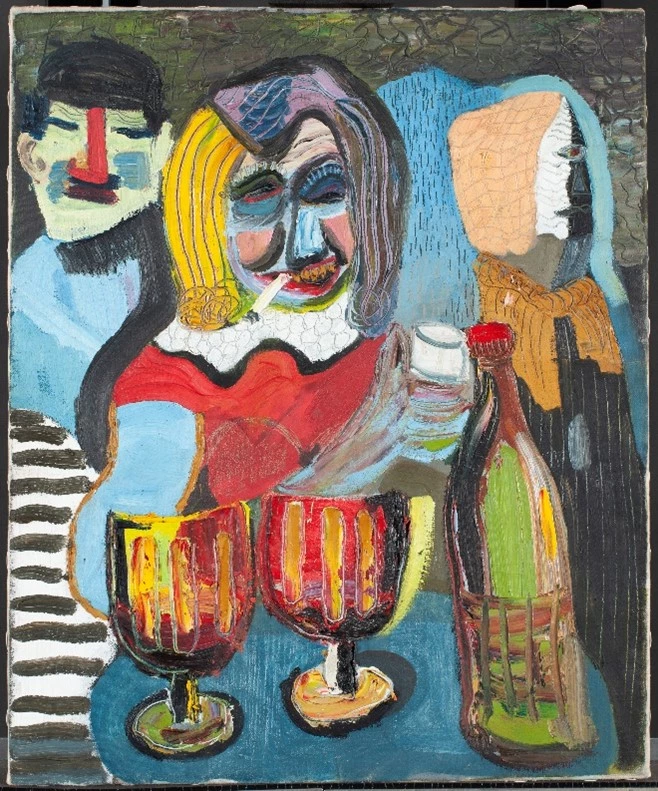

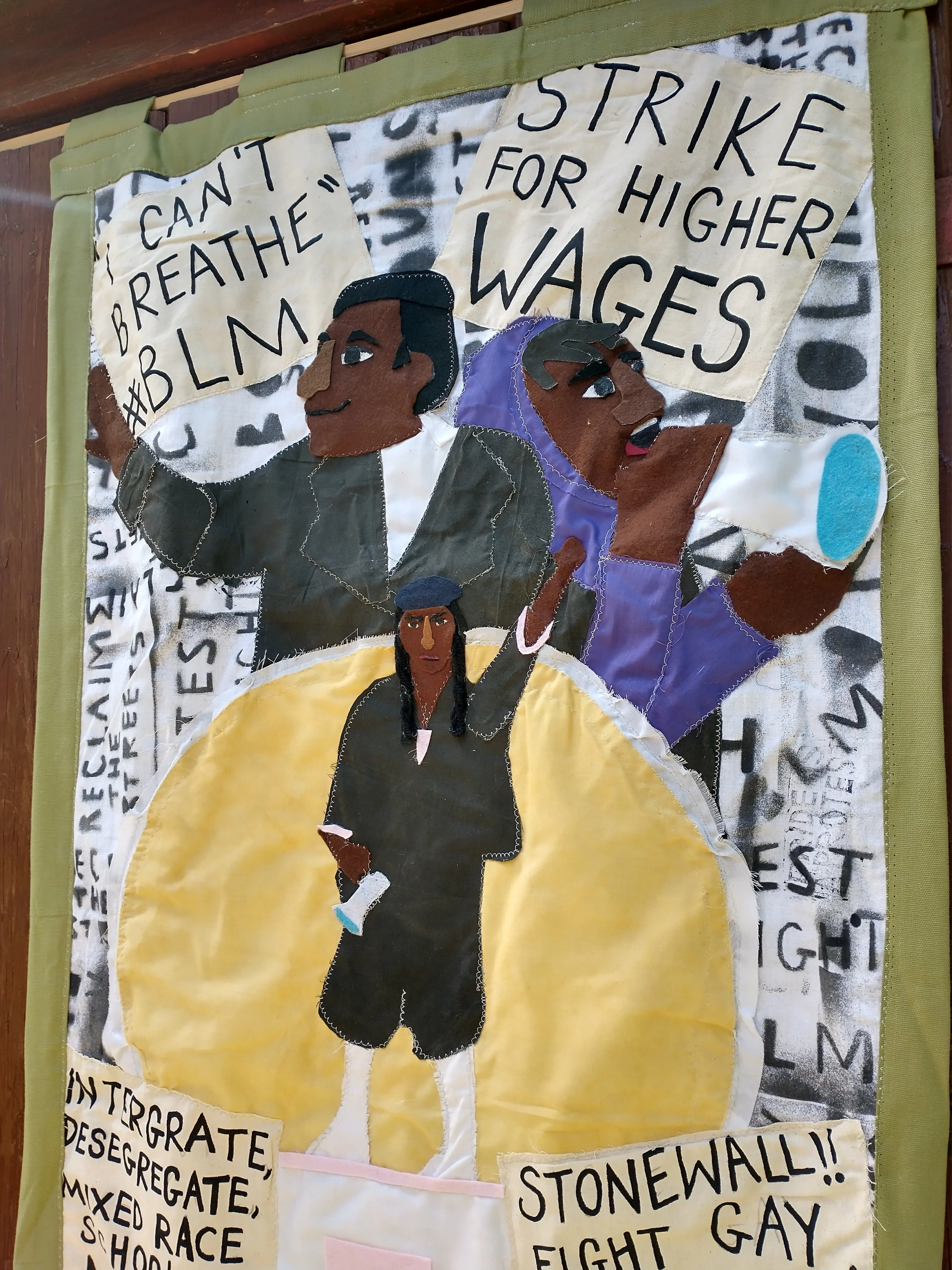

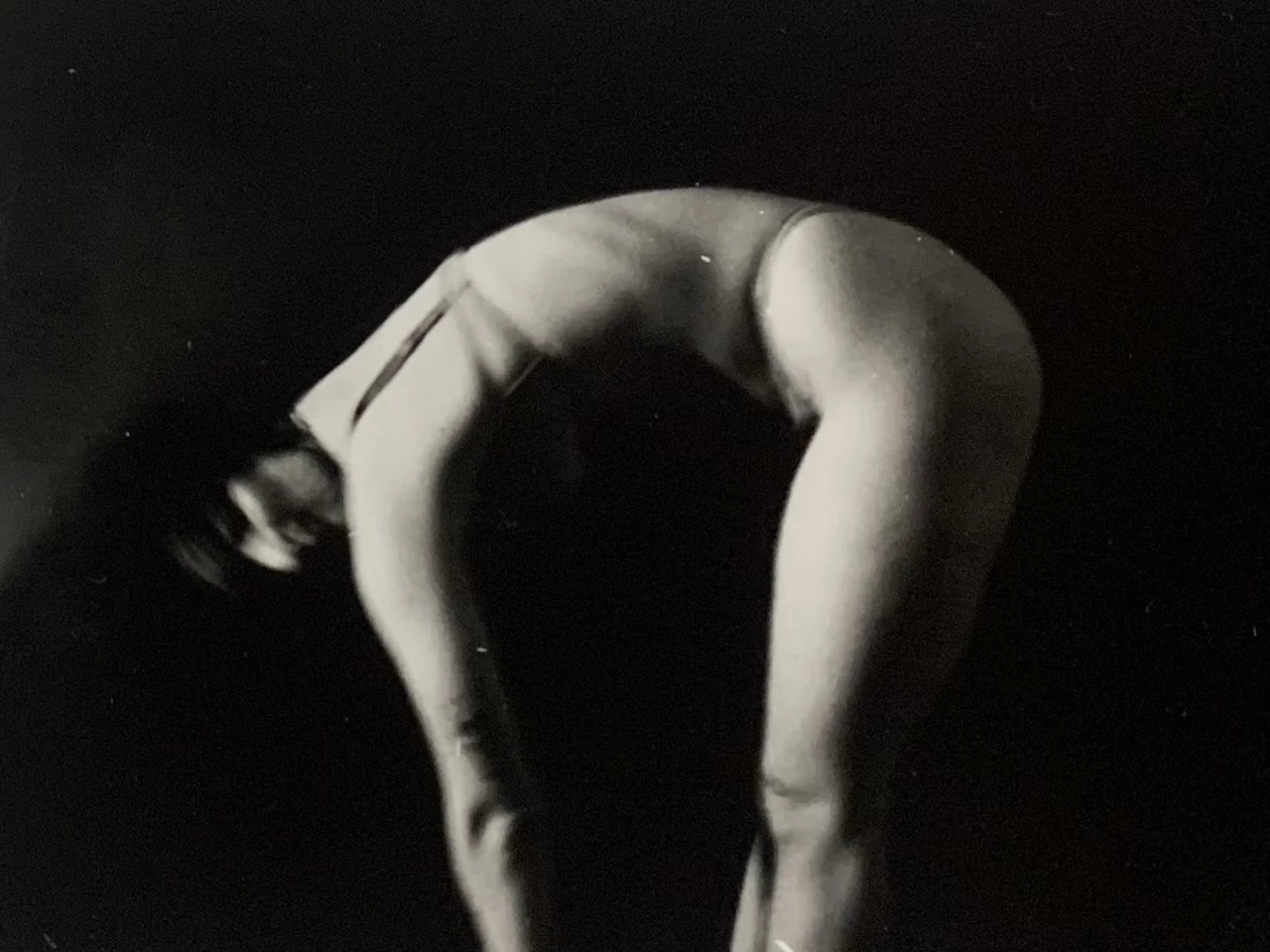

In 1790 a piece was published about them in the General Evening Post, it was called ‘Extraordinary Female Affection’ and told of their elopement from Ireland, their refusal to marry despite them both having several proposals from men, and how Miss Butler, ‘who in all respects (looks) as a young man’21 (Mavor counters this by reminding us that by now Eleanor was now rather fat aged 51), dresses and looks just like a man, is the male of the house and does all the ‘manly’ things, while Miss Ponsonby is ‘the lady of the house’.

There was, for the first time, out in the open, and in a national newspaper, an undisguised proclamation of … Lesbianism. The Ladies were a couple, manly Eleanor was the ‘man’ and more feminine Sarah was ‘the Lady’.

Eleanor was outraged, and wanted to sue, their lawyer advised them not to pursue it.

After twenty years was the (lesbian) cat out of the bag for all to see?

Personally, I have mixed feelings about the Ladies’ connection, because I do believe Eleanor may have manipulated Sarah into a relationship, she was so very young (just thirteen), inexperienced and an orphan when they met, and it does appear Eleanor’s later pursual of Sarah was unrelenting. Perhaps Sarah was flattered by the attentions of this older, unusual, aristocratic and experienced woman, who may have given her the love she was missing, a love that may have been in the beginning, more manipulation than friendship.

After the first time they ran away, Sarah seemed happy to be back with Lady Betty, despite the attentions of Sir William. Was she lying? It’s possible. But Eleanor ‘running away’ and hiding in Sarah’s bedroom, seems to be not just an act of desperation, but one of coercion. How can you escape from someone who will not leave you alone in 1768, when men owned women and coercion was unrecognised? Mrs Goodard seemed to think Sarah was being manipulated, and the fact is, we will never know the truth.

Sarah and Eleanor remained together as a ‘romantic’ couple till their deaths and beyond.

I think for me, the best way to describe their relationship is ‘Queer’. Writer Rupert Thomson perfectly encapsulates this description -

In the early 2000s one of my friends’ mothers worked at Plas Newydd and on chatting to her at the house I mentioned the Ladies being gay. She immediately became quite cross with me, and insisted they were NOT gay and just ‘romantic friends’, I was taken aback that she could feel so strongly about it. I have always felt that Eleanor was a lesbian, all the evidence points towards this fact.

ROGERS, Tina, Plas Newydd, July 2024

Nearly three hundred years later, these two small, odd-looking women in the Lithograph are now ‘queer icons’ and still of interest worldwide, they are the main tourist attraction in Llangollen and continue to be the cause of passionate disagreements between friends!.

One final thought. Throughout their years together, Eleanor and Sarah had several dogs. All of them were given one name.

Sappho.23

1 Lady LEIGHTON, (Born Mary Parker, daughter of Thomas Netherton Parker of Sweeney Hall, Oswestry, she became Lady Leighton on marrying Sir Baldwin Leighton, 7th baronet, of Loton, Salop.); Richard James Lane (Born at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, into an artistic family. His mother was a niece of Thomas Gainsborough and his father a prebendary of Hereford Cathedral. At sixteen, he was apprenticed to line engraver Charles Heath. Lane worked as an engraver for several years before turning his attention to the lithographic method of printmaking. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1824 and was elected an associate engraver three years later. Lane specialised in portraiture; he produced hundreds of portraits of royalty, actors, artists and other notable society members. Queen Victoria appointed him royal lithographer in 1837.) The Ladies of Llangollen - Collections Online.

2 A blue plate called ‘The ladies of Llangollen’ is in the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru National Museum Wales, features an image of two women on horseback set within a landscape A Story on a Plate: The Ladies of Llangollen

3 Powis Castle and Garden | Wales | National Trust

4 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 198

5 What is romantic friendship? - New Statesman

6 For more information on this law please look at Anti-Catholic Penal Laws In Ireland - Irish History

7 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 19

8 What is grooming?Grooming is a process that "involves the offender building a relationship with a child, and sometimes with their wider family, gaining their trust and a position of power over the child, in preparation for abuse." (CEOP, 2022); Grooming can happen anywhere, including: online, in organisations, in public spaces (also known as street grooming) (McAlinden, 2012). Children and young people can be groomed by a stranger or by someone they know – such as a family member, friend or professional. The age gap between a child and their groomer can be relatively small (NSPCC and O2, 2016). Grooming techniques can be used to prepare children for sexual abuse and exploitation, radicalisation (Department for Education (DfE), 2017) or criminal exploitation (Children's Commissioner, 2019). Grooming: recognising the signs | NSPCC Learning

9 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 23

10 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 25

11 Elopement meant literally running away in the 1700s rather than running away to get married.

12 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 33

13 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 32

14 Stockholm syndrome | Definition, Examples, & Facts | Britannica

15 The original name of the house was Pen Y Maes, the ladies changed it to Plas Newydd – New hall/New house.

16 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 45

17 Currency converter: 1270–2017

18 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011

19 They fell out overborrowing £50 with their closest friends the Barratts calling them ‘treacherous’ and never spoke the them again! (Mavor, Elizabeth, The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011)

20 Anna Seward - Poet, Letters, Queer Studies | Britannica

21 Mavor, Elizabeth The Ladies of Llangollen – A Study of Romantic friendship’ Moonrise Press 2011 Page 75

22 Queer theory and Rupert Thomson’s 'Never Anyone But You' | learn1

23 Sappho: Life, Major Works, & Accomplishments of the Archaic Greek Poet - World History Edu Sappho from the Isle of Lesbos was well known for her love poems to women.