New co-created Audio Descriptions are now available for you to enjoy! These two Audio Descriptions were created as part of the project The Blind Harpists: Another Look, funded by the Understanding British Portraits Network.

John Parry the Blind Harpist with an Assistant. PARRY, William © Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

The Blind Welsh Harper. PARRY, John Orlando © Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

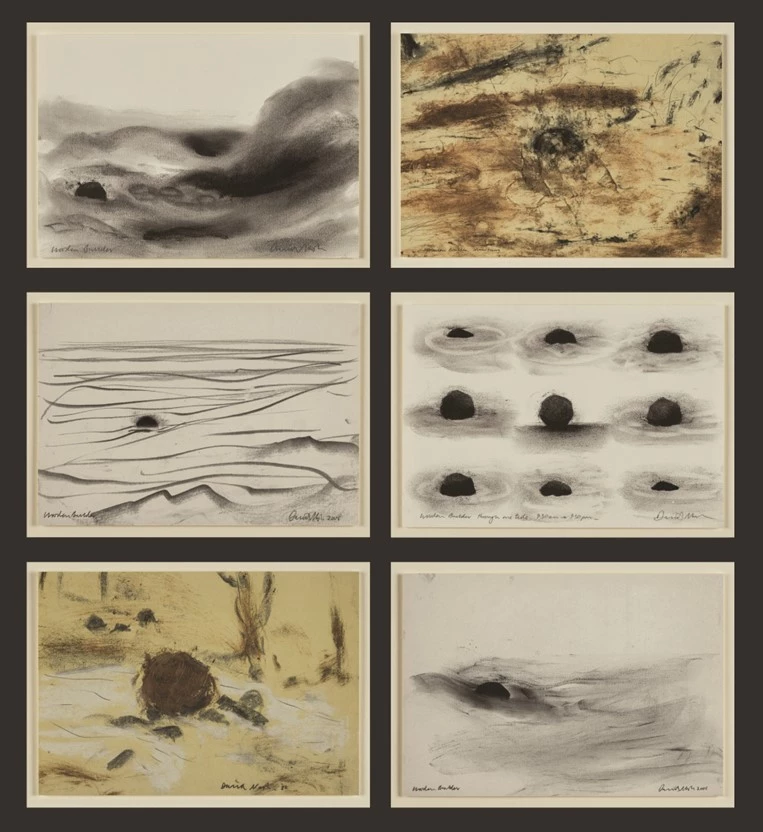

There are at least nine portraits of blind harpists in Amgueddfa Cymru’s collection. They have been in the collection for decades, but have always been written about and described from the perspective of a nonblind curator. This project took ‘another look’ by exploring two of them, John Parry, the Blind Harpist, with an Assistant and The Blind Welsh Harper, from a blind perspective. For this project, I worked as a freelance curator alongside a group of artists and contributors who are either blind or partially blind, to explore the works through conversation and observations. These conversations shaped the new Audio Descriptions below.

First off, what is an Audio Description?

Audio Description is a verbal description of an object. They act as a descriptive guide to an artwork, a prop to help people understand the material, visual, and multisensory qualities of a work. Although usually used as an access tool for people who are blind or partially blind, they can be just as interesting for nonblind people too. These Audio Descriptions are about 7 minutes long. You can choose to listen, or read the full transcript below.

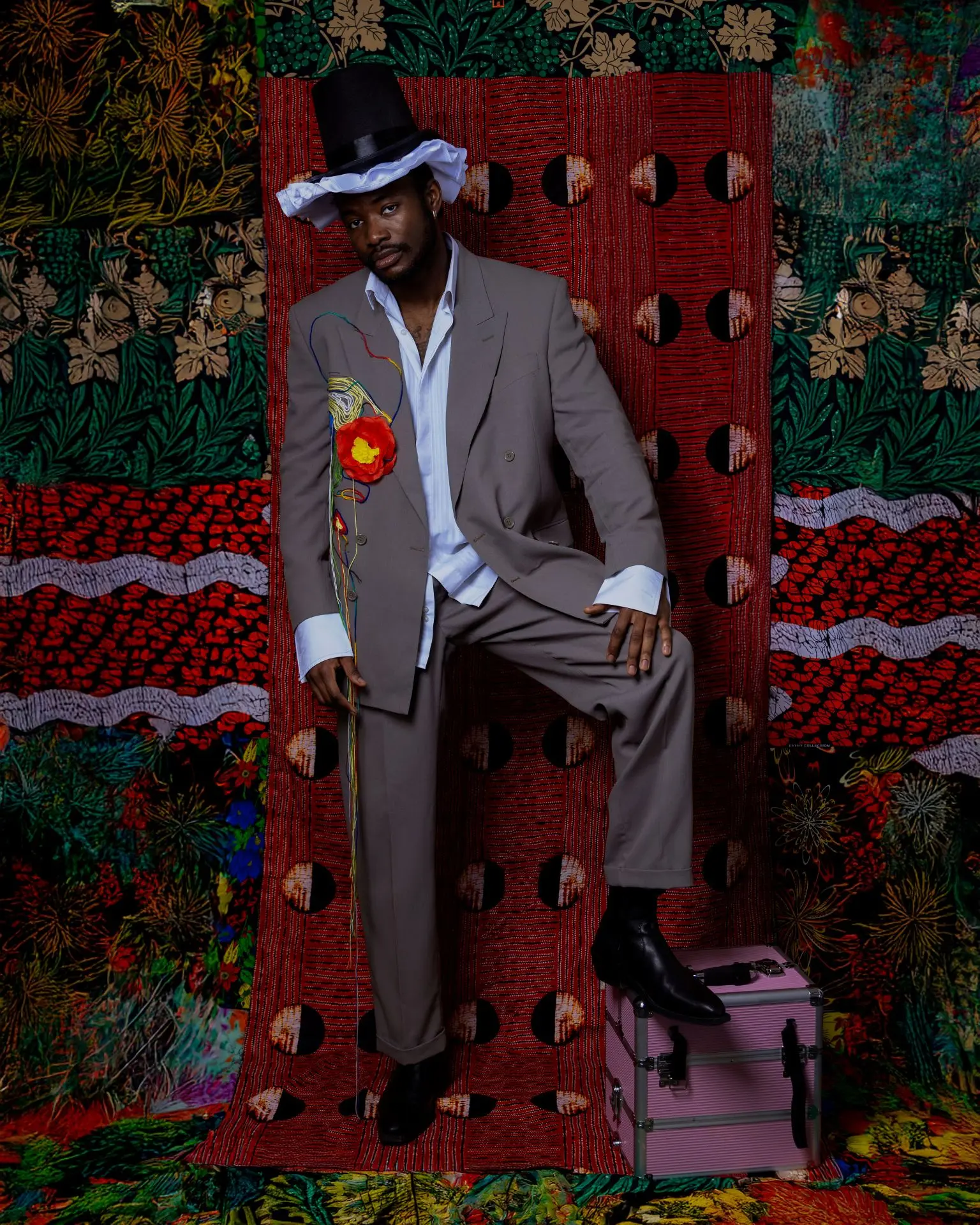

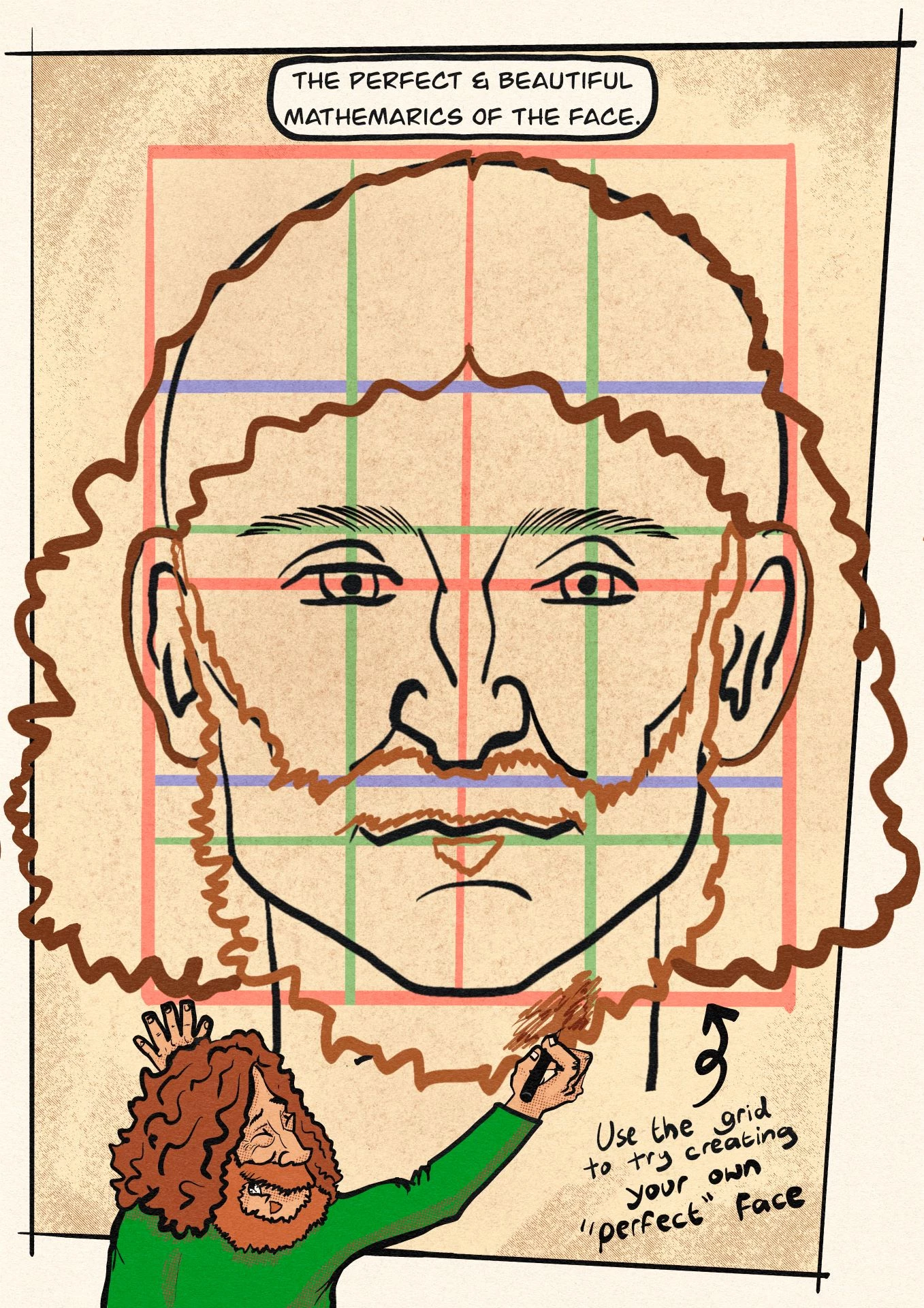

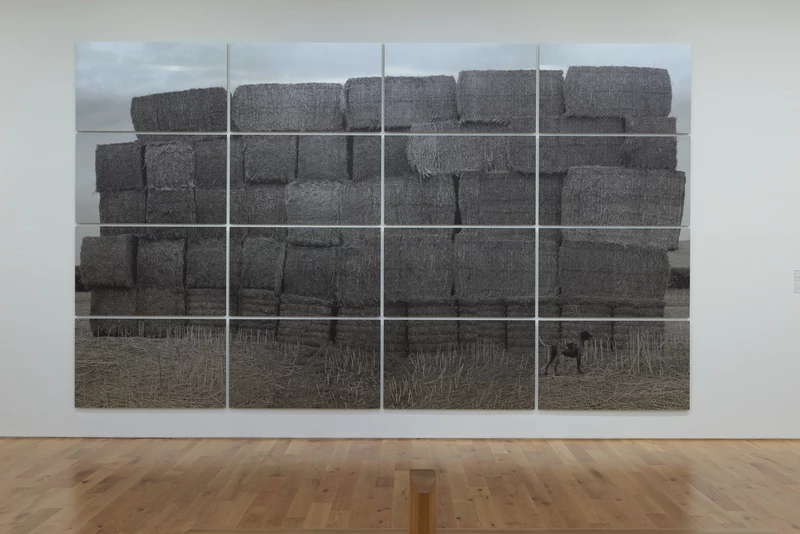

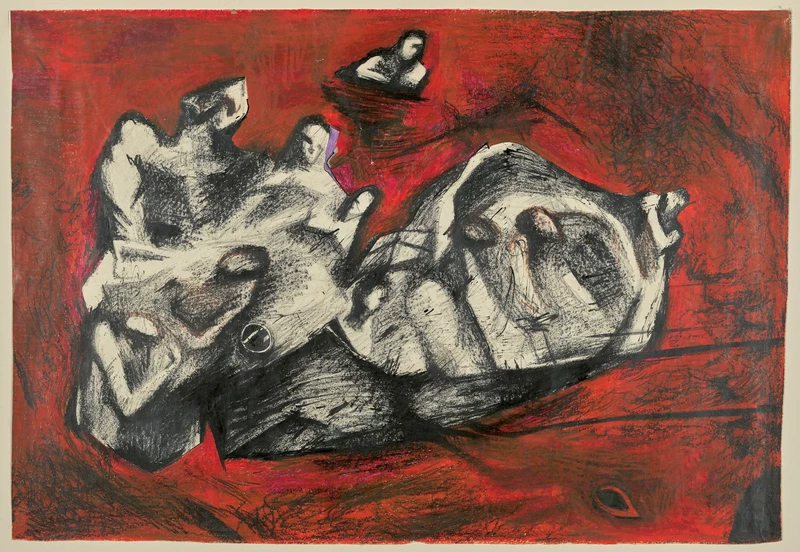

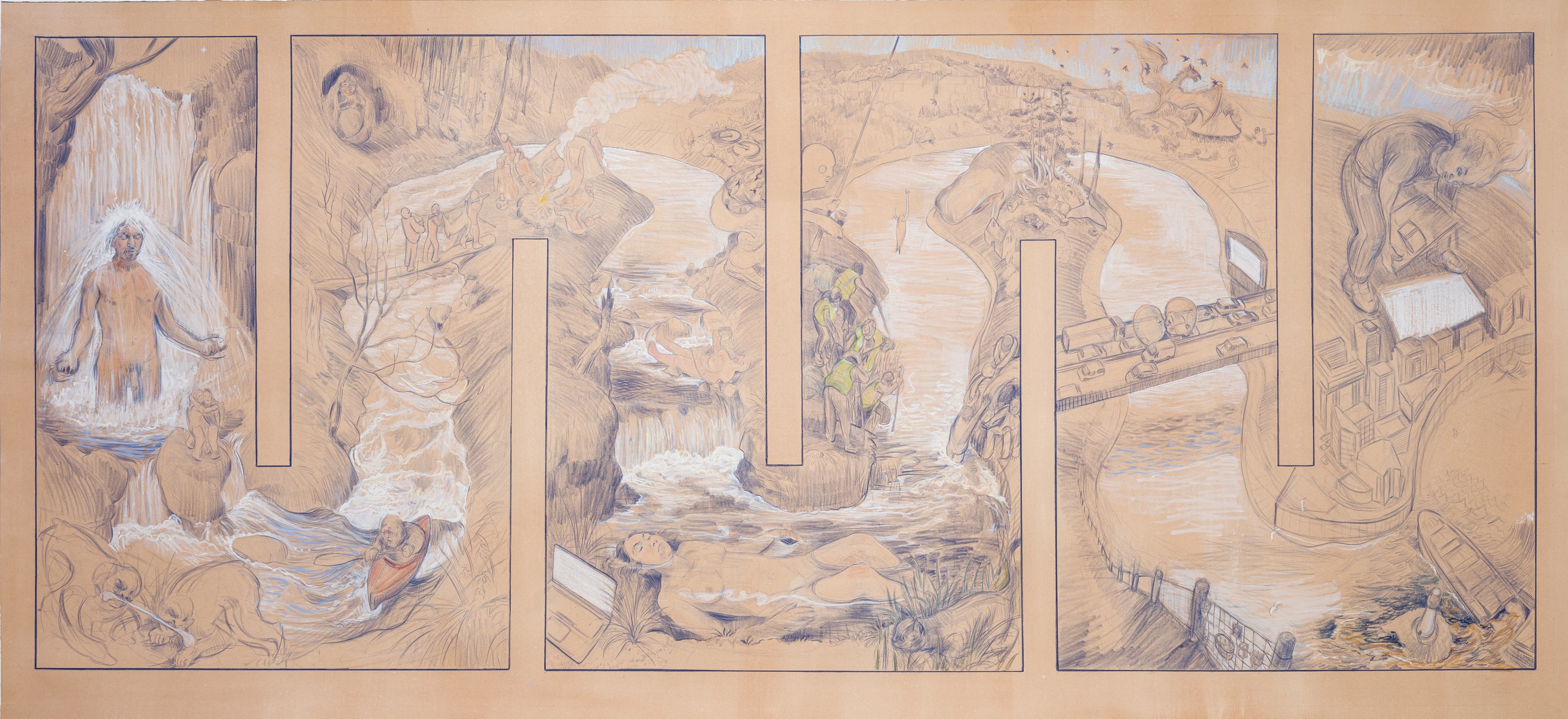

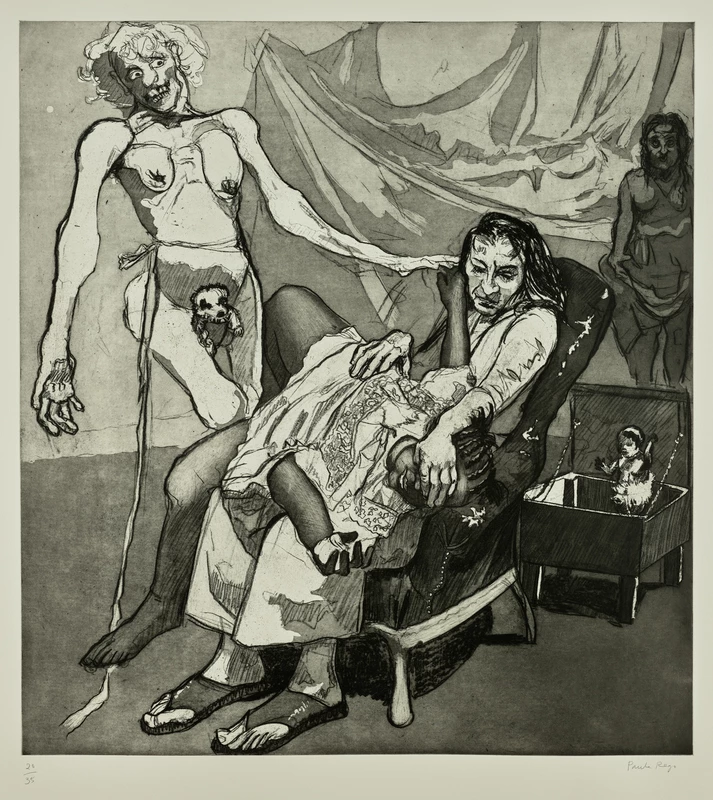

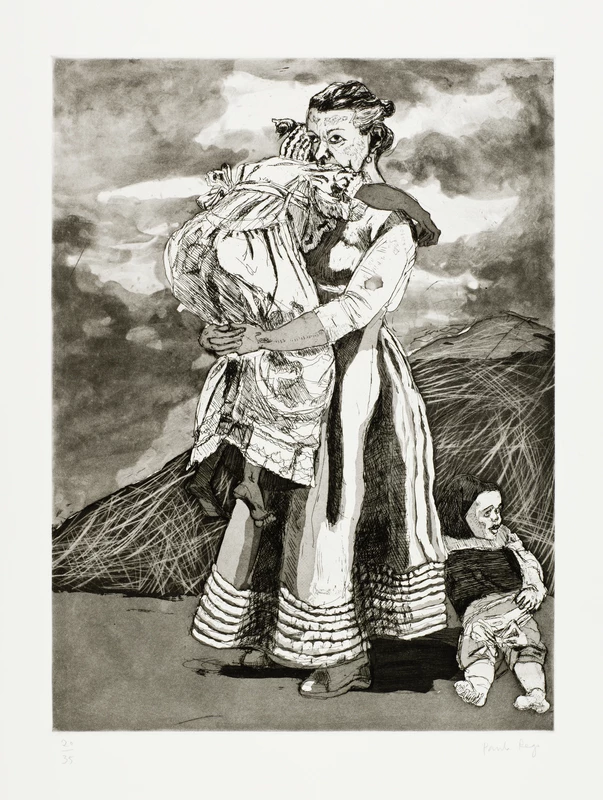

John Parry, the Blind Harpist, with an Assistant, by William Parry

This is an oil painting on canvas, measuring about 90cm high and 70cm wide. There are three characters in the painting: John Parry, the famous Blind Harpist of Ruabon; his assistant; and a harp. They are in a very dark, richly furnished room. John Parry is on the right, sat playing his harp. Next to him, on the left, is a younger man, standing and holding a musical score. He’s tilting it slightly towards us, as though inviting us to read. Listen to the audio recording, or read the transcript to find out more.

John Parry the Blind Harpist with an Assistant. PARRY, William © Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

Transcript

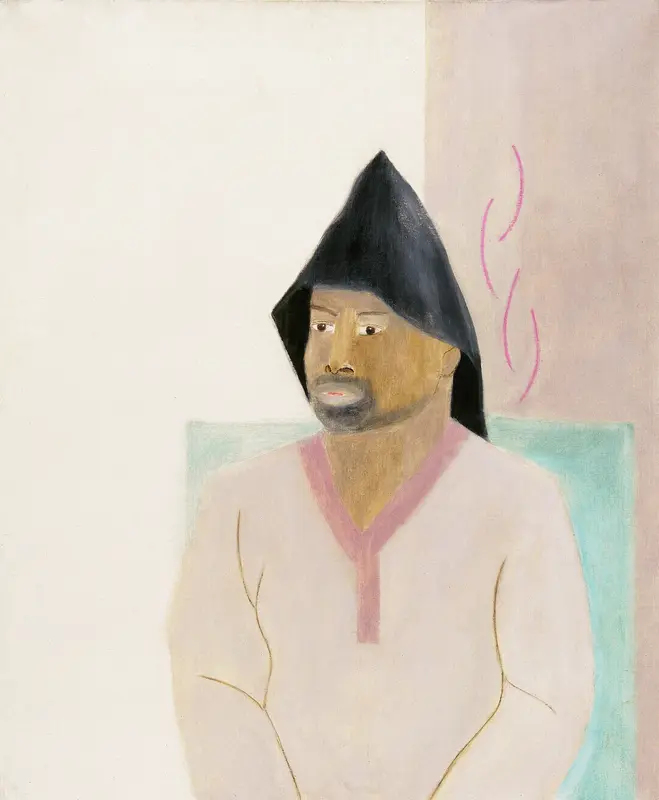

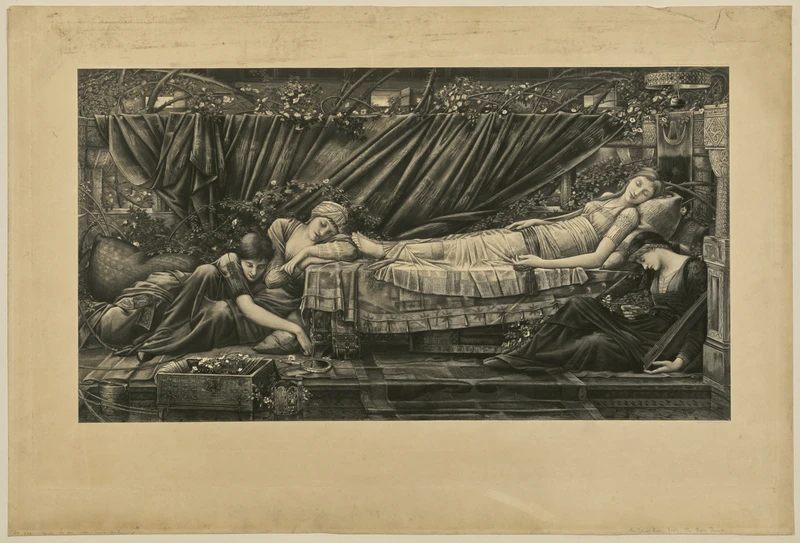

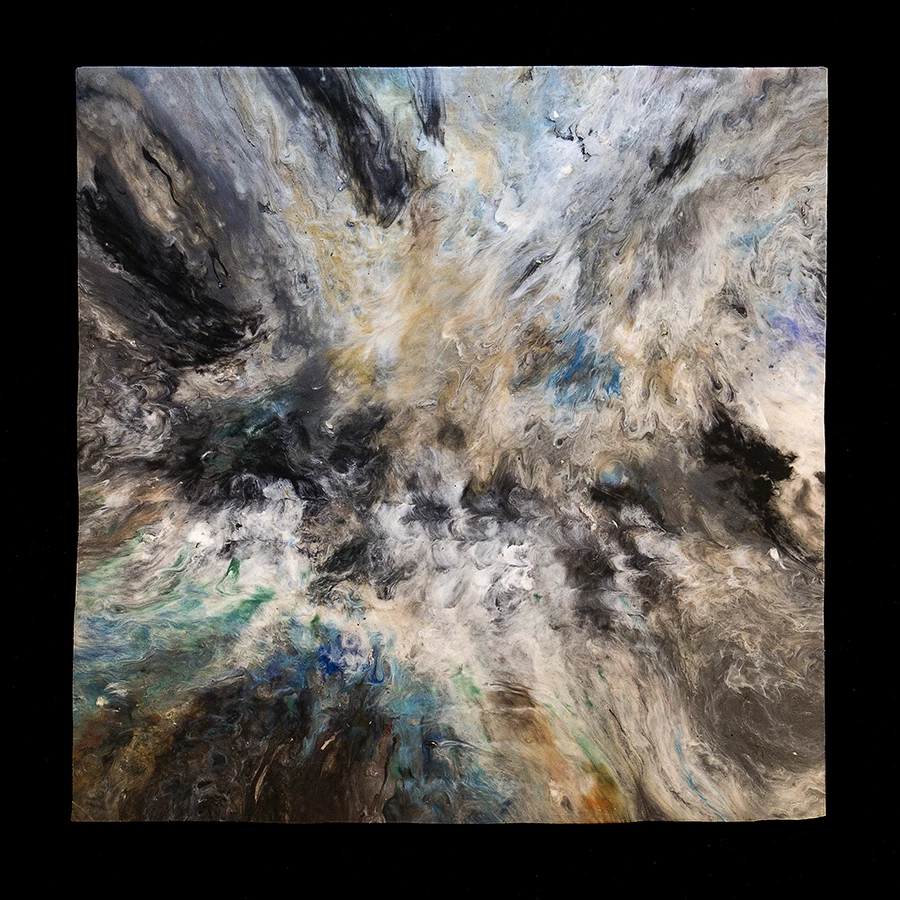

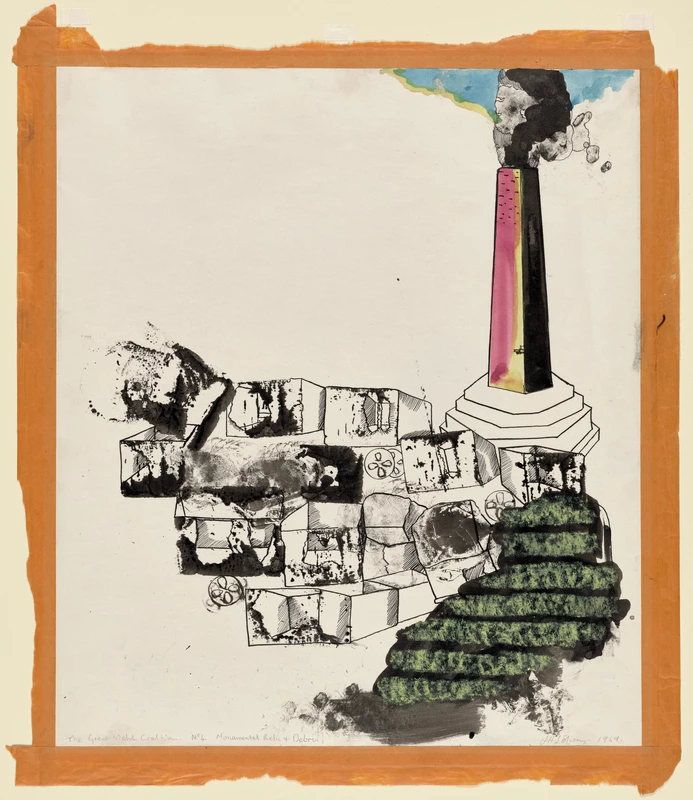

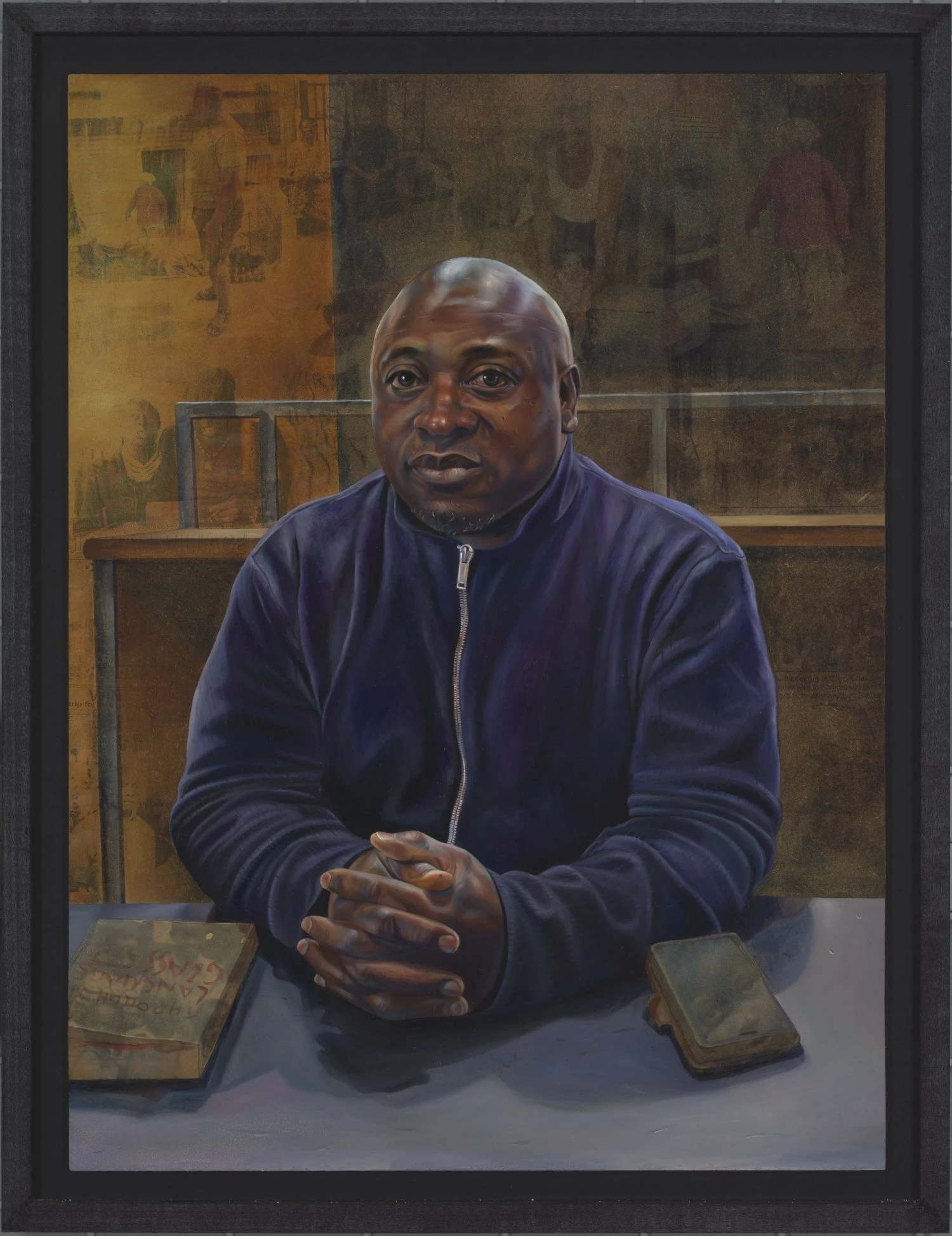

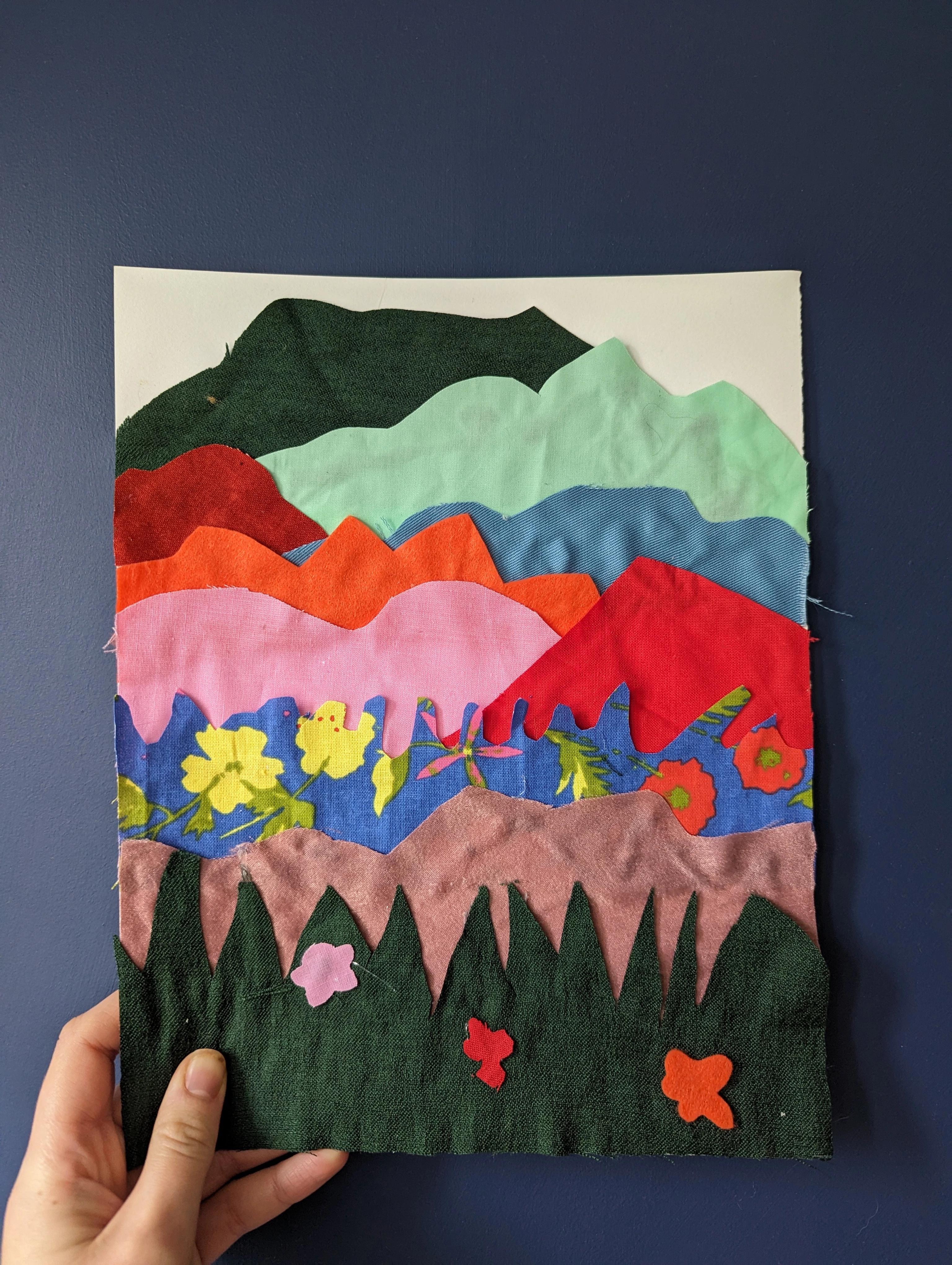

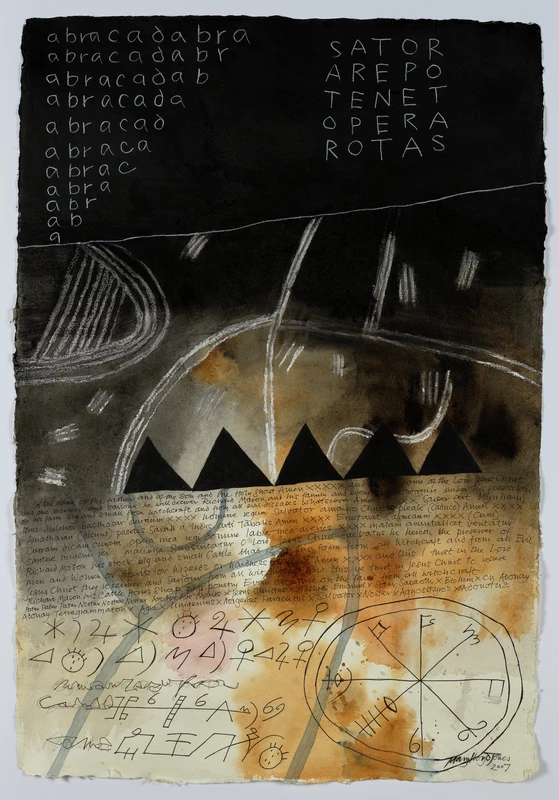

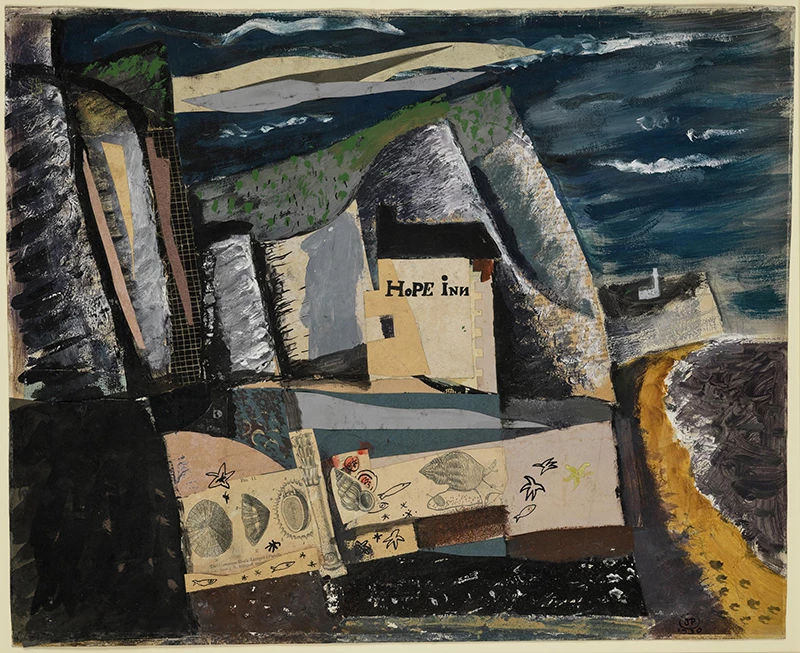

The Blind Welsh Harper, by John Orlando Parry

This is an ink drawing on paper, measuring about 50cm high and 40cm wide. The title, ‘The Blind Welsh Harper’ is written across the bottom in bold capital letters. The Blind Harper is sat on a wooden bench, facing us head on, his harp leaning against his left shoulder. He looks a bit dishevelled – his clothes are tattered and torn. He is patting the head of a shaggy dog next to his side. Under his bench is a rolled-up poster with the words ‘An Eisteddvod’ across the top. Listen to the audio recording, or read the transcript to find out more.

The Blind Welsh Harper. PARRY, John Orlando © Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales

Transcript

Putting the pieces together

This collaborative way of working questions who has the right to decide what stories get told, and how, and that the meaning of an artwork can never be contained in a single, objective perspective. As one of the participants said, ‘we all have slightly different opinions… but at the end of the day we can build up a picture. It’s like a puzzle actually. We put everybody’s little pieces together’. These new Audio Descriptions are the result of putting everybody’s little pieces together. Although read by a single voice, they represent the collective comments made by the group - Bridie, Emma, Lou, Margaret, Siân, project curator Steph, and workshop facilitator Rosanna.

Interested in running your own co-created Audio Description project?

The University of Westminster, in collaboration with the Watts Gallery and Artists Village, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, VocalEyes, and Access Smithsonian, have created a model called W-ICAD (Workshop for Inclusive Co-Created Audio Description). This model gives museums a template for working collaboratively with blind, partially blind, and sighed groups of people to co-create their own Audio Descriptions.

Steph Roberts is a freelance visual arts curator, interpreter and researcher based in Wales. Her interests include health and illness narratives, disability justice, and neglected voices in art history. She works with museums, galleries, and other cultural institutions to bring these narratives to life, and has many years’ experience developing and delivering creative Audio Described content.

Credits

The Blind Harpists: Another Look project was developed as part of a research fellowship funded and supported by the Understanding British Portraits Network, with additional support from Amgueddfa Cymru and Sight Life.

With thanks to the artists and contributors for their enthusiasm and input: Bridie, Emma, Lou and Guide Dog Taff, Margaret, Siân and Guide Dog Uri, Rebecca, and Rosanna.

The English Audio Descriptions are recorded and narrated by Alastair Sill.

The Welsh Audio Descriptions are translated by Eleri Huws, and recorded and narrated by Steph Roberts.

With thanks to the W-ICAD researchers for their advice and guidance during the planning of The Blind Harpists workshop.