A trip to St Fagans National Museum of History is often described as a trip around Wales in a day. Nowhere else will you find such an ensemble of Welsh vernacular and industrial buildings in one place, and collectively they demonstrate wonderfully how different regions of Wales developed very different building traditions. Because when you travel across Wales in real time, taking in the historic buildings, changes in materials and details emerge gradually: driving along the A5 you’ll note the meeting of enormous Dolgellau stones and Ruabon red bricks, and closer to the English border you’ll start to notice more and more black and white timber framed buildings. But at St Fagans these distinctions between regions are absolute. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than standing at the tollhouse taking in two cottages called Llainfadyn and Nantwallter, and I encourage people to read this piece as they visit and explore the cottages at the Museum.

Llainfadyn is a quarryman’s cottage built in 1762 in the village of Rhostryfan on the perimeter of Eryri. Nantwallter is an agricultural labourer’s cottage built in around 1770 in the village of Taliaris, Carmarthenshire. They were built within a decade of one another for two Welsh working-class families, yet in appearance they are strikingly different. Today Llainfadyn and Nantwallter find themselves unlikely neighbours, standing within a few meters of each other at St Fagans Museum. This article will explore the reasons for the obvious differences in their appearance and construction and how their occupants used different means and materials to meet the same demands.

First, let us consider how they are alike. In plan they are very similar: both are essentially one room, a large rectangular living space open to the rafters, albeit divided with partitions and furniture. They each have a fireplace at one end and sleeping spaces on the other. Both have cocklofts, raised platforms on which children could sleep and household items could be stored, usually open to the living room, and in both cases the space beneath the loft has been partitioned off to create a more private sleeping area. Externally, each has a façade comprising an off-centre door with tiny windows and one chimney at the gable end. You could say that both cottages have the same formula, the same placement of key features in plan and elevation, but how their builders proceeded to execute this formula couldn’t be more different.

The process of building a vernacular cottage was extremely organic, with none of the abstractions and distractions of architectural drawings. Few cottagers had the resources to employ professional designers or architects; they relied on their own skills, those of the local craftsperson, and mutual help and resources from the local community, a principle known as ‘cymhortha’.1 The obvious reason for the contrast in appearance and materiality between Llainfadyn and Nantwallter is geographical location: Wales’s topography and mountain ranges separates the country into distinct regions and historically the communication networks between these were poor. The cost of transporting materials from other regions was beyond the means of cottagers so their palette of materials was limited, often to raw material scavenged from common land nearby.

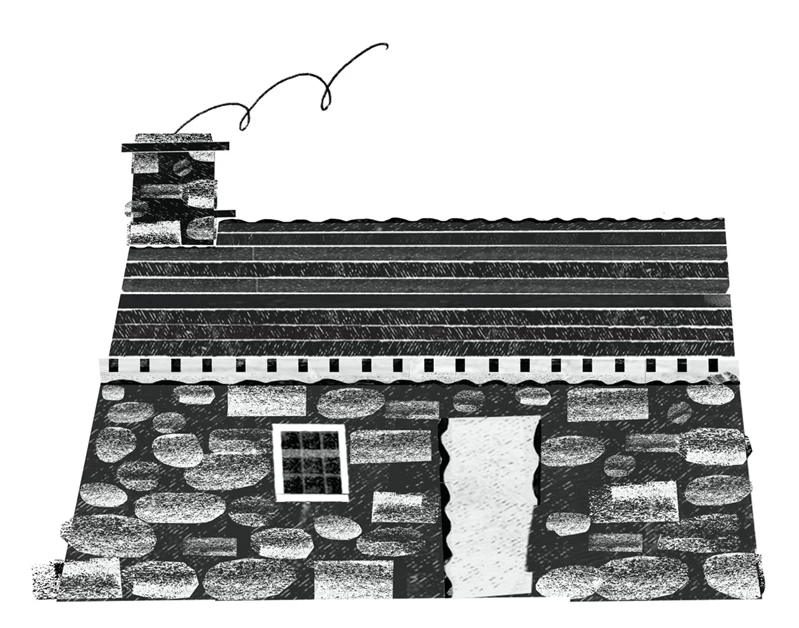

For its walls, the builders of Llainfadyn collected loose glacial boulders of granite from the fields surrounding their chosen site in the mountains. The largest, the ‘founding stones’, were often rolled into place rather than carried, and sometimes their location even determined the site of the house.2 The builder positioned each stone instinctively in diminishing rubble courses – the higher the course, the smaller the stone – to create a tapering effect externally. Some stones protrude from the walls; these are the ‘through’ stones, which help to hold the wall together. Naturally, there were deep crevices between the boulders, and these were ‘pegged up’ with stone and slate chippings to strengthen the walls further.

In Carmarthenshire, where good building stone was sparse, the walls of Nantwallter were made from clay mixed with straw and stone dust, a mixture called ‘clom’. The clom was laid in layers, or ‘lifts’, which were left to dry before the next could be added, all built on a battered rubble stone plinth, which acted as a foundation and prevented rats and mice from digging at the base of the walls. Clom construction didn’t require quoins nor corner posts, but rounded edges were created to avoid vulnerable and brittle corners. Once the mixture was dry, the square window and door openings were created, and the timber lintels inserted.

Despite the enormous difference between the undulating boulder walls of Llainfadyn and the flush clay walls of Nantwallter, the final step in their construction was the same. Both were finished with coats of white limewash, the universal way to protect from rain and nesting insects, externally and internally.

Both Llainfadyn and Nantwallter have timber roof structures covered with natural materials, but again the materials available locally differed enormously. At Llainfadyn, a layer of turf was laid on the rafters and covered with thick slates. As it dried, the turf tended to crumble and fall into the living room, so the occupants fixed a layer of calico underneath to hold it in place.3 Nantwallter’s thatched roof is made up of bracken and hazel rods laid diagonally over the rafters and a bedding of dense gorse into which the thatch was thrusted, all visible inside. It was common practice to lay bracken as soon as it had been cut and while it was still green so that it would bond into a solid mass up in the roof.4

Both sets of occupants had their means of keeping their cottages watertight. The roof slates at Llainfadyn were bulky and uneven so in order to prevent water from seeping through, fresh moss was tucked up under them from the outside. They also made notches in the boulders which acted like drips, and incorporated projecting pieces of slate, called weather-sheds, to throw water away from the junction between roof and chimney. The clom corners of Nantwallter were particularly vulnerable, so the thatched roof was raised above each corner to create eavesdrops which channelled rainwater away.

Warmth was another priority. Keeping a fire lit twenty-four hours a day was crucial to the occupants’ comfort, as was channelling the smoke out of their cottages, but again they had to approach this is varying ways. At Llainfadyn, occupants built an ‘uffern’, a pit with an iron grate into which the hot embers and ashes fell. Besides collecting ash, which was used to make cement and external paths, it also created a draft under the fire which helped draw it more efficiently. Nantwallter has a smoke hood made from wattle to draw the smoke up and out of the living room. It was lined with cow dung, considered the superior material for daubing because it resisted heat and hardened like iron.5 The gable wall of Nantwallter projects outward to form the fireplace, providing additional surfaces to absorb and store heat at the warmest part of the house. Another potential reason for this projection was the option of pulling down the chimney quickly in the event of a fire without destroying the rest of the house, and often the squat chimneys on this type of cottage would lean away from the house to divert embers away from the thatch.6

Despite having essentially one room, both cottages have internal partitions which divide the main living space from more private parts of the home, whether a pair of oak box beds to create the cockloft at Llainfadyn or the wattle partition at Nantwallter. Clearly builders and craftspeople had an excellent understanding of the properties of the materials on their doorstep, not only for construction purposes but also to create internal fixtures and fittings. The occupants of Llainfadyn used one enormous slab of slate, eight feet high and one inch thick, to create a draught partition near the door. It was common for quarry workers to erect their own little slate huts to shelter from blasts, so the occupants probably knew how to assemble slate structurally. Another way to distinguish between different areas within the space was use of different materials to create a special hierarchy. A feature of Llainfadyn which epitomises this is the tyle, a raised slate platform which runs the perimeter of the living space, on which the best oak furniture is raised away from the earth floor for to prevent decay. As well as elevating the most valuable items in the house – the long-case clock, the food cupboard, and the slate cool-storage cupboard – it also runs across the fireplace and behind the draught partition, where there is a fireside table and chairs. The distinction between slate and earth is a distinction between static spaces towards the edges of the living room, where furniture is permanently displayed and which occupants sit, and the more fluid space at the centre of the room where occupants move and use the space more freely. This tyle may be a survival of prehistoric and medieval homes, where elevated platforms such as the dais established a similar hierarchy.

The threshold is an equally significant part of both cottages, as it denotes the boundary between public and private realms and sees the most tread and wear. In both Llainfadyn and Nantwallter, the threshold is distinguished from the mud floor by a hard-wearing, smooth surface. Naturally, slate is used at Llainfadyn, but Nantwallter’s threshold comprises four stone slabs. In fact, the only stone surfaces visible at Nantwallter are the threshold and the hearth stone. Both areas see a lot of footfall and require robust surfaces, but they are also parts of the house which are associated with tradition and spirituality. Folk custom encouraged decoration of the threshold with chalk or paint for reasons such as welcoming strangers or new babies and keeping evil spirits at bay.7

These are also indicators that as well as practical considerations, occupants had aesthetic sensibilities and preferences. Efforts were made to adorn and enhance other parts of the cottages as well as the threshold, for example Llainfadyn has the date ‘1762’ carved into the bressummer above the fireplace, traditionally the heart of the home. Both families were also clearly also concerned with concealing certain unsightly materials from view; at Llainfadyn the chippings used to ‘peg up’ the deep crevices between boulders were concealed with clay daub, although later they were considered attractive and left exposed. Interestingly, the wattle partition under the cockloft at Nantwallter was given a smooth plaster finish on the side facing the living room and the entrance, but the other side which faced into the sleeping space was left exposed, the texture of the wattle visible.

The occupants of Llainfadyn and Nantwallter had the same spatial requirements, the same wants and needs, yet the cottages they produced are opposites. Now they have been brought together to stand side by side, they are testament to how rich and varied the architecture of Wales once was. They demonstrate perfectly why St Fagans National Museum of History was created, to help us appreciate the historic vernacular buildings of Wales in a modern, globalised society where identical houses are built in Caernarfonshire and Carmarthenshire, or indeed anywhere in Britain. The reason I encourage people to read this piece whilst visiting the cottages at the Museum, rather than including photographs, is that because of the existence of the Museum we needn’t rely on old photographs or historical accounts of either building to study and enjoy them today.

Notes

1↑ Martin Davies and Dawn Jay, Save the Last of the Magic: Traditional Qualities of the West Wales Cottage (Carmarthen: Martin Davies, 1991), p. 6

2↑ H. Harold Hughes and Herbert L. North, The Old Cottages of Snowdonia (Bangor: Jarvis & Foster, 1908), p. 31

3↑ Eurwyn Wiliam, The Welsh Cottage: Building Traditions of the Rural Poor 1750–1900 (Aberystwyth: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales, 2010), p. 25

4↑ Eurwyn Wiliam, Home-made Homes: Dwellings of the Rural Poor in Wales (Cardiff: National Museum of Wales, 1988), p. 13

5↑ Iorwerth C. Peate, The Welsh House: A Study in Folk Culture (London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1940), p. 183

6↑ Wiliam, The Welsh Cottage, p. 202

7↑ Wiliam, The Welsh Cottage, p. 208

Further Reading

- Barnwell, Rachael and Richard Suggett, Inside Welsh Homes/Y Tu Mewn i Gartrefi Cymru (Aberystwyth: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales, 2012)

- Davies, Martin and Dawn Jay, Save the Last of the Magic: Traditional Qualities of the West Wales Cottage (Carmarthen: Martin Davies, 1991)

- Hughes, H. Harold and Herbert L. North, The Old Cottages of Snowdonia (Bangor: Jarvis & Foster, 1908)

- Lowe, Jeremy, Welsh Country Workers Housing 1775–1875 (Cardiff: National Museum of Wales, 1985)

- Peate, Iorwerth C., The Welsh House: A Study in Folk Culture (London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1940)

Bethan Scorey is a building historian and illustrator from Cardiff. She initially studied architecture but, inspired by her summers spent as a Museum Assistant out in the historic buildings at St Fagans, she decided to pursue a master’s degree in Building History at Cambridge University. As part of her master’s, she returned to do a student placement in the History and Archaeology department. Bethan is currently studying for a PhD at the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates with a project about St Fagans Castle, and continues to work as a Museum Assistant out in the buildings on the weekends