ash (wood)

ribbon

cotton (spun and twisted)

They came from the east, originally. Then they came north out of Europe, driven by a changing climate, finding space in existing communities until they became established. They are distinctive, recognisable, have their own characteristics. There are now nearly as many of them in the British Isles as there are people.

The ash tree is both an element of a habitat and a habitat in itself. It forms part of woodland communities: most woods will have an ash, and they will grow in wet or dry conditions. They barely need soil at all. According to Oliver Rackham, ash is the food plant of 111 species of insect and mite, 600 species of lichen grow on its trunk, 26 mosses and four liverworts are associated with it.

The ash, too, is a useful tree. It burns green, unseasoned. Although of low status, its wood was used in carts, wheelbarrows, ploughs and harrows. It was favoured for tool handles, rakes, spear shafts, walking sticks. The leaves were used to feed cattle in winter, when the grass does not grow. The Morgan Motor Company still grows ash to make the frames for its cars.

The List of Historic Place Names maintained by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales lists 245 entries featuring the word onnen. These refer mostly to fields where particular ash trees may have been obvious features. The 19th-century song Llwyn Onn is well-known in Wales: wandering by a “lonely ash grove” a man finds his lover, but, despite the singing blackbird and the flowering bluebells, he is consumed by thoughts of parting. “What are the beauties of nature to me?” he asks.

The ash, then, is part of the human habitat, as much as it is part of the natural environment. So much so, in fact, that Ronald Hutton suggests that it was regarded as the “most arcane of trees” with “more superstitions recorded about it in folklore collections from the British Isles than any other species”.

The 18th-century naturalist Gilbert White recorded “rupture ashes”: when an infant suffered from abdominal rupture, an ash was split and the child passed through it. The split was then bound-up and plastered. As the tree healed, so would the child. The practise is recorded in Hampshire, Cheshire, Cornwall, Devon and Herefordshire: at Walterstone the child was passed through the split nine times and the tree bound with withies. White also recorded a disease in cattle supposed to have been caused by shrews running over the animal. The cure was to bore a hole in an ash and wall up a live shrew inside it. Twigs from the tree were then stroked over the affected cattle as a cure. A shrew ash, bent into a sideways-Z, was photographed in Richmond Park at the turn of the 20th century. It finally collapsed in the Great Storm of 1987.

The Richmond Park tree was also used in a ceremony supposed to cure whooping cough. Afflicted children were passed under a “witch bar” inserted into the tree whilst a woman known as a shrew mother would recite words timed with the sunrise. An even stranger tree was recorded in Oaker Coppice, Eyton, Herefordshire. This was covered in human hair, inserted into the bark. The belief that hair from a child with whooping cough placed on the tree would cure the condition carried on into the 19th century, when people from the village living in London would send locks of hair to the local game keeper to place in the bark.

Ash trees were said to attract lightning, their branches to repel snakes. Placed under a pillow, the leaves of the ash would give the dreamer prophetic powers. Finding an even-numbered ash leaf (like a four-leafed clover) was lucky and foretold true love. The seeds (known as keys) were hung over doorways to deter witches and pickled were said to be an aphrodisiac, a cure for jaundice and a preventative of flatulence. The sap was considered a general tonic and given to new-born babies. But the magic could work both ways. In Cheshire in the 19th century, ash canker was thought to have been caused by people rubbing their own warts with bacon and inserting it under the bark of the tree as a cure. The tree then “caught” the warts.

Grid Reference SN6351032910

Old County Carmarthenshire

Community Talley

Type of Site TREE

Period Post Medieval

In Wales the ash has a wide distribution, but is densest in the south and south-west. Oliver Rackham notes the presence of the trees in the ex-industrial valleys of the south, where they have taken hold since the 1930s. Wales is also the location of the largest recorded extant ash in the British Isles. The girth of the trunk of the Talley Abbey Ash in Carmarthenshire was measured in 2010 as 33 ½ ft (10.2m). Larger trees have been recorded, but not since the 19th century.

The ash at Talley is in a hedgerow a short walk from the remains of the medieval abbey. From a distance it’s hard to grasp the true dimensions, but looking up from underneath, some of the lower branches are the size of individual trees. About four metres from the ground an alder grows from the trunk: a hawthorn grows from another limb. The tree is moss and ivy covered, some of the horizontal branches mottled with lichens. Water collects in small hollows and twists in the trunk, overflowing to run down the bark. Celandines grown in a nook. The bluebell lined tarmac path which runs along the bottom of the tree is being pushed up and broken by its roots.

It came from the east, originally. From Asia and into Poland then (officially) reaching the UK from the Netherlands. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus probably arrived in the 1970s and was first recorded in Wales in 2012. By 2016 the Welsh Government described it as “well established” across Wales and banned the import and internal movement of ash trees, plants and seeds. It spread quicker than the models suggested and slowing it down is “no longer considered to be feasible”. The fungus fruits on the ground, releasing its spores which land on leaves, enter the tree and disrupt the water transport system within. Leaves wither and blacken, lesions appear on the bark, the crown dies back, the tree becomes susceptible to other diseases and pests. It is estimated that the fungus will kill up to 140 million of the UK’s ash trees, costing up to £15 billion pounds to the economy.

carried in silken bag

as a cure for fits (children)

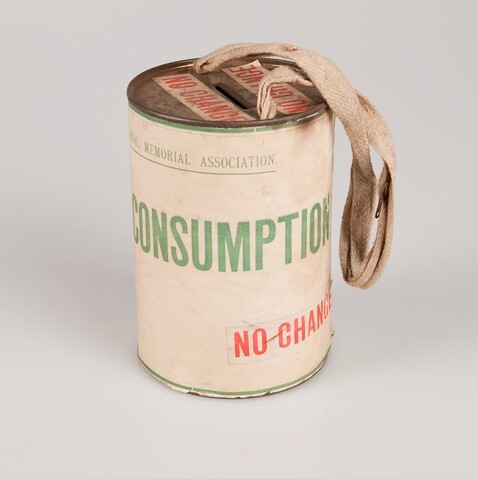

Item Number 11.24.7 in the collection of Amgueddfa Cymru comprises two twigs of ash: a thicker one, cut at both ends, just below a budding leaf. The other twig is the end of a budding branch, a black bud at the tip. With these is a leaf, the petiole and lower two leaflets are present, the remaining leaflets have been removed. The twigs and leaf are tied together with a red thread, wrapped around five times and tied in a double knot. One end of the larger twig, opposite to the leaf bud, is split and a leaf stem has been pushed into it. A loose leaf is also present, but it is uncertain what this was attached to. It may have belonged to the leaf stem in the split end of the larger twig. The bound twigs and leaves were all carried in a bag made from red silk, stitched with red cotton and sealed with a drawcord of red ribbon.

The object is a strange one, and unusual as a cure for “fits” (epilepsy). Elsewhere, folkloric cures are odd and convoluted (for example: beg twelve pennies from twelve different people, exchange them for a shilling, send it to a silversmith to be made into a ring which, when worn, will cure the fits), but in Herefordshire mistletoe tea was considered beneficial, as was tying rue to the hands, wrists and ankles of an affected child. Epilepsy was often associated with possession and witchcraft. Perhaps the ash, with its apotropaic properties, was seen as a suitable material for repelling the perceived cause. A bunch of ash keys, tied together with a red thread, are in the collection of the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Cornwall. Carried in the hand, or tucked into the top of a left stocking, these were said to protect from harm by witches. The Horniman Museum houses a similar object, again tied in a red thread and with a silk bag. The Horniman collections also include ash twigs, most of them in bud, for boiling in water which, when drunk, was a cure for fits.

It came from the east, originally. From China into France, Germany and Finland, then the UK. Orthocoronavirinae was confirmed as present in Wales on 28 February 2020. The virus causes respiratory tract infection in humans, affecting the sinuses, nose, and throat; the windpipe and lungs. This can lead to pneumonia, respiratory failure, heart problems, liver problems, septic shock and death. The most severely affected areas in Wales were in the south-east and Swansea Bay. Governments across the UK banned movement by, and interaction between, people. For the first time since the 16th century, the border between England and Wales was patrolled, preventing movement across it. Over 128,000 people in the UK have been killed by the virus, the current estimated cost to the economy £300 billion.

Trees and people, lives tied together with a red thread. The healing of one, the health of another. Inhabiting shared habitats, protecting each other. And yet Oliver Rackham suggests that since the 1970s as many introduced tree diseases have appeared as in all of the years before. He blames globalisation, allowing the circulation of new pests and diseases in areas outside of their natural range. Globalisation, too, allowed the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2, but does not appear to be assisting the deployment of vaccines to the areas of the world which need them most. In 2004, the World Health Organisation concluded that “globalization appears to be causing profound, sometimes unpredictable, changes in the ecological, biological and social conditions that shape the burden of infectious diseases…” Zoonotic infection (between animals and humans) was a major concern: these often being the result of humans moving into new habitats and becoming exposed to new viruses. Climate change, too, is forcing animals to move out of their usual habitats and to come into closer contact with humans, again creating the opportunity for pathogens to find new hosts.

The beliefs behind the object given the Item Number 11.24.7 in the collection of the National Museum Wales date to a period before globalisation, before medicine as we know it came into being. Before vaccines and before anti-epileptic drugs. But perhaps there was an understanding that the human and the non-human are interconnected, that the non-human had properties which went beyond the strictly utilitarian and functional. Beyond what may now be considered the rational. But perhaps these old practices serve as a reminder that we are intrinsically tied-up with the organisms with which we share the planet, that we sever the red thread at our peril.

- Ronald Hutton. Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Wiley. 2010.

- Ella Mary Leather. The Folk-lore of Herefordshire. Logaston Press. 2018.

- Marylin Mason. Magic in the Park. (Accessed May 2021.)

- Oliver Rackham. The Ash Tree. Little Toller. 2014.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. List of Historic Place Names. (Accessed May 2021.)

- Lance Saker, Kelley Lee, Barbara Cannito, Anna Gilmore, Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum. Globalization and infectious diseases: A review of the linkages. 2004. (Accessed May 2021.)

David Mullin is an archaeologist, potter and writer based in Herefordshire. His main research interest is the archaeology of borders and borderlands, and he completed a PhD on the prehistory of the Anglo-Welsh borderlands in 2011. His writing is informed by the landscape of the borderlands; the relationships between people, places and things and the ways in which the past is present in the present