Two revelatory encounters occurred as I worked on this edition, both completely life enhancing. I share them here with the full permission of everyone involved.

Early on, I asked Lisa Edgar, Deputy Keeper of Art, if anyone at working for the National Museum might have a story to share that fitted the theme of arts and health. Lisa introduced me to Sharon Ford and Jade Fox. Jade is a museums assistant in Cardiff and Sharon is Learning Participation and Interpretation Manager at the Big Pit National Coal Museum. I met them individually in the way everyone seems to meet these days, on a screen. I thought I’d write about their projects separately, and then, half drifting into sleep, I realised they belonged together within the framework of a paper written many years ago by the British Paediatrician and psychoanalyst, Donald Woods Winnicott in 1953, ‘Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena: A Study of the First Not-Me Possession’.

The scope of Winnicott’s paper is broad – mothering, infants, holding, separation, relationships and play - he actually described his own approach to research as one of gathering ‘this and that, here and there’ (Winnicott in Phillips, 2007: 16), but its central theme, an appreciation of what Winnicott named the ‘transitional object’, persists to this day. I’m only going to reference this and his thinking about play in this short discussion.

Winnicott describes the newborn as existing in a space where, in its first few weeks, all its needs are met – the mother (not necessarily the birth mother) is totally committed in her adaptation – and the infant lives under the illusion of ‘oneness’ with the mother. Over time, the child finds something else, a soft thing – ‘a bundle of wool or the corner of a blanket’ (Winnicott, 1953: 91) – which comes to function as the first ‘me and not-me’ object, and marks the emergence of self as subject. This object functions as an intermediary or bridge between the infant’s internal and external world and is ‘a defence against anxiety’ (Ibid: 91) that can persist into childhood and beyond; indeed, Winnicott tells us that it may reappear ‘at a later stage when deprivation threatens’ (Ibid). We can easily see the transitional object at work in a baby’s life. Soft toys that become constant and never to be left behind companions. A well-worn blanket that is always needed on journeys or for sleep. The same blanket that must never be washed and consequently develops its own special aroma. Linus, the blanket worrying character in the Peanut’s cartoon offers a perfect example of the transitional object or ‘Linus blanket’ in action, Winnicott’s ‘defence against anxiety’. What Linus shows us is the importance of the familiar. This returns me to my meeting with Sharon and another theory-in-action, that of continuing bonds.

Sharon tells me about the National Museum’s social media project, Objects of Comfort which invites people to respond to the museum’s on-line collection through prompts shared twice a week on twitter and Facebook, one of which is shown below. This prompt – of quilts and blankets and softness, protection and warmth – returns me to thoughts of Winnicott, reminding me that need for a ‘defence against anxiety’ persists well beyond childhood. It’s something Becky Adams has also recognised in her learning resource on quilt making. Sharon’s response to the prompt, an image of her Nan’s yellow biscuit barrel nestled alongside a teapot, milk jug and tea caddy, reminds us that comfort is to be found in many things, including shared rituals such as enjoying tea and biscuits – remember Proust’s lingering memory of the ‘little crumb of madeleine’? Sharon’s story is as much one of continuing bonds, a living and performed connection with someone loved and physically gone through objects, as it is about comfort itself, this is the very stuff of social history.

The Object of Comfort project has been extended into nursing homes across Wales. At a time when they are closed off to all but essential visitors, it is a creative and very real attempt to maintain social bonds through shared activities and, it seems, some playfulness. Responding to the ‘Tea’ prompt, Penybont Nursing Home described discussions about the changing nature of tea, watching tea adverts on YouTube and the discovery of what, at £660, might well be one of the world’s most expensive tea pots.

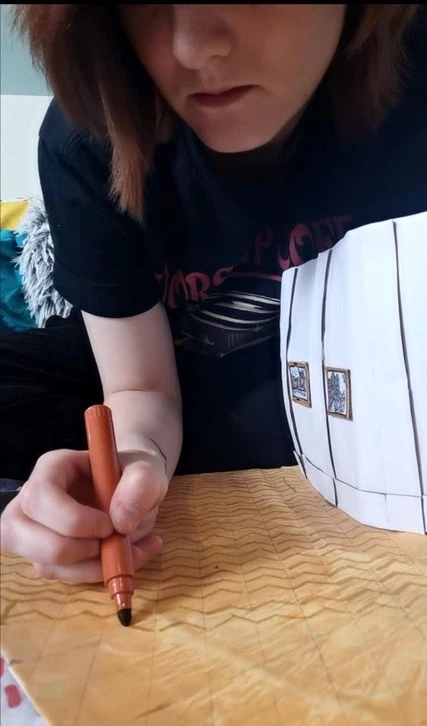

This playfulness brings us to Jade. She works front of house at National Museum Cardiff and loves her job, especially engaging with visitors and being ‘with’ the collection. Being furloughed was a huge challenge for Jade. She is open about her long term experience with depression and anxiety and worried that the isolation of lockdown would have a very negative impact on her well-being, she tells me that she did spend some time feeling she had nothing to get up for. One of Jade’s friends shared a Facebook post of someone who had built a 3D model of Tate Modern, as if for a hamster, and suggested Jade might do something similar. Rising to the challenge, Jade refigured the in-between space of furlough isolation. She revisits her childhood creativity, making a series of remarkable, infinitely engaging 3D models of the museum. Jade holds one up to the screen, the museum’s café area. I had sat there only days before lockdown, sharing tea and welsh cakes with a close friend. This moment of recognition is bittersweet, because simple things are no longer, well, that simple. But the sweetness, that comes instinctively in the squeal of joy that spontaneously leaves my body. They are fabulous. They make me laugh, and I realise I haven’t responded to anything like this for weeks. Jade’s models, made from this and that, the scavenged and repurposed – made out of necessity and not unlike Winnicott’s own making - are life affirming. I ask her to tell me what they mean for her,

I can honestly say, without a doubt, that if I didn't have these models I would be in my bed not wanting to move and going down a dark hole. My models are the reason I get up in the morning, they have brought me so much joy.

Looking back over the experience of guest editing this journal, of encouraging others to share their personal stories of arts and health and well-being, it is these two small events, of connection and playfulness brought about through the circumstances of where we are, what we must all endure, that seem to speak to me so meaningfully. Neither one is likely to have come into being outside of this time and both are perfect testimony to our individual capacity for creative resourcefulness. Sharon and her team returning to loved objects to weave new stories. Jade making her own meaning in the space of furlough, a space Winnicott might have recognised as the intermediate area of experience, which has a ‘direct continuity with the play area of the small child who is ‘lost’ in play.’ (Ibid:96) And me, happy to have discovered both.

- Phillips, A (2007) Winnicott London: Penguin

- Winnicott, DW (1953) Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena, a Study of the First Not Me Possession International Journal of Psychoanalysis vol 34, 1953, 89-97.