I am a disabled person and a disability writer and artist based in North Powys. I preface the word ‘disability’ before ‘writer and artist’ as I feel that it is very important to align myself with the political stance of disability activist and the social model of disability, which states that it is not our impairments which disable us, but societal barriers and structural discrimination. There is a subtle distinction between a disabled artist and a disability artist. An artist who is a disabled person is a disabled artist; a disabled artist whose work is concerned with disability issues is a disability artist. My writing and artwork inevitably involves a disability position; as a disabled person navigating an ableist society my life is reflected in my art. Even when I’m painting a landscape or an animal portrait, my life experience filters through.

My writing has always explicitly expressed mental health issues, but I wasn’t aware when I first started painting that my visual art had anything to do with my mental health and physical impairments. However, as time progressed, disability issues started creeping in, and I allowed this to develop, trying different ways of expressing the issues in predominantly non-representational art. I use colour and shape to convey ideas and emotions. My artist self was ‘born’ in Wales, back in 1992 when I was using mental health day services and was first encouraged to try visual art, after not doing art since primary school. I use the artist name Ceridwen Powell to reflect my adopted Welshness. I write under the pen-name Rosamund McCullain.

I am also co-ordinator and a member of Celf-Able, an inclusive art group in Montgomeryshire. We are 100% disabled-led and disabled-run, showing that disabled people can have agency and not just be passive recipients of services, but are able to organise and provide services for both themselves and the wider community.

What I find particularly striking is the almost total absence of disabled people in art; either representations of disabled people by non-disabled artists, and, even rarer, work by disabled and/or disability artists. Much research has been done into the absence of female artists in art galleries and the art canon, and indeed it is shocking that there are so few women artists in the major collections. The Guerilla Girls, founded in 1985, use provocative text, visuals and humour in the service of feminism and social change. They have written several books and create projects about the art world, film, politics and pop culture. They travel the world, talking about the issues and their experiences as feminist masked avengers, highlighting injustices and inequalities, not just of gender discrimination but in wider society. The academic Griselda Pollock, feminist art historian and cultural theorist of art practices and art history, challenges mainstream models of art and art history that have excluded the role of women in art, and at the same time explores the social structures that result in this exclusion. She examines the interaction of the social categories of gender, class and race. But little research has been carried out into the representation, as subjects and artists, of disabled people in art. I have just commenced a PhD with University of Leeds which will explore and research this very issue.

I am hoping to have a better time with University of Leeds than I did with another university where I did an MA in Fine Art from 2017-2019. I shared with them my access requirements at interview, and prior to enrolling, I had Disabled Student’s Allowance in place to meet my access requirements, but the university just couldn’t seem to grasp what was required of them. It took them 18 months to provide me with a suitable chair. On the first day, I was presented with a steep flight of stairs and a longish walk to the library, and I had to stand at the top of the stairs and say ‘I’m sorry, I can’t come’ to the group. This experience prompted the first painting I did whilst a student, ‘How It Feels When People Or Situations Disable Me’, which I displayed prominently in my studio space so that everyone would get the message. But even more than physical barriers, I had to fight the attitudinal barriers. I had been clear that my interest was disability art, but there was no space in the curriculum for me to pursue my interest, and the tutors really did not ‘get’ my artwork, to the point that my degree piece, ‘DWP R.I.P.’ was altered between me setting it up and the degree show opening. I have heard similar horror stories from artists who attended other universities. The disability art aesthetic is not necessarily the same as the institutional art aesthetic, but trying to change the way artists express themselves to fit with some notion of ‘norm’ robs disabled and disability artists of their voice.

A group of prominent disability artists has just published a manifesto, ‘Not Going Back To Normal’. In it Nelly Dean comments,

Arts organisations treat Disabled and Deaf artists differently – they don’t see our work as quality, they don’t understand the politicalness of it. They judge it as inferior. That needs to change.

Since 2010, austerity policies have cut welfare and the services upon which disabled people rely, costing many thousands their lives and setting back hard fought for disability rights decades. Disabled people see the threat that things will deteriorate for us even further with the Covid situation, and disabled and disability artists have rallied significantly, launching the ‘We Shall Not Be Removed’ campaign. There was a social media action day on Wednesday 17 June when disabled artists from across the UK celebrated the depth and diversity of inclusive & disability art on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, using the hashtags #WeShallNotBeRemoved and #EndAbleism. The campaign was designed to raise awareness of the magnified inequalities for disabled people working in the creative industries caused by the pandemic, as many disabled artists face long term shielding, loss of income and invisibility in wider society.

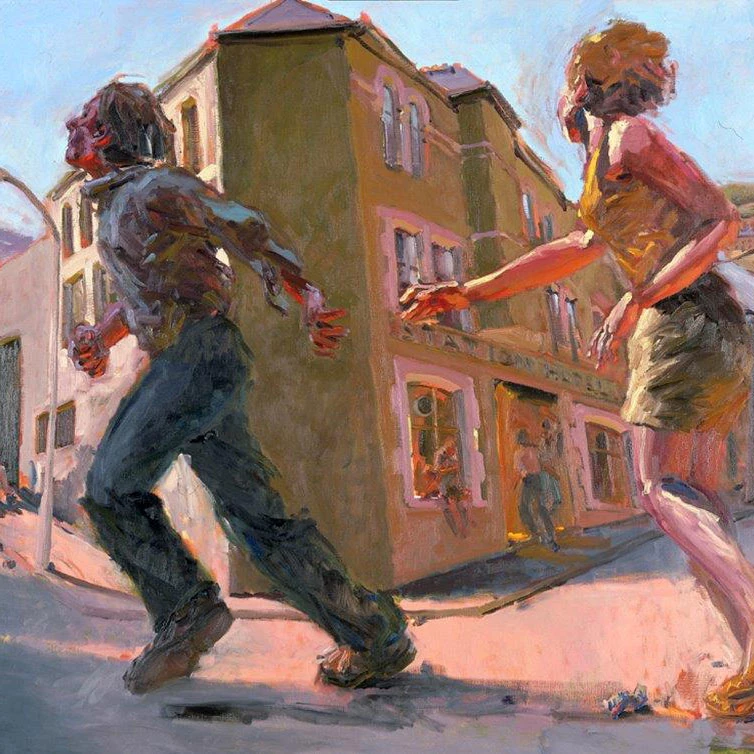

Ceridwen Powell How It Feels When People Or Situations Disable Me, 2017 acrylic on canvas

So, then, exploring the National Museum Wales collections, what is to be found? Using the search term ‘disability’, most of the results come up in the social and cultural history category. There are antique prosthetics, notably false arm attachments worn by John Williams of Penrhyncoch, who was wounded in one arm during the First World War. The various adaptations include a hook, a hammer, and other attachments which were presumably designed to enable Mr Williams to continue working. As there was no Welfare State, disabled people still had to earn an income in whatever way they could. In a similar vein, there are dolls made by the Vale of Clwyd Toy Factory in Trefnant, which provided employment for wounded soldiers during and after the First World War. There is a necklace and a decorative buckle made as occupational therapy by Corporal Walter Stinson of the 11th Battalion County of London Battalion (Finsbury Rifles) when a patient at the St Fagans Red Cross VAD Hospital during the First World War.

The collection also includes some clothing belonging to Hopcyn Hopkins, or Hopcyn Bach, who was born with a form of dwarfism in 1737. At the age of 14, Hopcyn was taken to London by his parents and publicly exhibited for money. Billed as “the wonderful and surprising Little Welchman”, in 1751 Hopkins was presented to the Royal Family who gave him a gold watch, an annual pension and ten guineas for each appearance he made at Court. In the same year, he was also ‘on display’ in Bristol. He died aged only 17.

This behaviour of exhibiting disabled people as curiosities, for money, was not unusual. The Bethlem Hospital, or Bedlam as it became better known, was in a way a kind of tourist attraction, with visitors paying to come and gawp at the ‘lunatics’. The inmates of the hospital would play up for the visitors, in order to be thrown pennies. These social attitudes persisted for well over a century. The National Museum Wales collection holds a poster for Edwards and Page’s Electric Picture Pavilion in Ystradgynlais, who in 1912 were showing ‘Elroy The Armless Wonder’, who could play musical instruments, shoot and paint with his feet.

In terms of fine art, the only works in the collection are the paintings of Pete Jones from Bangor. Upon graduating from art college, Jones found it difficult to earn a living as an artist, and became a learning disability nurse at Bryn-Y-Neuadd hospital in Llanfairfechan for many years. Jones has painted portraits of residents at the hospital, based upon archive photographs and visual memory; these were exhibited in his first major solo show, ‘Mordaith’, at Oriel Ynys Môn in 2019. He said that he wanted ‘to capture the humanity and integrity of some of the people who lived (and died) in the hospital, many without families, and whose very existence would have been unknown to many.’ The portraits are painted with a kind of respect and tenderness that the hospital’s residents may well not have experienced in their real lives. My personal favourite of Jones’s paintings in the collection is ‘5 Orange Chairs’, which depicts five figures sitting on orange institution-type chairs. The figures are barely delineated, as if they are being swallowed or erased, and the central figure has his mouth open wide, letting out a scream that no-one can or is willing to hear. It is worth noting that Jones’s work is categorised as Social and Cultural History, and not Fine Art.

The inclusion of Jones’s work in the collection is to be welcomed, as at least there are some works depicting disability in a dignified and respectful manner, but it is still a long way from having work by disabled and disability artists in the collection and on show. It may be that some of the artists in the collection were disabled but had not declared this or felt it not significant to their work. Henri Matisse, for example, developed arthritis in his hands in later life and could no longer paint, so adapted his work by making cut-out artworks, which have since achieved iconic status. Whether he considered himself to be a disabled person is not known, as the definition is a more recent development.

Searching other major collections reveals a similar paucity of representation of disabled people, and work by disability artists. Tate have some work about disability issues and have worked with Shape Arts, DaDa and Disabled Avant Garde. The disability-led arts organisation Shape Arts, which provides opportunities and support for disabled artists and cultural organisations to build a more inclusive and representative cultural sector, delivers the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive, which documents the Disability Arts Movement, which began in the late 1970s and continues today. It involves a group of disabled people and their allies who broke down barriers, helped change the law with the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995, and made great culture and art about those struggles.

For current artists, there are online opportunities such as Outside In, which provides a platform for artists who face significant barriers to the art world due to health, disability, social circumstance or isolation, to display and sell their artwork. DaDa, Shape and Outside In all offer various opportunities for disabled artists to have their work exhibited. There does seem to be a greater openness developing for disability artists, certainly I find myself regularly submitting work to a variety of opportunities. Turner Contemporary recently had a commission opportunity specifically for disabled artists. Through persistent effort, disabled and disability artists have got a foot in the door of the major institutions. Networks such as Disability Arts Cymru, and Disability Arts Online support, encourage and inform disability artists. There is a growing sense of self-belief amongst disability artists that our work is important, significant, aesthetic and every bit as deserving of gallery space as any other work.

To conclude then, there is some progress in the opening up of the mainstream art world for disability artists. Disability artists are passionate about and committed to their work, and this will carry us forward into the future, until there is a truly inclusive art world. There is a long way to go, and it will take a great deal of determination, but disabled people are used to having to be determined just to navigate everyday life, so I am sure that as artists we will continue to apply pressure and force that door open wide. National Museum Wales could even be proactive here, and commission work by Welsh disabled and disability artists, to set an example for other public organisations in Wales to follow.