ACT1 - Day 1

20:30

20:30

I have rocked to a natural stillness. The sway in my movement has stopped and I can feel the autonomic processes shifting within me. A roll of bowel grumbling. The dry tackiness of my soft palate. When was the last time I had something to eat? More importantly when was the last time I had something to drink?

Work always reminds me of the sea. I have loved the coast. It is the constant dynamic change of the coastline that draws me to it each season. I have long left clock pieces behind. I instead have learned to track time from when last I felt the small grittiness of sand between the webs of my fingers, crook of an elbow, a smatter in the outside creases around my eyes. I am always surprised by how new it always feels. I have marked my life in the summers my skin has basked in.

The hospital corridor I find myself in, is painted a deep blue till my mid chest height. On some days I pretend to hold my breath to walk through until I get to a shallower end. Some days I am so deep boned breathless that I feel I have escaped a drowning.

I have wondered what it must be like to be a patient. In a bed drifting on some mechanical raft through to CT, Xray, MRI, Stroke Ward, Lift 3, Theatres, Ultrasound. Drifting in and out of sub-delirium.

The porters the rowers.

The nurse the rudder.

An IV line like a masthead

Onwards.

Onwards.

Reaching to the inevitability of some shore.

ACT2 – DAY 4

04:45

A night bitten dawn glides through the shuttered blinds, blinking open through the hospital chapel windows. I have come to rest for a few movements. This stillness sits more sure-footed. I have found myself on several break-of-dawns here.

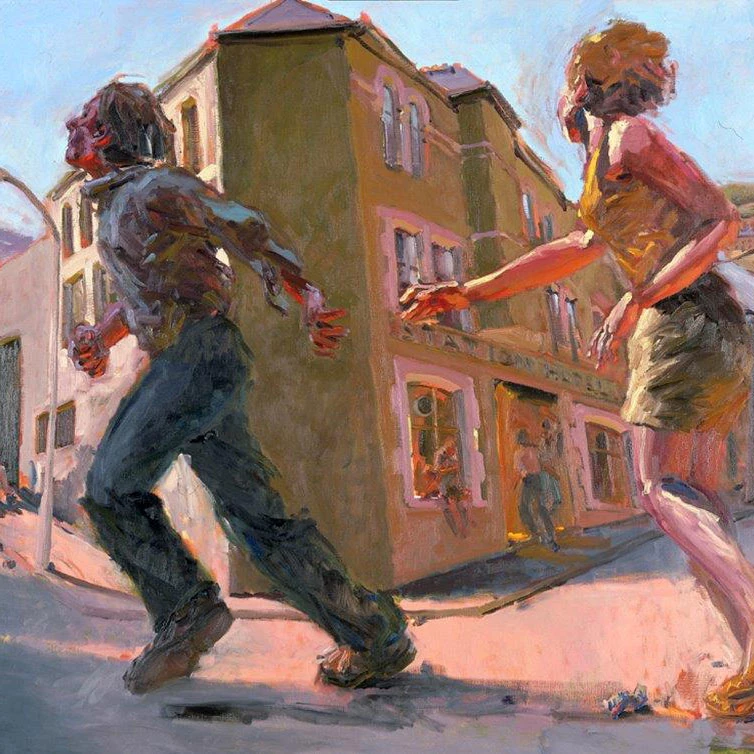

I make my way to the open prayer book at the lectern and start reading. The dance of hope and terror in medicine is best shown here.

There is the chill of a summer night’s dew seeping through the double glazing and it meets my bare arms as I turn each page. Counting the number of entries since I last was here. I feel like I am prying into them by reading. But I read anyway.

I do not know who they are. People do not leave their names. There is a quiet finality to the warbling handwritten ink on paper. Giving blessings. Asking miracles. Requesting peace.

The last stanza of poet and radiologist Danie Abse’s “X Ray” echoes through my mind whenever I'm here. There is a desperate terror of when we have to humanise our objectiveness. I have learnt to breathe through each gut-punch piece of evidence we collect. This is a deeply necessary terror.

I know I will never forget the first person I knew would die by the end of the day. The way you just know. The way the thought slides to sit heavy in your stomach. It’s something they can’t teach you.

There have been 9 entries since my last night shift.

Is it strange how sometimes a single book can feel more human.

ACT3 - Day 3

Rest.

I have driven myself to the coast today. In the distance I can see each ebb and sway of Bracelet, Limeslade, Langland, Caswell bays. I convince myself that just beyond the next one, just a bit further I’ll see Rhossili.

Rest.

I have come at the rise of dusk. I need to switch my sleep cycle for my oncoming night shift but really, I have always wanted to catch the Atlantic Ocean before nightfall.

And I am not disappointed.

Rest.

At Rams Tor I decide to lean into the sea.

I have decided to take it.

Rest.

Take all of it.

Rest.

I have decided to take the whole Atlantic Ocean as my slumber.

I want to be tucked in.

Rest.

It's 11:30 when I have finally driven home back to Cardiff.

My family finds me at the kitchen fridge. I’ve helped myself to fridge cold sweet, sweet Splott Market plums. Their purple skin burgeoning open with juice at my lips.

They ask me: Have you rested?

Has the whole ocean rested You?

ACT 4 – Day 1

15:15

My arms are heavy and overflowing with pebble dashed Ishihara plates, a 3-metre Snellen chart, a rebound tonometer and a portable slit lamp. An indirect ophthalmoscope sits in the crook of my arm and there are dilating drops, an occluder, pen and paper with the name of the bed-bound inpatient I need to see overflowing out of my scrubs’ pockets.

I have practiced the order of examinations and investigations I will need to do, repeatedly in my brain while I rummaged around the outpatient department scavenging my tools. My mind also carries the number of letters that will need to be dictated on my return and the burgeoning number of patients waiting is forever the summit on the horizon. But this is important.

It’s a simple question I’ve been asked to answer: how much can this person see?

Breaking down the subsequent parts that make up our vision is epitomised by the precarious balance of equipment currently in my arms. The diagnoses trickling into a fjord in my brain.

Must check this. Must document that.

I set my sails, stabilise my raft and as I reach for my oar and swing open the outpatient eye department’s door to set off.

I stop.

In front of me there is a large canvas, taking up two-thirds of the height of the wall. It’s titled “The Beach”. An abstract layering of yellow and gold sand leading to a patchwork stitch of blue sea. The stretched canvas shows through the fat bubbles of acrylic paint overlapping to make the sand come alive. I can almost see the crunch of crisp sand and how it turns matted before becoming ocean.

The blue paint has been brought into stark lines with white tipped ridges. You can feel that vacuum of space before a wave is to crash.

The sea spreads into cloud streaked sky. I can feel the heavy end of summer air in a chilly winter hospital corridor.

It hits me, this has always been there.

I have instantly scuttled through my mind’s eye and found it there in the corner of my vision for months.

But this is the first time I have seen it.

ACT 5 – Day 1

18:00

I find myself in an art gallery. A proper one. But I’m still wearing scrubs, my on-call pager is clam-shell quiet and I have a cling film-ed wrapped cheese sandwich and a chocolate bar next to me – still untouched.

I’m in a cuboidal room with deeply coloured rich walls with national and international renowned pieces of art. The lighting is warm. There is no music. There is a sign on the wall inviting me to write haikus inspired by the works and leave them anonymously behind. Dotted around the room there are large square sofas. I’m currently sitting on one of these. I am alone.

Once you start looking for the art in hospitals, you realise that this is not a rare and isolated affair. I have found corridors with prints, clinic rooms with pastels and waited for lifts in watercolour-ed atriums. I map out the long way around to visit my favourite pieces again.

But this is the first time I have seen a full art gallery at work. I am astounded by the luxury of space. It sits just off the main thoroughfare of the hospital like some annexed appendage. And I am grateful.

In front of me there is a large still life of flowers and fruit. I can see each pink rosebud. The vase they sit in is blue and white. I can make out the swell of purple tulips

Hospitals house joy and terror and hope and hopelessness. Art in these spaces can feel burdensome on top of all this. It can feel sickly luxurious and out of place when seen for the first time.

There is a single orange poppy or carnation. It is difficult to decide which one as there is a purposeful lack of definition of its leaves. Instead there is a distinct texture and patina to this bulb.

Hospitals have a gravitas that differs from art presented in other settings. There is a different kind of privilege to this art. The privilege of time. The privilege of space both physically and mentally. The privilege of both physical health and mental health.

It's admitting that at certain times for certain people it is not right for them.

But also, such spaces are essential.

This raises interesting questions.

How do you accommodate and curate for such a space?

Can hospitals be spaces for controversial art?

Should they be?

Should engagement be encouraged, or personal space sanctified?

I think these are difficult questions to answer and maybe the whole point of hospital art is that there should not be any need to have these answered.

A peach and plum sit on the table below. They seem flat as if rolled off the artist’s palette. Walking closer, I can tell there's a yellow after-wash over the whole piece. It reflects back in the light

Art can feel easy sometimes to experience. We are surrounded by it. But there is something in hospitals that makes it feel like a conscious choice. Art will forever be subjective and the experience of engaging with hospital art will be even more intimate.

For me, such spaces have been essential in maintaining the balance I find at work. It has taught me the importance to pause. Take out the conscious time to view. Reset, recharge, restart.

It makes me wonder if all practitioners take as much fascination with their workspaces. I’m drawn by “The Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris” by Gwen John. The stark simplicity of this piece emanates a sense of rich, rich contemplation. I find more to read in this than in a portrait. The piece invites us in to reflect, to see the tender tools of her trade. The soft warm corners and the intimate pause she has presented highlight the humanity in her artistic practice.

A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (1907–9)

Oil on canvas

31.2 × 24.8 cm

Purchased with the assistance of the Derek Williams Trust and the Estate of Mrs J. Green

And I feel this humanity of care invites us to bring similar moments of contemplation into both not only artistic practice but also self-care. Whether that be a chair, desk and a window in Paris or being alone with a cheese sandwich and art at work.

My clam-shelled pager has cried it-self awake.

I’m being called back.

I put the still plastic wrapped sandwich in my bag.

I pocket the chocolate bar for later.

ACT 6 - Day 2

08:45

As I am changing my home clothes into scrubs and prepping my room in this Covid-era, I make sure to open the horizontal slit window that’s high above me behind my chair. It's designed to let in air and light but I find myself craning hopelessly to see out of it. I open it just a crack. Then call my first patient.

11:30

The morning has passed in a flurry of uveitides, counting anterior chamber cells, counselling patients, holding a stare over masked rimmed creases longer because I can’t hold their hand. Telling people when I am not worried. Telling people when I very much am. Telling them with empathy, sympathy that “I am sorry. So deeply sorry” when there is absolutely nothing else we can do.

There has been a far sound.

Small but distinct. The silvered murmuring of sea and sand and the occasional squark of gulls. Oh the constant, rhythmed, resolved, reliant coastline.

Calling as if to say:

I am here.

Things may change.

Change is inevitable.

But I will still be here.