This morning I hear the seagulls from my temporary office in a spare room. In Caernarfon I’m closer to the coast than I ever was growing up. But I still can’t see the sea, it’s hiding behind streets and castle and recycling bins. I’ve always lived close enough to see, smell and walk to the sea than I haven’t, and the seeing is my favourite. To me a ‘coastal community’ is in a way an ‘ordinary community’. But coastal communities aren’t necessarily on the fringes, you know. When thinking of the coast, some people think of a line, a border, and therefore of something far from the centre. But to be on the coast is to be between land and sea, surely? In the centre between two worlds.

There’s a perfectly true story (or at least, it should be) about a farmhand from Uwchmynydd, in the furthest reaches of Penrhyn Llŷn, a place so coastal you can see the sea on either side in some places. He won a ‘Spot the Dog’ competition sometime in the middle of the last century. This competition uses a photo of sheep in a field being herded, but with the sheepdog removed. You have to use your experience of dogs and sheep to find the location of the dog. Anyway, the prize was a trip to London, and there he went for a week, this farmhand who’d never ventured much further than Pwllheli, the nearest town. On his return, somebody asked if he’d enjoyed London? ‘It’s all right,’ he said ‘only it’s far from everywhere’.

The centre of your world is wherever you want it to be, I think. This is clear reading through this issue of Cynfas as these marginal, borderline places between two worlds become central to works I’ve had the pleasure of editing.

I love them. Just as I love the shore, whatever its shape. Just as every shore is similar but not identical, so all these works are all different but with an uniting, underlying current.

A love story, or stories is the catalyst for Lois Elenid’s heartfelt monologue. A relationship between two sailors, and between them and the sea. There is a love of community and a way of life, and an acknowledgement of the struggles of queer life in a rural place. But throughout, the sea is a haven and protector.

Lowri Hedd’s magical work is also a mixture of feelings and viewpoints as she combines sound and improvisational poetry and visuals. The border in question is in one way quite literal, with the Menai and Porthaethwy a central theme as the ‘welcome’ ebbs and flows with the tide.

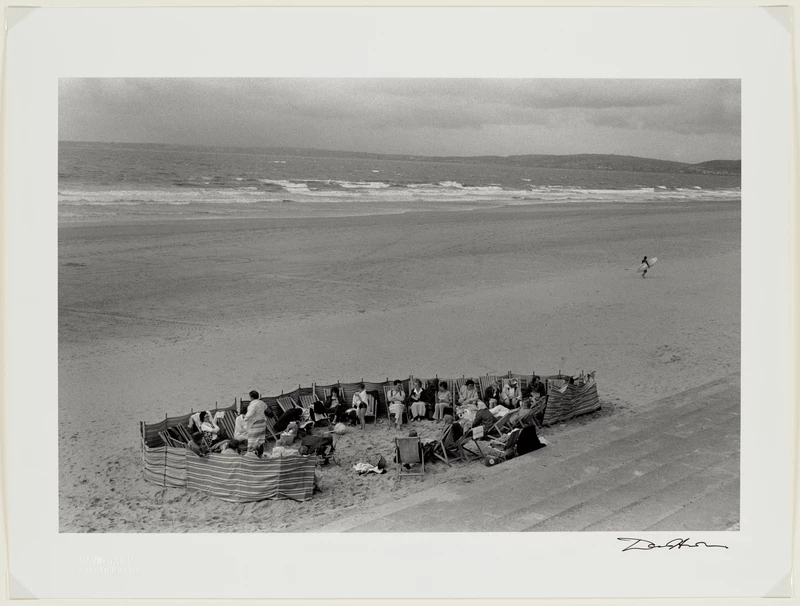

Gwenno Robinson plays on the word llanw (‘tide’) as she discusses something very familiar to me: the seasonal coming and going that is inherent to many coastal communities. We also get a peek at Porth Einon in a series of photographs. She ponders the nature of her home village, and her and her family’s relationship with its seasonal nature, as it varies throughout the year.

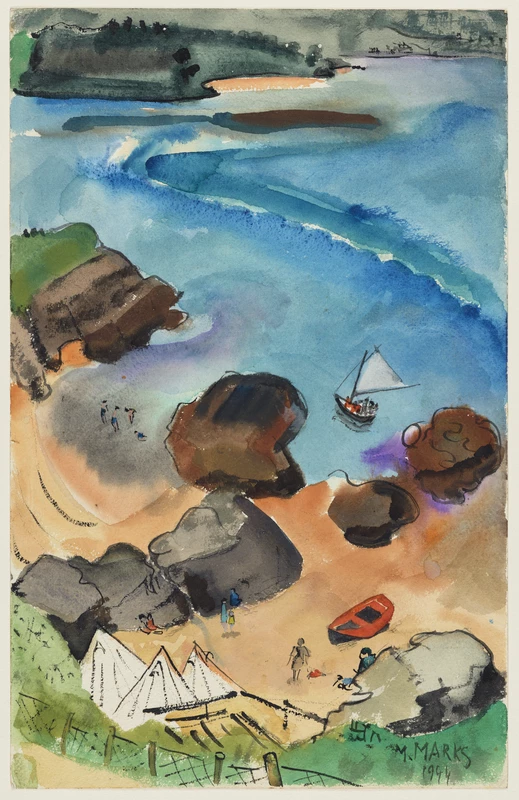

A varied kaleidoscope is also central to Onismo Muhlanga’s dreamlike work as sound, poetry, voice and video combine on a journey through Wales’s coastal communities. He draws on the past as well as the present as tide, foliage and communities combine. I felt a wave of nostalgia as I watched the work the first time, but it also looks to the future.

I hope you enjoy roaming the coastal communities and landscapes in this issue of Cynfas. Communities that are, in essence, ever changing. They are also in many ways bellwethers, caged canaries in Victorian ironwork, Cassandras in sand temples, in all their dogshit and seagull glory. We should remember them – they are after all the places that meet the tide head on and bear its brunt.

Llŷr Titus

Caernarfon 2023