My relationship with food has always been a bit complicated. I had a limited palate when I was younger, and being autistic means that food comes with a number of challenges – the tastes and textures, the processing required in order to create a meal, the inconvenience of having a physical dependency on it, it can all be quite overwhelming. On the other hand, I do love food; I love the reaction that people have when they eat food that sings to them. I love cooking for people and cooking with people, and my love for food is very much rooted in my love for people. Food is most enjoyable when it can be enjoyed with others. If art can be defined as a creative product which excites emotion in its audience then, in my world at least, food is most definitely art.

Aubergine Café is owned and operated by autistics here in Wales. It is a space where art and food come together, founded through my own need for accessible work and social spaces. I have always intended the Café to be a physical and metaphorical space for human connection and creativity. We hire autistic and neurodivergent artists to deliver some truly inspiring arts workshops that never would have seen the light of day had an opportunity with an autistic-run organisation not arisen. We are discovering untapped sources of creativity. We make decisions collectively with members of our staff and community, sometimes over food. This relationship with the community allows them to see themselves reflected in role models, and find the confidence to make a submission or try something new. Not only that, but they bring new audiences with them.

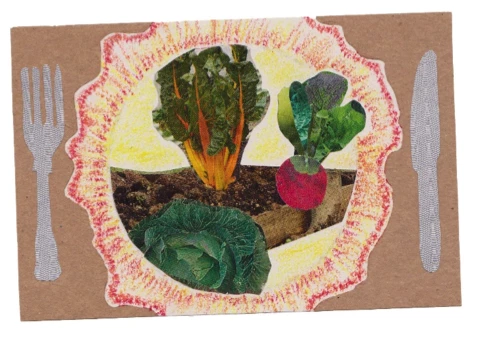

At Aubergine our food is plant-based, and locally sourced if possible, since we wish to contribute as little as possible to the current climate crisis, as well as agricultural human rights injustices around the world. In the wake of Covid-19 and Brexit, food access is a growing concern here in Wales as trading relations become more complicated and climate change threatens global food security.

Historically, whenever there is a great upheaval, a war or economic collapse for example, there are two industries that always do better than others: food and entertainment (or in other words, art). These are the things history tells us are deeply vital human needs.

In this edition, I wanted to see visions of how we might learn from established ideas of the past and reimagine the future of Wales whilst we have the chance to take stock and reassess. It was my strict instruction to step away from what they might expect that a museum would be looking for and to have some fun. I hope that you might find yourself inspired to take part in our postcard activity.

What Wales Looks Like

I remember my first time seeing and really noticing the European mountain ash, also known as rowan, on a field trip to the Rhondda for my Ecology studies with a Cardiff University lecturer. With leaves similar to a true ash, it could easily be misidentified by a novice when not bearing flowers or fruit. The rowan is, in fact, related to the rose, but these shrub-like trees are much more than ornamental, as they provide native birds with winter food necessary for their survival. Traditionally, the fruit is also used to make jam. In this edition, we imagine a sustainable future in Wales with this wonderful, life-giving fruit tree. I relate the rowan tree to the moment I knew it was the right decision to upend and move to such a beautiful country. The grass is literally greener here! In seeing the contrast of the tiny miners’ cottages of Rhondda Cynon Taf compared with the grand Victorian townhouses-turned-flats of the cities, it's strikingly apparent that what Wales looks like – when you look outside your window, the headlines in the local paper, the olfactory journey down your local high street – is different today than it was yesteryear. What Wales looks like to you is a little different to what it looks like to me, in what I see, smell, feel and hear. But it is all Wales. Our experiences TOGETHER is what make up Wales, the life and history of Wales.

Unknown photographer, Missions To Seamen Centre, Cardiff Docks, 1969. © Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Before I came to Wales I was an undiagnosed autistic, making mistakes, not really knowing who I was or how to make a difference, which I desperately wanted to do. I tried various things out to try and find my place in the world: I ran a theatre company, was a computer engineer, a sexual health and drugs worker and even a lap dancer for several weekends. There was a stagnancy about England, certainly in my home town of Coventry, which left me feeling that there was nowhere to progress to. In my adolescent attempt to tick ‘adulthood achieved’ off my list, I married a Kurdish refugee named Erkan. I often jested that ‘It was a Hollywood marriage’, since it lasted a year and a half; the average for marriages of the stars. Choosing to marry Erkan was not my best decision-making for a myriad reasons, but I did have access to unlimited houmous, with a side of anti-government protest, having inadvertently found myself sat in on PKK meetings whilst wolfing down a toasted pita and sipping Turk çay from a tiny glass, in the staff room at Erkan’s Uncle-abi’s kebab shop.

The PKK, the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, is a human rights movement, or a terrorist organisation, depending upon who you speak with. It stands up to injustices, violence and genocide against Kurdish people. I'm told the party sprung from leftist, anti-capitalist politics in late-seventies Turkey, back when Kurdish language, dress and music was outlawed in an apparent attempt to rid the Kurds of their identity. Even today in Turkey, education is not permitted through the medium of Kurdish.

In Wales, many are still feeling the effects of a similarly brutal attack on Welshness and the Welsh language under the British c. eighteenth–twentieth centuries. I can almost hear readers muttering, “Ah yes, the Welsh Not”. A cruel tool, used to strike children who were overheard speaking Welsh in schools. I realised recently that my introduction to the inner concerns of the PKK in 2003 prepared me for the empathy I would later need to understand the pain behind the fight for keeping Welsh alive. It doesn’t take much imagination to realise that Welshness, like Kurdishness, is fragile because of its inverse proximity to (capitalist) power, and whilst Wales has made relative progress in protecting its identity, our Kurdish siblings are left far behind.

Paul Davies, ‘Welsh Not’ Love Spoon, 1977 (performance at National Eisteddfod, Wrexham, 1977) © The Artist

It is in these moments that we come to realise that we don't have to be ideologically, politically or even physically similar to respect life and support one another’s survival. I want to support the idea of collectivism as a means of survival in uncertain times. To take a step up, whilst we have the time granted to us by this cruel pandemic, and see where community activism takes us. To look at our rich history of social movements in Wales and draw from them.

Anna Thomas, Banner – Lesbians and Gays support the Miners (made for the film Pride in 2014) © Lesbians & Gays Support the Miners / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

The 2014 film Pride is an historical drama depicting the true-life coming together of two unlikely groups to strike against Thatcher’s pit closures. Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), a cohort of lesbians and gay men in London set up to raise funds for British miners, was twinned with a number of Welsh Miners’ Support Groups and travelled to Wales to stand shoulder to shoulder with miners on the picket line. A further ten LGSM groups cropped up around the UK, raising £22,500 during the year-long strike for the miners in 1984–5 (around £70,000 in today’s money). This alliance, though uncomfortable at times as people were faced with working through their biases towards one another, is thought to be a pivotal moment in the LGBT+ movement as attitudes began to change towards the LGBT+ community within workers’ unions. Miners’ unions shouted loudly to repeal Section 28 and drove the Labour Party to commit to LGBT+ rights using their membership votes in block numbers.

Dorothea Heath, Miners’ Strike 1984–5 (Binny Jones, of Blaenau Ffestiniog, collecting food donations for Abernant Colliery NUM Lodge) © The Artist / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

We know that we achieve more social change together, but first we need to reach out and learn one another’s struggles to do so.

The Summer of 2020 saw a coming together of people in huge numbers to recognise the issue of police brutality towards Black people, and systemic racism within the UK and elsewhere. Protests emerged around the world, organised by newly sprouted BLM local groups. It was dubbed a great awakening by some in the media, to which Black people responded, ‘Were you sleeping? This has been happening all along’. Incidentally, I was edged out of one such local BLM group after highlighting some potential issues. It seemed as though the key players in the team had little experience of political activism, and their refusal to hear or engage with the elder members on such matters led to them making a number of preventable and embarrassing mistakes. Two steps forward and one step back. We can avoid having to reinvent the wheel by learning from past social movements and organisations, and help future historians and activists by having photos, meeting minutes, diaries and film archived.

Jonathan Blake, Badge Design – Lesbians and Gays support the Miners, 1985 © Jonathan Blake / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Whenever I think about what I’d like the arts in Wales to look like, it’s impossible for me to imagine that without first and foremost thinking about how one could somehow bypass the kind of colonial legacy culture that would get in the way. As a kinaesthetic learner, I am disconnected with the way in which arts establishments imprison beauty. Our culture is to hoard beauty, put it in boxes, safes, museums, where no touching, smelling, or tasting is allowed. It is reserved for those with the means – power, money, privilege. Simply put, this will never speak to me. For me, this will always seem like a missed opportunity, dictated by stiff collars and scrolls. It seems, to me at least, that we should be mindful of which parts of history we draw our inspiration from.

Jonathan Blake / W. Reeves & Co. Ltd., Badge – Lesbians and Gays support the Miners, 1985 © Jonathan Blake / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Covid-19 has changed everything. Suddenly, the venue is no longer the core we wrapped our art around twelve months ago. The way we consume art is diversified far more widely than it ever could have done whilst tethered to a building. We have an opportunity to reimagine what we want the future of arts in Wales to look like and I think we should take it! I’d like one that feels easily accessible and – well – natural to participate in. I want to see it in the streets. What would art look like “down on the ground” – representative of my culture and life, rather than hidden behind walls in museums? What would a future look like where galleries broke free of the shackles of their bricks and mortar and commissioned more public artwork and projects which elevate neighbourhoods? Honestly, I am still working out what my ‘culture’ is, but I have the strongest image in my mind when I think about how I want it to ‘feel’.

It’s a memory. It’s 4 foot tall speakers in the front garden, wallpapered with chipwood and painted kingfisher blue. It's my brother bringing out the duchy pot of curry mutton, cheaper than goat, and the neighbours drifting on their toes towards the intoxicating, spicy smoke billowing out of a metal drum, jerk chicken thighs spitting fat through the hole in the side. It’s feeling the bass vibrate through your chest as you have a go at DJing, and showing the other kids how to do it too. It’s the blanket from my bed laid out on the grass to sit on, with a bowl of dumplin’, sliced open and buttered, some bun and cheese, cucumber sandwiches, with sarsaparilla to wash it down. It’s red, gold and green. One thing that I have figured out is that my grounding in art is sharing: Sharing time, emotions, food, stories and opportunities. My connection with art is the polar opposite of hoarding.

Vibe

It's the heady waft of Caribbean spice

Rich and warm, caramelised kisses

It's fingers twirling my frizzy brown hair

It's the crash of steel pans

And dancing colours

Red, Gold and Green