When featured on an episode of The Chipstone Foundation’s ‘The Mind of Makers’ in 2013, silversmith Ndidi Ekubia described her work as a synergy of “order and chaos,” the order element stemming from her desire to order the material, and the chaos being a natural consequence. Thus, for art-worshippers like myself, watching her process on YouTube makes for syncretic viewing.

Within seconds, it’s easy to determine that Ekubia’s process is as structured as it is sequential; first beginning with a flat sheet of metal that she hammers into a dish before raising it. Abstract patterns which she has sketched on paper evolve into 3D when she begins patterning the silver to establish form. What started off as an architectural polygonal shape soon morphs into a fluid upright structure that is kept in place by corked linings. As an allegory to life’s contortions, she begins with a machine slate she describes as ‘cold’; it is her reworking of the silver and the spectators’ wonderment that summons warmth into the material.

The punchbowl and ladle (1999) is an emblematic piece, reflective of how life’s forces continually shape us. Its dimpled bowl boasts a 36.9cm depth that is intended to carry a celebratory punch, yet, it has never been used for this purpose. That being said, it is difficult to dissociate its cavernous depth with the eeriness of today’s times. The 2020 outbreak of the COVID 19 virus has meant that there is little to celebrate; whilst panic buying grips black communities in the UK and USA, famines in the DRC and South Sudan break free to reflect each demographic’s contentious relationship with food. Whilst the former grapple with the fear of food shortage, the latter concede with its reality on the other side of the Atlantic.

Even still, the plurality of how Ekubia’s works can be interpreted to borrow from her identity. A hybrid of Nigerian roots and Mancunian watering, it’s impossible to ignore how Ekubia’s background influences her craft as a silversmith. When watching a YouTube video of her work, I analyse her entrancement with her own hammering, the musicality of which she describes as a ‘meditation’. In an ode to fluidity, she disrupts the linearity of all that we know by staggering the ladle like a ladder. By the time Ekubia’s craftsmanship is complete, the silver speaks a new musical language of light.

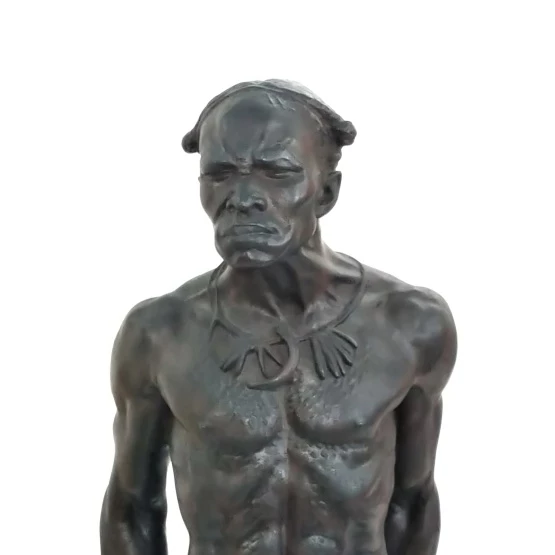

Post-medieval silver finger ring, 2006.7H

The context of silver itself however carries its own complicated dialect. Most typically, in a west African context, the sacredness of similar materials like gold and diamonds draw on historical conflicts like blood diamonds in Sierra Leone and the war over the Golden Stool in Ghana. Most recently, news reports about the looting of Benin Bronzes have further politicised themes regarding material and ownership in regards to works produced by African artists. Still, Ekubia indemnifies herself of this complex by speaking through it; in her own words, she has described that the hand-raising technique she employs derives from her Nigerian heritage. Whilst watching her work, it’s hard to ignore also how her use of her entire body to impress upon the sheet of metal is not too dissimilar to a rhythmic dance.

Nonetheless, in a European context, silversmithing remains a luxurious symbol of wealth. As seen in the popularity of hand jewellery: from medieval gold finger rings and silver gilt rings to contemporary engagement and wedding bands of the present, silver jewellery has and likely always will remain a timeless illustration of wealth, yet it too carries the impunity of imperialism near the palm of its wearer’s hand. As research shows, links between the increasing availability of both silver and punch in Europe are connected to the transatlantic slave trade, thus, Ekubia’s intention for the silver punchbowl and ladle grow ever more convoluted. Therein, beyond the complexity of Ekubia’s identity lies the plurality of how the punchbowl and ladle can be interpreted by its audience. Designed in 1999 for commission purposes, the punchbowl and ladle tests the qualification criteria for what defines Applied Art.

When asked if functionality is a prerequisite for works to be defined as Applied Art, museum curator Andrew Renton, Head of Applied Art, Amgueddfa Cymru, expressed these sentiments: “The category of applied art is fiercely debated in many ways – it is often used to lump together objects made from certain materials, such as clay or silver or glass or wood, rather than thinking about the character of the objects (e.g. why should a figure made of clay or silver be put in a different, lower-status, category than similar things made of marble or bronze?)… My own view is that applied artworks do not have to be functional; I also believe that categorising artworks into ‘applied art’, ‘fine art’, ‘craft’, etc, is a rather subjective exercise and that an object should be judged on its own merits and according to the needs of the artist, viewer or user.”

Most categories and classifications as we know them today are heavily regulated by the prejudice (namely class, race and gender) that is sewn into the fabric of our society. As a result, classifying Ekubia’s work as purely functional or only under the umbrella of Applied Art or even African or British art feels superficial. However, for the sake of commentary, it is important to consider Ekubia’s works in light of the market in which she operates in. Arguably, a threat that the Applied artist, in particular, faces not just as a result of coronavirus but increasing technological output across all industries is the digitisation and subsequent devaluation of their work. With many museums being closed or going virtual as a result of lockdown, works like the punchbowl and ladle cannot be regarded in their intended 3D format. For a silversmith such as Ekubia, whose work relies on tactility, touch and physical display, a key element of the viewing experience is lost in this evolving market. Adding to this, just like any other industry, Applied Arts face competition from other fields such as fine arts or craft which in turn, bear financial and commercial implications for both artists and museums alike when determining returns on investment when commissioning. The general lack of black women being represented in British art as a whole means a portion of the population’s creative expression is not being platformed to the mainstream. Thus, artists like Ekubia face threats on multiple fronts.

Notwithstanding, the same threats that underpin the viability of the art industry for female artists of African descent perhaps may also interconnect them. After all, in times of political cataclysm, many of us look to arts and culture for authority. And, as African-American singer, songwriter, activist and pianist Nina Simone once said: “An artist's duty, as far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times.” Thus, it is vital that in times of national upheaval, the international black diaspora maintain cross-cultural communication across different countries and continents in whatever medium possible. Despite the many otherworldly changes occurring in the world, what remains is the pecking order of racial oppression that persists for black people globally.

In some way, Ekubia’s punchbowl personifies the politics of black lives in this ever-changing climate. The tactile texture of her works consistently represent movement; a word that has been paired with black civil unrest from as early as the 1800s when abolitionists began resisting the anti-slavery movement to the present-day protests of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. Even a global pandemic, which was posed to stop the world’s pacemaker, did not stop the beating heart of the black diaspora resisting the global trauma they’ve experienced. The unfortunate universality of black people’s position as underclass citizens continues to underpin world order; and so forth, an imbalance of power buoys the breadth of the black diaspora.

Medieval gold finger ring, 98.10H

In extension, the showcase of Ekubia’s works in the National Museum of Wales in particular is uncanny. Despite how significant a source Wales is in its availability of silver (as a by-product of the lead mining industry), its silversmithing industry is not as popular as neighbouring countries like England. Thus, the commissioning of Ekubia’s work is even more impactful for the industry of contemporary silversmiths as a whole. Currently, the punchbowl and ladle is part of a collection of contemporary silver placed on long-term loan at the National Museum of Wales by the P & O Makower Trust which supports early-career silversmiths by commissioning work. The trust’s search for a new partner to work with in 2007 coincided with the museum’s development of a new collection of contemporary silver, then the collection was started in partnership with the Crafts Council in London.

Similar to the silver and gold rings humans have eternally sported on their fingers, it is possible to place the punchbowl and ladle in the category of everyday items that are so often regarded we forget them. Like ceramic plates that develop to become dirty dishes, we as humans don’t always ascribe artistic value to the functional items that we use daily. The punchbowl and ladle, however, do not fall into this category of everyday use. When considering Ekubia’s intention for this punchbowl, I cower at the wide rim, imagine it filled to the brim with European punch or Nigerian soup; when analysing the ladle, I imagine generous glugs of either aforementioned liquid, warm and viscous, filling cups and small bowls to satiate the person swallowing. Both punchbowl and ladle are allegories of fulfilment.

On the other hand, when I look at the grooved surface of Ekubia’s works, I am reminded of constant change; change that is natural but nonetheless difficult to handle. I imagine Ekubia hammering the metal to rid it of its colonial internalities, like a drum producing sound, her hammer produces its own language. The blowtorch is a final touch, burning any remaining colonial residue away.

In these uncertain times of global disorder, it’s difficult to get a grip. Whilst government orders discourage physical contact, we, the common people, socially distance, carry antibacterial gel and wash our hands metaphorically and physically to rid ourselves of the unseen.

Still, amongst this cacophony, I remain optimistic for the takeaways that Ekubia’s works have impressed upon me. In her combination of silversmithing and Applied Art, I am reminded of the overlooked privilege of food and nourishment as a black woman living in the west. And in my recognition of the history of goldsmiths and silversmiths, I am reminded of the unconscious conflict we carry every day. My hope lies in the tenuous grip I imagine having when given the opportunity to handle her punchbowl in person after the pandemic is over, and finally having something to celebrate.

Korkor Kanor

Twitter: @KorkorKanor

Facebook: Korkor Kanor

LinkedIn: Korkor Kanor