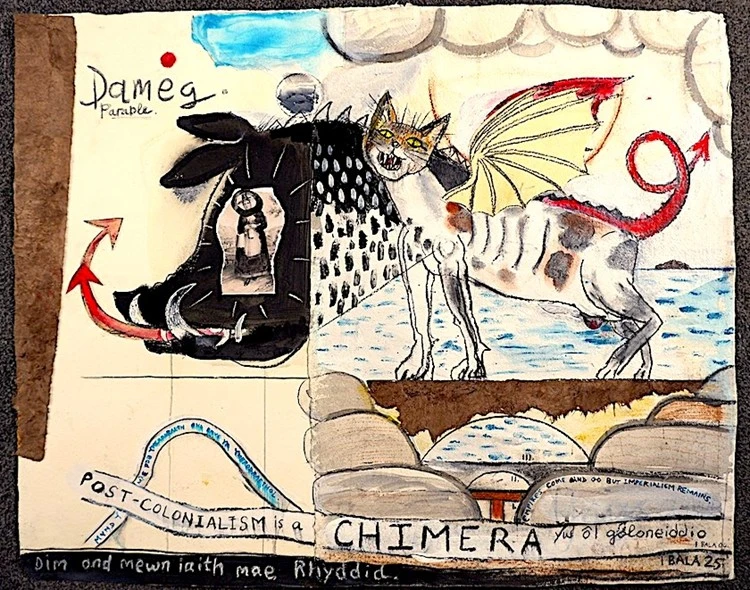

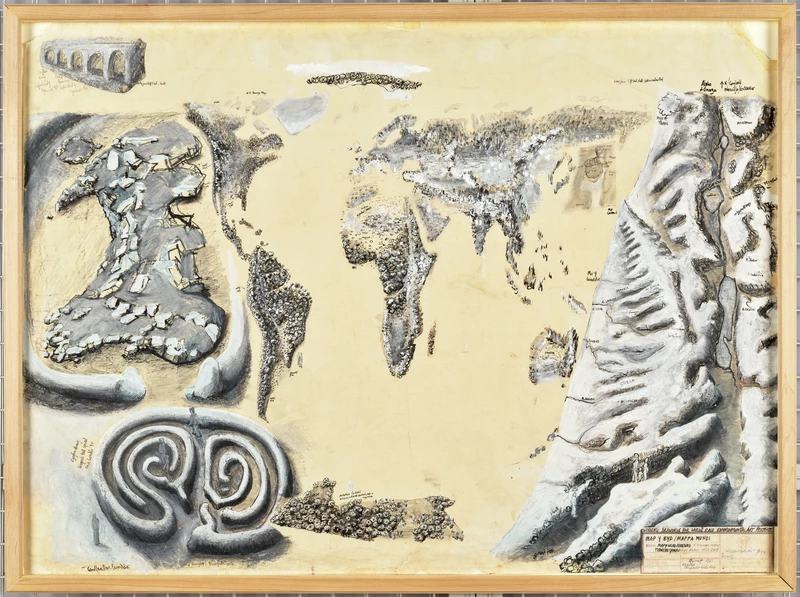

A Zine investigating the effect of plastic pollution in the river Teifi and the Teifi Estuary, Ceredigion, west Wales.

Transcript

Upstream, By Julian McKenny

Plastic Pollution in the Teifi Estuary

We hear much of the worldwide problem of plastics in our oceans, of pacific gyres larger than Wales, in articles revealing the human cost of our exported waste, accompanied by images of beaches knee deep in branded western waste, all at a remove, so conveniently far away …what does it really mean to us?

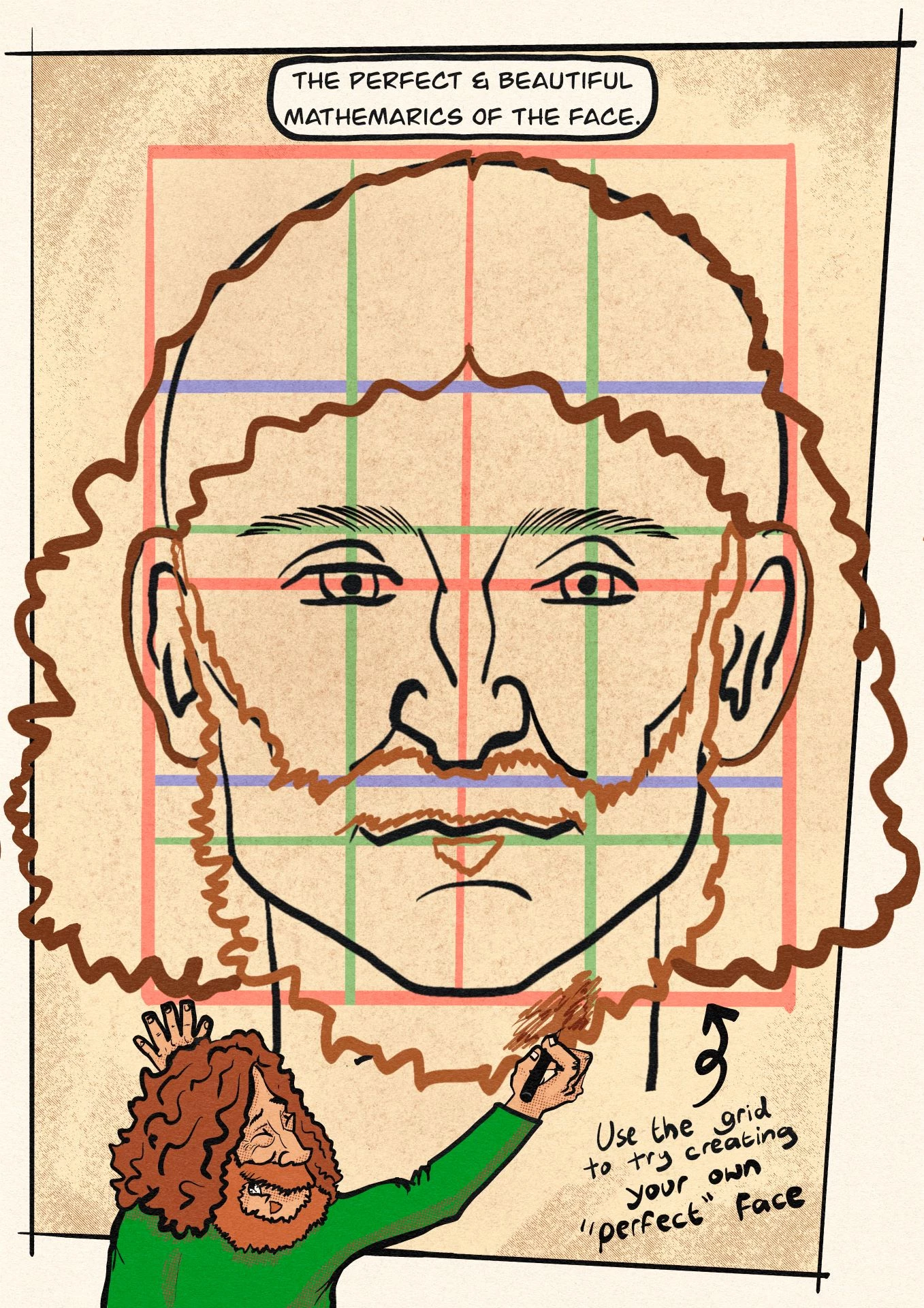

I wanted to see the local impact of plastics - what plastic pollution there is and where it comes from. In the process I spoke to a range of people: dog walkers, holiday makers, litter pickers, fishermen, farmers and marine biologists - had they encountered plastic as a coastal problem?

Reports outline that much of the plastic in the oceans comes from the land, sometimes deliberately but mostly as a result of poor waste management, which is estimated to account for around 82% of the plastic load. From the land this waste enters the rivers, making its way to the estuaries and the sea.

Along Cardigan Bay the Afon Teifi is recorded as being the largest contributor with approx. 1000 kg of plastic per annum. Not surprising when we think of the large settlements along its course – Newcastle Emlyn, Cenarth, Llechryd and Aberteifi/Cardigan itself with St. Dogmaels and Gwbert on the opposite side of the estuary. In second place is Aberystwyth which despite its larger population and two rivers, the Ystwyth and the Rheidol, has less population upstream and comes in at 600 kg per annum.

At Poppit, a sandy expanse at the mouth of the estuary used year round by dog owners, I found surprisingly little plastic. Many of the regular dog Walkers told me that they collected waste as they saw it, feeling a protective connection to the place, keen to keep it pristine. Tourist season saw a rise in litter, including plastic - clearly marked recycling bins are provided and there are litter picking tongs placed near the car park exit.

It is noticeable that the popular cafe uses recyclable materials for its products. There is clearly a local pride in keeping the beach clean and as the tide receded I found only a handful of small pieces of plastic along the whole length. I began to wonder what i might photograph, if indeed there is a problem.

It soon became clear that this first impression did not tell the whole story.

An invisible problem

Now you don’t see it…

I spoke to dedicated litter pickers fi and piers who regularly cycle to the beach from their home in St. Dogmaels to walk the stretch collecting detritus. They see the problem across the year and explained that the beaches are often cleansed by the sea which holds the plastics until conditions arise where one day the tideline will be littered with fragments.

They pointed out that microplastics are the real issue, an invisible enemy that comes from a material that does not bio-degrade but instead breaks into ever smaller versions of itself. A quick online search shows there are groups of community minded beach cleaners like fi and piers operating on most of the beaches in Pembrokeshire and Ceredigion, but there is only so much they can do when searching for something that cannot be seen.

We often have the best of intentions only to undermine them with what we think are the right choices. Dog walkers pointed out to me that these poop bags are a problem in the dunes - the waste, as a natural product, would bio-degrade if not wrapped in plastic.

Most ‘bio-degradable plastics’ only actually degrade when composted in high intensity large scale green waste composting systems such as the ones our councils take the contents of our green bins to.

“It is estimated that 1000 rivers are accountable for nearly 80% of global annual riverine plastic emissions into the ocean, …with small urban rivers among the most polluting.”- UN Environmental Programme (UNEP)

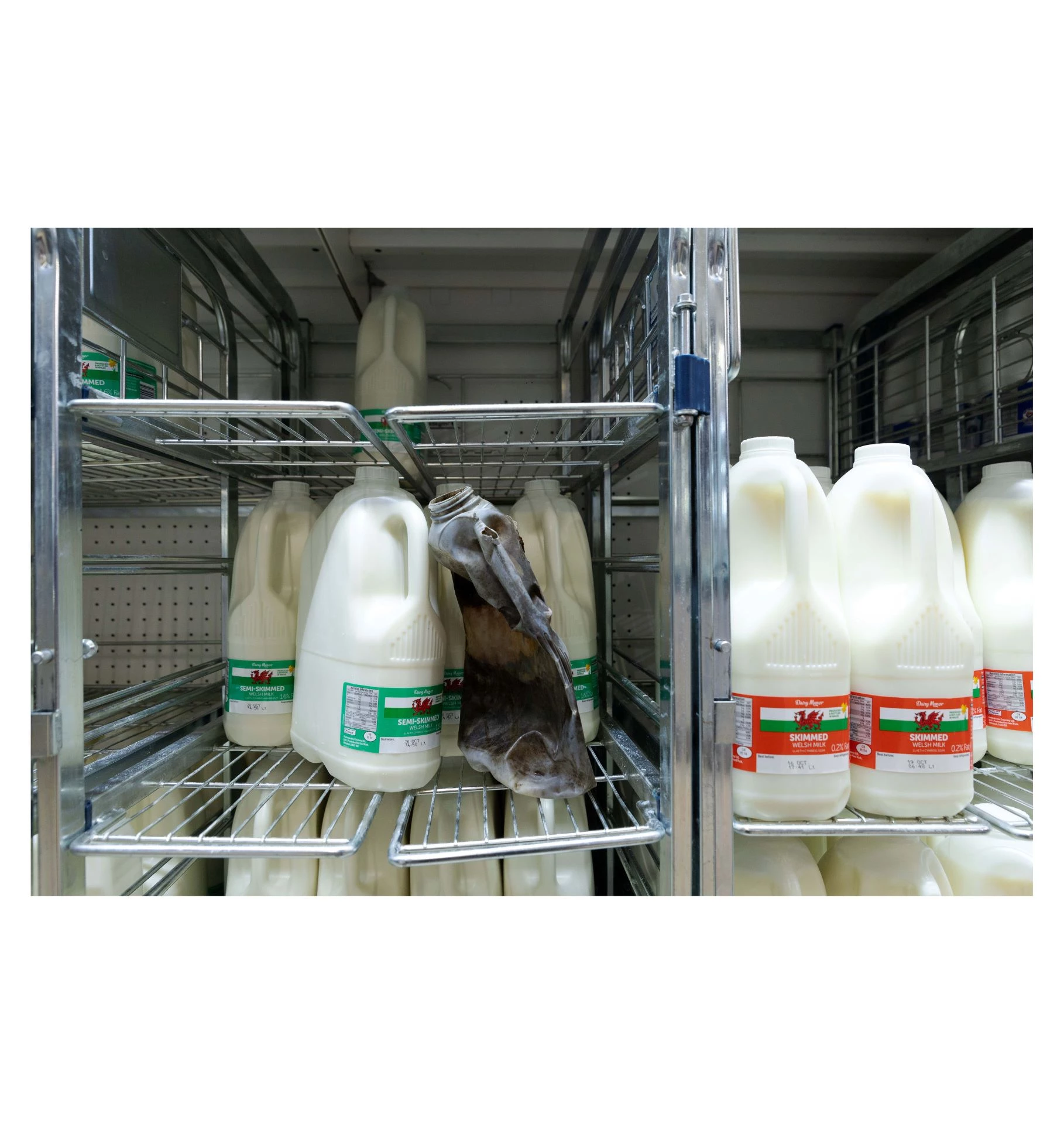

Upstream, high waters following storms and flooding are relatively common. Seen below, at Cenarth, signage is washed away and on the following pages bale wrap is snagged in overhanging tree branches.

Local anglers voiced concern over the amount of bale wrap in the river, especially around the time that young salmon are to be found.

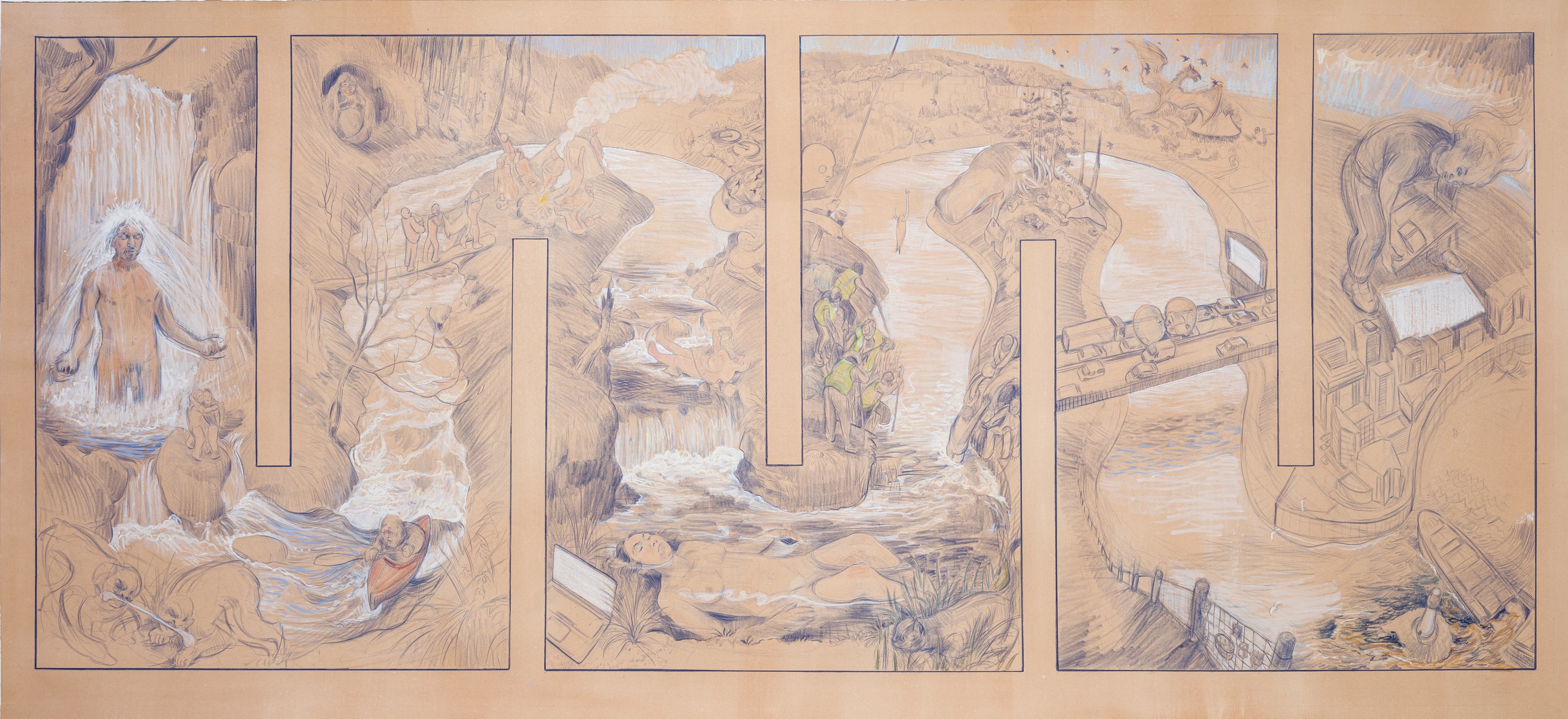

The Journey of a Dinosaur

For a moment imagine that a small plastic dinosaur, accidentally lost, could easily join the river in the floods, jostling downstream to the sea, through the tangling falls at Cenarth, beneath the old and new bridges at cardigan and on into the estuary and the open sea, to arrive on one of the beaches near St. Davids where currents are more likely to deposit their cargo, finally to be found by local beach cleaners.

Did its journey start in the mesozoic as plant material, laid down during the age of dinosaurs, through the jurassic and cretaceous, through heat and pressure and deep geological time, to eventually be transformed from extracted oil to extruded plastic and formed in a Chinese factory into a dinosaur small enough to fit in a child’s pocket, the discardable outcome of a global trade?

“Hector found a small dinosaur - he didn’t put it in the binbag but slipped it into his pocket” the story of a young volunteer ‘cleaning up Caerfai Bay’ from ecodewi.org.uk

I visited Sea Trust Wales at their ocean lab in Goodwick to find out in more detail how plastic is affecting wildlife in the area and spoke to marine biologist Lloyd who runs a recycling scheme in collaboration with local offshore fishermen who bring waste to provided collection bins. A company based in Cornwall called Waterhaul takes this material and from it produces sunglasses and other products, saving over 6 tonnes of plastic so far.

Whilst recycling is a very worthwhile process, especially in nonplastic materials such as cardboard, paper and metals, the reality of recycling plastics generally - of the type we separate into our recycling bins at home - is that only a small amount of it can actually be recycled.

“Britons dispose of nearly 100bn pieces of plastic packaging a year, survey finds.” This guardian article from 2022 went on to comment that only 12% of single use plastic goes to recycling.

Grasping At Straws

300 million tonnes of plastic are manufactured globally each year. Apparently, that is equivalent to the weight of the entire human race.

The 88% that is not recyclable - hard plastics - end up in landfill or sent to industrial incinerators where it is burnt to create energy.

Plastic bags are used for an average of 12 minutes each. A plastic bag can take 1000 years to break down.

Of the categories of plastic only types 1 and 2 are well suited to recycling – pet and hdpe. Hard plastics and laminated plastics range in difficulty. The numbering system is widely considered to be confusing and problematic, encouraging mixing of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ plastic, making it un-recyclable.

Supermarkets have been recently embroiled in controversy as reports reveal much of the plastics returned to them for recycling are either too dirty for the process or are the wrong type of plastic and they are sent to be burnt instead because contaminated material can damage the sorting machinery.

Evidence shows that recycling is largely promoted as a solution by an industry that wishes to create more plastic. In some ways it is an attempt to put the problem on the end user. We arrive at a situation where there is no honesty about recycling and what it can and cannot achieve, which creates suspicions that seem to be grounded when we hear these reports.

It has been found that by doing some recycling we psychologically place ourselves in a position where, having done the ‘right thing’, we feel able to purchase more products packaged in or made of plastic, which is what the industry desires.

In conjunction with the limited amount of plastic that can be considered suitable for recycling this means that plastic is a problem that we cannot recycle our way out of - which is not to say that we should not recycle where we can, but that we should not look at the end user for a solution, rather upstream, with the manufacturers, where the reduction in production needs to take place.

The long-term solution is to produce less plastic overall, the opposite of what is actually happening.

Instead, we tend to focus on single issues, placing our attention on specific items such as drinking straws (it is calculated that a paper straw must be used many, many times to meet the carbon footprint of a single plastic straw – solutions to these problems really are catch 22 situations).

Not making the plastic in the first place sidesteps all of this.

At both Bangor and Aberystwyth universities researchers are trying to find ways of making truly bio-degradable plastics from seaweed, to create systems using wetlands that can filter out microplastics before they reach the sea and to develop products for the marine industry that can replace the nets and bags we so often see snagged on the tideline.

Did you say nurdles?

At Poppit in conversation with beach cleaners Ffi and Piers, they casually mentioned nurdles. I had one of those moments where you wonder if you misheard a word and hold back before asking did you say nurdles?

Nurdles are the outcome of the recycling process, small coloured pellets used as the feed stock for new products. Online videos show buckets of them being poured into hoppers where they are heated and then extruded into new products. They generally arrive on our beaches when shipping containers full are lost overboard - online there are heartbreaking images of beaches knee deep in white nurdles, as if the heaviest of hail storms had taken place, leaving an almost impossible clean up operation of these morsel sized pellets.

Piers points out that nurdles can be used as an indicator of plastic pollution levels - poppit has shown a count of 3 nurdles from a square metre and over 50 on another day. Unless we gather it, the plastic remains and returns.

Marine biologist Lloyd tells me he more often finds black nurdles at Goodwick, which are from water treatment plants where they increase surface area for bacteria to work on and break down our effluent. The Afon Teifi has experienced a lot of problems with sewage release over the last few years, partly due to salt water flooding into the system at higher tides. He says that waste water treatment is a relatively new approach, treatment works struggling to keep up with our requirements for cleaner water (traces of drugs, antibiotics, diseases, etc. Are found in water samples and used to judge levels of infection such as covid.

In the 1970s sewage pollution of rivers and coast was very high – anecdotally it was suggested that the mussels growing to enormous sizes in certain areas at Goodwick should be avoided due to their proximity to nutrient rich sewage outlets…

In Wasteland by Oliver Franklin-Wallis the author describes running his hands through a plastic ‘flake’, a recycling biproduct similar to nurdles. Describing the beauty of its ‘oil on water’ iridescence he notes that most oil deposits were laid down 180 million years ago and then transformed by heat and pressure. From this comes plastic, a product of the oil industry that does not bio-degrade but remains in the environment for lifetimes. He describes it as -

“Matter perhaps as old as the dinosaurs, falling through my fingers like confetti”

“Nurdles: the worst toxic waste you’ve probably never heard of” Guardian article 2021 by Karen McVeigh, quoted in Wasteland

17 million - the number of barrels of oil used to make plastic products in 2006

450 years – how long it can take a plastic bottle to decompose

50 years – time taken for a foamed plastic cup. Styrofoam does not biodegrade

15 million – the number of used plastic-rich garments Ghana imports from the global north each week

16,000 – number of chemicals used in plastic production

Coastal waste bins – clearly marked to help us separate our waste stream. However, the two sides are often mixed and sent to landfill or incinerated due to contamination.

Red, green and blue plastic becomes microplastic much quicker than white, silver or black due to the colouring pigments that are added.

Use of plastic is set to triple by 2060, propelled by the plastics industry. Over the last five years there has been a 60% increase in pledges by these corporations to reduce plastic use. Over the same period plastic in oceans has gone up by 50%.

Dow chemicals are quoted as being very optimistic about market growth over the next few years as demand rises.

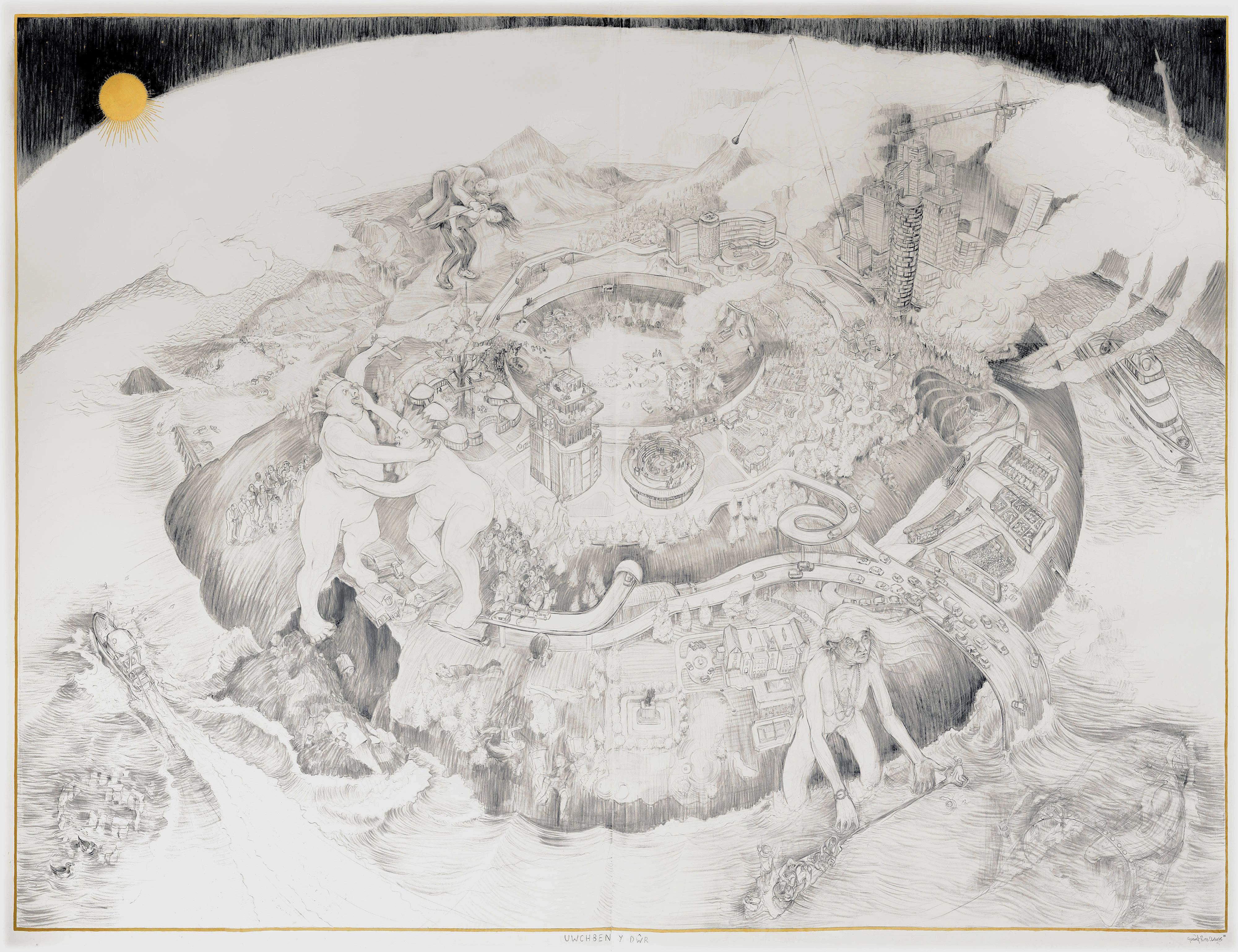

At the tidal mouth of the Teifi estuary is Craig y Gwbert, an iron age promontory hill fort (now an outlying part of the golf course) and alongside it a natural sheltered slipway giving access for an ancient coastal trade. Few hints of occupation remain. One of the markers for the contentious new geological era, the Anthropocene, is our ubiquitous plastic waste, making its way into the geological record for future generations (if there are many …) to contemplate.

In the last few years it has been realised that several of the main sources of microplastics have been overlooked, some of these unconsidered contributors being paint, car tyres and sewage.

Estimates say that up to 40% of paint ends up in the oceans as microplastics.

Most modern paints have plastic polymers in them. This contamination comes from old buildings, renovation, demolition, erosion of paint from surfaces by the weather.

Other ‘modelled’ estimates show that 50% of paint applied to buildings will end up in the wider environment.

Our modern clothes are full of synthetic fibres. Every time we wash that favourite fleece it sheds fibres, microplastics, that enter the waste water stream.

An amount of this is filtered out at the waste treatment plant it goes to. The waste is separated and any pathogens killed, which means the sewage slurry can be used on farmland as fertiliser, a seemingly ideal use for this material.

Unfortunately, the filtered microplastics go with it and from their application on the fields are washed down into the streams, tributaries and rivers that then draw down into the sea, where marine creatures ingest them and, ultimately, we eat those creatures, presumably starting the cycle again.

Where The Rubber Meets The Road

Another overlooked source of microplastics is car tyres, thought to shed ten to sixteen percent over their lifetime.

At Goodwick the marine biologists were finding black plastic bristles on the foreshore and, surprisingly often, pieces of car brake lights.

The bristles were from street sweeping machines and the plastics, along with any unseen microplastics from car tyres, were being washed into the storm drains and directly onto the beach.

Another estimate says that up to 90% of the microplastics in our oceans are from car tyres.

Complexity

Modern life seems so often to be a trade-off between doing the right thing and the wrong thing and how often our best intentions turn into the opposite of that intended.

So as we try to rewind time and ‘clean’ the environment we have so unwittingly damaged what happens when we discover that up to 100 species of marine creatures have formed beneficial attachments with the plastic detritus and that in cleaning it up we will destroy the eco-system they have come to rely on?

Complexity

Plasticide

Recently there have been political moves to bring in a deposit scheme to encourage the return of more and cleaner plastic for recycling, something that has been found effective in Europe.

Corporations have lobbied hard and strongly resisted the move.

Oliver Franklin-Wallis says in wasteland that he realised that the words reduce, reuse, recycle are not just a ‘catchy slogan, but are actually arranged in order of effectiveness’.

Considering that only pet and hdpe plastics can be economically recycled and that they can only be recycled several times before a loss of quality means they end up in landfill or on the beach of a conveniently foreign shore, there seems to be no alternative to weening ourselves off this plastic addiction.

Reduce reuse recycle

In addition to recent news that we are finding microplastics in all our foodstuffs, in our bodies, reducing fertility, potentially causing cancers, making our entire environment toxic whilst remaining mostly invisible, there is further news of ‘forever chemicals’, the result of legacy landfill sites where we thought we had conveniently buried a problem and then turned our backs on it.

Of the 16,000 chemicals used in plastic production, many are untested and unregulated. We purchase our food in these ‘protective’ wrappings, we savour that ‘new car smell’ - the outgassing following manufacture. To me it makes a lot of sense to buy used items and second-hand clothes.

Teifi Estuary at St. Dogmaels

Bisphenol-a (bpa) is a chemical widely used in plastic products that leaches into aquatic environments. It mimics oestrogen (hormones) and affects the sexual development of those creatures.

Researchers are looking to see if it also affects humans once passed through the food chain.

Credits

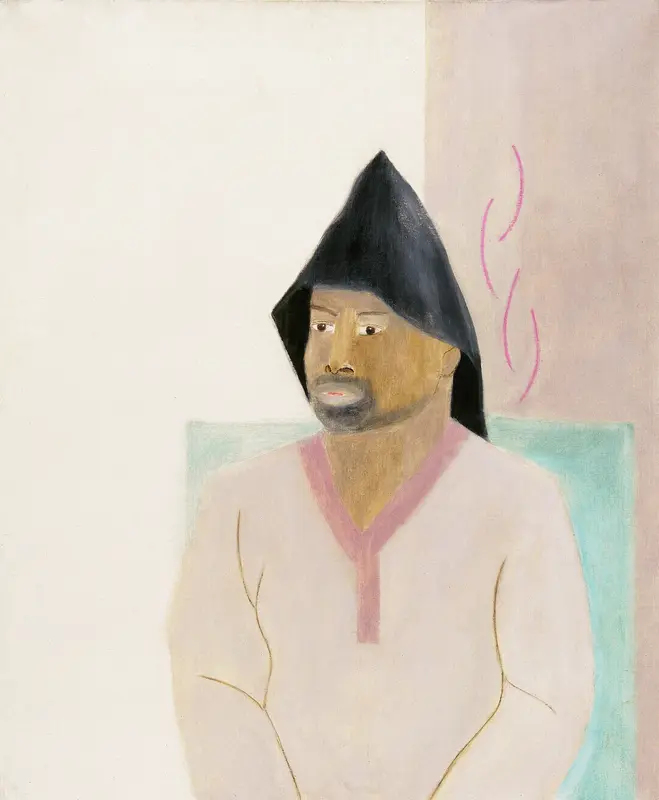

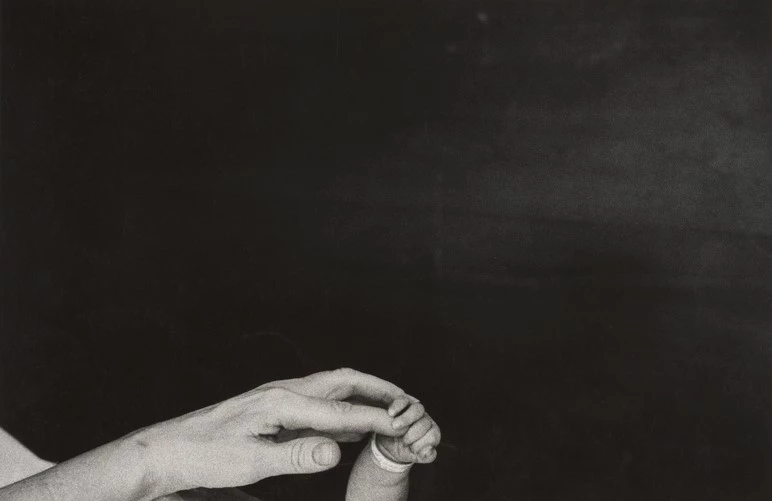

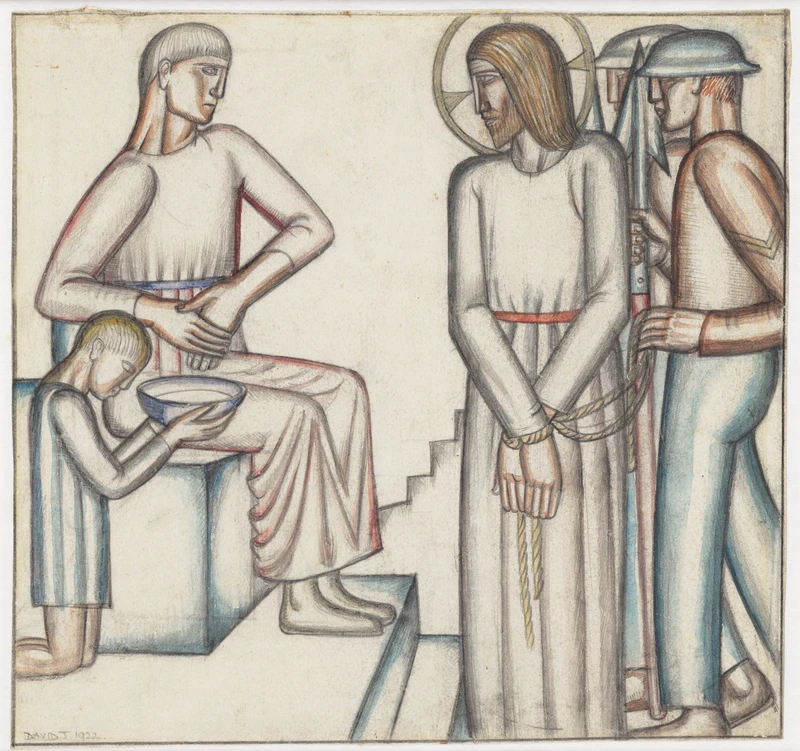

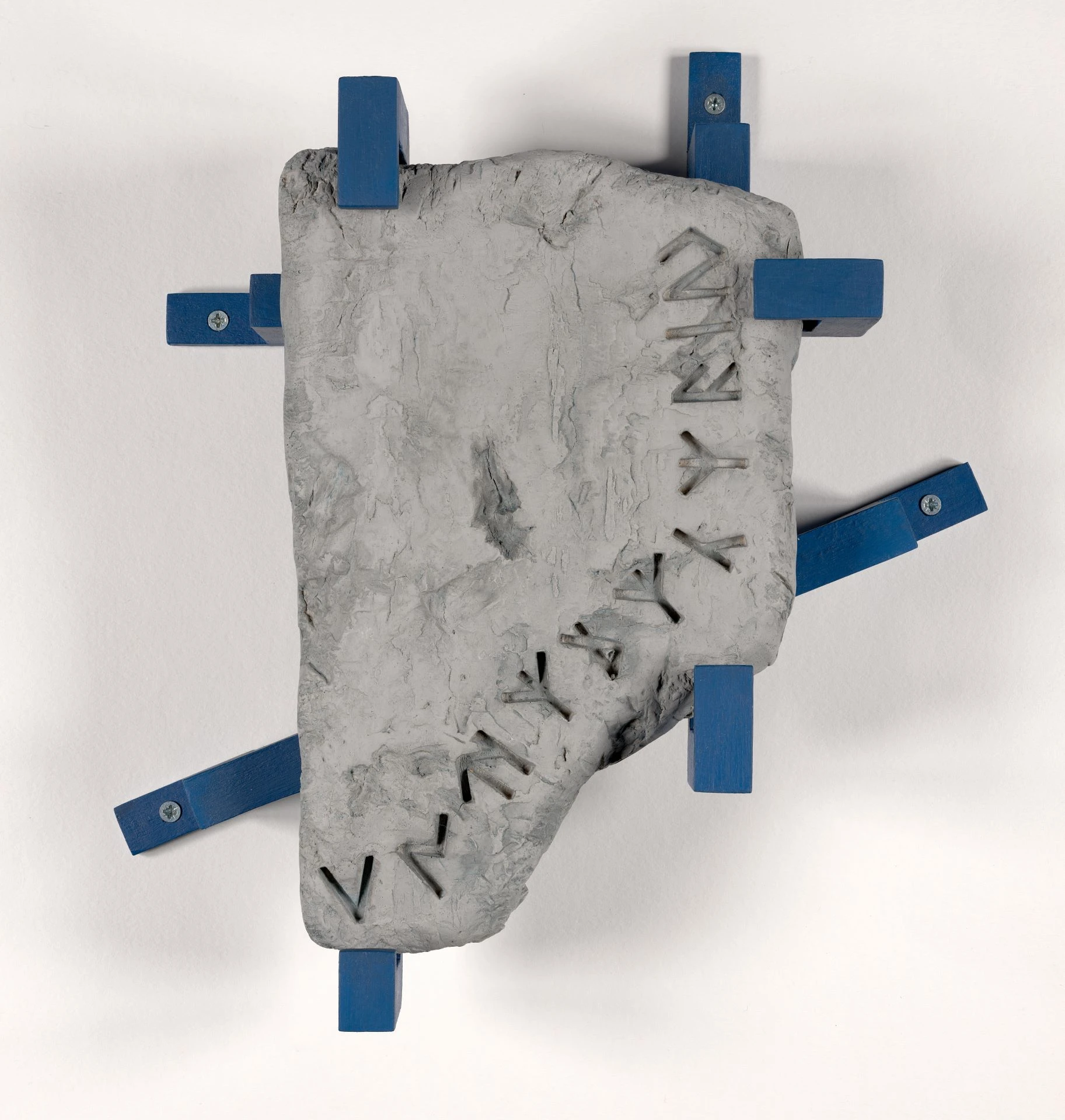

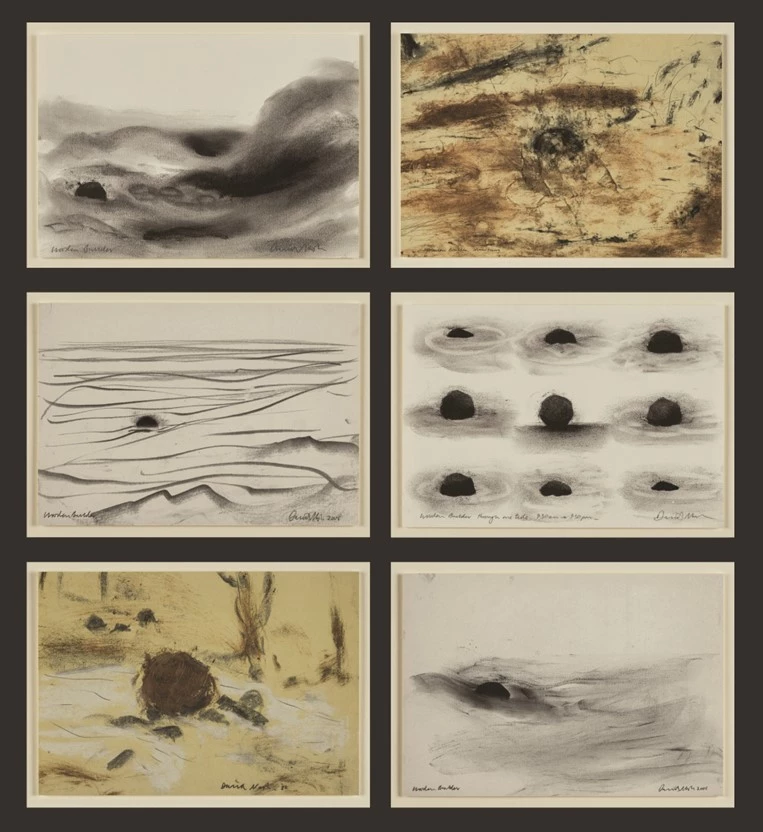

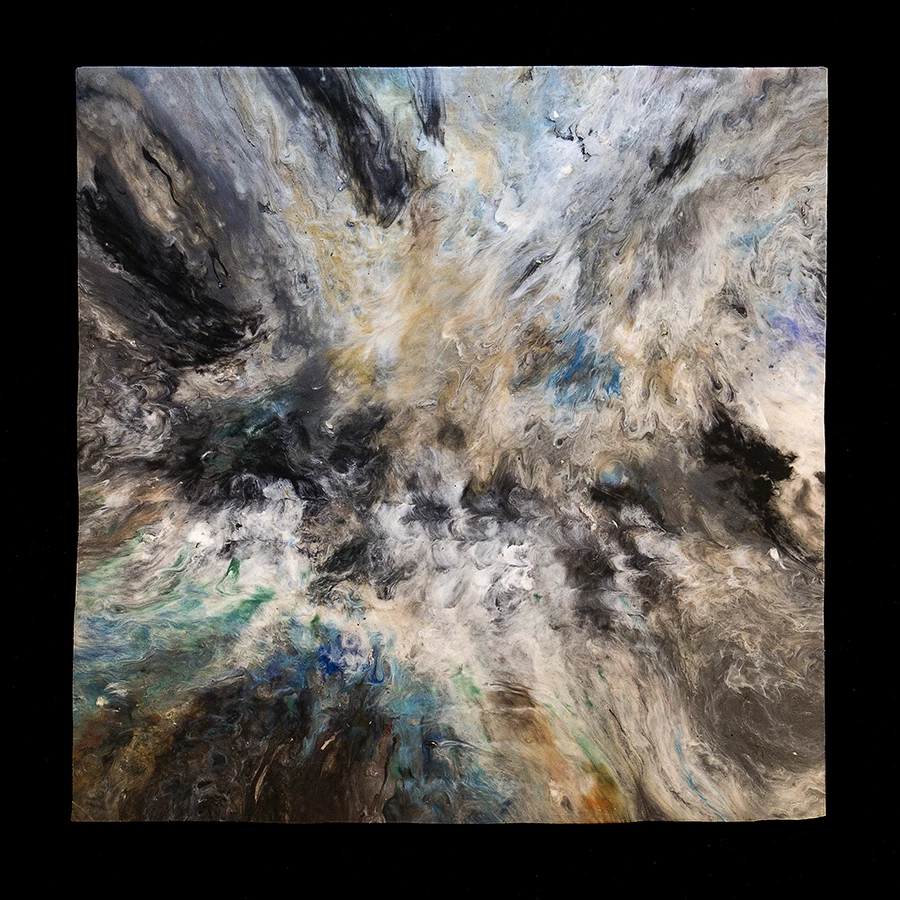

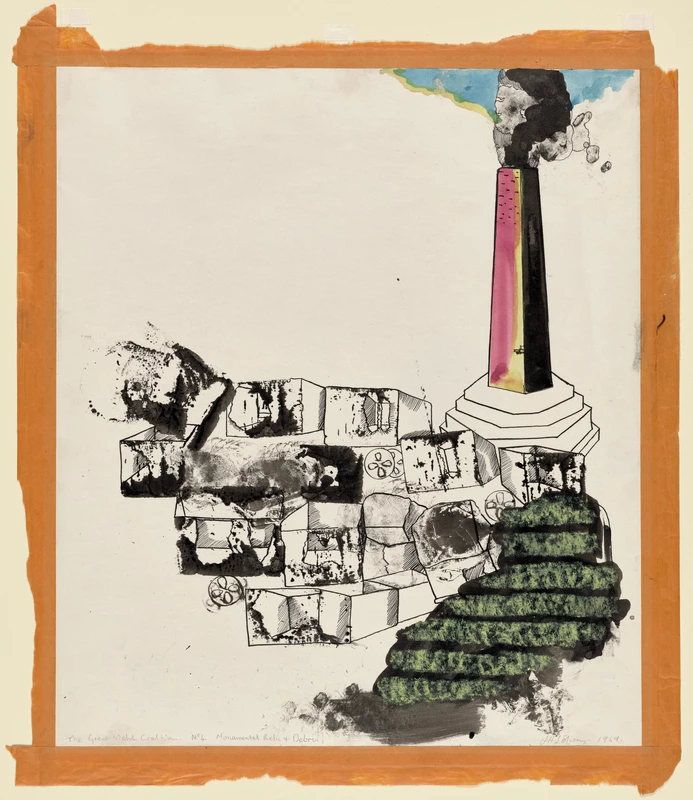

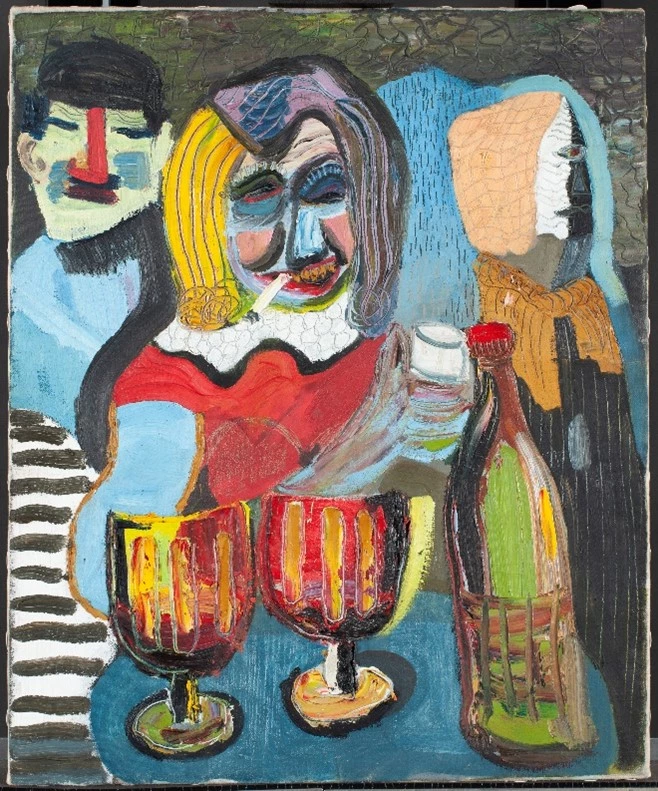

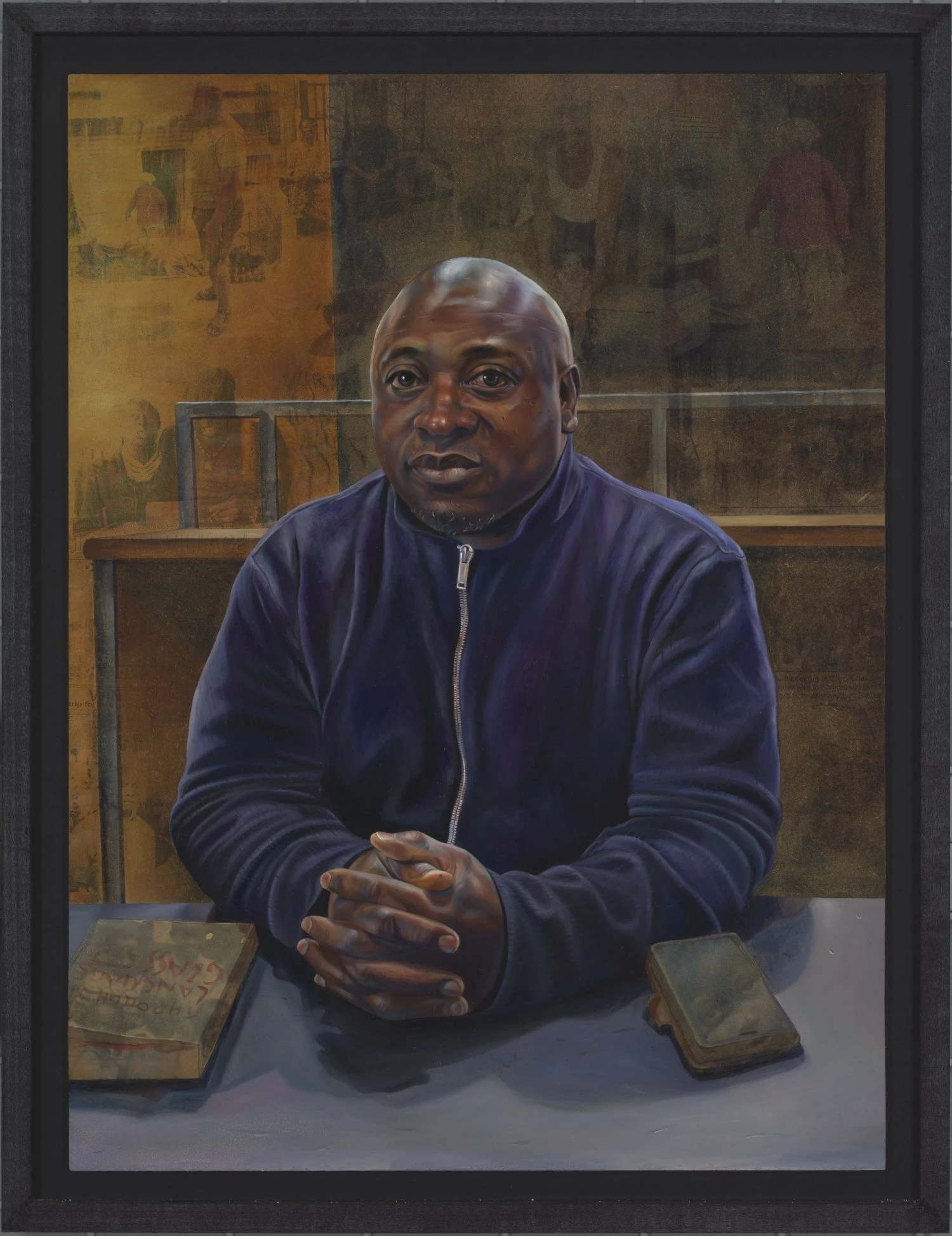

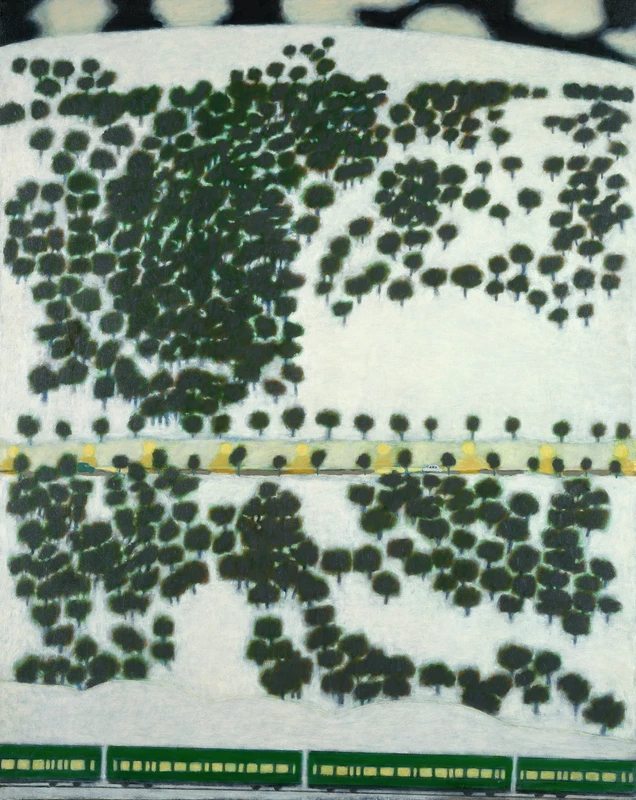

With thanks to CELF who commissioned this work to stimulate discussion around plastics in our oceans in response to the artists Mike Perry (work in Amgueddfa Cymru’s collection) and Tim Pugh (whose work is in the National Library Wales collection).

Also my gratitude to those dog walkers, visitors, locals, business owners and scientists who took time to give their view on a problem that initially seemed invisible - a small amount of research showed the depth and complexity of the problem, tied in as it is with so many other strands of modern life, not least climate change and the fundamental problems of capitalism and global markets.

Whilst statistics and ‘facts’ came from reliable sources and articles they should, of course, be treated with some suspicion and one reason for presenting them here was to encourage a wider discussion and examination of the issues raised by plastic use and the pollution arising from our dependency.

Upstream

An investigation into the effect of plastic pollution in the river Teifi and the Teifi Estuary, Ceredigion, west Wales.

The found plastic pieces throughout were all gathered during the course of the project.

All images copyright Julian McKenny 2024

Julian McKenny is a fine art photographer based near Cardigan, west wales.