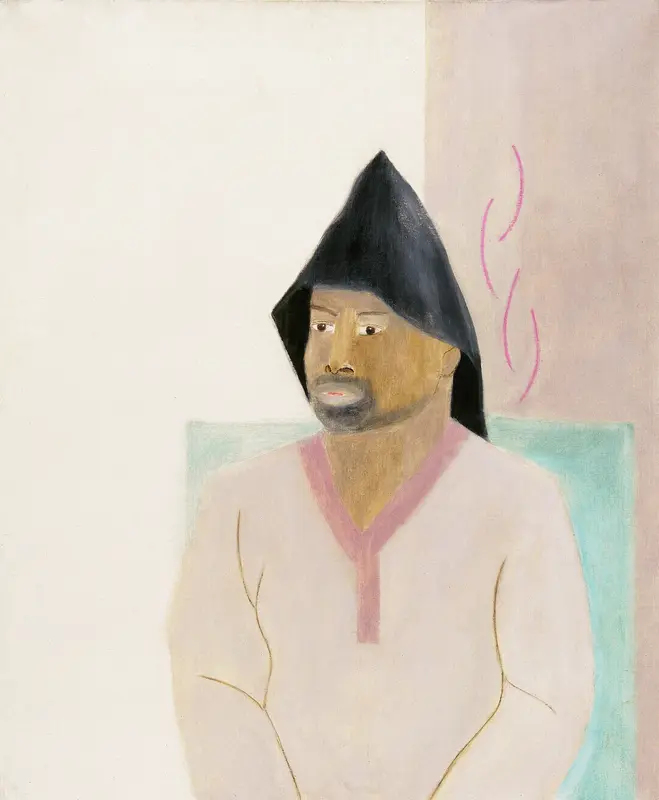

Frank Auerbach: Head of E.O.W

"I have rehearsed every part of the picture until I know it all and then can begin to find some line of feeling that runs through the whole thing. One then paints it all in one breath."1

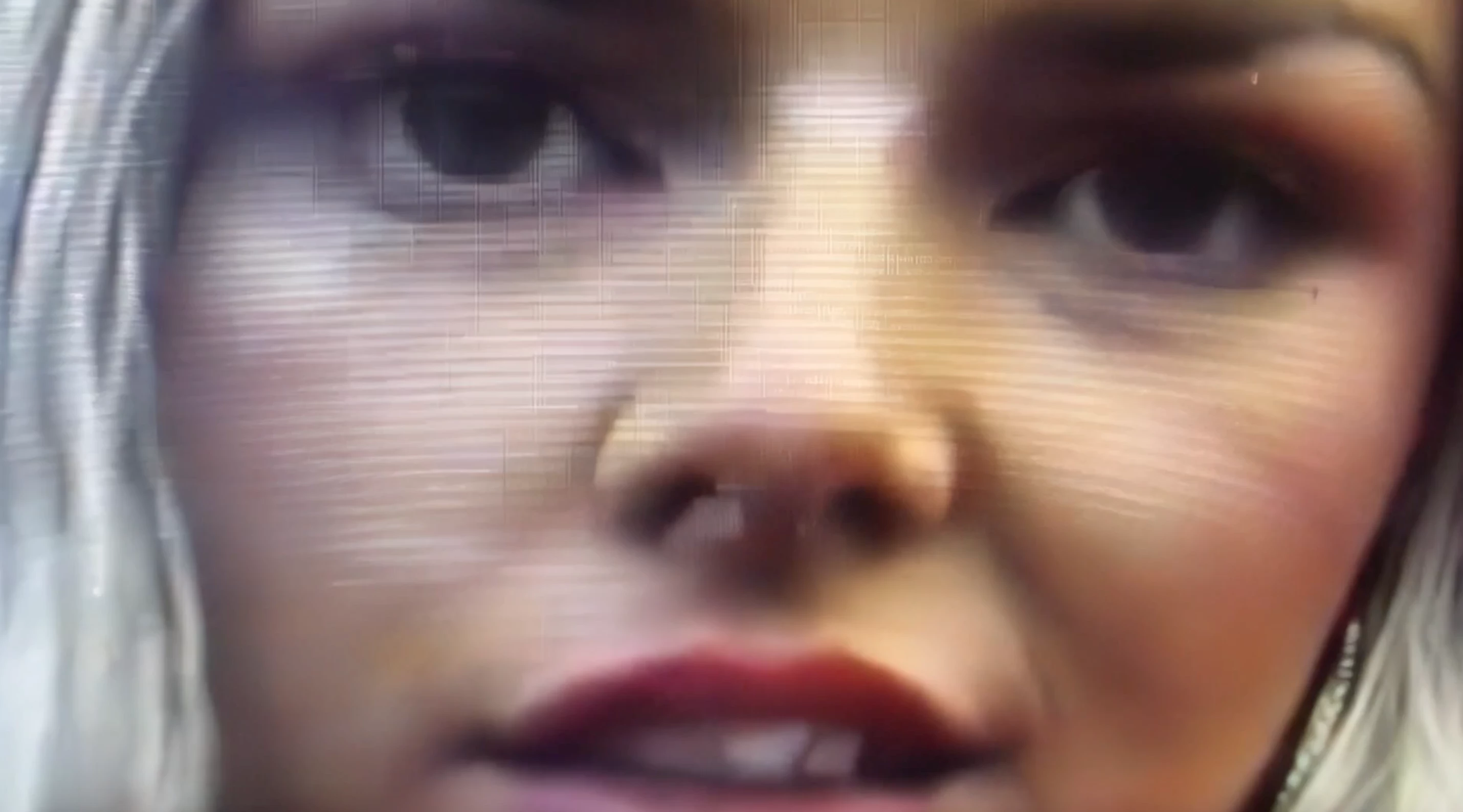

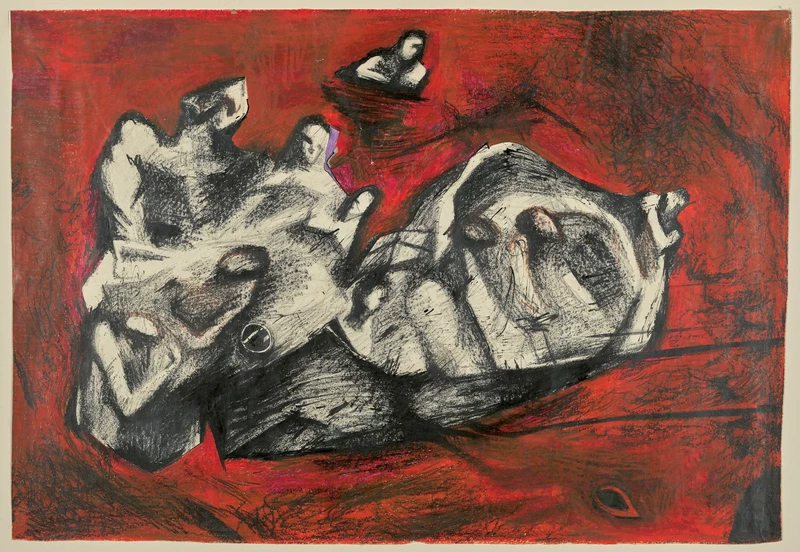

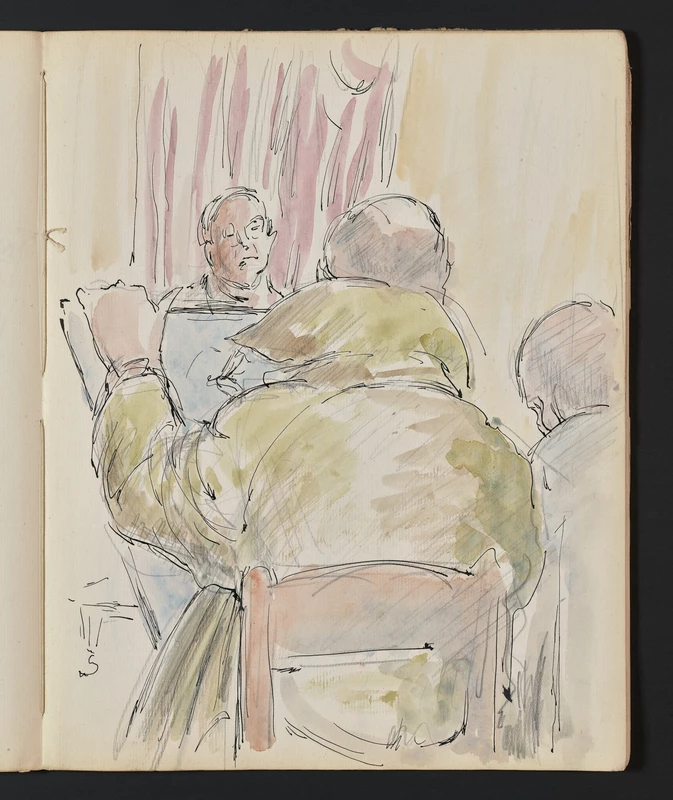

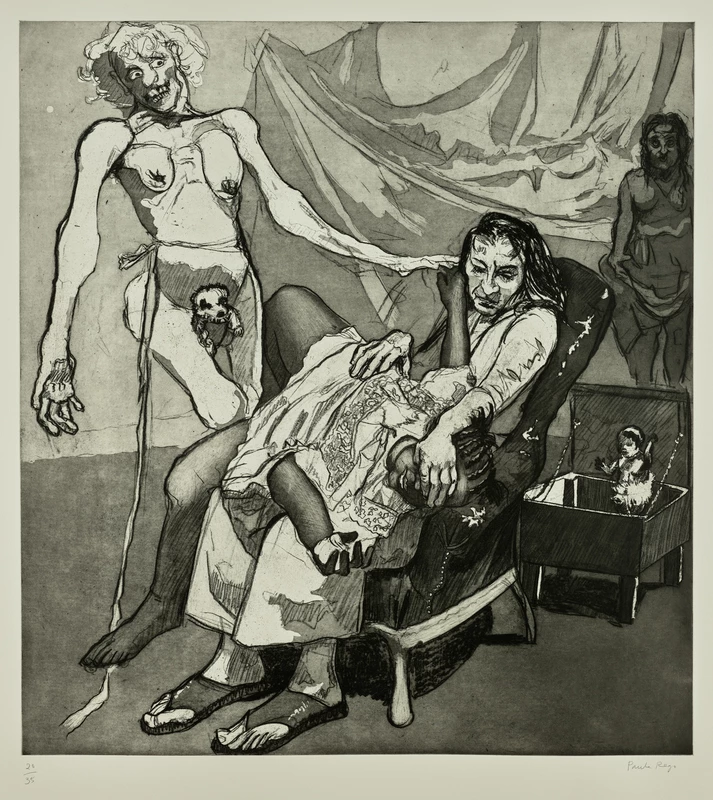

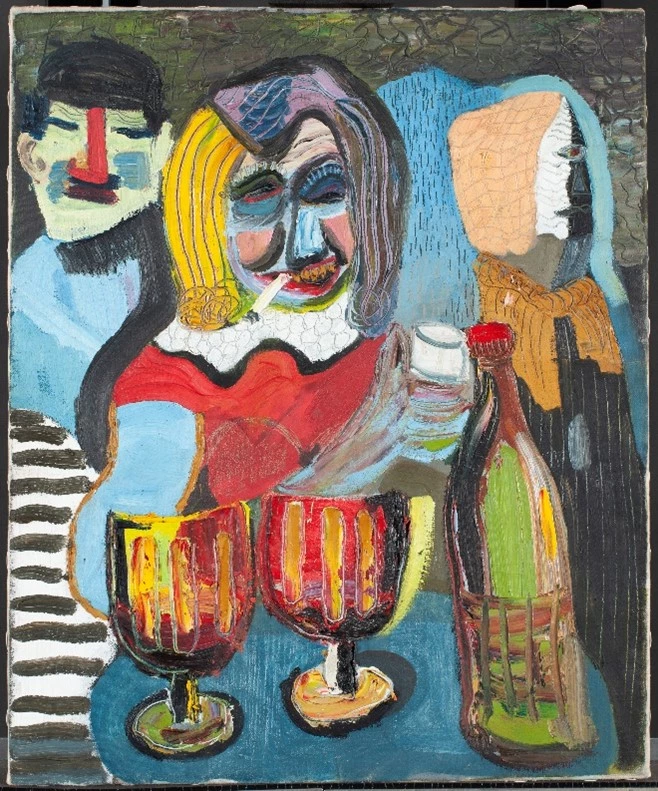

Estella Olive West (1916-2014) first met Frank Auerbach in 1947 because of their mutual interest in amateur stage acting. After the sudden death of her husband in 1947, Stella, a mother of three children, would rent rooms at her home in Earl’s Court as a source of income, where the young Frank Auerbach would become a lodger. Drawn to her striking features, Stella would go on to pose regularly for the artist. The series of paintings and drawings of her similarities reveal Auerbach’s “profound and intimate knowledge of the subject”ii : a prominent forehead and long hair pulled back behind her right ear, her sharp facial features, and a narrow, tight-lipped mouth.

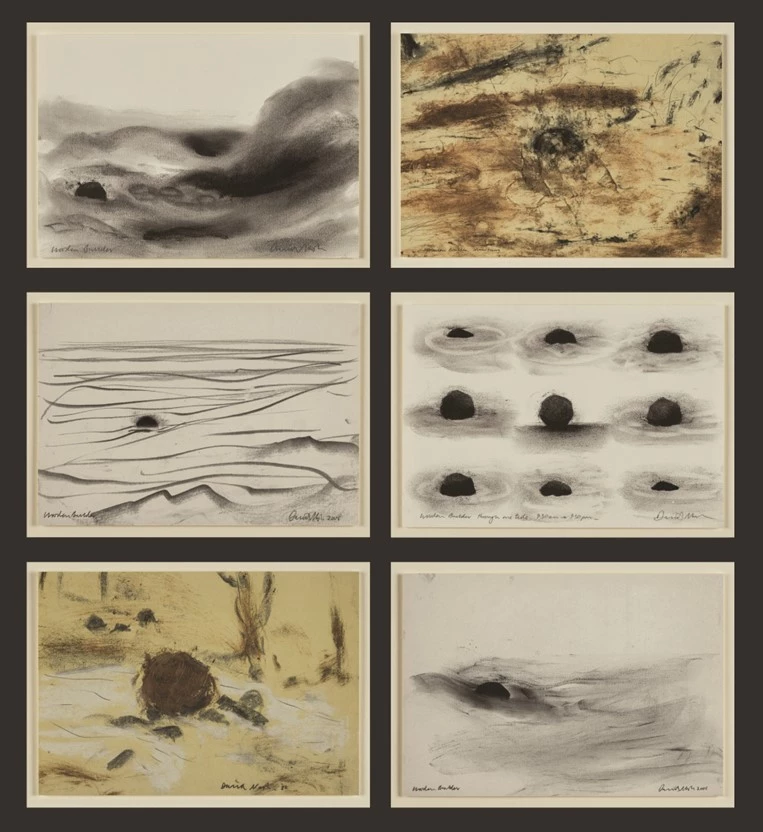

Auerbach’s works of E.O.W. don’t portray specific details; instead, they challenge our understanding of what a portrait can represent or become. This is especially pertinent in our collective reliance on lens-based imagery. Paint or charcoal in Auerbach’s hands is applied quickly, and he often compares each stage of the creative process as a ‘rehearsal’.

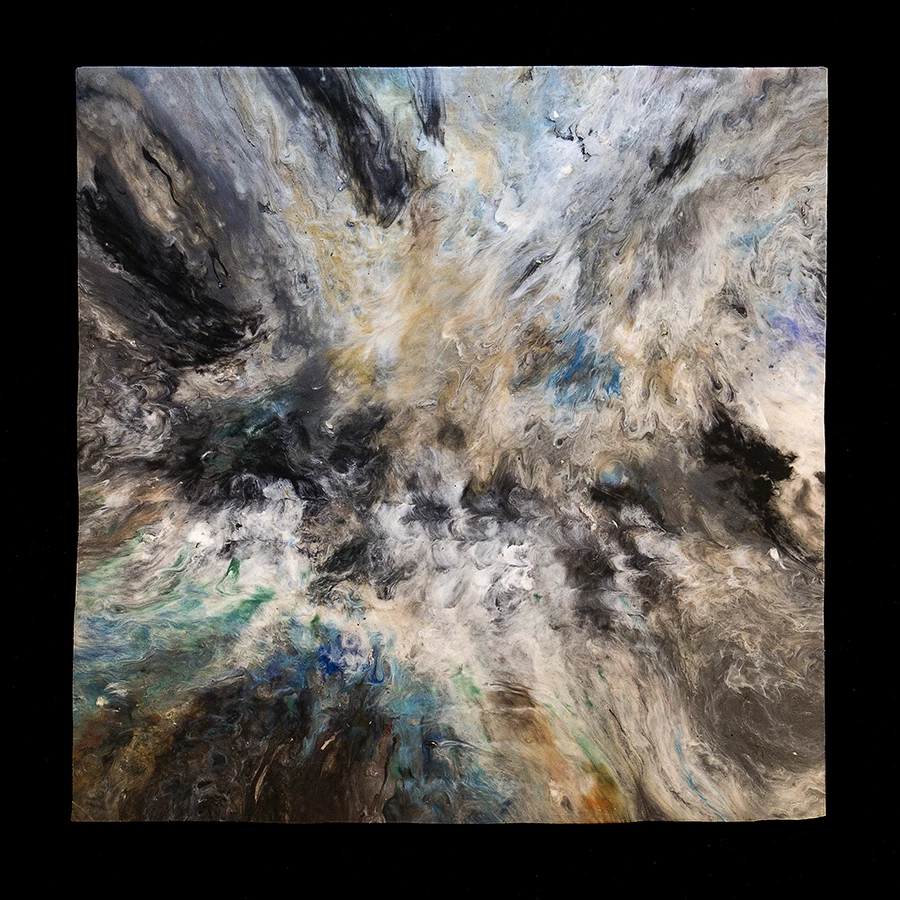

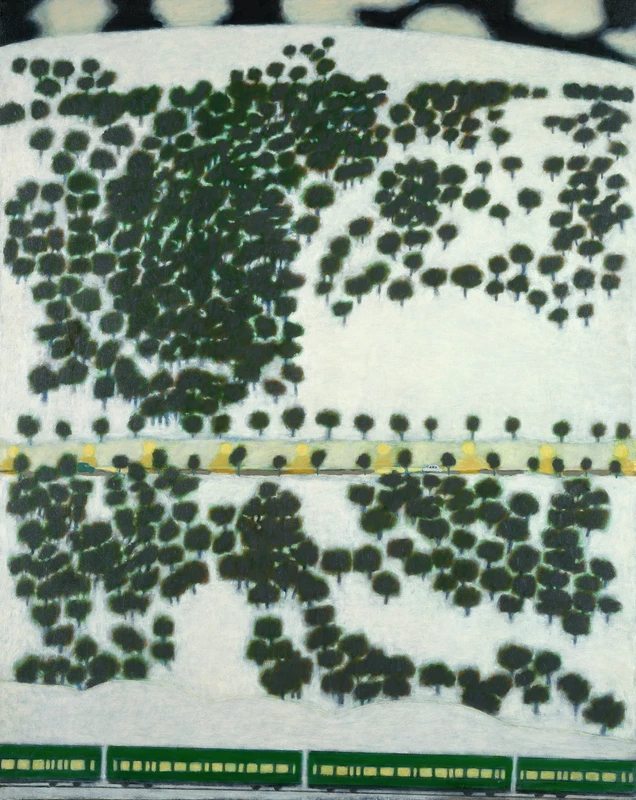

Early on in his career, Auerbach could only afford less expensive paints. These paints came in tones of earth colours which is evident in the palette of the painting. Typically, these colours include yellow ochre, raw umber, and sepia, whilst black is also prevalent in the work. The muted palette gives the Head of E.O.W (1955) an undeniable presence or weight. As Auerbach’s subject matter widened to include urban and park landscapes of London, so his palette range would expand to include bright reds, blues, oranges, and greens.

Auerbach developed a close friendship with the artist Lucian Freud, with both becoming prominent members of the School of London Subsequently, Freud became one of the largest collectors of Auerbach’s works. Whereas Freud typically built up or added layers of paint, Auerbach would (over time) come to scrape away as much paint as he applied. This unusual technique, while leaving traces or a palimpsest of the previous day’s image, clears the surface plane for the next rehearsal. In his own words, Auerbach describes his unique process: ‘Every time I scrape it all off I know a bit more. What was once done with great difficulty becomes second nature, until gradually I have rehearsed every part of the picture until I know it all and then can begin to find some line of feeling that runs through the whole thing. One then paints it all in one breath.’

In the case of the Head of E.O.W (1955), the image emerged after being endlessly reworked alongside an evolving familiarity with his sitter. The result is a painting with significant time embedded in the strata of paint layers. An artwork by Auerbach in this sense is not so much finished as it is paused. In a recent 2024 exhibition, Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads at the Courtauld Gallery, London, Head of E.O.W. (1955) was installed alongside the charcoal and chalk drawing Head of E.O.W. (1956) in the opening gallery of the exhibition, once again underlining the prominent position of Auerbach’s series of her within his body of work.

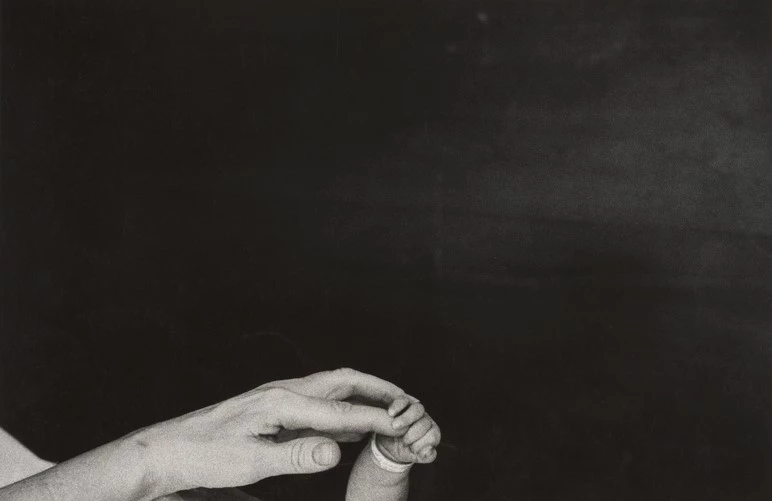

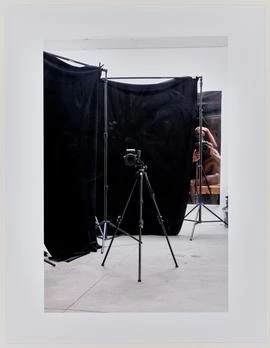

During recent digitisation of the painting, altering typical lighting technique in the photography studio unlocked the sheer scale and complexity of Auerbach’s handling of oil paint. The outstanding combination of image and impasto – the fluidity, drips, paint texture and crusting – combined with the lighting and oblique camera angles bring out exquisite details only visible when up close and personal with the work.

The detailed photographs also show that bright colours exist hidden within the paint mixture, such as streaks or veins of reds and bright yellows amongst the brown umbers and black. The verso – the back - of the painting reveals energetic paint splatters (possibly from other paintings), handling and movement marks from within the artist’s studio alongside the equally impressive signature, AUERBACH, in bold white font indicating the completion of the work.

And yet, as much as high-resolution photography unearths hidden structural complexity, it's only when you look at the work in its entirety and squint that you gain a sense of quiet reflection buried within Head of E.O.W (1955). In this instance, we glimpse E.O.W lost in thought as she sits for countless hours in front of the artist and his easel.

Frank Auerbach sadly passed away on 11th November 2024

- iAuerbach, F (2022) Frank Auerbach: The Sitters. Piano Nobile Publishing, London, pp.26.

- iiSylvester, D (2002) About Modern Art: Critical Essays 1948 - 2000. Pimlico Publishing, London, pp.172.iii

- iiiLampert, C & Auerbach, F (2015) Frank Auerbach: Speak and Painting. Thames & Hudson, London, pp.50.

- ivAuerbach, F (2022) Frank Auerbach: The Sitters. Piano Nobile Publishing, London, pp.26.

This article was written by James Milne, with photography by Rhian Israel.

James Milne is an Art Technician for CELF, the national contemporary art gallery for Wales, who is passionate about working with the national art collection. He is also a practising artist with a particular interest in the complex relationship between art and architecture. James is also undertaking a practice-led PhD at the University of South Wales.

Rhian Israel is a Cultural Heritage Photographer for CELF and is based at Amgueddfa Cymru. She is passionate about making art accessible to everyone and capturing visually engaging imagery, to tell the story of our National Collection.

You may also be interested in:

Share

More like this

The National Library of Wales

Phoebe Murray-Hobbs, Community Loans Officer, National Library of Wales

Imogen Tingey, Exhibitions Assistant, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery

Andrea Powell, Exhibitions Assistant, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery

Sarah Bayliss, Senior Paintings Conservator, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Mari Elin Jones, Interpretation Officer, National Library of Wales

Ffion Rhys, Curator and Elin Vaughan Crowley, Artist - Aberystwyth Arts Centre

Carys Tudor, Digital Curator: Art, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Andrew Renton, Head of Design Collections, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Carys Tudor, Digital Curator: Art, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Nicholas Thornton, Head of Fine and Contemporary Art, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Carys Tudor, Digital Curator: Art, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Jennifer Dudley, Art Collections Management and Access Curator, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales

Sara Treble-Parry and Steph Roberts

Carys Tudor, Digital Curator: Art, Amgueddfa Cymru - Museum Wales