What was ‘New British Sculpture’?

Read on to find out more about this not-quite art movement, the sculptors involved and relevant works in our collection at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales.

Who were they?

The New British Sculptors, whose work was widely exhibited and celebrated throughout the 1970s and 1980s, were loosely grouped together based on factors like their age, where they went to art school and their social links to each other, rather than because their work was visually similar. Unlike other art movements, they didn’t have a shared ideology or manifesto and were brought together by curators and art critics, rather than self-identifying as a group.

The New British Sculptors’ materials ranged from plastic to wood, to metal, to pure pigment; their works were often abstract, though not always. Although the group were diverse in their approach to sculpture, they were united in how they expanded the potentials of this medium – by introducing figurative images alongside abstraction or by choosing to work with a mix of traditional and new sculptural materials and techniques.

Key figures of this group included Stephen Cox, Tony Cragg, Barry Flanagan, Antony Gormley, Richard Deacon, Shirazeh Houshiary, Anish Kapoor, Alison Wilding and Bill Woodrow. These artists were promoted as representing the best of new British sculpture and exhibited together widely both nationally and internationally.

What was ‘new’ about them?

The generation of sculptors that came before New British Sculpture were heavily influenced by Anthony Caro, who taught at St Martin’s School of Art. Caro’s own sculptural work of the 1960s was often made of metal, profoundly abstract, characterised by its large scale, direct placement on the floor (instead of on a plinth) and use of flat, artificial colour. A select group of his students at St Martin’s also began to work in this way – favouring welding and assembly over more traditional casting and modelling techniques, strong and artificial colours over natural ones and new sculptural materials such as scrap metal and fibreglass over more traditional materials such as wood and clay. They became known as The New Generation.

New British Sculpture, a style which emerged in the 1970s, was seen as a reaction to the minimalist metal forms of the 1960s and The New Generation. Several of the artists associated with New British Sculpture – including Richard Deacon, Barry Flanagan and Anthony Gormley – attended St Martin’s, though their work does not reflect the Caro tradition.

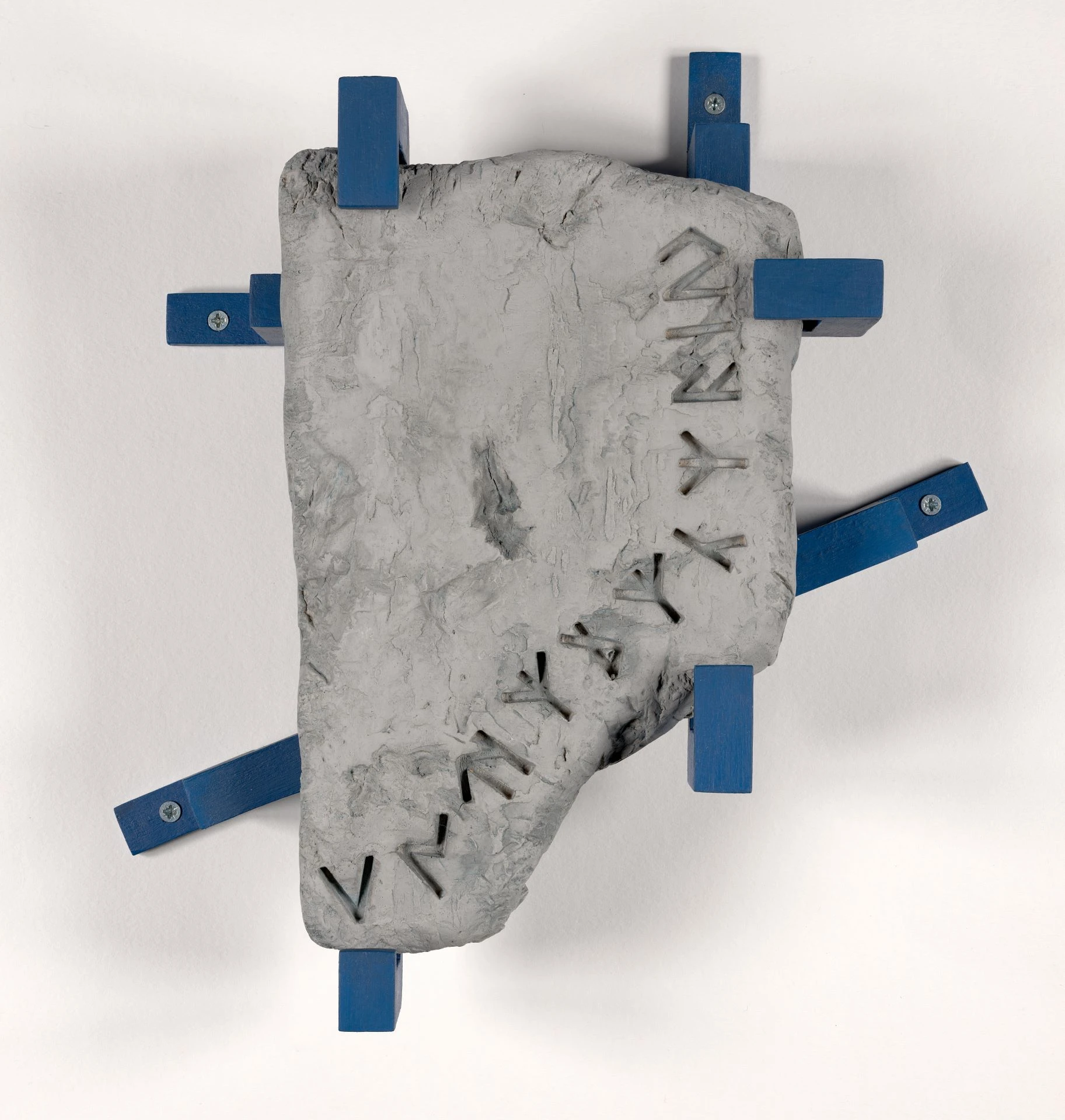

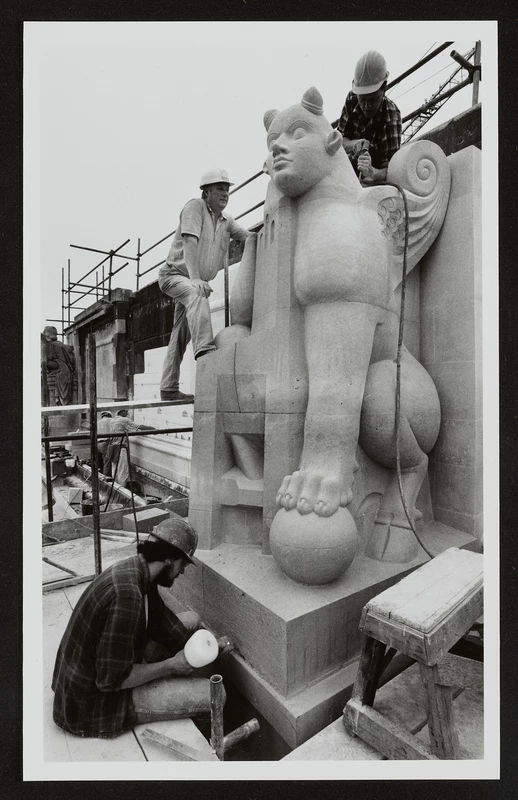

In reaction to this minimal and conceptual art style, the New British Sculptors adopted a more traditional approach to materials, techniques and imagery, focussing on the materials and processes used in fabricating sculpture. For example, Richard Deacon purposely didn’t use welded steel in his practice, preferring materials like fabric, lino and wood. Where Deacon did use steel, it was galvanised and fabricated with joins and rivets, showcasing his process of creating the sculpture. Deacon describes himself as a ‘fabricator’ rather than an artist, emphasising the construction behind each of his finished objects.

How did they become so successful?

Most of the figures linked to this moment in British art were represented by the privately funded Lisson Gallery. Lisson Gallery owner Nicholas Logsdail was highly supportive of New British Sculpture and used his position as a prominent figure in the art world to nurture the careers of this new generation of young and ambitious artists. Though it would later become common for commercial gallery owners to have an art school background, at the time, Logsdail, who opened the gallery out of his semi-derelict home in 1967 while still a painting student at the Slade, was distinct because of his first-hand experience of the art world and knowledge of other young artists.

The early 1980s saw several significant surveys of the New British Sculptors, including two landmark exhibitions: Objects and Sculpture at London’s ICA and the Arnolfini in Bristol (1981) and Figures and Objects: Recent Developments in British Sculpture at John Hansard Gallery in Southampton (1983). Three young curators – Iwona Blazwick and Sandy Nairne at the ICA and Lewis Biggs at the Arnolfini – brought together the artists for the first of these exhibitions, based on personal contacts and studio and exhibition visits. Such group exhibitions were crucial in the promotion of these emerging artists and worked as a tool for drawing wider public attention to their work.

Further high-profile organisations such as the Tate, the Arts Council and the British Council, were also supportive of this new style of sculpture, thus enabling the work of the artists associated with it to be seen in major institutions and exhibitions in the UK and internationally. After the Turner Prize was founded in 1984, at least one artist associated with New British Sculpture was shortlisted for six of its first seven years, with three of them – Richard Deacon, Tony Cragg and Anish Kapoor – winning between 1987 and 1991.

What works are in our collection?

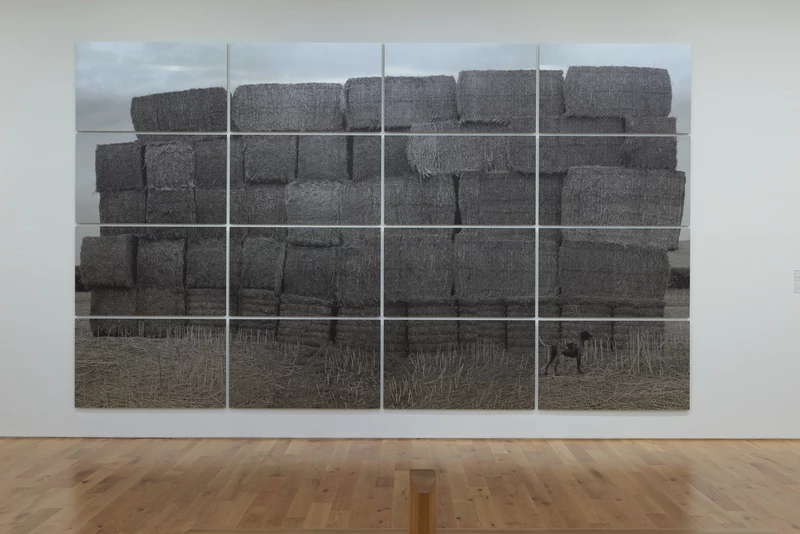

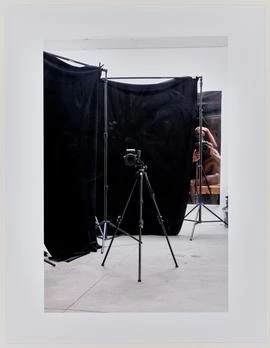

Recently shown at venues across Wales as part of Celf ar y Cyd…on tour, Richard Deacon’s Tall Tree in the Ear was voted one of our Instagram audience’s favourite works in 2020. Welsh-born Deacon is an internationally important sculptor, brought to prominence through his association with New British Sculpture. He has described Tall Tree in the Ear as having a “satisfactory elegance”. The two elements wrap together but are not physically attached to each other. The wooden construction, enveloped in blue canvas, loops underneath the galvanised steel shape, while the top edge of this shape has a missing piece that springs apart to act as a grip, embracing the blue loop. Both elements are abstract, rather than representational. The sculpture’s focus is its own construction and the relationship between its two different elements.

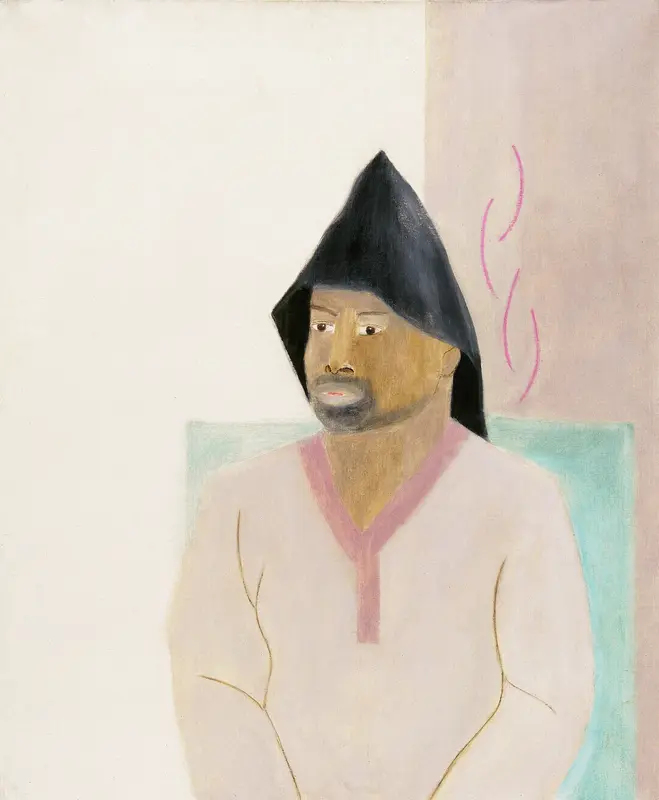

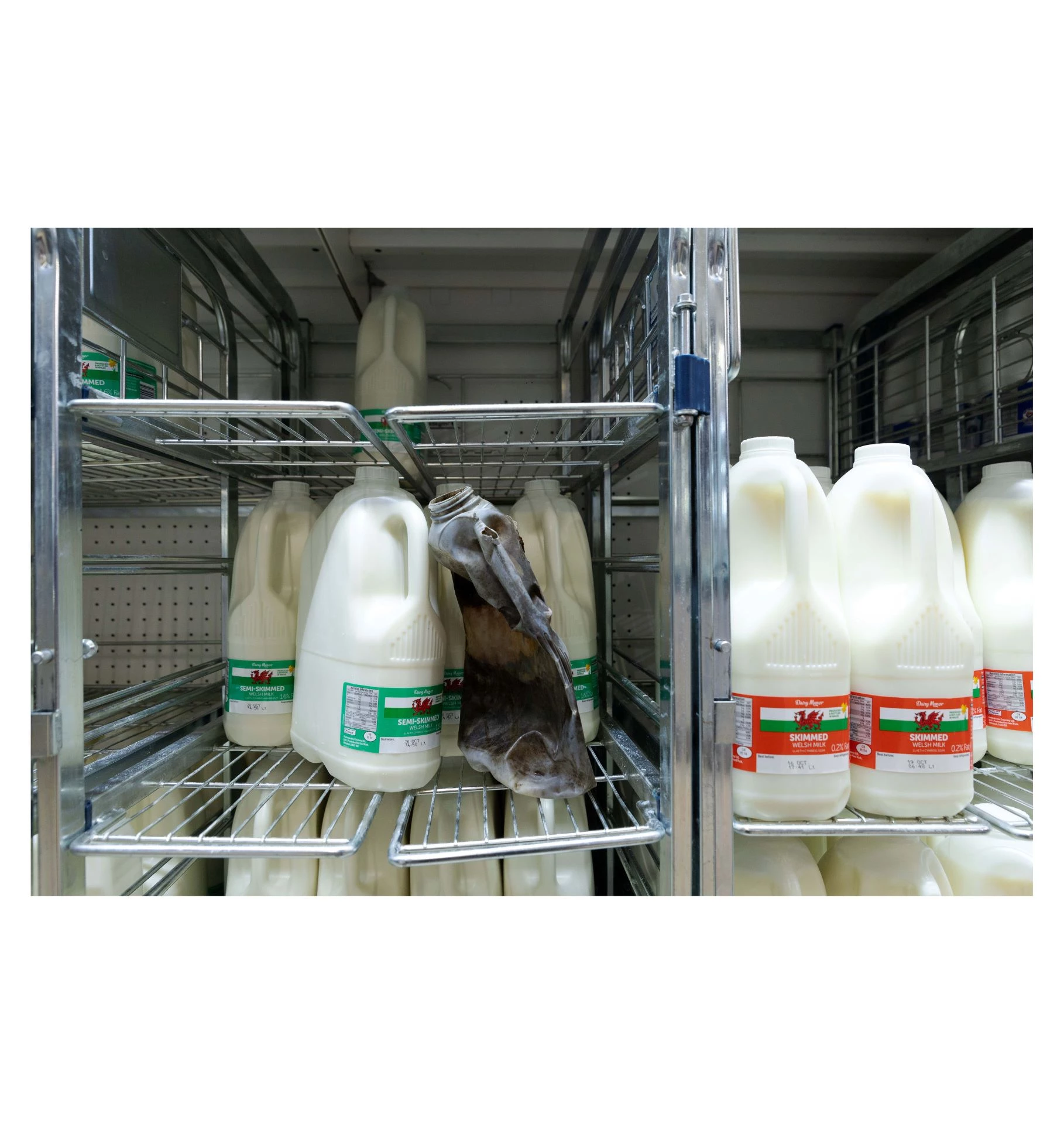

Bill Woodrow, also linked to New British Sculpture, is known for recycling discarded domestic goods and fashioning them into new sculptures. In the early 1980s, he built his reputation on a series of ‘cut-out’ sculptures, manipulating and transforming the metal surface of a household appliance into another familiar object without detaching it from the original. In The Red Hat, Woodrow has done just that – extracting the form of a violin and bow from an old metal spin dryer. Recycled sculptural materials, often taken from either the skip or the studio floor, were a significant part of many of the New British Sculptors’ practices. Similarly to Deacon’s work, the materials and processes are a central subject of this work. However, it is decidedly less abstract.

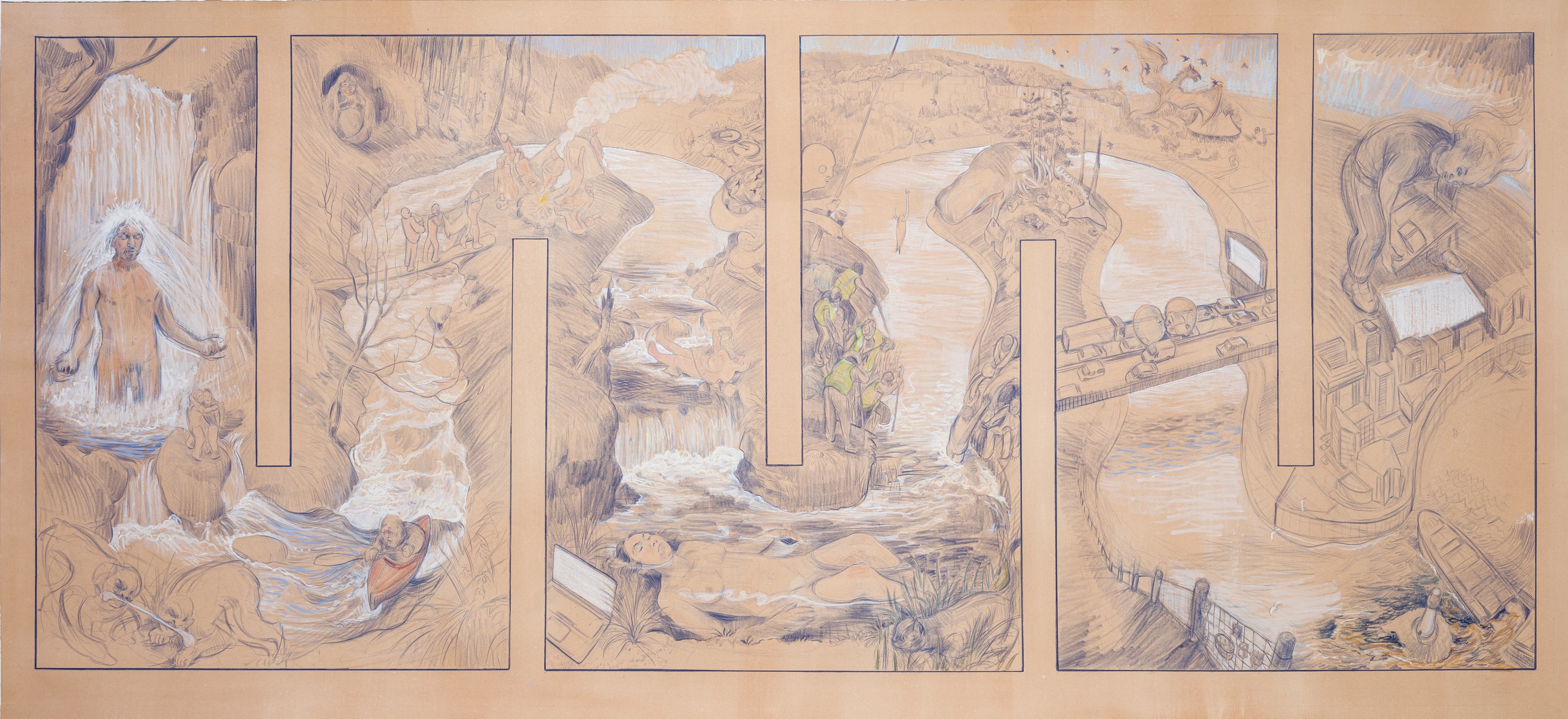

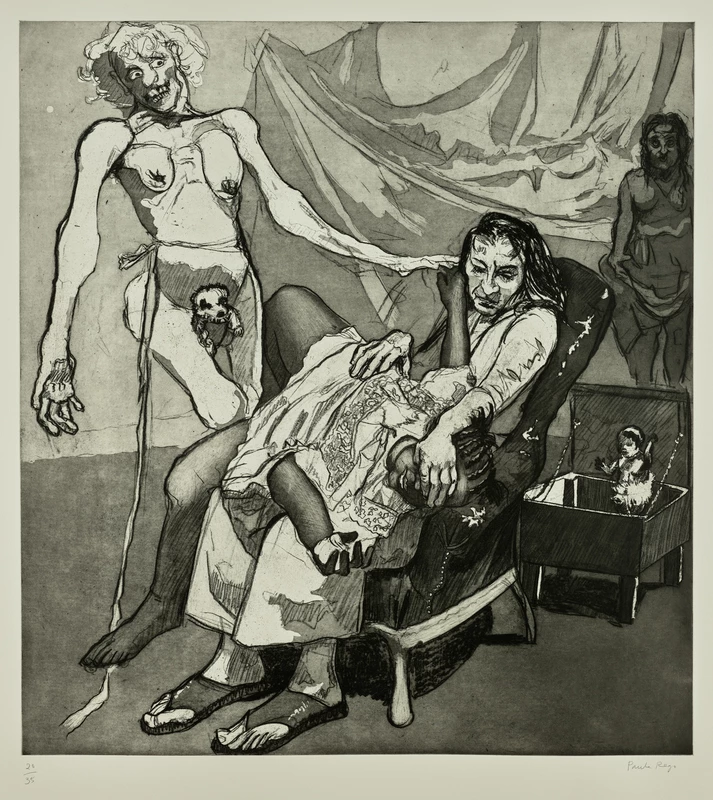

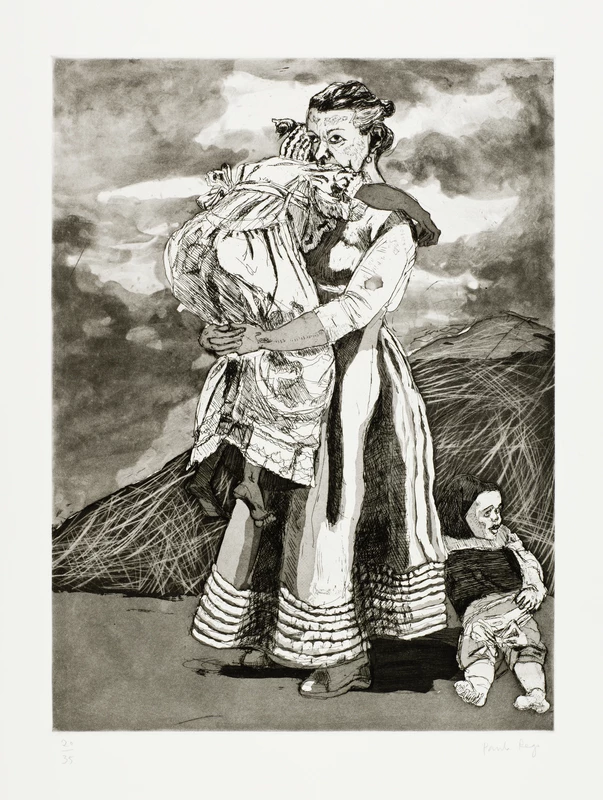

Finally, let’s take a look at Barry Flanagan’s Small Nijinsky Hare. This figurative bronze work is much closer to the traditional materials and forms of sculpture. The long-limbed hare elegantly mimics a classic ballet pose by standing en pointe on its right leg with its knee bent and the left leg bent and raised in front. The Irish-Welsh sculptor Barry Flanagan started sculpting hares in the late 1970s, moving away from conceptual art and towards figuration. This work is modelled after the ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, a celebrated member of the Ballet Russes who was renowned for his gravity-defying leaps. The heavy and static material of bronze has become full of life, lightness and movement.

What do you think – what are the similarities and differences between these three sculptures from our collection?

Dr Jennifer Dudley is now the Collections Management and Access Curator at Amgueddfa Cymru, having previously worked as a Curatorial Intern and the Derek Williams Trust Collection Curator (Maternity Cover) at Amgueddfa Cymru. In 2021, Jennifer completed her PhD on late-twentieth-century abstract sculpture.

FLANAGAN, Barry, Small Nijinsky Hare © Artist Estate / Bridgeman