The Beauty of Imperfection

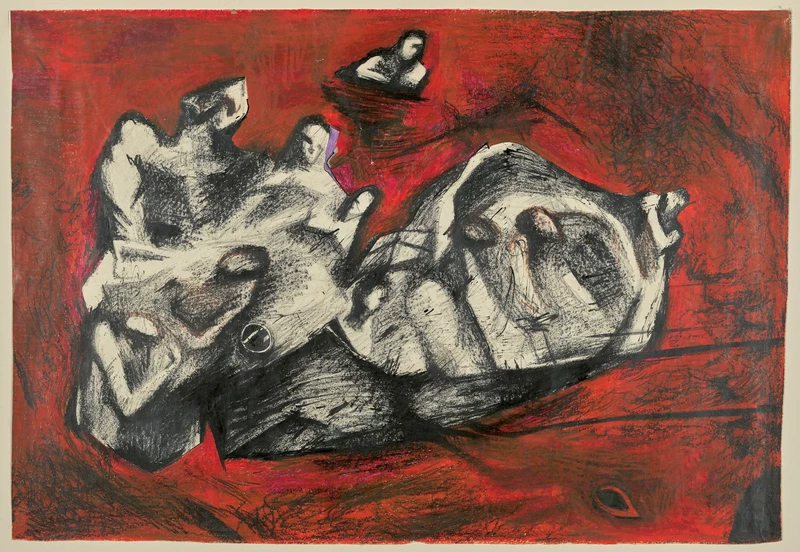

In a world where tears for shattered dreams do fall,

Broken thoughts and things, they haunt us all.

Yet within each fracture, hope’s ember starts to burn,

Beauty in imperfection, a lesson we must learn.

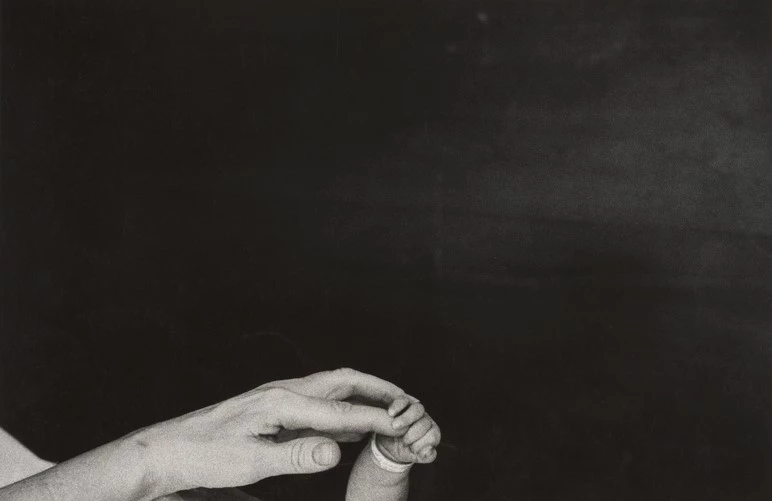

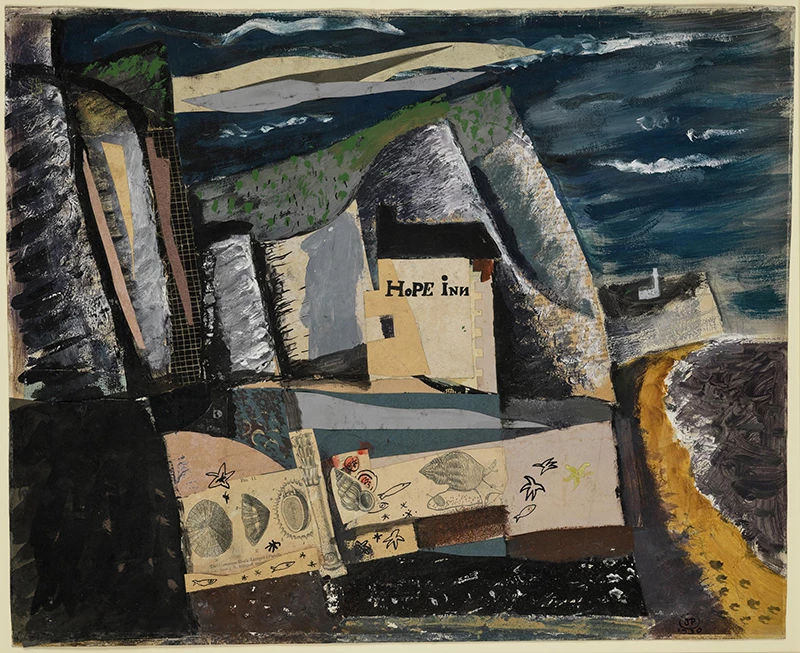

Imagine frozen moments, stories caught in a frame,

Greek script and love’s essence, not just a mere claim.

In pixels and verses, emotions softly lace,

A Mother’s love torn, a timeless embrace.

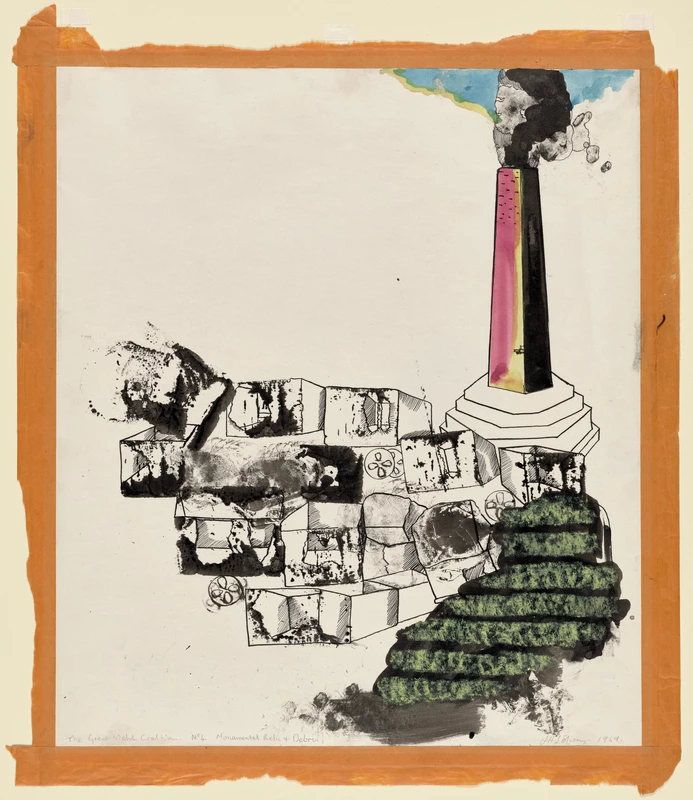

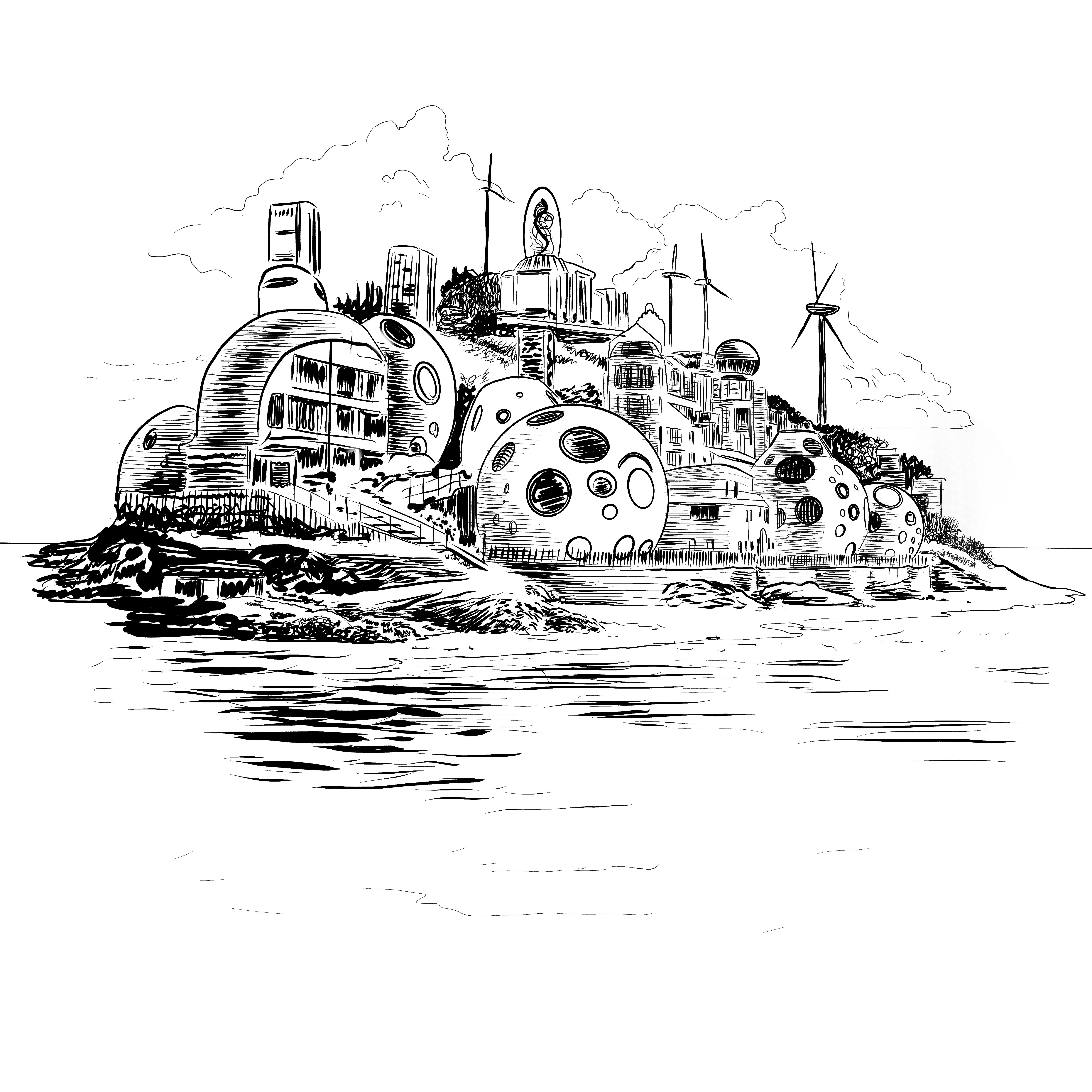

Now envision the remnants of castles once grand,

Their missing glaze, a masterpiece unplanned.

Cut edges gleam with life’s wisdom worn,

Like unfiltered moments, where authenticity is born.

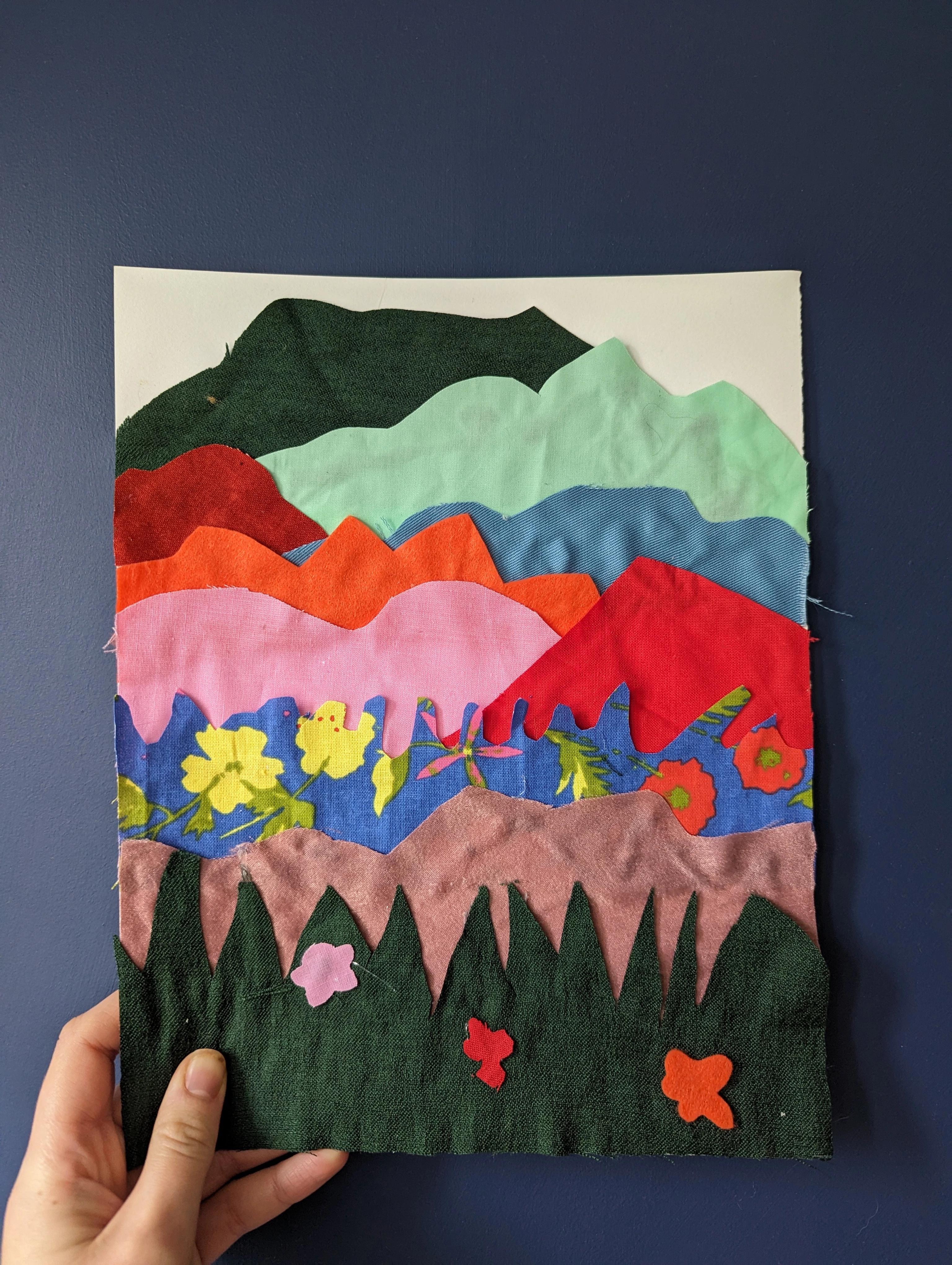

In this fabric of existence, we seek what’s true,

Genuine souls and moments, a precious view.

Within these life’s fragments, stories unwind,

Revealing the beauty of imperfections, one of a kind.

So, within life’s rich tapestry, these tales reside,

Of brokenness and beauty, hearts open wide.

Through trials and tears, our spirits start to glow,

In the fragments of existence, our true selves begin to show.

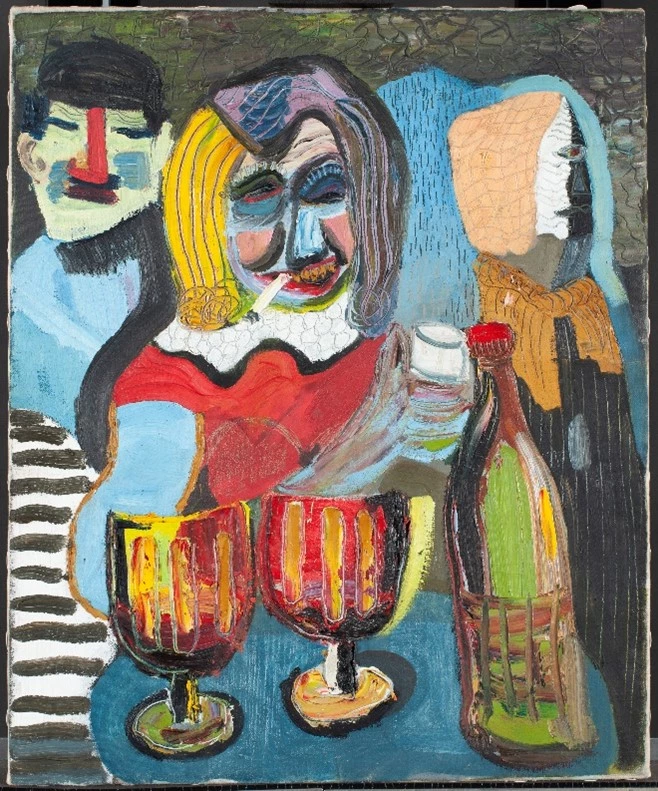

Broken yet Beautiful

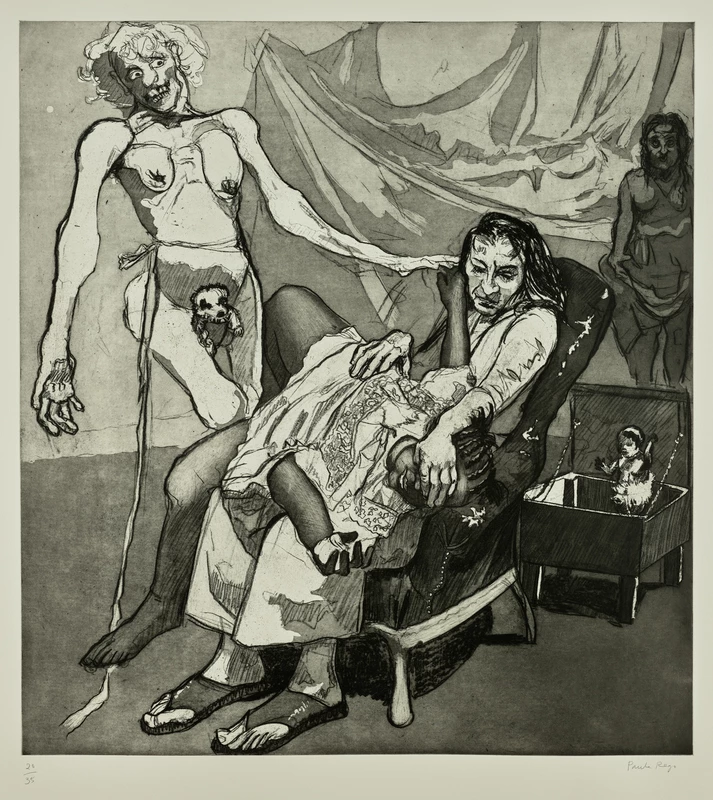

Broken yet Beautiful, there is a certain allure in the imperfections, akin to a fractured object that, when mended with gold lacquer, becomes more precious than its original state. This notion applauds resilience and the capacity to discover beauty amidst challenges.

We generally neglect and throw away broken objects, but rarely think of how beautiful they look.

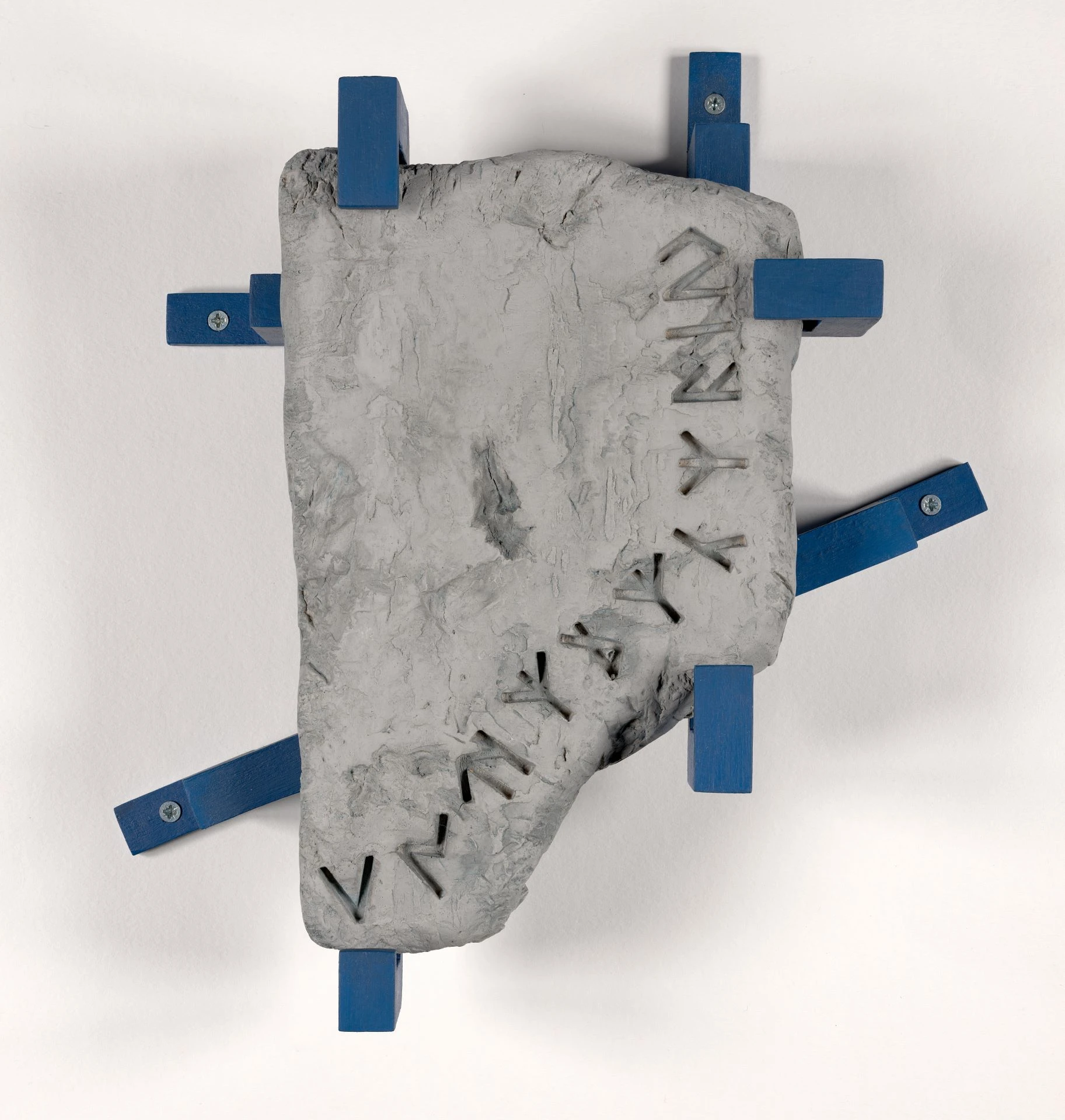

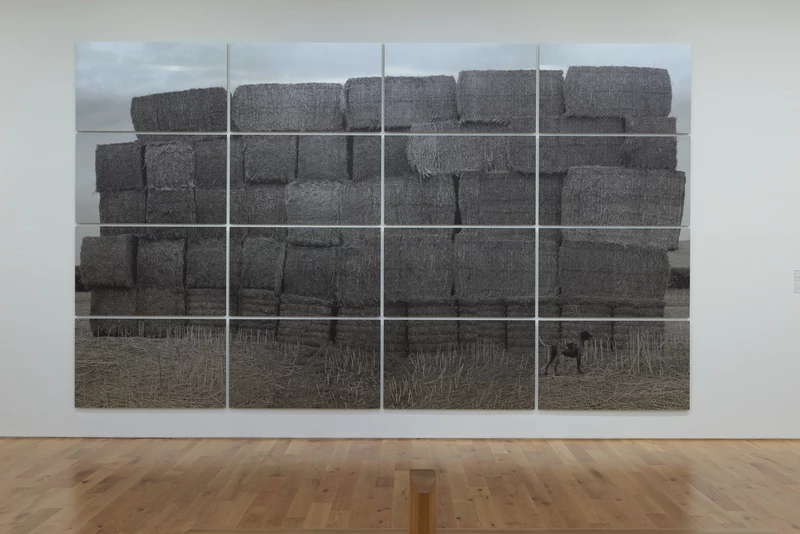

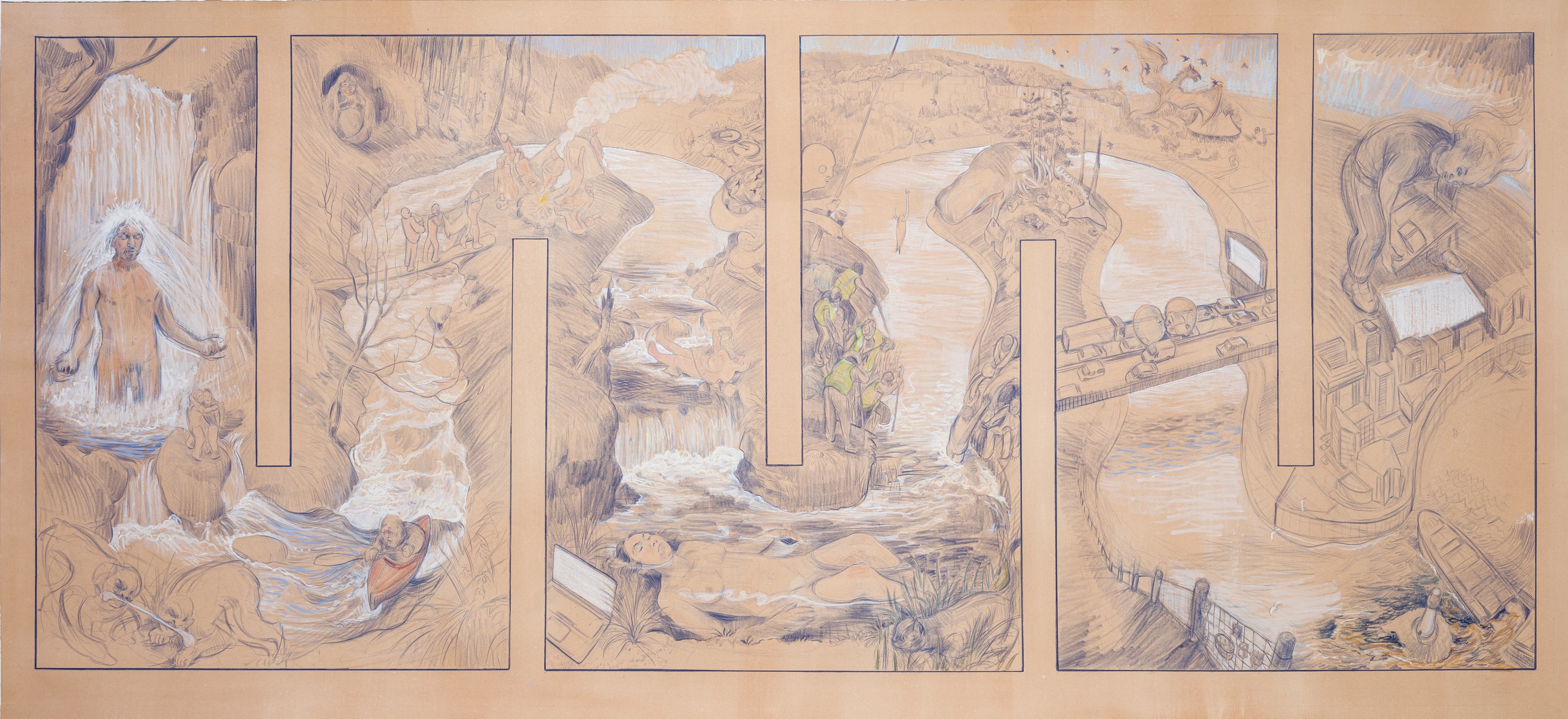

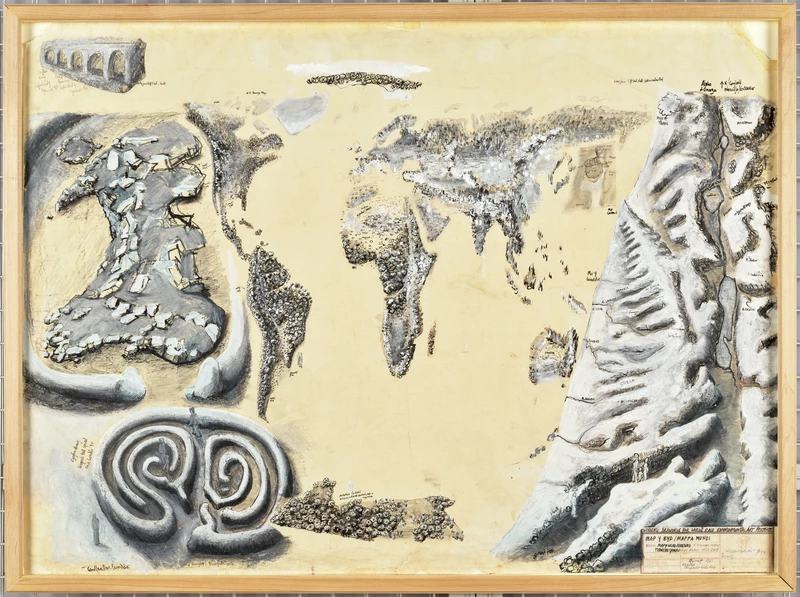

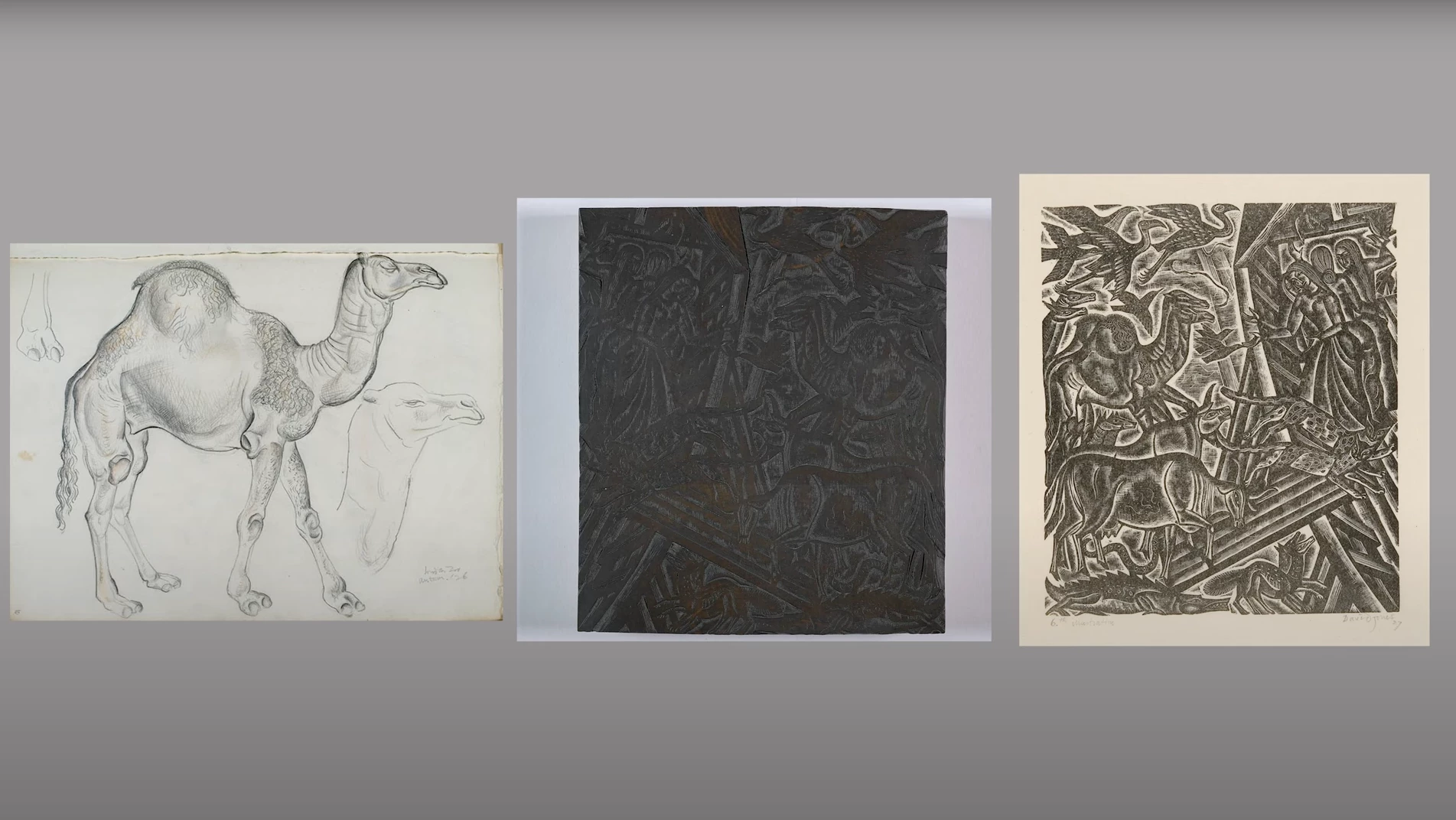

Upon rediscovering the old ceramic collection buried underground, we have unearthed a fascinating array of items. Some are impeccably crafted, while others bear the scars of time, evident in the three pieces of damaged pottery placed prominently amidst the sea of white shards. What makes this excavation even more intriguing is its ongoing nature. Take a moment to observe the vibrant, colourful fragments adorning the white shards. Surprisingly, these captivating pieces are not remnants from the ground but broken objects discovered elsewhere. The three distinctive pieces in the collection’s front describe their excavation process. The white pieces that represent the earth and the dominant neighbouring object stand out in contrast to them.

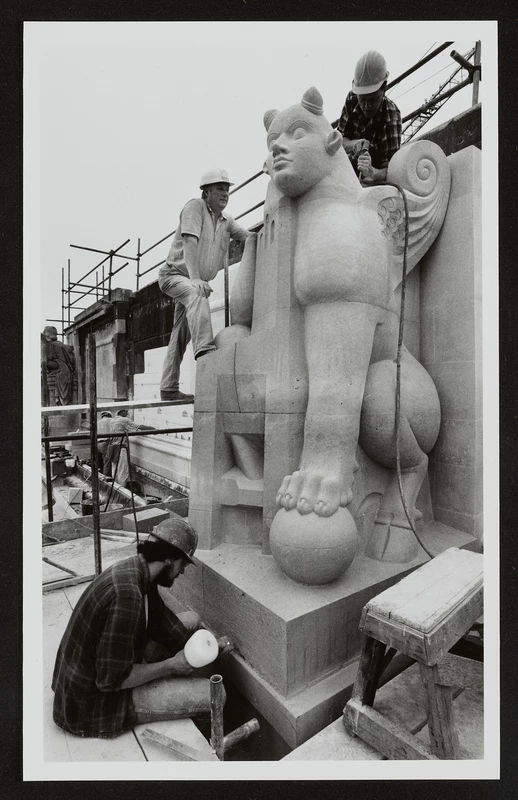

This tile is from Tintern Abbey in Monmouthshire. It was given to Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales by John Ward, the Keeper of Archaeology, who most likely removed it from the location in the early 20th century. This tile is recognised as a member of the Wessex School, a group of artefacts whose distribution pattern corresponds with the Wessex region or a section of it. The tile’s broken edge caught my attention the most as it depicts an ancient lion passant contour with a fleur-de-lys in a circle in its raw form.

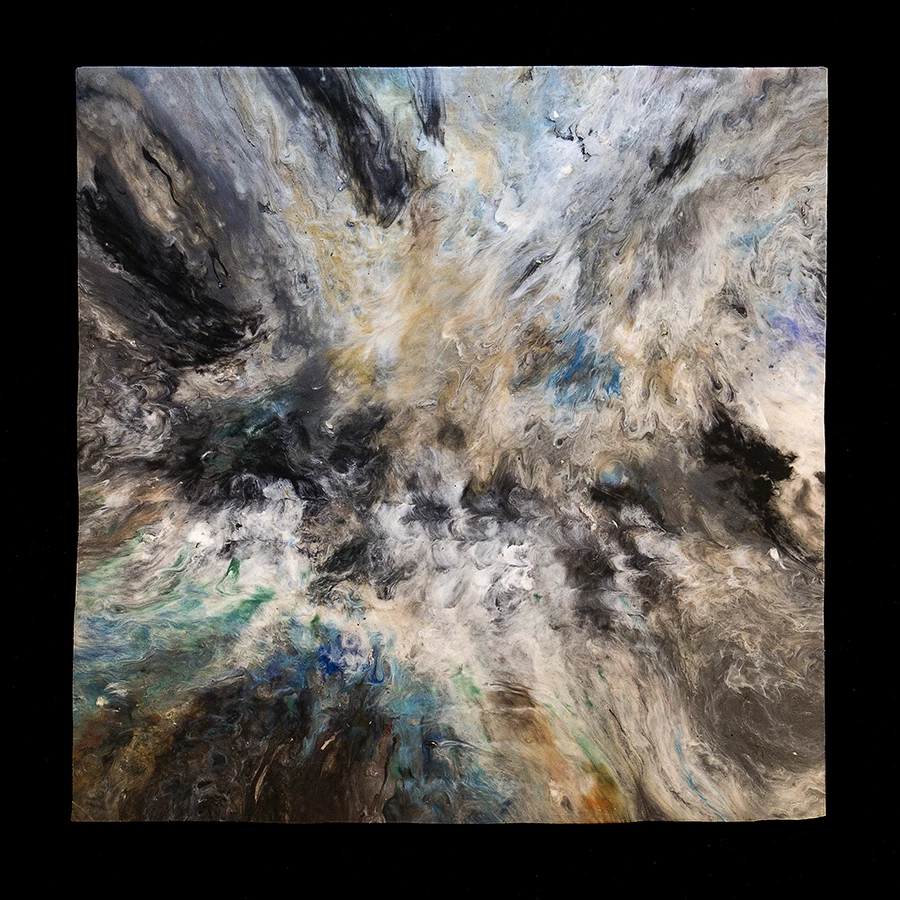

This one is from Dunraven House, a medieval manor house in the Vale of Glamorgan that was expanded through time until it was demolished in the 1960s. It is also often referred to as Dunraven Castle. The same area is home to the now privately owned medieval stronghold known as Benton Castle. In the 1930s, the castle’s previous owner contributed more than 200 pieces of pottery from the medieval and post-medieval eras to the Amgueddfa Cymru collection. This dish is composed of Staffordshire-style slipware, with a combed surface, possibly rectangular shape, and pie-crust polished edges. When I first saw it, I immediately thought of marble cakes, and I then wondered if perhaps the design of today’s marble cakes was inspired by anything similar.

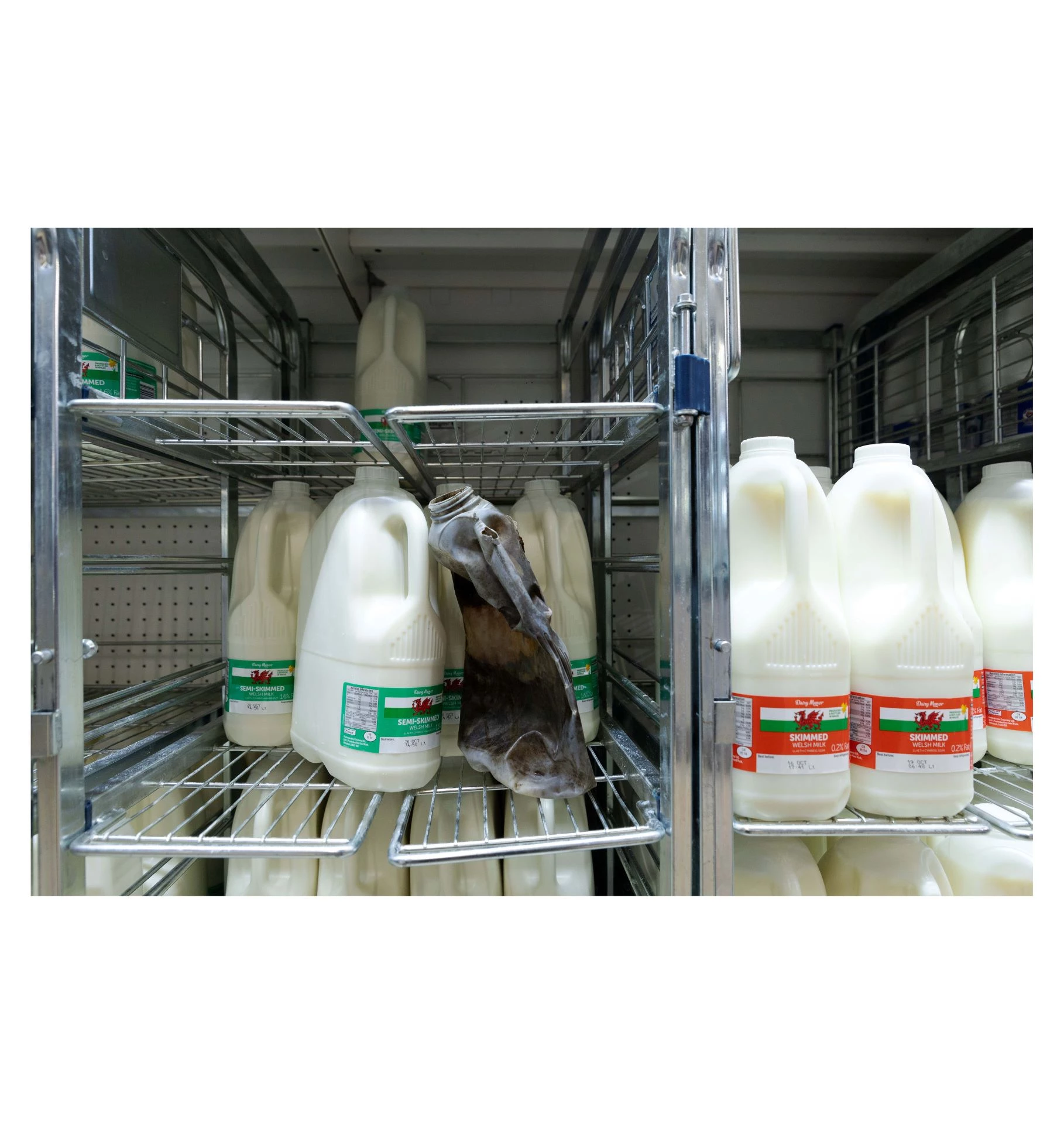

Additionally, here is a shattered piece from a plant pot that may have been purposely left unglazed. It is an Ewenny slipware rim sherd where the glaze is absent. The created pattern resembles a simple brushstroke. I adore how unprocessed the post-production and brushstrokes are.

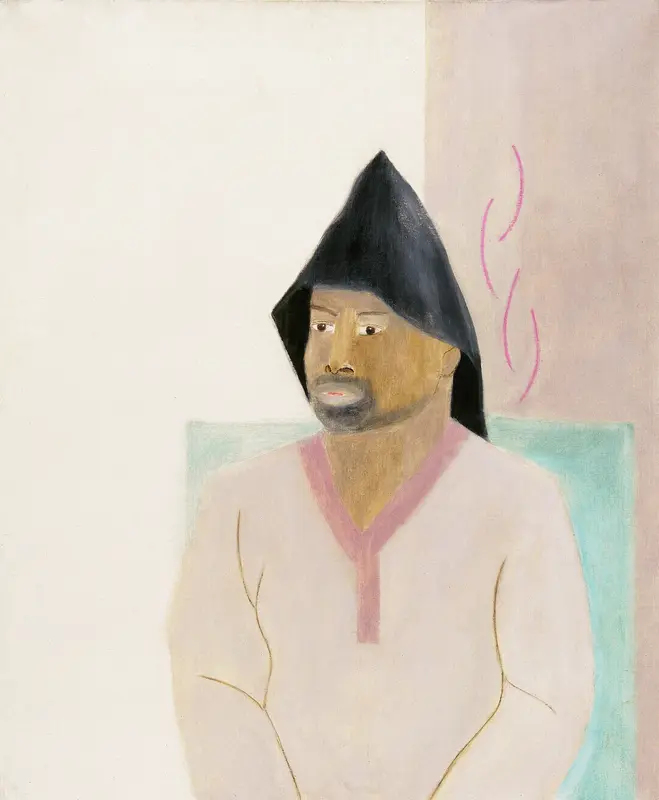

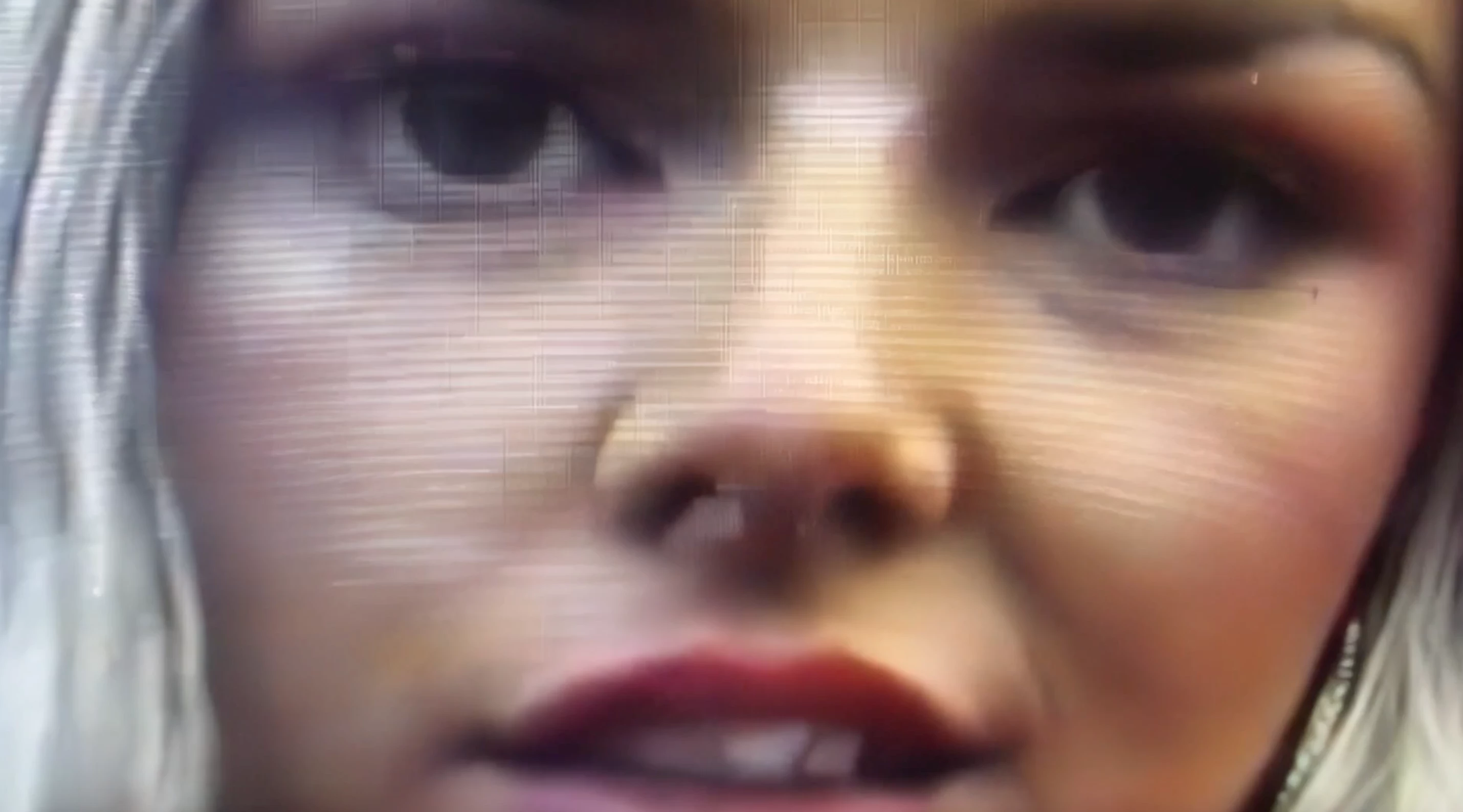

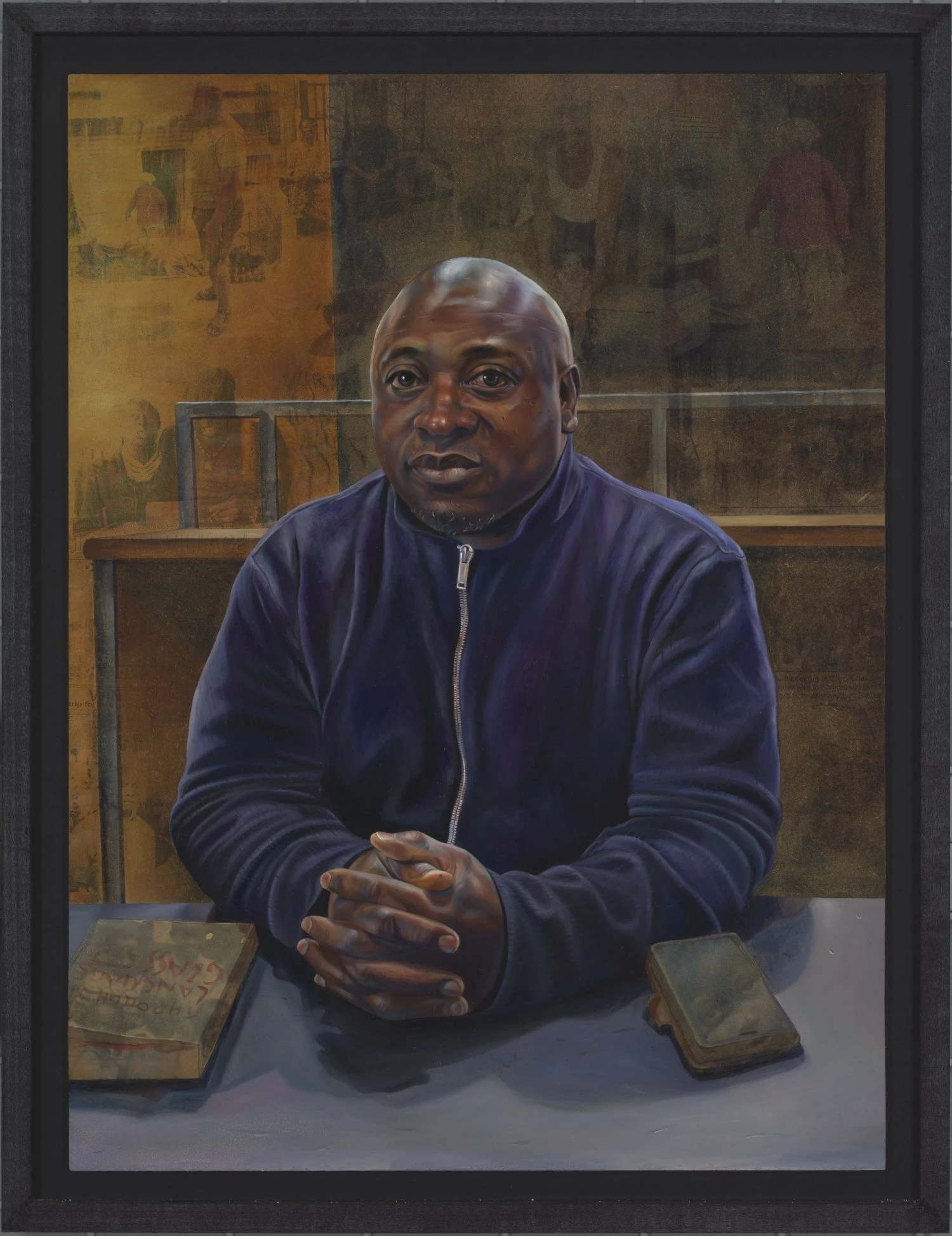

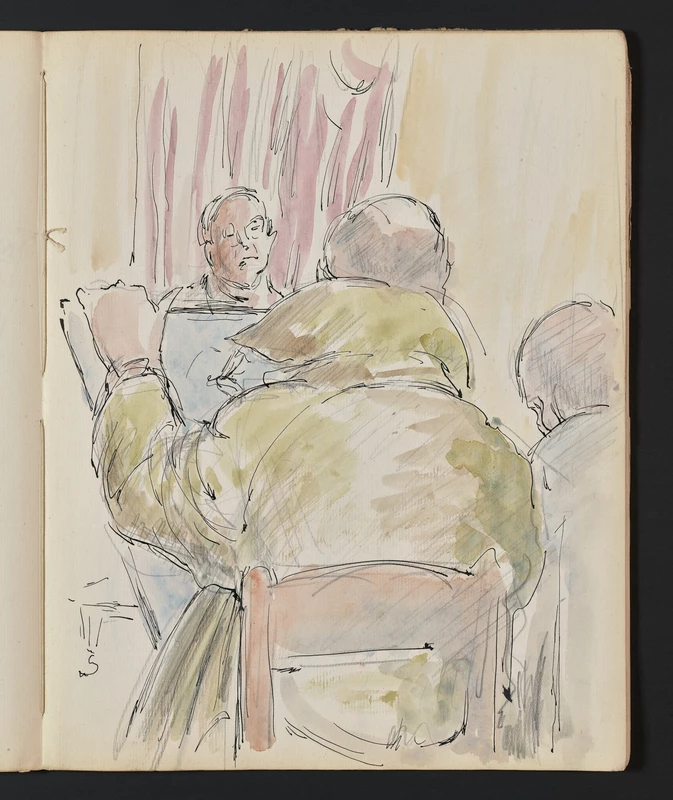

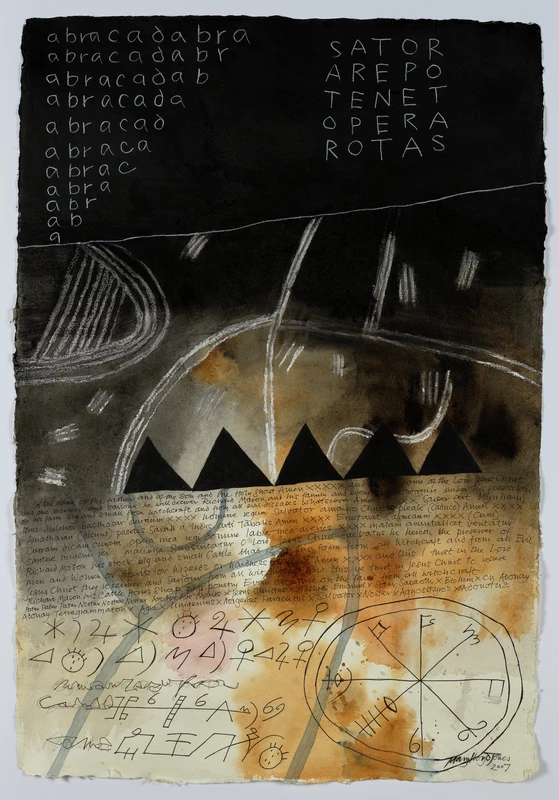

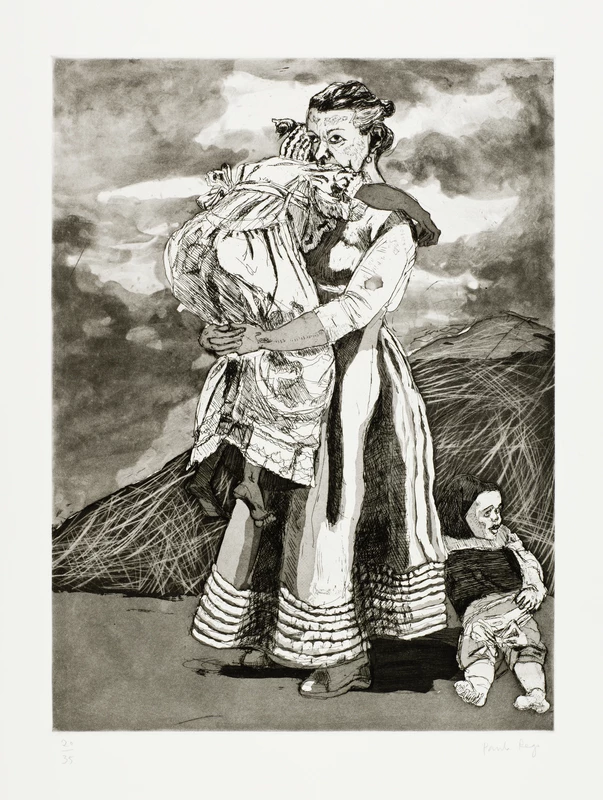

Coming to the main object: a dish, made of earthenware, with a matte cream surface, a round foot ring, curved edges, and a transfer-printed decoration. Torn in Two by Antonia Splini features an image torn in half of a woman holding a baby that has been overlaid with Greek script from an unidentified letter. Even though it isn’t shattered, the picture in the dish conveys a lot about the bond between a mother and child. The text on the picture seems torn apart, and it appears to be tied to an old photograph of the two of them. To me, this looks like a message from the child to the mother.

The Sounds of Ceramics

In April 2023, Amgueddfa Cymru’s Bloedd group held a workshop called Talking Pots, exploring the sounds of ceramics; regrettably, I was unable to attend, but it brought back memories of when I was a child and how much fun it was to play with objects and make funny noises with them. It also brought back memories of when I was in school and how we would make noises during lunchtime with our pens hitting on the desk. Inspired by this idea, I got the notion to experiment with making noises with ceramic objects when choosing the items for my final project display at National Museum Cardiff. To create a soundscape, I gently struck the objects like the shards from Nantgarw, the porcelain vase with eagle handles from Swansea China Works, and Glamorgan Pottery Swansea’s stand for six egg cups with a pen and my fingers while it was resting on various bases made of glass and wood. As I held it in my hand, various sounds began to emerge.

So, experience the magic of sound! In this recording, we explore the qualities of ceramics through the power of sound. Close your eyes, tune in and let the melodies of knowledge and creativity wash over you.

Ever wondered what the life of an intern at Amgueddfa Cymru is like?

I am currently pursuing my MA in Curating at UWE (University of West of England) Bristol, and in February 2023 I embarked on a placement at Amgueddfa Cymru, based at National Museum Cardiff. This opportunity has been a dream come true for me. I was unsure whether this placement would happen last year, but I persisted in wanting to be a part of National Museum Cardiff, and now here I am, presenting my final project.

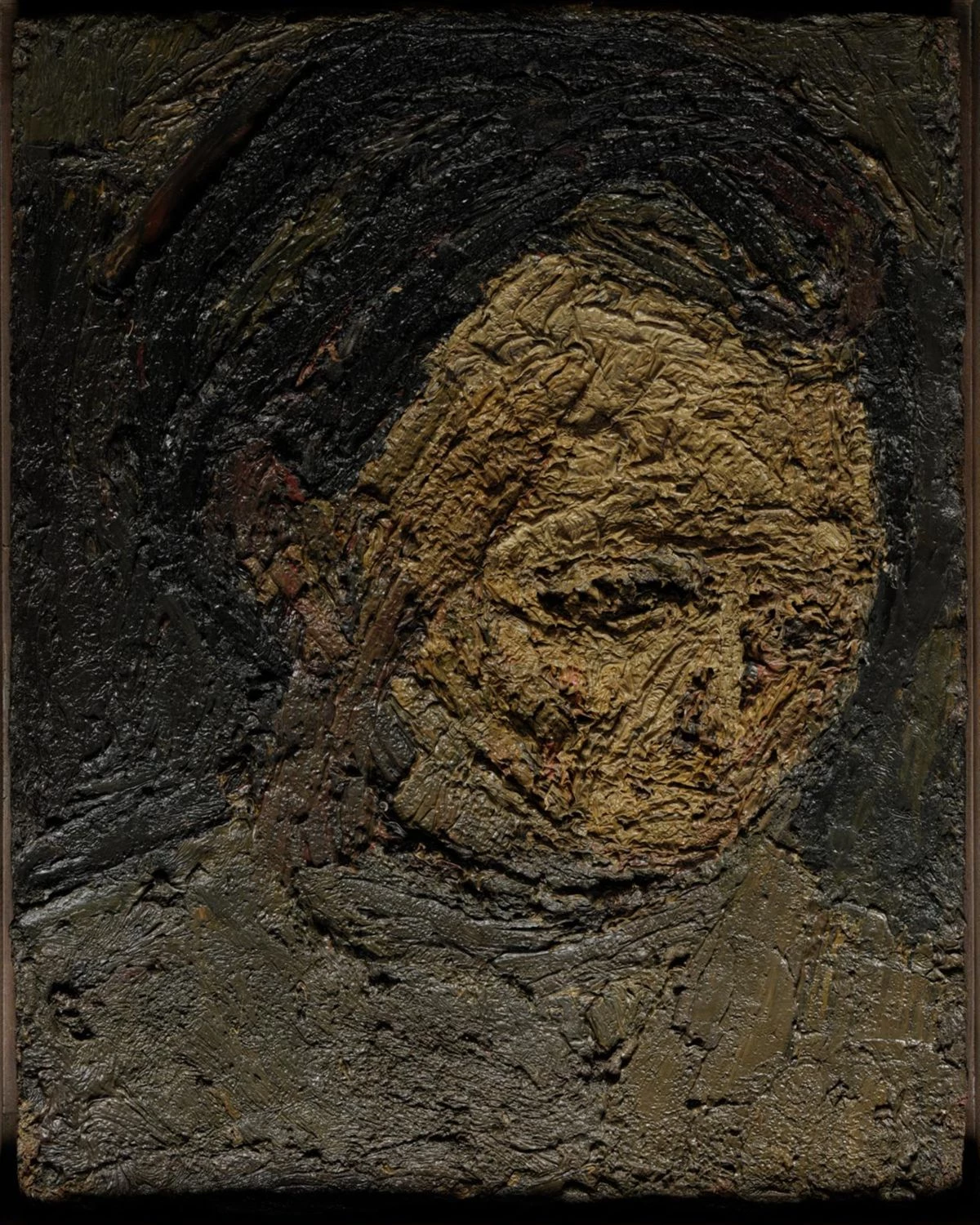

One of the aspects of museum curating that has always captivated me is the beauty of broken objects. In life, it’s often challenging to witness brokenness, but these moments of fragility also showcase our resilience and strength, much like the objects I chose to be displayed for my final project in one of the cabinets in the Museum. Despite being broken, they exude a unique and captivating beauty.

I have always been curious about why I am so drawn to these damaged artefacts and what kinds of stories they are expressing throughout my path in curating. It appears like each crack and chip conceals a story just waiting to be revealed. I am reminded of the human spirit’s tenacity by these artefacts, despite their flaws. They talk about collisions, mishaps, or the passage of time that has left its mark. Much like the human experience itself, every crack conceals a tale of tenacity and survival. These damaged objects, which mirror our own difficult life journey, speak to me as symbols of it. They are more than just historical artefacts; they are storytellers, telling the tales of the individuals who created, utilised, and treasured them. My enthusiasm for curating is fuelled by this intrinsic storytelling element, which also drives me to want to tell these engrossing tales to as many people as possible.

Throughout my placement, I’ve had the privilege of learning countless new things that have expanded my horizons beyond what I could have imagined. The experience has been transformative, providing me with insights and knowledge that I didn’t have before.

Lastly, I’d like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my mentors, Jennifer Dudley and Andrew Renton, whose guidance and support have been invaluable in shaping my journey at National Museum Cardiff. Growth throughout this internship has been significantly influenced by their expertise and mentorship.

Armed with the knowledge and insights I’ve learned so far, I’m eager to continue looking into curating. I’m eager to see where my academic journey goes next because this placement has been a key chapter.