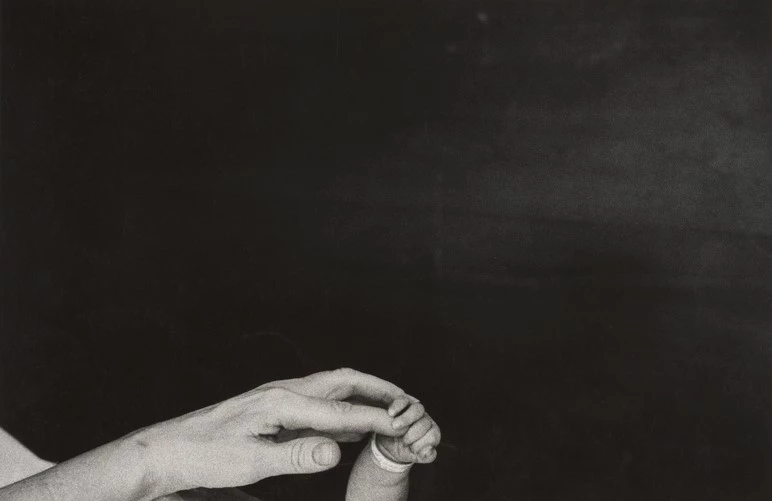

After ‘A Baby’s Momentous First Five Minutes’, by Eve Arnold

After the blood, once the pelvic

scar has narrowed and paled

to a crescent moon, I take

up my camera. Brace for shutters

and makeshift light.

In Port Jefferson, the delivery

room is stark, a metallic tang

wetting the air. We wait,

poised –

and the baby unravels

from the umbilicus, his mother thundering

open. Lowing like a heifer.

And Steven is born.

At one minute old he curls a crinkled

foot towards the ceiling, splays

his toes like tulips. A bracelet is slapped

to each wrist, marked M for male. I watch,

thinking of other M words: mother,

momentous, miscarriage.

By two minutes, his catfish-blue

sheen begins to pink. The cord

already cut to a stump,

he hangs

like a hare

from the nurse’s fist. He is three minutes

old, twenty inches long, strong

enough to crunch his abdominals,

to buck his legs against

gravity’s unrelenting tug.

At four minutes, his father peers

through perspex, smiles his quiet approval:

a boy.

Already his soles have been pressed

to ink, his scalp sponged clean,

his eyes anointed. Already, I have

watched his whole life unfurl

through the lens.

He is five minutes old, swaddled

and laid bare in a plastic cot.

Arm outstretched,

he searches,

finds his mother’s fingertip, clings

to all he knows of the world.

I lower my camera.

Both our lives begin.

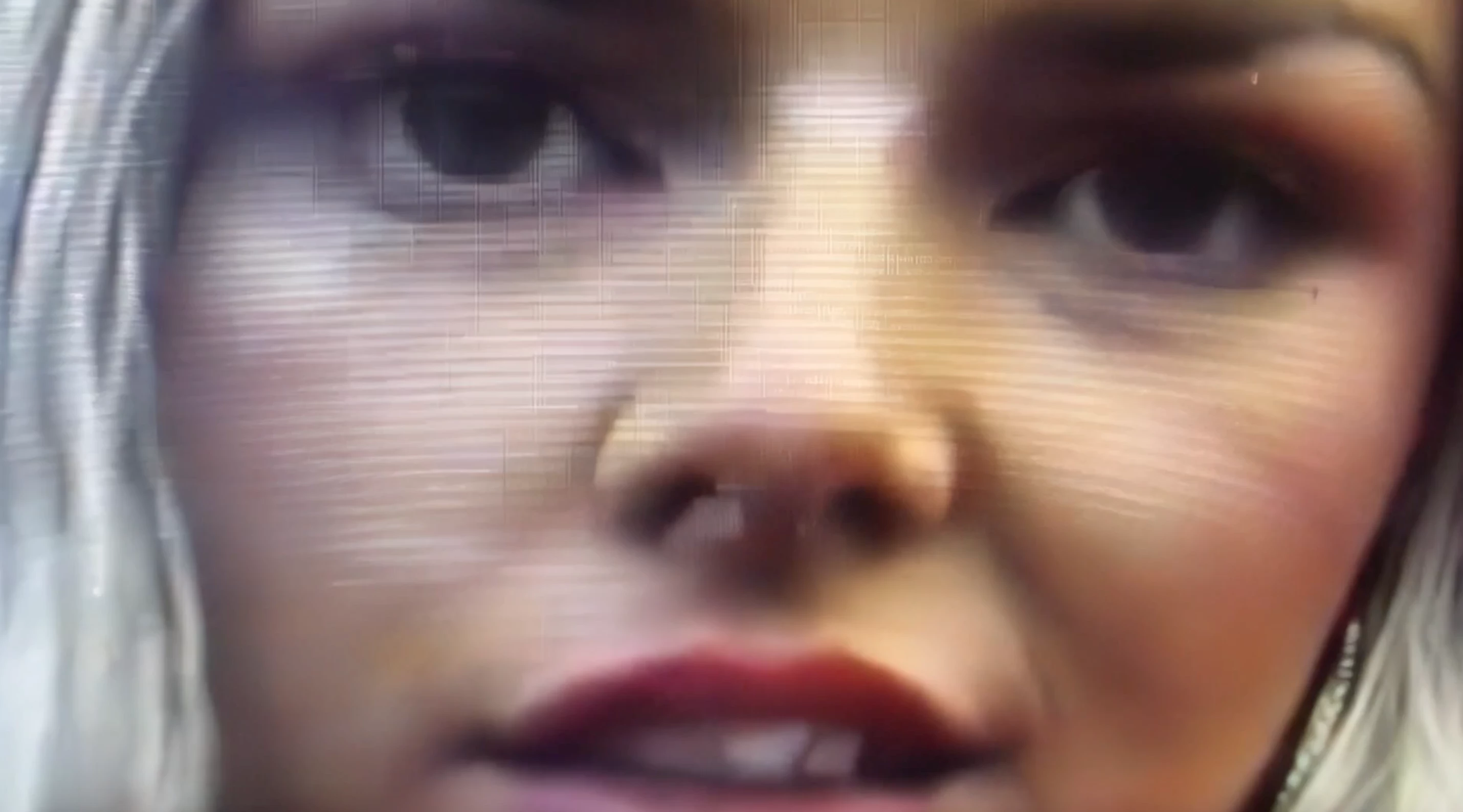

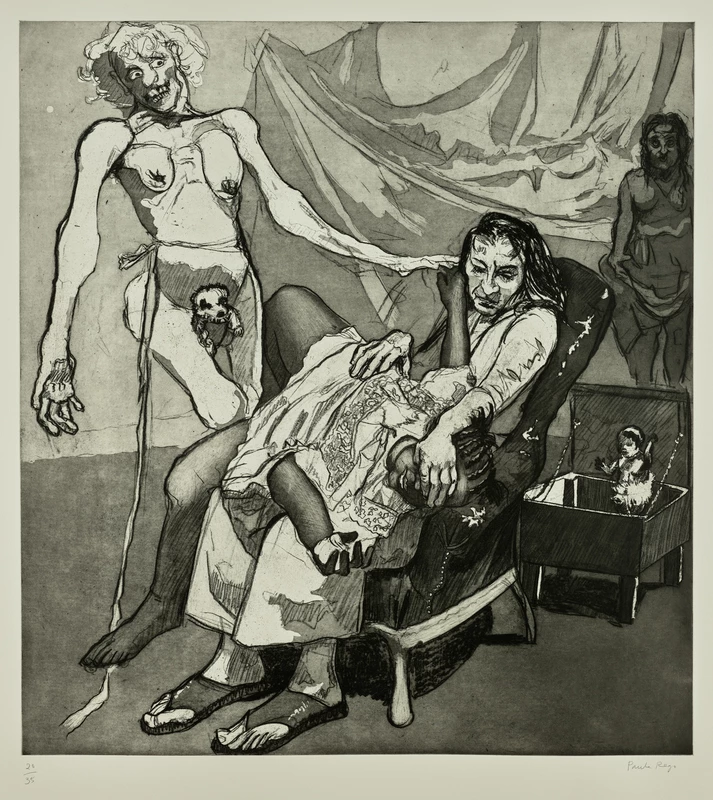

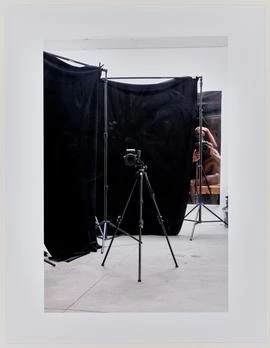

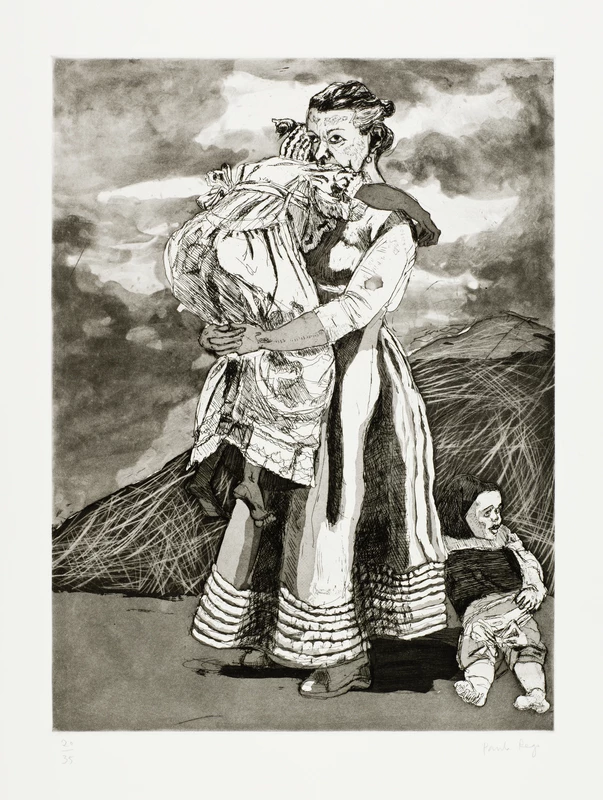

In the late 1950s, Eve Arnold suffered a miscarriage that resulted ultimately in a hysterectomy. The ordeal caused a profound depression, one that she sought to battle in a close up study of the mechanics of birth at Long Island’s Mather Hospital in Port Jefferson over the course of winter 1959. A series of photos from this study, documenting the birth of Steven Woods, were printed in Life magazine in a photo essay titled ‘A Baby’s Momentous First Five Minutes’.

When I learned that Eve Arnold sought to assuage her grief by swathing herself in what she described as the ‘source’ of her pain, it was impossible for the suffering of her miscarriage and subsequent hysterectomy not to colour the poem. The iconic photo depicting new life, a tiny baby clutching his mother’s finger at just five minutes old, was enmeshed with the physical and emotional distress of child loss. For Arnold, participating in the numerous births that ultimately resulted in the famous photo essay, and the iconic shot of the two hands, was a source of healing, a way for her own life to begin anew.

I also wanted to capture the essence of childbirth in fifties America, the strange sterilisation of it – in Arnold’s photos, the baby is immediately slapped, tagged, his footprints captured, weighed, cleaned, measured and anointed. Baby Steven would have been taken away to a nursery to sleep, or to cry in his cot, almost immediately following his birth. There is a striking contrast between the ideal clinical conditions pictured in the black and white photos, and the visceral, bloody reality of childbirth. While there is joy, love and celebration in this photo, there is also sadness and grief. Those two hands, stark against the black backdrop, present a spectrum of human emotion, and I felt it was vital to capture that in the accompanying poem.

Mari Ellis Dunning’s debut poetry collection, Salacia, was shortlisted for Wales Book of the Year 2019. She has since placed second in both the Lucent Dreaming Short Story Competition and the Sylvia Plath Poetry Prize. Pearl and Bone, which was selected as Wales Arts Review’s Best Poetry Collection of 2022, is available from Parthian now. Mari is a PhD candidate at Aberystwyth University, where she is writing a historical novel set in sixteenth-century Wales, exploring the relationship between accusations of witchcraft, the female body and reproduction. Mari lives on the west coast of Wales with her husband, their two sons, and their very adorable poochon.