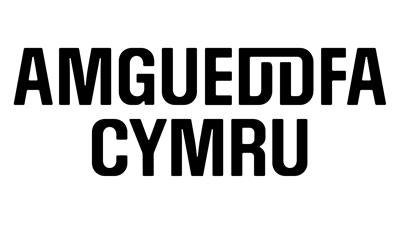

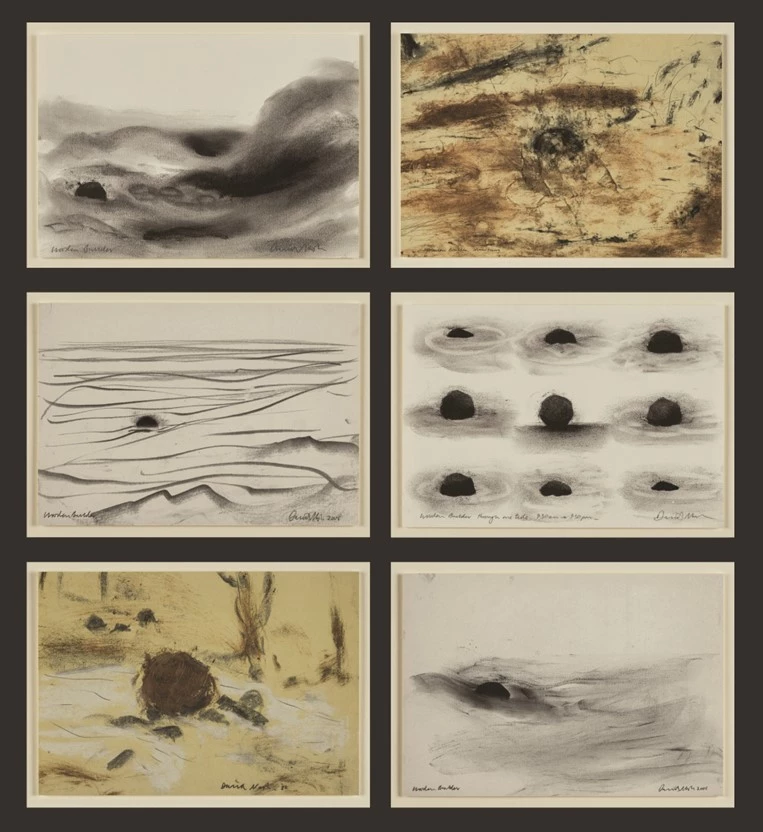

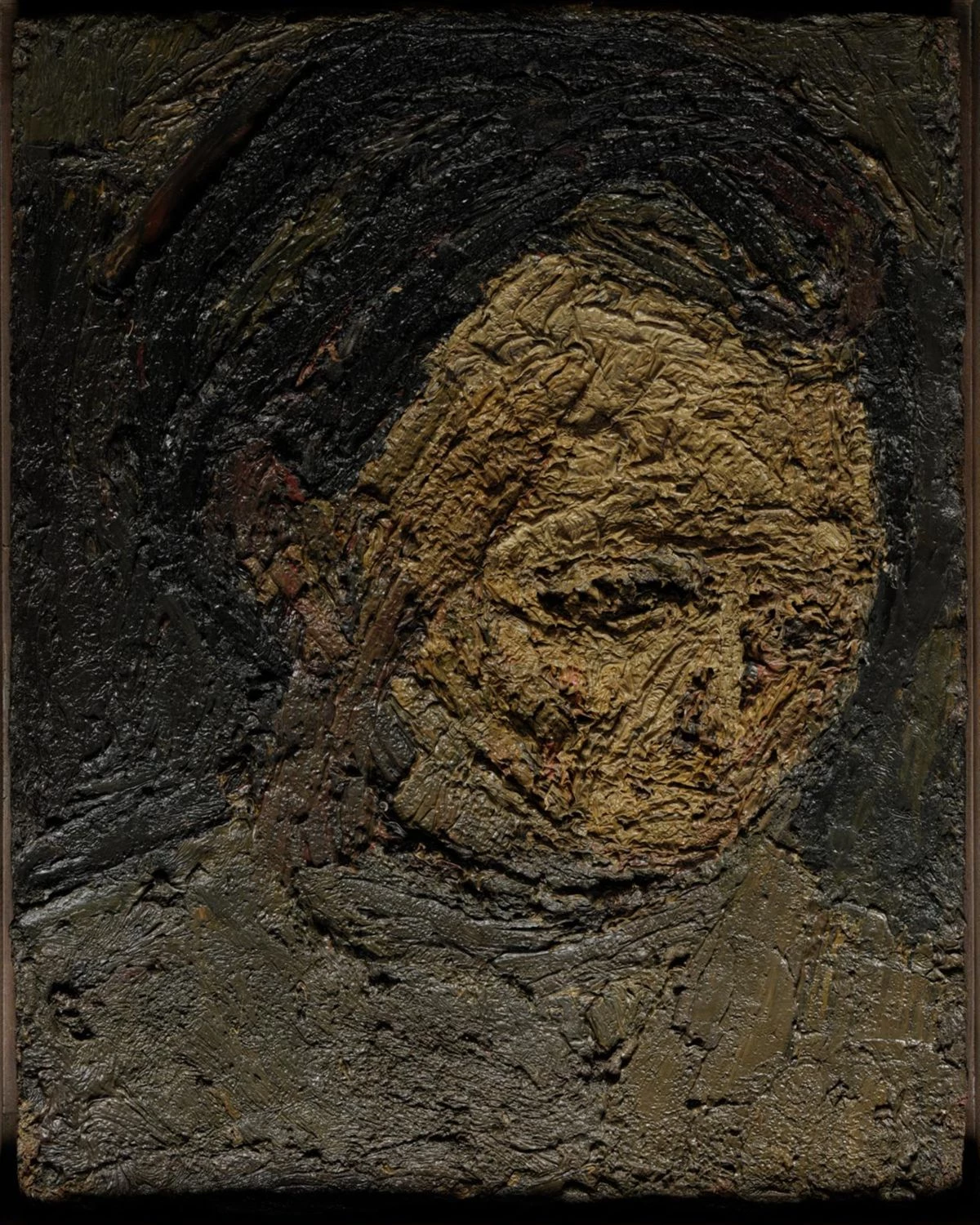

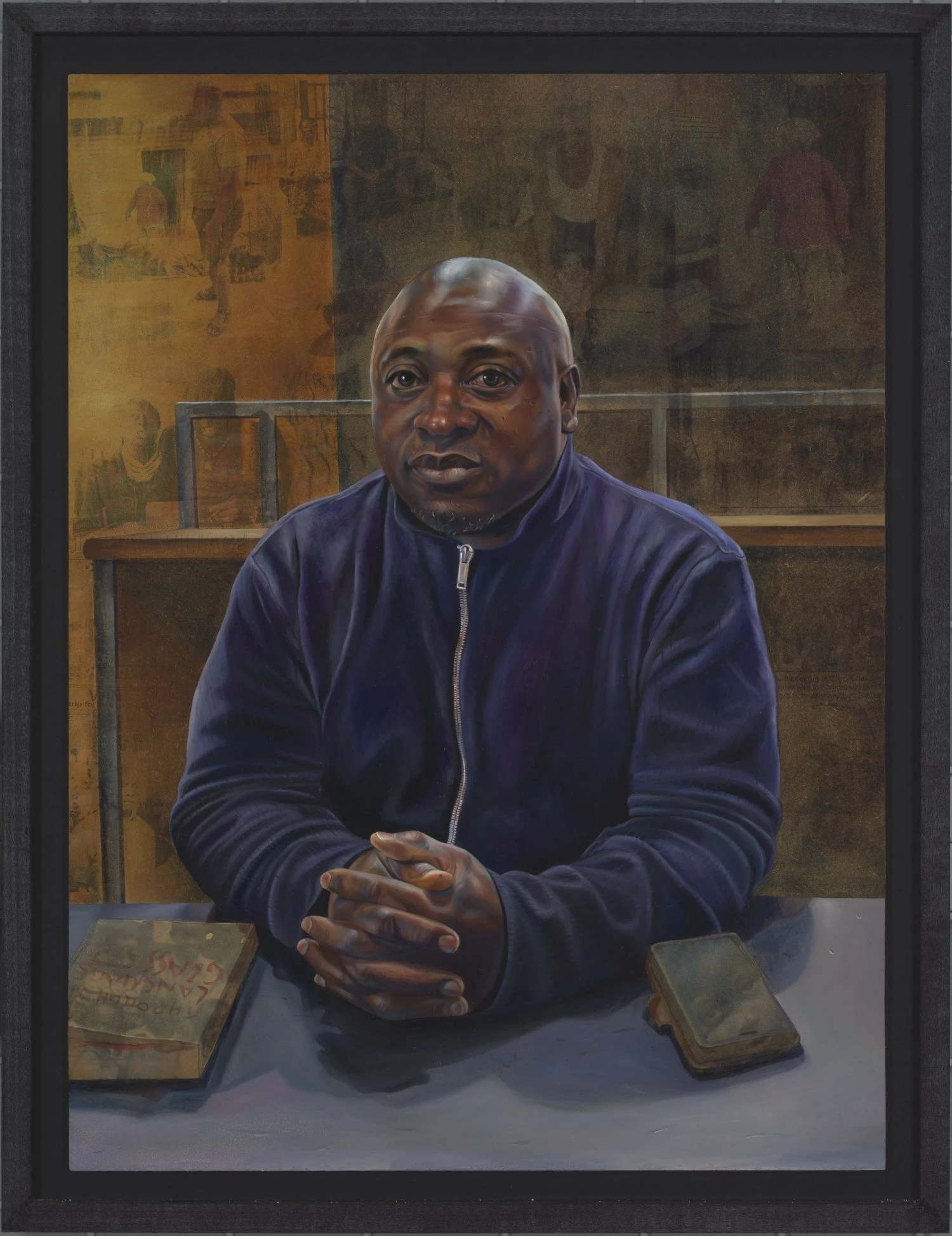

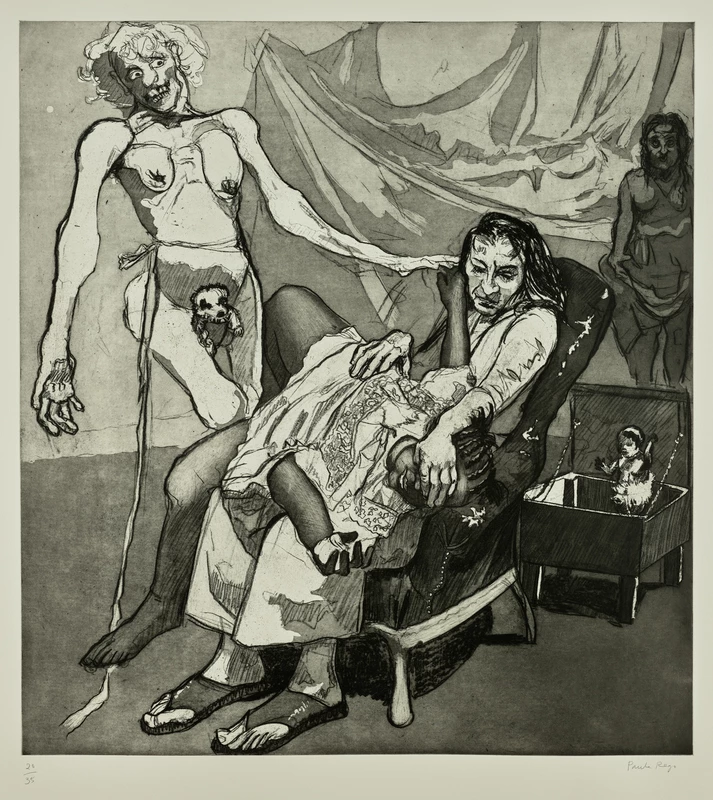

The studio in which Paul Mpagi Sepuya constructs most of his photographs is also his dominant subject. From one work to the next, Sepuya layers new visual possibilities for representing the artist studio’s capacity to be an incubator for different kinds of intimacies between bodies, most often those of his (usually male, Black, unclothed) lovers, comrades and co-conspirators. In his photographs’ intricately arranged choreographies of bodies, mirrors and machines, the studio becomes a place of softness and tactility, a place where queer and artistic networks play out in varying aesthetically suggestive ways, driven by a sense of both strength in collectivity and an ambivalent relationship to the human body’s status alongside the non-human. His medium, the people he portrays, the spaces they occupy and the technology used to render them are one and the same, and his oeuvre has created its own distinctively self-reflexive mode of contemporary portraiture.

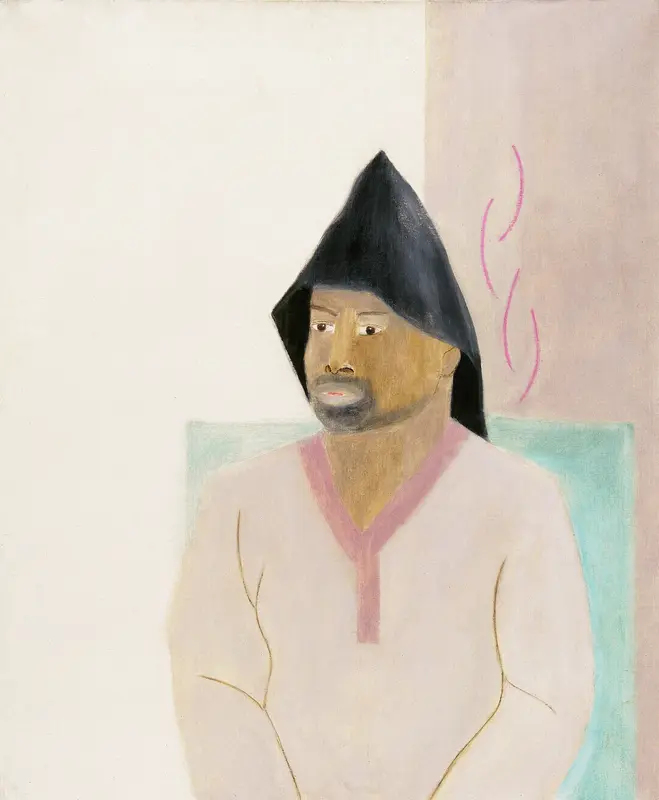

Sepuya’s Studio (0X5A4983), in the Amgueddfa Cymru collection, does image bodies, but neither those bodies nor the space they occupy is the photographer's protagonist per se. That position is occupied by the camera itself. Pitch black and centred just-so, the camera asserts its strength and influence, demanding its looker meet its gaze head-on. In emphasising the instrument of photography itself as a privileged subject within the frame, Sepuya suggests the artificiality of a photograph’s construction, and the act of capturing a moment is exposed as an act of performance. Whereas mirrors, and the bodies reflected in them, recur throughout Sepuya’s work, here is the self-questioning impulse of his photographic portraiture pushed to its limit: Who or what is the subject here? Who or what is the artist? And where do we fit in?

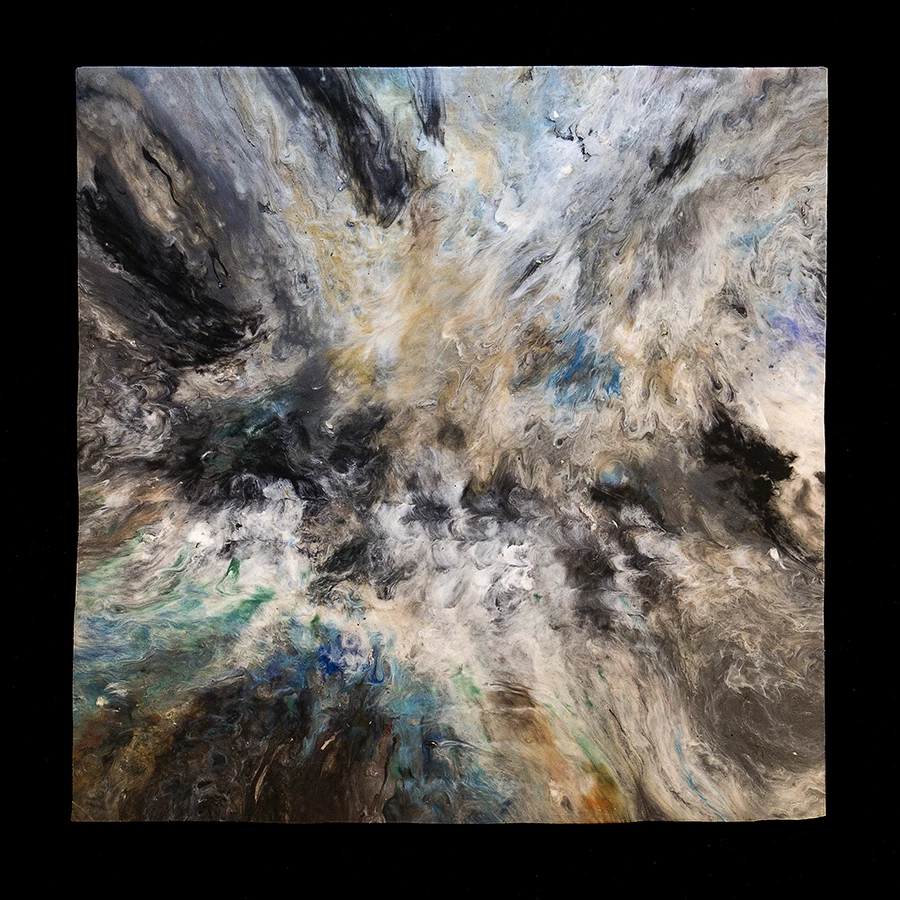

In his more well-known images, the studio is a place of light and of play. In more recent works, the sense of white-walled idyll is usurped by images dominated by black. The interplay of light and dark, a longstanding motif, is increasingly foregrounded. (The artist’s most recent solo show at his Los Angeles gallery, Vielmetter, was in fact titled Daylight Studio/Dark Room Studio.) Bodies are depicted as increasingly fragmented, cut up, abstracted. Sepuya’s specific darkness connotes not ‘darkness’ but possibility, escape. What might bodies, imaged in the dark, become?

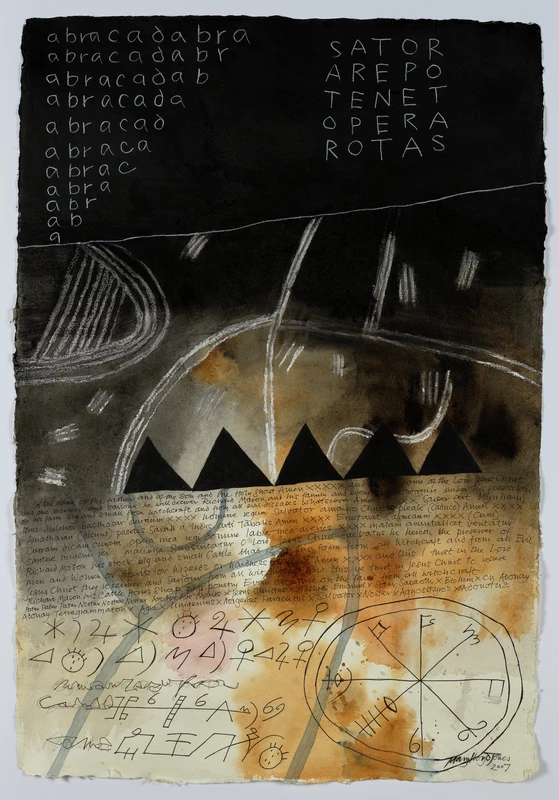

A darkroom is a room for processing light-sensitive photographic materials. Darkroom, Dark Room, The Darkroom or The Dark Room may also refer to: Dark room (sexuality), a darkened room, sometimes located in a nightclub, gay bathhouse or sex club, where sexual activity can take place. All pages with titles containing dark room. All pages with titles containing darkroom. Black room (disambiguation). Dark (disambiguation). Room (disambiguation).

Speaking of escape. Every time I see a Paul Mpagi Sepuya image I find myself transported, though not to the spaces depicted in his work but to a specific time and place in my own life. The month of my first visit to New York City when I was twenty-two, which was also my first time leaving Europe, Sepuya was the artist on the cover of Artforum. There is something about visiting a new city, especially one so hyper-familiar from books, films, TV and social media, which heightens one’s awareness of the precise historical moment being occupied. It was also, incidentally, the month the UK was due to formally leave the European Union. I’d just been offered my first art-adjacent job, an internship at a photography festival, having finished my studies a few months earlier. It was a time and it was a place, I was in New York City, Paul Mpagi Sepuya was on the cover of Artforum. Things were happening, and I felt it all with a desperate intensity.

I was in New York on a British Council bursary, as my first ever ostensible “work” trip, hardly believing this was real life but doing a pretty good job of faking it. Occasioning that Artforum cover was Sepuya’s exhibition The Conditions at Team in SoHo, which I remember vividly. Though Sepuya’s photos stop just short of outright titillation, something about viewing them grouped together in real life, as part of an audience, has the effect of emphasising their latent eroticism. We know that portraiture, a medium spanning as many technologies and eras as the notion of art itself, is uniquely attuned to an erotics of looking. To frame, to set up, to capture: a vocabulary loaded with ambiguous associations. The intensity of that experience felt rare; the whole exhibition felt alive, like it was talking back to me; whispering in my ear; teasing.

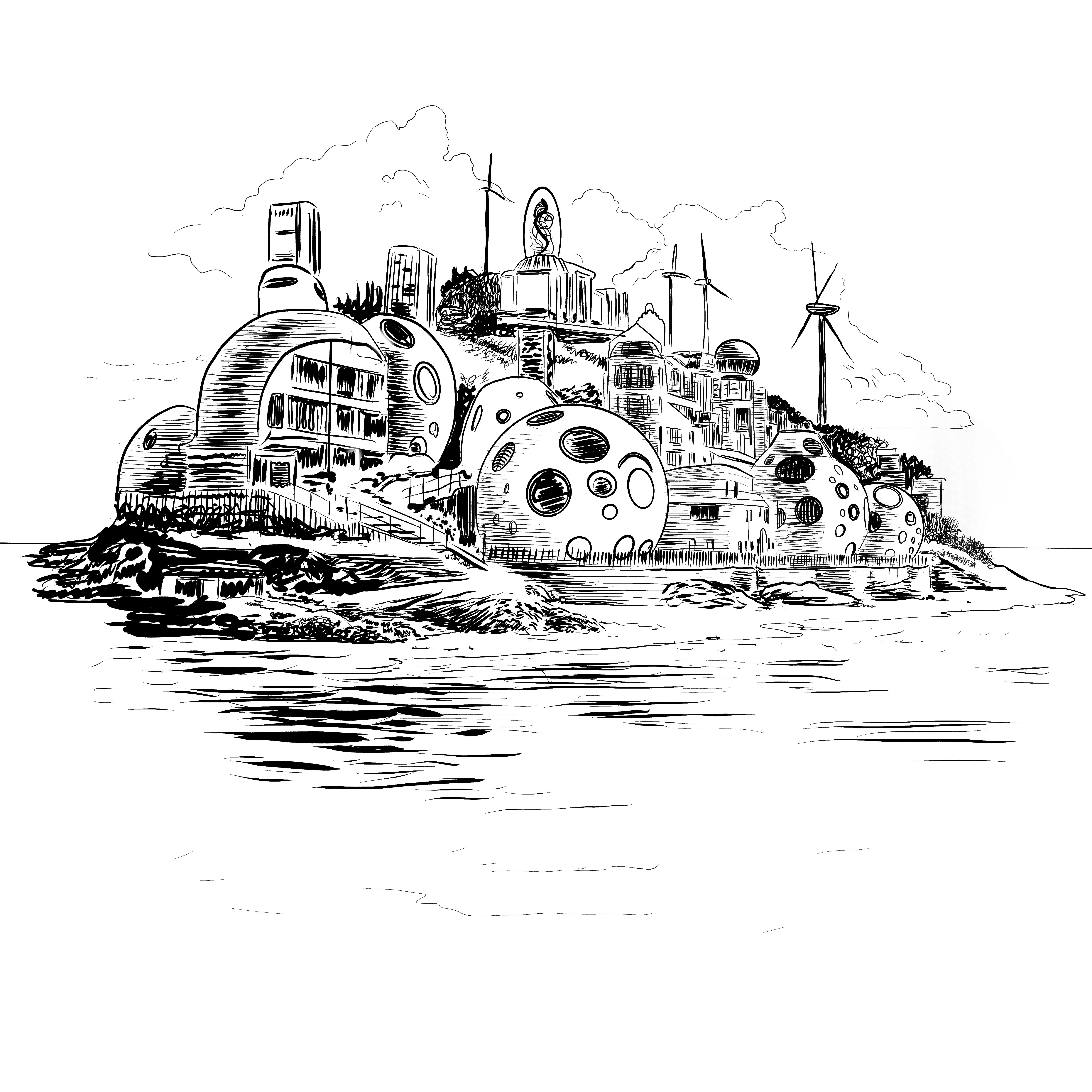

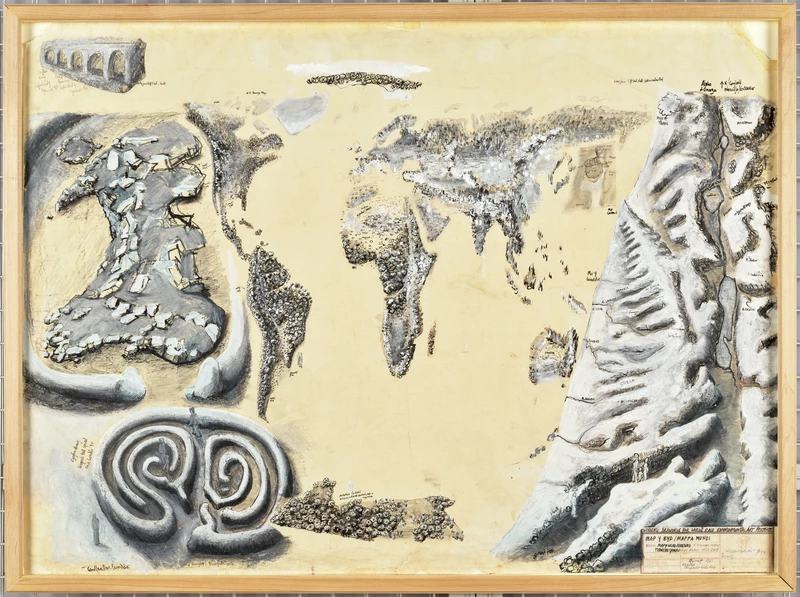

Being in new cities alone cannot help but conjure comparisons to the act of cruising; it’s an association so frequently made as to be a cliché of gay writing, but it’s particularly associated in my mind with New York. You’re made hyper-aware of the movement of strangers’ bodies among each other, and each glance met might open up a whole world of possibility. The same day that I saw The Conditions I saw the New York iteration of Cruising Pavilion, a curatorial project exploring associations between gay sex and architecture (and, implicitly, exhibition-making). Its press materials describe New York as “the ‘Teatro Olimpico’ of architecture’s sexual experiments,” emphasising both its rich history of liberatory spaces for gay/queer/trans discovery and experimentation, and the city’s violent encroachment upon those spaces. “Following Charles Jencks’ definition of postmodern cities as machines for sustaining difference,” the curators write, “it appears that the relation between the metropolis and cruising is crucial for measuring its capacity to host and generate new ways of thinking, loving, living, belonging and allying.” Perhaps the act of looking at photographs of bodies, the act of traversing urban environments and the act of cruising itself are not so different from each other.

I never, until now, published anything about the trip or anything I saw there; that whole week exists only in memory, and only in mine. Ten months later, I saw some of the same Sepuya works in the context of his exhibition at London’s Modern Art; though I remember enjoying and appreciating that exhibition, my encounter was not as vivid. The works were the same, or similar, yet looking felt more ordinary there, the intensity of my subjective sense of being in a time and a place alongside these artworks somehow less potent.

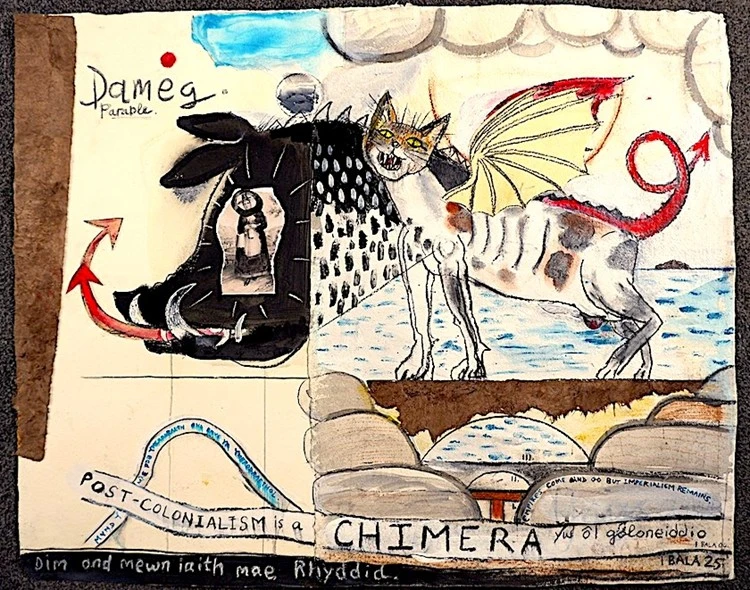

What defines one’s experiences of looking at art? And where does queerness — mine, an artist’s, a given built environment’s — come into it? These are questions with which I was occupied during the development of the ‘queer looking’ issue of Cynfas for Amgueddfa Cymru, which I guest-edited mid-pandemic. Seeking to think beyond the straightjacket of ‘representation’-dominated approaches to queer artistic production, I worked with the commissioned artists and editorial team to foreground the position of the ‘queer’ viewer, to see how works in Amgueddfa Cymru’s collection (and perhaps even the notion of a museum collection itself) might be problematised or enriched by being contextualised through the subjective positionalities of queer- and trans-identified artists and writers, each operating from their own unique aesthetic concerns, life experiences and research interests. The representation of the body in/as art became, perhaps predictably, a recurring theme. (The development of the issue was well underway around the time Studio (0X5A4983) was formally acquired by the museum; I wonder if we created a follow-up today what kinds of inquiries Sepuya’s photograph would provoke.)

The questions linger. What do we talk about when we talk about artists’ portrayals of the human body? What does it mean to stop and look at framed bodies with sensitivity and lucidity? How do we ensure we continually refresh our ways of talking about artistic production defined by a queer-oriented perspective? Like the lens of a camera meeting a queer looker’s eye, or a glance met in a darkened room, there is no straight answer to these questions; only invitations. To feel more intensely, and to discover more directions from which to look.

Dylan Huw is a writer working across disciplines and languages, often with and alongside contemporary visual artists. His critical writing appears in Artforum, e-flux, O’r Pedwar Gwynt and Art Monthly, and he was recently shortlisted for the International Award for Art Criticism (IAAC8). In 2022-3, Dylan’s practice is being supported as part of the Future Wales Fellowship by the Arts Council of Wales and Natural Resources Wales. Born in 1996 in Aberystwyth, he currently lives and works in Cardiff.