1.

2021. During lockdown, I dream the same dream every night, many nights in a row. In this dream, I'm in a garden, and the sun's light shines through thick foliage. It isn't my garden, but my friend's garden, who, in this dream, is a gardener. We roam the garden, and he brings me a cup of water, as if I'm another plant.

When I wake up, it feels as if a ghost has been in the room. I haven't seen my friends in months, only on the group chat, or a window into their lives through an Instagram post: a cake they've baked, a rainbow, a plant pot on a windowsill.

✻ ✻ ✻

As I browse the images in Amgueddfa Cymru's 'Collecting Covid: Wales 2020' collection, you notice that many of the images are taken in gardens. Like many of the other images in the collection, there are no people in these images. Only their presence – they are gardens after all, spaces created and designed by human hands.

I find two specific images that remind me of my dream. The garden in the first image shows evidence of careful tending, raised walls, pots filled with soil, plants planted. But we can also see rest – a bench has been placed to relax, and weeds grow in the bed.

In the other image, a green space has been transformed into a shrine, with coloured stones as offerings at the base of a tree, and colourful hearts hanging from the branches.

I imagine the people who spend time in these green spaces, tending and resting. What was there when they started? A concrete slab? A forgotten corner? What inspired them to create something beautiful? How did they choose the plants? Was the idea fully formed, or did it develop organically? Is their vision complete, or do they still see work that needs to be done, still imagining what that small corner could be after a 'better spring next year' or an 'afternoon of weeding' or just 'one more plant'.

When I wake up, it feels as if a ghost has been in the room.

✻ ✻ ✻

Another thing about lockdown was that I slept, a lot. More than usual. Time was suddenly more stagnant than linear. Something lukewarm, unmoving. Days without flow and nothing to drive you through the hours. Stagnant.

I found myself waking up later, going to bed earlier, and taking a nap mid-afternoon. One afternoon I fall asleep under a tree in the garden. When I wake up, the branches are full of noise. In the tree is a Blue Tit, and a family of fat little chicks following her clumsily from branch to branch. The Tit leaps between the branches scratching for bugs in the bark, feeding her chicks one by one, as they tentatively test their wings.

They pay me very little attention, and the mother flies so low above my nose that I feel the gust of air from her wings. I start bawling crying, red and ugly, like a balloon releasing all its air. I feel so, so, lonely.

✻ ✻ ✻

In lockdown, like every other period, gardens were a place to contemplate, pray, exercise – a space of ritual and healing. To those with access, of course. In Britain, 1 in 8 households don't have access to a garden. The figure is much higher for people of colour, specifically Black people. In England, only around 60% of Black people have a garden, compared to nearly 90% of white people. In Cardiff, 54% of homes in Butetown don't have a garden, compared to Pontcanna's 8%.

The housing crisis is also a garden crisis, a green space crisis, a climate crisis, a class and capitalism crisis. It is an international crisis that manifests itself differently in every community. In north and west Wales it takes the form of a second home and AirBnB crisis, and a language crisis. In Cardiff it is a gentrification crisis, of over- or mis-development, as well as a racial and white supremacist crisis.

Who can afford to dream in gardens?

✻ ✻ ✻

When I think about Covid gardens, and how so many people were turning to plants and gardens, some for the first time, I think about Samantha Walton's book, Everybody Needs Beauty. In this book she ponders what's described as 'nature cure', or the idea that nature heals. It seems obvious – of course contact with nature is healthy, and brings solace. Isn't people's reaction during lockdown undoubted proof of this, that so many of us instinctively turned to gardens and green spaces during a time of crisis, to commune with nature?

It seems such a simple and obvious concept, but Walton complicates the idea by asking us to consider what nature is, and other connected questions: who has access to 'nature' and 'green spaces', who is selling, marketing and profiting? Walton tries to question some of our preconceptions about the nature of nature, where it is found, and the practical implications on our health services of unquestioning dependence on the power of 'nature' to heal. As Walton states, 'plants aren’t substitutes for a fairer society’ (p. 122). But for those with access to a garden, that green space offers a therapeutic space where simple, repetitive tasks can be a form of meditation and mindfulness; a means to connect with a world that transcends the human; a sense of purpose; and in its simplest form, access to a beautiful space, and sometimes that's enough.

A similar instinct may be responsible for the proliferation of houseplants, especially among those who have less access to green spaces and the outdoors. It's a cliché by now to refer to the generation born after 1980, and their inability to buy homes, and their penchant for avocados. But there is truth in the cliché, and it's not unrelated that this is the generation most connected with the popularity of the houseplant. And it appears that popularity soared again during the pandemic, with everybody stuck indoors. It's easy to understand the obsession. The need for something beautiful, beyond the self, something to channel our loving energy, to care for, to distract us, to ground us, but something also easy to pack into the back of a van or car boot when the time comes to move on, again.

It's easy to understand the dream, and marketing companies, gardening centres and online influencers have successfully co-opted the dream for their own marketing ends. And they've gone for it in a big way. The houseplant business is a multi-billion-dollar industry that's still growing. They all sell their own versions of the garden dream, embodying the ideal created in a gallery of curated images. 'With this collection of tropical plants you too can have whiter teeth, better diet, more sunshine will somehow pierce through the windows of your dark flat, you will succeed at work and you will make friends. All for a reasonable price, and free postage...'

In the world of influencers and advertisers, they aren't selling a pothos or snake plant, but a dream connected to the plant (that inflates its worth). The plant can imply that the buyer is within touching distance of that dream, without doing anything to address the forces and systems that keep the majority from a dream of secure and settled homes.

The garden cannot replace a health service or a just housing market. And as with 'nature cure' in general, it can be turned into a neat commodity – packaged, branded and priced.

‘When the nature cure is repackaged by business or hoarded as a charm for the privileged, its radical potential is dimmed, but perhaps not totally lost. The problem is, these wellness solutions tend to treat nature as a tool, instead of thinking about how eco-recovery might work both ways. But mutual care is intrinsic to the nature cure. Why shouldn’t we want to care for the forests, mountains and wetlands that we lobe, to understand their inner workings so that we can tend and protect them?’

(p. 266)

How would a different garden, or gardening technique, look? Garden dreams with a radical potential to topple oppressive systems?

My friend is a gardener. We roam the garden, and he brings me a cup of water, as if I'm another plant.

2.

2022. Another rough April, and I'm listing plants to send myself to sleep. Forsythia, Clematis, Calendula, Comfrey, Sweet Pea, Lupins. In my dreams, my hands are caked in soil, and I stand by a small table in the middle of the garden. The table is covered with pink, orange and blue petals. My friends are sitting around the garden in shaded alcoves, talking or resting. I am the gardener.

When I wake up, another storm whistles through the chimney stack and shakes the window panes.

✻ ✻ ✻

Time in the garden is cyclical. It lends itself to dreaming and idealizing, because there is no end point. The dream will never be realized, but neither does it have to end, and it is remade constantly through the seasons, ever changing.

I believe that's where the joy of gardening is for me. Not in the 'finished' garden, the completed work, because there is no such thing as a 'completed' garden. It is constantly in the process of being created, but also constantly exists in different forms. The February garden exists as weed-filled pots and wet soil. But through tending the soil and planting seeds on sunny windowsills a second version of the garden is created that is sometimes more alive in the mind than the real garden, a garden that may never be realized exactly as it was envisioned, but somehow real nonetheless.

I want to find a word that describes this ever-approaching, multi-versioned, never-ending. Broaching, emanating, ever-futuring?

✻ ✻ ✻

I have a cold, so I go to the Co-op (in my mask) for the type of medication my garden cannot offer: Ibuprofen and Lucozade. (There's plenty of folk remedies, but I believe as strongly in the power of Lucozade and grapes, since Nain used to swear by them, as I do in the power of Ibuprofen and throat syrup.)

On the way, I pass a plant-swap shelf, placed outside a house in town where anyone can leave budding plants or seeds, or take something for themselves.

That afternoon I return with small pots of the white poppy that I have no more room for. By the next morning, three of the five have vanished, and two dozen young tomatoes have appeared. I take one labelled 'rosella' and replant it in a bigger pot.

I study the handwriting on the label, trying to imagine the person who planted the seeds, nurtured the young plant, before passing it wordlessly to a stranger on the street. I feel a strange connection, though I have no idea who they were. I imagine who took the poppy plants, who's caring for them now.

✻ ✻ ✻

Some days later I go for a walk, attempting to slay the cold with fresh air. It's a wet morning, it's just stopped raining, and I wander towards the communal garden. It's not really a single communal garden, but a series of locations spread across the town. I reach the herb garden first and kneel to read the labels by the plants: oregano, thyme, lavender. Looking around me, I take a cutting or two of Sage, feeling somehow guilty, even though the garden is there for everybody's benefit. But it still feels like stealing. I head on towards the vegetable garden, the beds green with familiar and unfamiliar foliage. The pink and yellow chard has grown enormous, and with newfound boldness I grab a handful of foliage, and a few bunches of purslane with its round, leathery leaves. The last thing I take is a cutting or two of lemon balm, before heading home with my haul. I add to the stash with a few leaves of peppery nasturtium from my own garden, and the bottom of a bag of indeterminate leaves hiding in the fridge, and prepare a plate of green salad that feels like summer on a plate. I use the herbs to brew a tea (adding a spoonful of honey) and feel the care of the unknown grower who nurtured these plants, before offering them as a gift to whoever needed or wanted them.

The communal garden principle is fragile. Do not take more than you need, leave enough for the plant to survive and thrive, and for others to reap the benefits. Join in the work too if you can, but you don't have to.

How different this is to the early days of the pandemic, when fear and panic led to those with means overbuying and stockpiling bags of rice and pasta and toilet paper, leaving others with nothing. A time when there was, actually, enough for everybody if people took only what they needed and left the rest. An imagined shortage creating a real shortage.

The communal garden challenges basic preconceptions about human nature and market forces, suggesting there's ways of growing and caring that don't depend on greed and excess. Ways that depend not on the fear of shortage, but on a faith in the ever-futuring.

✻ ✻ ✻

In this dream, I'm in a garden, and the sun's light shines through thick foliage.

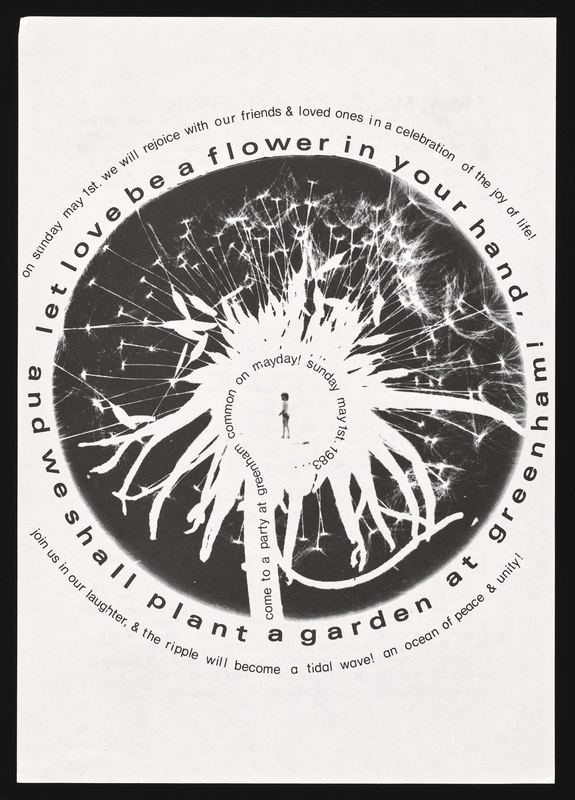

How do you tend a garden on a precipice? Many have succeeded. I think of Derek Jarman, and his Dungeness garden chronicled in Modern Nature. Jarman starts working on the garden soon after receiving a diagnosis that he's HIV positive. Prospect Cottage is a seaside cottage nestled, along with its garden, under Dungeness nuclear plant. Jarman gardens in the shadow of personal tragedy, community tragedy, and planetary tragedy. His garden, and the diary he kept when creating the garden, are two complex spaces. On one hand the garden is an escape, but the shadow of the nuclear plant and phone calls to friends on their deathbeds tie him to tragedies. And yet, it remains somehow a dreamspace. There's magic in his conjuring of a garden under such geographic conditions, but also in the diary's drifting between dream and memory and horticultural details. Back in the Museum's archive I find part of a flyer from the Greenham Common protests. In the centre of the black and white poster is a dandelion, surrounded by the words 'Let love be a flower in your hand, and we shall plant a garden at greenham!'.

Greenham Common Peace Camp was formed in 1981 by a group from Wales called 'Women for Life on Earth' to protest against the nuclear missiles kept in Greenham military base. The women stayed at Greenham until 2000 and, as foreseen by the advert, a garden was eventually planted there in memory of the camp.

The garden, like the symbol on the advert, is a clear contrast to the destruction of nuclear missiles. Not killing, but growing; not fighting, but caring. It's also a gendered space. The Peace Camp was famous for being a female space and a female protest, and many of the protestors' status as mothers and grandmothers was consciously weaponised in the fight against nuclear weapons. The women took pride in their roles as 'carers', a traditionally female gendered role that's therefore deemed inferior in a patriarchal system to 'male' roles, such as a soldier. By insisting the carer's role is equally valuable, if not more important than the soldier's, the women distorted patriarchal hierarchy and made the role of the carer open to anybody who identifies as a 'carer'.

The advert that calls for a garden to be built at Greenham also uses a weed to symbolise the garden, conjuring a wild, unmanageable space. Garden as revolution.

✻ ✻ ✻

In my dream, we all get to sleep in safe, green spaces. We can feel the sun on our skin, a gentle breeze, and lie in tall grass watching the flies climbing the long stalks, and over our arms, navigating our forest-haired forearms. We have time to doze and dream. We have safe homes to return to and time to do nothing. We have time to take care – of each other, of ourselves, of the human, and of those greater than that too.

References

- Modern Nature, Derek Jarman

- Everybody Needs Beauty, Samantha Walton

- One in eight British households has no garden