Organisations and individuals around the world have created huge catalogues of objects, art and information: museums, libraries, art collections, archives. A key part of this process is deciding what is or isn't worthy of keeping around to teach the next generation. After noticing the vast amount of truncheons within the National Museum of Wales' online collection, I started to ask why it’s important to collect and maintain these objects used to hurt and intimidate citizens? What does their existence teach us? I was inspired to create my own artefact that reflects the uncollected histories of the ways that laws are changed.

One particular truncheon struck me because of its connection to the Rebecca Riots, a West Wales protest against toll roads. During this protest men wore dresses and painted their faces to disguise themselves while they destroyed toll booths that were affecting their incomes. Their actions were illegal, but their violent protest is remembered because it led to the permanent removal of these toll gates. The truncheon has become a notable artefact because the police and the UK government intended to stop Welsh people changing their lives for the better. This double standard for acts of political violence is a recurring feature of the police.

Considering first how legal and illegal violence works, and with the recent movement of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (2021), it seems more pertinent than ever to be questioning how and why violence is used. Political violence is defined as both physical and psychological acts aimed at injuring or intimidating populations, and under the new bill this will be more harshly punished. Within the same bill, non-violent protest against government initiatives is restricted, even when the system harms their quality of life (and the quality of life of those who otherwise cannot advocate for themselves). Making peaceful protest illegal leaves no easy route to challenge the law. Legal change often takes generations to shift things far enough to affect individuals' lives, especially when those affected aren't represented in the House of Commons.

Within the UK a small selection of people decide the laws, and how they are enforced. The party with a majority is considered to have more power but the election results are based on First Past the Post rather than a system of equal representation. In addition, the people within the house do not fully represent the cultures and traditions of the nation. For instance 21% of the UK population is disabled, but less than 1% of MPs are disabled, they are underrepresented and their rights are not properly considered. 14% of the population is an ethnic minority group, but only 8% of MPs are from an ethnic minority background, and this becomes more pronounced when you consider intersectional identities. There are no transgender members of parliament, and we do not record the lives of non-binary or intersex people, so these statistics simply do not exist. Each person is influenced by their lives, culture and traditions. With limited representatives in our legal system, certain perspectives will never be heard and will never influence change. I believe that education and access to a wider and more open historical narrative will change the moral outlook of our nation and the way we distribute power.

Questions of legality often lead to decisions about what is or isn't appropriate history or culture, and what should or shouldn’t be protected. But who has the right to say what is or isn't worthy of remembering? Often those who need their culture protected do not have the time or resources to challenge their exclusion. We must show our support for others and make their needs clear. We can do this by using techniques like boycotting, petitions, strikes, picketing, and other methods, and if direct protest is illegal, the only method left is illegal protest. Either that or continue to suffer or act as a passive oppressor, maintaining the status quo for future generations.

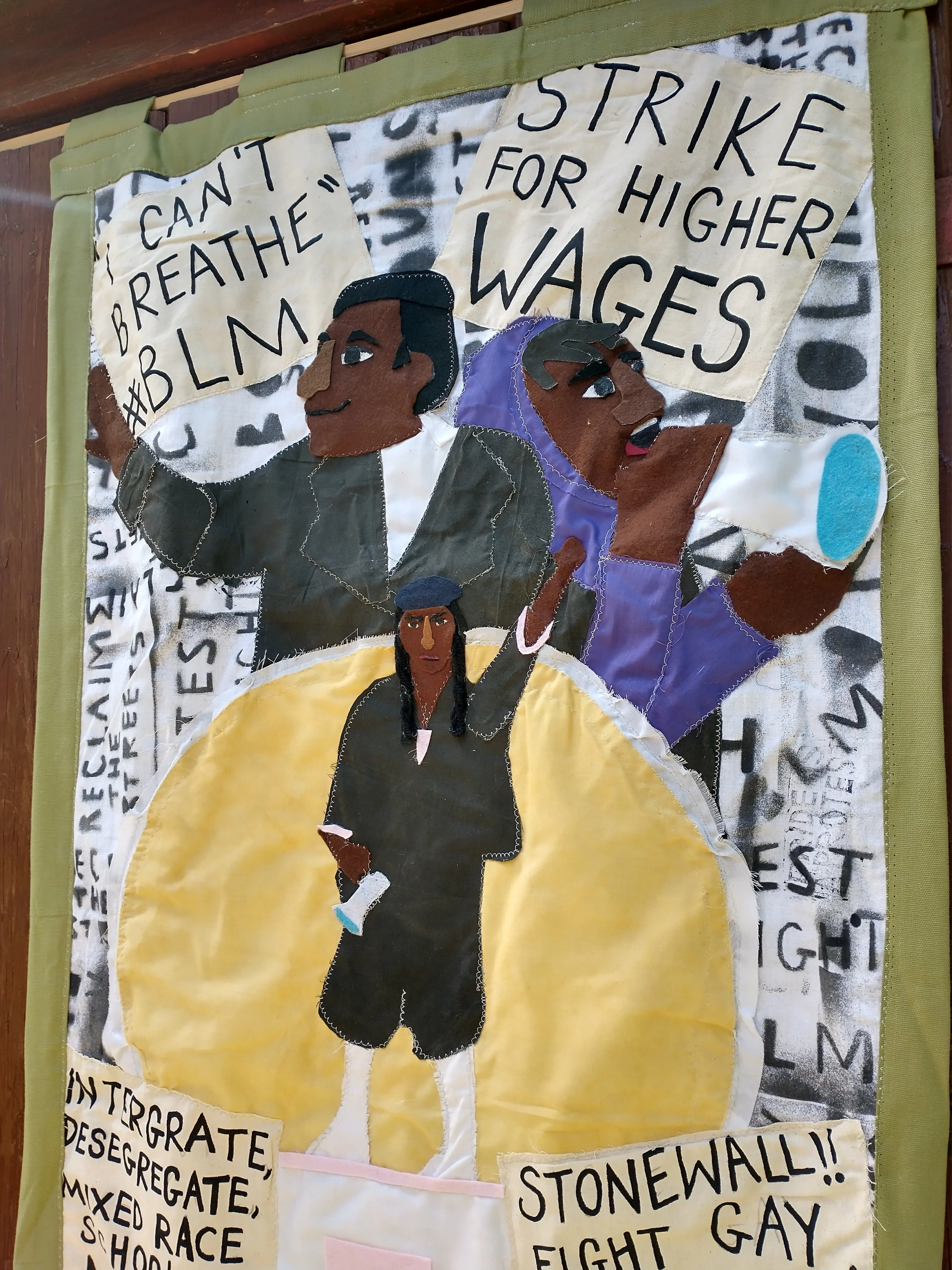

To celebrate the historic achievements of protest I have created this banner, in fabric and mixed media, to universalise social movements. There are many notable figures: top left is Martin Luther King Jr, top right John Boyega, bottom middle is Greta Thunberg, and above her are Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. The frame colours were chosen to create a green and purple combination with the clothing to reflect the suffragette movement. Transgender flags and their colours were added as highlights. The overall grey-purple-yellow combination inside the frame are the colours of the non-binary, asexual and intersex flags, which speak to the wider range of anti-sexism movements. The phrases on the plaques are not quotes, but were created using references from hundreds of riots and protests over the last 125 years, all highlighting the breadth of issues that have been tackled using protest. Each aspect of the piece represents a wider area of social history worth teaching, many of which saved lives.

We know the way in which the distribution of wealth and power often decides whose history is recorded. We cannot forget that it was less than a 100 years ago that we lost millions of minority people to the Nazi movement, as well as in priceless organisations like the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, the Bauhaus, and almost every important building in Warsaw. This period changed the way that many minorities have been socially classed ever since. Just as important is the history lost, stolen and appropriated through colonisation. We see this same erasure of Black peoples’ histories of enslavement and emancipation. And again, the AIDS crisis led to the loss of many people of diverse genders, sexes and sexualities because of social stigma around the illness. We see the erasure of individual freedoms of those imprisoned or in mental institutions, their right to vote, their autonomy removed, and the lasting effects after their release. We can all agree that it is wise to learn from past mistakes. How we share our history, what we celebrate, helps to form our cultures and traditions. What we memorialise is all we have to learn from.

The Black Lives Matter movement has raised many questions about the way we record history, and whose story is left unseen and uncelebrated. Without understanding the struggle of others we will never understand how to create a safe community, we will only be looking out for people similar to us. Every culture has events that shake the system. But it is our response that’s important: who we idolise, empower, how we rebuild, and react. How we record history next is up to us.

Artist's Statement

Working under an alter-ego, She Elloise, She creates artworks to highlight social structures with mixed media, such as ceramics, fabric, paint, collage and illustration.

She often works with self-portraiture and self-reflection. She often creates obtuse religious imagery that speaks to the nature of social structures and the mindset of the West, especially the UK. She focuses on subjects such as ableism, neurodivergence, wealth, diversity, gender, and sexuality, highlighting the roles of autonomy and power.

Insta: @she.elloise

Twitter: @SheElloise