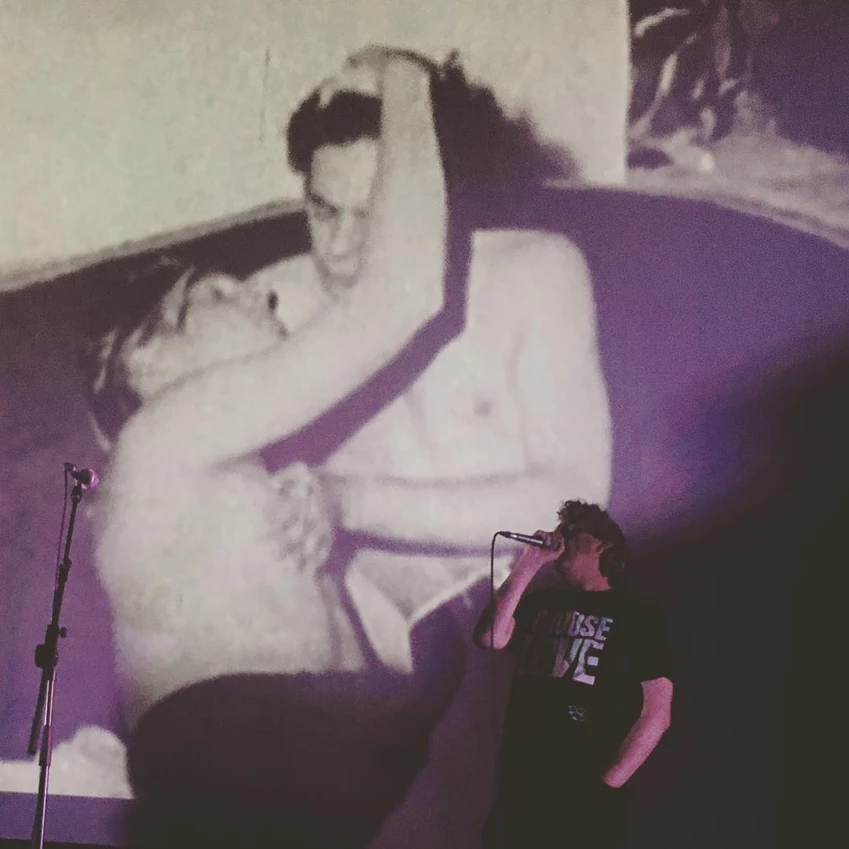

The synthesisers gurgle for the final few minutes yet the musicians are no longer on the stage. David R. Edwards has left the building (probably for another smoke break). The cinema audience is now totally absorbed by what had been projected before them for the past 50 minutes: an endless and hypnotic kiss in pristine black and white.

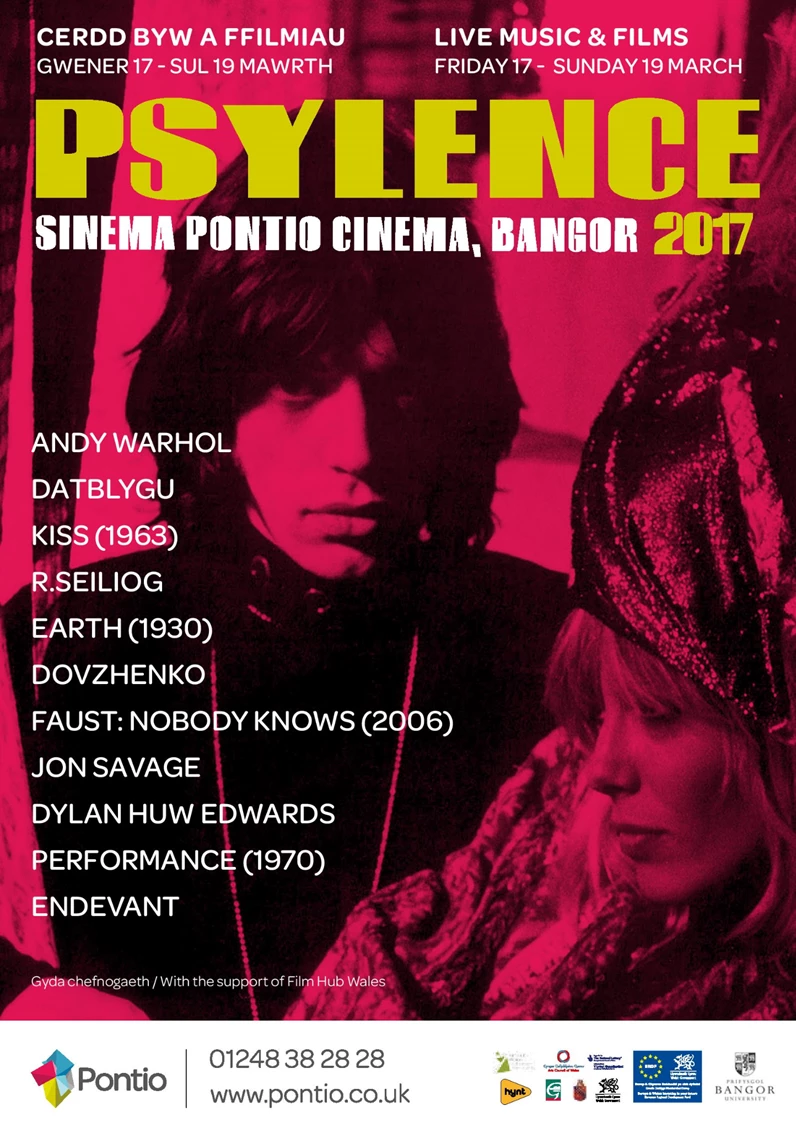

This was the night in March 2017 when Warhol’s Kiss came to a cinema in Bangor. Datblygu, the seminal Welsh-language post-punk band, played what their frontman promised to be their final performance. He kept to his word, though no one really believed it at the time. What I did know for certain was that what I had witnessed was performance art – nothing less – of pure and unparalleled delight.

Datblygu’s singer and lyricist David R. Edwards sadly passed away in June 2021 at the age of 56. Since they formed in 1982 his band’s efforts at creating a modern, alternative and unique sound within the Welsh-language music scene are completely peerless, while David’s influence within the Welsh cultural underground as a singer, lyricist, poet and cultural critic is immense.

My first encounter with Datblygu was suitably visual. Sometime around 2012, someone plastered old telephone boxes in Cardiff with posters of David’s profile with the slogan ‘BT BRITISH BASTARD TELECOM’ written underneath. The photograph used on the posters was the same as the cover photo of David’s autobiography Atgofion Hen Wanc (‘Old Wank Merchant’), featuring David as a young man: tousled hair, handsome and striking.

Shortly afterwards, in another unlikely act of situationism, I became further acquainted with the band at a cafe in Canton, owned by Pat Datblygu’s sister, which at the time had an exhibition on their wall commemorating Datblygu’s 30th year. I studied the band’s artwork and photographs on display, one of which included a very young Gruff Rhys watching them perform at the Eisteddfod. I was intrigued and bought a CD. My mam and sister were more interested in their coffee and waffles.

When I finally heard the music I discovered that David bellows those words from the poster at the beginning of their song ‘Rauschgiftsuchtige’. ‘Oh Laurie Anderson’ he croons, over and over as the song builds towards its raucous climax. For those listening to Datblygu without much grasp of the Welsh language, these are likely to be the only semblance of their lyrical output you’ll understand at first, save for the odd cry of ‘hello’, ‘yeah’ and ‘casserole’.

At Sinema Pontio in Bangor, however, the performance that night transcended language barriers and semantic understanding. Warhol’s visuals, 50 minutes of various couples, mixed races and genders, kissing for 3.5 minutes each. 3.5 minutes? An ideal length more or less for a decent pop song, and there were plenty of those too of course.

Speaking to Emyr Williams, the event’s organiser, and co-founder of Ankst records which released and reissued many of Datblygu’s albums, he explained to me his motivation for procuring this particular Warhol film. ‘It is one of his more honest and engaging films. He’s not a disinterested creator here – I imagine he was more involved with this film than some of the others he made. It’s beautiful in a very unique and simple way. It is a non-narrative but essentially it is also showing us the only human narrative that matters.’

This rotating cast of sensual portraits serve as the backdrop for a seamless medley of Datblygu songs. David is a looming yet kinetic presence on stage (when he’s not popping out the fire exit to smoke a rollie during instrumentals). Pat, all the while, coolly focussed and still. Gloomy, minimalist keyboards, David’s voice full-throated, more muscular-sounding than the young man on those old ’80s cassettes. Old favourites such as ‘Mynd’ and ‘Problem Yw Bywyd’ are sung assuredly, sans sneer, while Pat’s backing tracks sound surprisingly modern, remixed and reinterpreted; a testament to her musicianship.

In front of the crisp black and white upon the giant screen, both the music and film possess their own air of timelessness. It’s a powerful mix for the audience, the live and happening on stage, those intimate acts from 1963, the other-worldly and singular-sounding music, David’s anxious energy, all embrace one another like the figures oscillating on the screen.

In what I assumed was a nod to The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, the concerts in the Factory that the Velvet Underground performed in front of Warhol’s visuals, Emyr challenges. ‘I can't imagine Datblygu being in any way a copy of something else – what you were going to get on the night would be 100% Datblygu nobody else.’

What I got on the night has stayed with me like few other performances. No more so than the image of David and Pat, themselves former lovers and, as recent tributes and obituaries for David have described, ‘musical soul mates’, standing together on stage, Warhol’s cast kissing in the gulf between them.

In Emyr’s view ‘Datblygu were the equals of Warhol and as such the kiss would be an artistic one between Datblygu and Warhol as much as being something between Dave and Pat.’ While he’s reluctant to make Exploding Plastic Inevitable comparisons, there is plenty of common ground between the Velvet Underground and Datblygu. I would go as far to call Datblygu a Welsh Velvet Underground, had the Velvet Underground not already had a Welsh member. There is, however, something more to be said about this within the context of Welsh-language music.

Before Datblygu formed in the early ’80s, Welsh-language rock music for the most part had carried on as if their Velvet Underground had never formed. There was folk, radio rock, ‘grwpiau hwyl’ (fun groups) as David put it disparagingly in an interview with HTV as a sixth-former. Then there was Datblygu, inspired if not directly by The Velvets, then certainly indirectly by their art-rock disciples The Fall. There’s the oft-repeated Brian Eno quote about how everyone who bought a Velvet Underground record in the ’60s went out and formed a band. Whereas the likes of Super Furry Animals, Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci and Cate Le Bon all credit their inspiration and experimental leanings in part to Datbylgu.

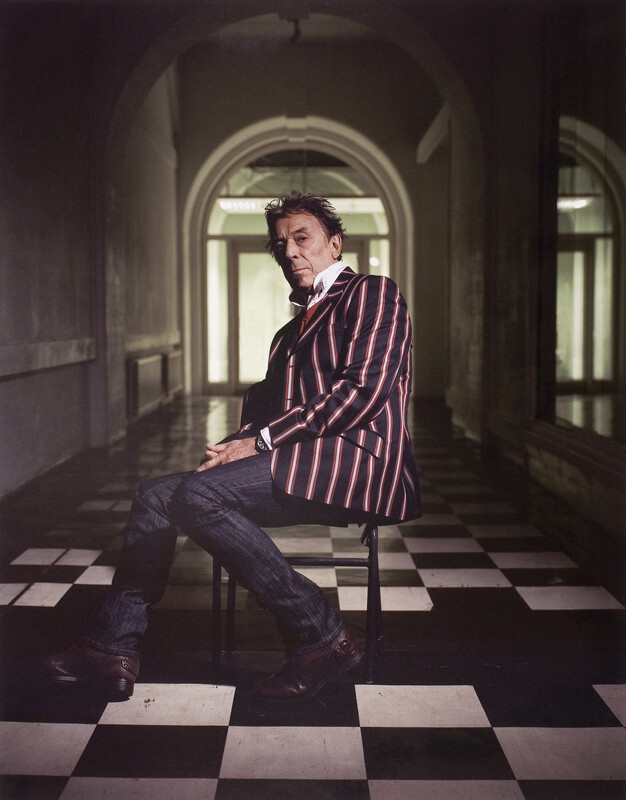

In our discussion Emyr refers to John Cale as the gateway to his Warhol obsession; the unlikely story of how Cale, the prodigious musician, went from rural and socially conservative Carmarthenshire to the centre of avant-garde art and rock and roll in New York City has long intrigued me. The night Warhol came to Bangor struck me with a feeling of circularity. When Kiss was first shown in galleries in New York in the ’60s, an accompanying live soundtrack was sometimes provided by La Monte Young, who famously introduced Cale to the practice and concept of ‘drone’, the sound which defined the music of The Velvet Underground.

The marriage of art and music is intrinsic in Cale’s career. The image of Warhol’s Banana is inseparable from the VU’s excoriating sound, whereas the genre Art Rock was basically coined to categorise it. The most complete attempt of Cale’s audio-visual pursuits sits in an elaborate black box – including laser-cut USB holders and detailed instructions provided by the artist – in the possession of our National Museum.

Dyddiau Du/Dark Days, a five-screen installation created by Cale in 2009, is an audio-visual piece which represented Wales in the Venice Biennale the same year. Described at the time as ‘a reflection of Cale’s personal relationship with Wales, the Welsh language and the wider issue of communication.’ The film contains footage of Cale’s unoccupied childhood home in Garnant, Carmarthenshire, a scene involving him walking up a slate heap in a quarry in Snowdonia pleading innocence to his mother – ‘I didn’t do anything’ – the loose slate perilous and jangling under his feet, as well as an even more arresting sequence involving Cale being tortured by waterboarding, accompanied by the sounds of a rugby crowd belting out ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’. This final haunting image sounds like it could have come straight from the Datblygu songbook.

Cale has talked openly in interviews and his autobiography What’s Welsh for Zen? about the oppressiveness and trauma he encountered growing up in Wales, and this work undoubtedly reflects and addresses that. It may come as a surprise to the casual listener of John Cale, where Wales acts as a place of nostalgia in the likes of his Dylan Thomas-inspired song ‘A Child’s Christmas in Wales’.

While discussing Dyddiau Du in the Guardian he describes Wales in the early ’60s as somewhere you had to leave: ‘The place scared me; it was going nowhere.’ In the Datblygu song ‘Gwlad Ar Fy Nghefn’, (‘Land On My Back’) David sings

‘Byw yng Nghymru

’R un peth â syllu ar y paent yn sychu,

Ar y gwair yn tyfu lan

Tyfwch lan.’‘Living in Wales

Is the same as watching the paint dry

And the grass grow

Grow up’

By way of his vast talent and vision, John Cale left Wales, at first on a scholarship to Goldsmiths, where Fluxus nurtured his interest in experimentation, and then to New York, eventually losing his ability to speak Welsh. Twenty years later the schoolboy David Rupert Edwards decides to dig his heels in and modernise Welsh music and culture with the Welsh language as his vehicle. Touching on this Emyr elaborates, ’Dave always had issues with the New York Avant Garde – “Yankee gyda acne, mewn crys T” [“yankee with acne in a T shirt”] – and he had said many times that you could be just as avant-garde in Aberteifi as you could in New York City. So I think he enjoyed the concept of sharing the stage with Warhol.’

On their song ‘Smalltown’ from their biographical Warhol album Songs for Drella Lou Reed and John Cale sing from the perspective of Andy Warhol:

‘When you’re growing up in a small town

You know that you'll grow down in a small town

There’s only one good use for a small town

You hate it – and you know you’ll have to leave’

While Cale and Warhol swapped Garnant and Pittsburgh for New York, David moved from Cardigan to Aberystwyth, Bangor to Carmarthen, and even as he struggled with severe mental health problems he remained committed to a small-town life and an artistic expression that was original and true.

David, of course, was abetted with a clearer idea of how he could be artistically radical in Wales than John Cale was in the ’60s. He was inspired by post-punk and the music he discovered listening to John Peel which in itself arguably owed heavily to John Cale. Still, I love thinking about the wildly brilliant and different lives the two men lived. David, the travelphobe, who created a counter-culture within a minority one while still in secondary school. Cale, the classically trained scholar who crossed the Atlantic and changed music forever.

I marvel at how unlikely it all seems. Yet these cross-pollinations of unlikelihoods are everywhere to be found in art and music. They’re kept in temperature-controlled rooms in our museums, postered on our streets, there to be discovered on walls in cafés, our pubs and independent cinemas. How unlikely it seems that Warhol came to Bangor or that there will be someone who pairs these rarities together to create something new.

In the promotional material of the Datblygu concert, and when selling the idea to the Warhol Museum, Emyr used the quote from the Factory ‘superstar’ Ultra Violet about the fact that Andy encouraged such events back in the day: ‘Andy blows up an idea bigger, better and louder by having the musicians play live on stage while the movie is being shown. When you come out of the movie house, your head echoes for days and you have trouble hearing anything but an ambulance.’

Art and music echo endlessly. Forever the two feed into each other, like a looping drone or, better still, a continuous kiss.