I vividly remember wearing my mother’s clothes when I was five years old. Frolicking around the house in them must have felt freeing, like Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music. Red lips, blue eye shadow, a frilly skirt decorated with – I think – images of petunias and roses on mustard-coloured fabric, a straw hat, a blouse. I know this because there was a photograph of me wearing these things, where I’m sitting at the top of the stairs. But in my early adulthood, I found the photo and ripped it up. It was never to be seen again, but I remember it.

Gofynais i mam os mae’n cofio fo. Mi oedd hi’n cofio fo’n iawn. Wnaeth hi feddwl yn galed lle mae’r llun wedi mynd, tan imi gyfadda bod fi wedi ddinistro fo.

I’m always surprised by my memory of this image, and how to this day I feel saddened by the fact that it is not a thing that exists in the world anymore. I think about it a lot. A mere photograph taken by, I assume, my mum, holds a force so powerful and invisible that I cycle through an array of feelings — shame, sadness, glee, pride — but ultimately I remain ashamed. Why is this? Why does this image still possess me, despite it having been disintegrated in a dump somewhere and becoming waste years ago?

How did I know at that time that the photograph needed to be gone?

Tyfais i fyny ar Ynys Mon mewn pentref bach iawn. Roeddwn i’n byw’n ofnadwy o agos i draeth, a roeddwn i’n medru gweld o tu allan o ffenast fy ystafell wely. Mae’r gallu i anadlu mewn lle gwledig yn neud i chdi gwerthfawrogi o’n fwy pan ti’n ei ddianc o am ddinas. Sydd yn beth amlwg i ddweud, ella, ond y peth cyntaf dwi’n meddwl amdan pan dwi’n trafeilio nol adra ydi’r ffordd mae’r aer yn teimlo ar fy nghroen.

The photograph was taken in my childhood home in Aberffraw. It’s where a large portion of my family grew up and continue to live. Anglesey is known as a setting for many mystical tales of Welsh folklore, rooted in the land, rugged coastlines, rocky coves and windswept moors. The legends that surround our land are drilled into us at school, where our imaginations about magic, spirits and creatures inhabiting where our homes reside give us a sense of pride. We can believe that where we live is magical, and that maybe said magic is something we could possess too. It could also just be gossip used to get carried away about the possibilities of what is invisible. As you can imagine, in small villages everyone knows each other and claims to know each other’s business. Who is who, where does this person live, what did they used to do, who are they related to, where do they work?

‘Lot o bobol dydan ni ddim yn nabod yn byw yn y pentref rwan,’ medda Nain.

To not know or fully understand something can be frightening. To me, it opens up the world to so many potential discoveries – about the self and others – that if we learned to look a little more, might be something we needed to see all along.

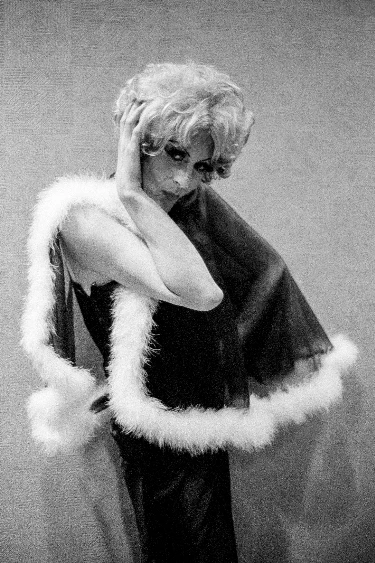

Looking through the Amgueddfa Cymru online collection, I was immediately drawn to the photography of David Hurn. Particularly to an image of three drag queens getting ready for a ball in London. Images like this one make it clear to me why metropolitan cities are an attractive pull for queer kids from rural places – like I was, when I left Aberffraw for London at age 19. The promise of the space, the community and the drama of the metropolitan.

I had only been to London once in my life when I was at art college, and I knew in my heart that it was where I needed to be at that time. It was a comfort in being myself that I hadn’t felt before. I guess being in the biggest city possible in the UK meant, covertly, that I could be anyone I wanted to be. Dress how I wanted to dress, go wherever, see whoever, ‘be myself.’ Or, perhaps, be ‘extra’ myself.

David Hurn, Getting ready to leave for a Gay Ball in Bayswater. London, England © David Hurn / MAGNUM Photos / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Images are divisive. They can hide truth, reveal something that was not known or even lie to you.

On March 30th, 2014, a blaze engulfed The Three Crowns, which had been the only gay bar in Bangor, the closest city to where I was raised. (It was the day after the UK Government passed the bill that allowed for same-sex marriage to be legalised.)

There were no reparations for this attack. An apparent ordeal between two business partners resulted in a whole building being set aflame, and the pub manager suffering severe injuries, despite the man accused allegedly starting several fires over the twelve months prior to this one in that area.

I had only been there once. My memory of that experience is murky because I was quite young, and drunk. I remember it felt small, which meant it filled with people very, very quickly. I remember a lot of glitter, red curtain draping, a place dense with atmosphere. Dense and warm from the amount of bodies that congregated together to disco music. In a decorative sense it wasn’t unusual from other bars I had been to, not really. The furniture was dark, varnished and sticky, just like the floor, strong pungent smells of lager stained air that extended to the toilets where that smell was mixed with the smell of piss. Glitter I think is the main material that I remember. A silvery, glittery wall in all its glamorous fakery. Glitter has its own language of campy decadence.

Again, camp is the attempt to do something extraordinary. But extraordinary in the sense, often, of being special, glamorous. (The curved line, the extravagant gesture.) Not extraordinary merely in the sense of effort.1

Roedd y gofod hwn yn teimlo’n wahanol.

That was the first gay bar I had entered in my whole life. To me it just felt different. There wasn’t anything out of the ordinary in its dressing, I suppose; perhaps the demographic, maybe the music.

I sense that spaces like these could legitimately be a place for self-discovery, safety, solidarity, promiscuity.

Then came the White Lion in 2015, hoping to reignite the unapologetic atmosphere that The Three Crowns created. Unfortunately, like so many queer spaces, it had to close recently due to financial pressures exacerbated by the pandemic. These aren’t the only places either in north Wales. In Penmaenmawr, a hotel named Pennant Hall that also housed a gay sauna has been sold off and will be demolished to build flats.

I’m glad to know that these spaces have existed in north Wales, but sad to not be able to enter them. I wish that I had known about them sooner.

To be queer for me is to embody resilience. You already know how to read the set of codes and signifiers that appeal to your desires. A queer focused archive is how vocabularies are refined, made clearer, to know that your eyes aren’t deceiving you. That you were right to read queerness into that object or image or space.

Photo courtesy of Keith Parry. 2011.

Mae fy rhieni yn ama bod nhw’n nabod pobol oedd yn arfer mynd i’r Three Crowns, ond tydi nhw ddim yn siwr.

Jyst gossip oedd o.

‘Be sydd yn digwydd yno?’ Fel petai pub hoyw yn drafnidiaeth i fyd gwahanol yn hytrach na pub arferol. I mi… dyna be mae pub hoyw yn wneud.

Siaradais gyda Robart Evans yn diweddar, sydd yn gyn-weithiwr a phreswylydd yn y Three Crowns a’r White Lion. Dywedon nhw oedd y bar angen bod yn rhywle i alluogi pobol i fod yn ‘extra’ nhw’n hunan. Sydd yn diddorol imi bod ni’n disgrifio ein hunan fel bod yn ‘extra’. Be di huna yn union? Ydio’n ‘extra’ ta ydio’n fod yn ‘dilys’ ti?

Mewn prosiect gafodd ei gomisiynu gan yr Eisteddfod yn diweddar, creuais fideo i ddogfenu’r sgwrs yma gyda Robart. Credaf bod hi’n bwysig i archifo straeon ac hanesion hunaniaeth a chymunedau cwiar ein ardaloedd gwledig, nid yn unig yn y mannau mwy metropolitian. Mae defnyddio hanesion llafar, lluniau a gwrthrychau yn ein gallugoi i agosau tuag at gofnodi bywydau LHDT+ fwy eang, yn enwedig yng Nghymru. Drwy gofnodi hanes y bobl gallwn ddysgu mwy am y cymunedau, eu gwleidyddiaeth nhw a’u dymuniadau a’r gyfer y dyfodol. Wrth wneud ymchwil i’r prosiect, ffeindiais luniau o’r bar drost blynyddoedd ar dudalen Facebook.

Closed doors, inconspicuous doors, doors hidden in plain sight. The unspoken is how we can conjure up possibilities and fantasies for ourselves.

Reaching for something through wanting. Not quite touching; unable to, not quite there. The hand, the arms, the whole body becomes an object for wanting. Thinking about the act of reaching out when I watch femme heroines on the screen and in images. Of course, I am unable to reach, but can only dream of doing so; there is a safety in that.

There’s something extraordinary about reading spaces and images in that way. The magic of making something come alive in your head, so when you draw something, or find something that makes something abundantly clear to you. That’s amazing to me.

The rukus! Archive that is available at the London Metropolitan Archive was created by artist Ajamu X and filmmaker Topher Campbell.2 It is Europe’s first living Black LGBT archive devoted to the heritage, culture and experiences of gay, lesbian and trans communities in the UK and on an international scale including Nigeria and New York. Its intellectual origins come from the work of Stuart Hall and British Cultural Studies more generally, and establishes a critical dialogue with mainstream heritage practices and dominant black and queer identity discourses.

As well as being an archive of objects and ephemera, they host exhibitions, talks, workshops and educational resources dedicated to the Black LGBT experience. I remember seeing some of the objects available at the archive (which was also my first visit to any archive). I was thrilled and surprised to see the different objects available. Selfie-esque photography, notes, promotional material, letters, minutes, diary entries and a comments book from an exhibition.

What could a queer archive in Wales be? Could it be artist-led? Who might contribute to it? Would it be open-source?

I would argue that it shouldn’t be bound to any rules or hierarchies. Perhaps the photographs by Keith Parry over the years spent at The Three Crowns should be there. How about the sign of the White Lion? Where will that go? Pennant Hall now exists as a set of TripAdvisor reviews and, after a bit of digging, you can find its old website archived – but only if you go looking.

Maybe that photograph of me as a child wearing my mother’s clothes could have been included, if it hadn’t been destroyed. Maybe my own testimony that it existed can be considered a piece of oral history, since I am writing about it right now, years later, and equating it to all my queer experiences. I talk about the pubs I have been to, I think about the photograph. I refer to other archives, I think about it. I sit in silence, I think about it. To see queer and memorize it provides an affirmation for who I am. For that moment I felt brave enough to expose my femininity to whoever is taking the photograph: why can’t I do it now? Maybe if I saw it again, exploring more forms of self-expression wouldn’t be a shameful dream anymore but an affirming reality.

Watercolour drawing of me in my mother’s clothes. Courtesy of the artist. 2021.

Owain McGilvary is a Welsh artist based between Glasgow and Anglesey working with moving image, collage and drawing. His work often brings together different forms of oral histories, personal anecdotes, queer theory, storytelling, gossip and archival research.

1↑ Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp (1964), p. 7

2↑ rukus! Archive on the London Metropolitan Archive website