Olivia Quail, Bryn

At first glance, the sculpture of miner Bryn appears incongruous. The old school Welsh collier attire, complete with caged canary and pickaxe in hand, doesn’t blend seamlessly with the figure’s punky t-shirt and red polka-dot neckerchief. But pam lai? Crafted by the gogledd Cymru mother of a LGSM activist around the time of Mathew Warchus’ BBC Films spectacle Pride, and donated to Amgueddfa Cymru the following year, Bryn embodies an unlikely alliance between seemingly contradicting paradigms of culture, history and place. Their gift to the future is the confirmation that queer potentiality is latent, omnipresent, and the horizon is an emergence of multiple possibilities. This movement of opening up into latent potential space in the quest for survival and liberation was also personified by Rebecca and her daughters, who led thousands of cross dressers from all over Cymru in rebellion against peasant poverty. These are two amongst many loci in the cartography of Welsh memory that make up an interlocking overlapping map of queer feeling and being that creates future possibility and expands the imagination for everyone, not only queer people, now as then. These events haven’t fully disappeared: they linger and create conduits for knowing and feeling other people and places.

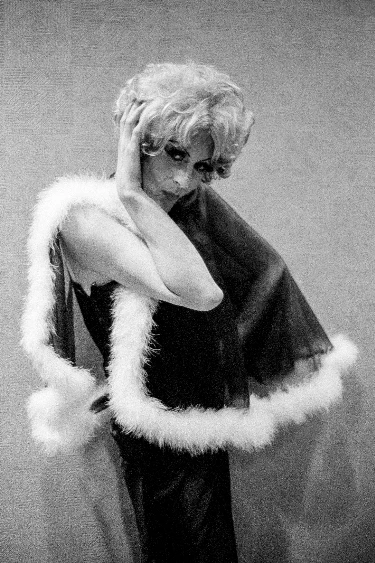

Wearing a wig may be a convenient disguise to operate under stealth and protect fugitive status, much like a badge or a hanky can be subtle signs worn discreetly to symbolise nonconformity. Such symbols can invite us away from a subject base understanding of queer being and towards a queer optic that isn’t anchored on any form of fixed identity; rather than the existence / presence of a queer something queering the space, what happens when we think with queerness simply being in place? The queer exists outside of a norm, or rather outside of the idea of a norm, that nonetheless creates an obstacle to being and belonging. A queer being is about intentionality and scope of movement rather than a singular focus. It allows for numberless relations between things and seeks to neutralise alienation and disrupt a baseline. Sustaining queer being requires an ongoing engagement with evolving political and sociological phenomena; we have to show how we want to be seen and how we want to be loved. Representation is sugar-like; it tastes good and brings comfort, whilst also being addictive and distracting. Liberation demands that the difficult, dark, odd, strange is allowed to remain, to exist beyond naming and to resist classification. The urge to ‘pass’ and to integrate can be violent when you don’t fully identify with what you are passing as / into, especially while queer being is constantly assured that it doesn’t belong and is out of place everywhere. This text is a non-linear narrative inquiry into queer being in writing. It acknowledges multiple departures, welcomes contradictions and invites questioning.

Break/down. Attempts to define queer being tend towards the singular. Perhaps it is more comfortable to conceive of queer in the singular, the odd number, devoid of ancestry or indigeneity. From here on Bryn becomes (oes, like the name) hill, slope – a collective pronoun, a diffuse shared presence rooted in / emerging from the love language of place. In this now, cultural transgression is a norm and everything is more than what you see. If we are either made invisible in order to fit in, or become hyper visible and stand out in sharp contrast, what is the cynefin of queerness? How can we be in agosatrwydd with place?

Approach belonging like a slow dance,

with deep care and devotion,

get better at listening,

and know that sometimes it will hurt…

Stop/Go. When you need to offset an abundance of bucolic feeling for landscape and the countryside, stop by Mynydd Parys for a sunset picnic – this place throws some serious shade on the vision of the rural idyll. The cracked open earth glows with multicoloured ore assemblages, nothing moves but the pools gurgling with gas exchange, nothing appears to live yet there are several species of rare bacteria and plants. This place is a house of commons for uncommon senses. Engaging peripheral vision here is to let in a cacophony of colour tones and light refractions, holding a soft focus you see only in granularity and texture. Climbing Bryn after Bryn of oxidised rock aggregations to meet with more bare sunken hollows made of weathered rock, and every rock a different combination of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, makes for a choreography of bewilderment. Picking up rocks to check for an optical dalliance, lining them up in colour scales, how many colours have appeared on the same rock? How many processes has this ancient being been shaped by in its becoming? This strange mountain speaks of ych-a-fi, desecration and loss, cause and effect and the offensives of extraction, but also of magic and mystery, and even empathy and care. The rapid response of the Parys Mine Company issuing their own coin to make sure workers got paid during a currency shortage is care; the long term build up of microscopic activity so effervescent now that it can be witnessed from satellites in space is magic. Who are the guides who move us through liminality, uncertainty, the space for un-making sense? The subconscious is a factory, not a theatre. “Hiraeth is in the sea and in the long mountain” and maybe also in the phantasms and ruins of Cymru’s industrial heritage, temples to extractivism scattered in remote peripheral places and hiding in plain sight, from Môn mam Cymru in the Gogledd to the once beating heart of the South Cymru coal field valleys.

Here/There. After the fifth and last time the planet turned into a snowball, the ice retreated and a rainforest ecology habitat was established that once stretched from Scotland to Portugal. Ceunant Llennyrch is a rare large remnant of Atlantic oak woodland in Meirionnydd brimming with scarce species of lichens, mosses and liverworts, lesser horseshoe bats, ravens, dippers and otters. This ravine gorge with a thick canopy of tree cover uninterrupted for 11,000 years is a marginal ecology, a vestigial organ persisting from another time, a survivor of the local timber and slate trade, and a reminder that apocalypses have already happened several times over. Meandering through the thresholds from woodland to riparian to heathland to grazing field and mossy rock nooks so cosy you want to give them a cwtsh, it seems obvious that straightness is a concept; nothing out here in this ancient world is visibly straight, the boundaries blur and the edges blend, morphing, shapeshifting. Until a thick horizontal grey line cuts across the field of vision: the border / bridge / dam containing the eastern edge of Llyn Trawsfynydd. Something in between, something far beyond, and behind it, a wall of murky deep choppy water. Thinking with the mind of a fish living in a flooded mountain stream turned nuclear plant cooling lake to whom time is a fluid, does change feel slow, incremental, iterative? A succession of concrete steps? A sudden rush? A vortex of inevitability? An artificial line drawn across the psychogeography of a complex landscape. The brutalism of the power plant is a mere mile away, yet is only visible when walking away from the dam in a southwesterly direction; the twin geometric cuboids are camouflaged behind the Bryn.

Attuning to traces in the physical and relational landscape means tuning into how everything is changing, mutating, responding, adapting. Folx like Bryn the miner are of the hills, valleys, coasts and mountains of Wales, generation after generation of politically fierce land-loving hard-working folx versed in the ancient language of the underground. Cloaked by the uniform of darkness, the full space where things become. The shapes of time are laid out bare there, inside the ground, in geological space-time, where we may meet with the dis-identification that can lead us to identify, and to shape the world in return. Bryn folx can also see in black and white where others may only see colour. There are cages even in wide open spaces. There are doors everywhere you look. There is a time when the words have ceased to have meaning and the feelings can speak at last.

(Bryn the miner is still there, one amongst many voices under the stewardship of Amgueddfa Cymru LGBT collection offering a gwahoddiad for surfacing queer sense-making. Dig in!)

fin Jordão (they/them) is a creative biologist and educator at the Centre for Alternative Technology, a disused quarry in Machynlleth.