How art makes us feel; better, worse? Sometimes feeling anything is enough.

"Phoebe Boswell’s pictures saved me, she draws how I’m feeling, it’s like she knows; she’d been where I was. It’s not good, being like that, like me I mean and I didn’t know how to tell anyone, not even my mum, especially not my mum be-cause she didn’t understand, she worried, and that made me worse. I found these drawings online. I saw the hurt in them, I didn’t like them but I did too, they said what I felt. I showed my mum, couldn’t tell her what was going in my head but the draw-ings talked for me." "What’s wrong with you" she said, "looking at pictures like that, they’re ugly." But she started to listen, to ask me questions. I told her, "See, I’m not the only one like this." When I saw Phoebe’s pictures I thought it’s like I’m not the only one, I’m not alone, I’m not a freak." Simone*

Phoebe Boswell: A to Z J is for Just Not Good Enough (Commissioned by INIVA)

It was Simone’s idea to record our conversations and her idea to let me write about how her in-volvement with art has supported her in recovery and management of her mental health. I mentor es-tablished and emerging artists and makers with experience of poor mental health. Most introductions are through contacts in arts, health or education circles, or we meet at workshops and arts events. Simone and I met at a Studio Upstairs exhibition, she told me about her ambition and challenges. We agreed to work together, setting a structure for a series of meetings, reviewing the relationship as we went along.

A constructive mentoring relationship enables a person to explore their own resources and ability, so they can find a way to where they want to be. Conversations are adult to adult, intent established at the beginning. It is important the mentee understands this is not a teaching, therapeutic, counselling or coaching relationship. I am a sounding board, to support the mentee to make their own, informed decisions.

Simone had severe, undiagnosed depression for most of her adolescent years. Struggling, she wouldn’t leave her room, missing school, isolated from family and friends, experiencing a dark, limited world through a screen, believing she had no future and no way out. When she discovered Phoebe Boswell’s drawings online, Simone found a language in art. She started to draw "At first I drew tiny im-ages in a secret notebook, tiny, little scribbles about dark thoughts and pictures no one would ever see." She said it helped her "getting these bad thoughts out of my head makes me feel better, I hide the book under my bed. I won’t look at it again until I need get rid of more thoughts."

Boswell’s tight graphite marks, the black and white images, became Simone's first visual language, and She started to express her own emotions and situation. For her, the flash of the red J for "Just not Good Enough" was the desperation Simone felt as she clung to life. Her response to Boswell's illustra-tion told Simone she was capable of feeling. Exploring Boswell’s drawings, wanting see things outside of herself, her room, her life. Simone observed people through her window. She started to draw on any paper she could find, making dense, black, obscured shapes of people she saw outside. She was too embarrassed to show anyone her work. Her confidence grew as familiar figures emerged from her scribbled lines. Simone bought a sketchbook, stopped destroying her drawings and started looking at other artists work online.

In 2018, Simone, with her mother, went to Autograph, the London gallery showing Boswell’s The Space Between Things. "It was mind-blowing just going out and being near people but when I was there, I looked beyond myself, I started to forget I was scared and useless. If she [Boswell] could see a way through the misery so would I, I think I started to heal then." Simone’s depression was differ-ent from Boswell’s physical trauma, but Simone felt this outward expression of another person’s life significantly affected her view of her own challenges

Simone and I had conversations about her work, carefully considering fear and failure. By this time, she was studying art full time but her depressive episodes were a barrier. Supported academically and by health professionals, she felt unable to plan or develop her studies and arts practice, could only see problems and felt everyone only saw her depression. Simone did not recognise how much change she had made in her own life.

Within the context of her mental health and depressive language, we explored how personal history and being well might influence Simone’s creative response. Inevitably, as art is about everything, our conversations were wide ranging. There may be unpredictable outcomes when artists introduce the personal into their work. Talking about her professional practice, Simone and I explored the process of concealing or revealing intimate information. How reduction or editing may conflict with authenticity and deciding when to step back. I was interested in her decisions concerning acknowledgment of per-sonal and creative difficulties making art, how she reflected this in her work. At each meeting we re-viewed the impact our conversations might have had on her art practice.

If this tentative process of discovery and iteration seems dry, it is not. There is laughter and light, often revelations are challenging, unexpected or I learn something new. No experience is the same, visual triggers may cause us to pause, turn away, consider, change a mark or change direction. None of the people I work with shy away from "difficult" but want, in different ways, to feel able to embrace the complexity of their feelings and create something from them, if only to leave these experiences behind. Episodes of ill health may pass or underlying, enduring conditions may be constant in a person’s life, affecting everything they do, see, think about. Simone’s depression returns but she says "Art is always there for me." Her mother, too, began to look at life differently, but this is about Simone.

Phoebe Boswell’s art was Simone’s catalyst for recovery. A difficult first encounter which made her feel. She researches representations of emotion through creativity and is interested in the expression of de-pression and anxiety in narrative painting. Now at college in Cardiff, Simone visits the National Muse-um of Wales collections "for a place of calm and inspiration."

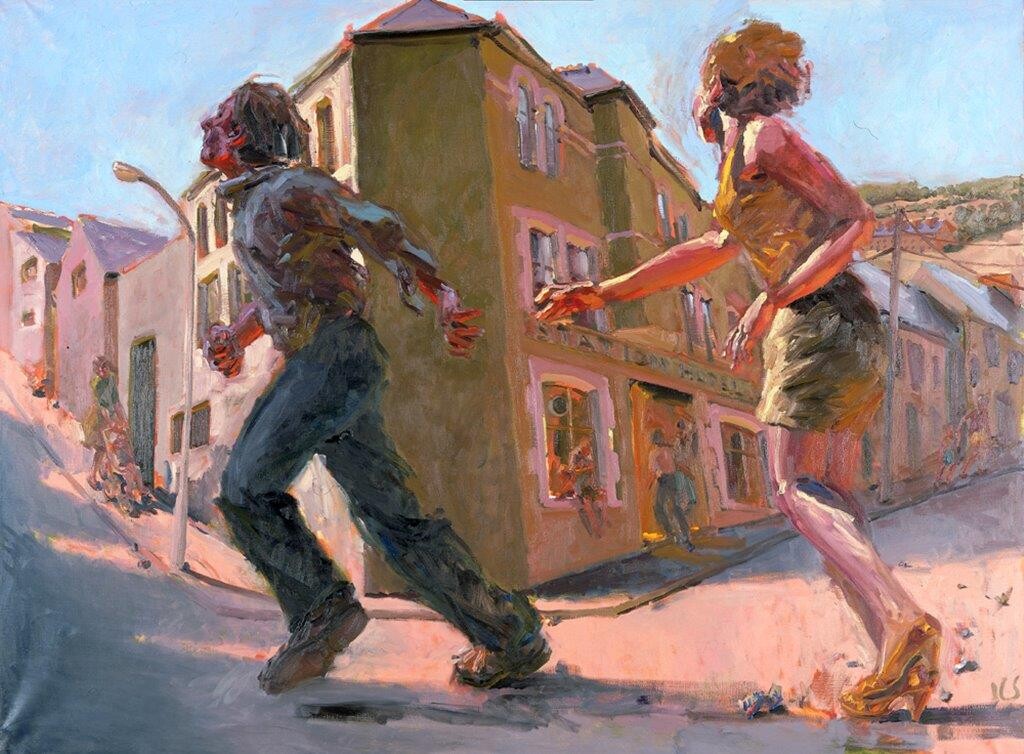

We met on the steps of the museum, "Bet you won’t guess what I’m going to show you" said Simone. She took me to Kevin Sinnott’s painting Running away with the Hairdresser. I laughed. "It’s so free" she said and then, as we sat and looked and looked, we laughed again.

Fluently Simone told me why the painting was significant. "Running away, leaving the past, being someone different or taking control of life. I know how important it is to choose to be the person you want to be. It isn’t easy but this painting tells me it is possible, that’s what I feel about it," she said, "it makes me laugh, it lifts me and I feel a lightness just looking at it. They’re together but not together, he isn’t dragging her away, it’s a choice…or is she chasing him? I don’t really know or care, but this painting speaks to me."

We talked about colour and light; the warm, evening sun casting pinky-purple shadows on skin and down the hill along the Welsh, terraced Street. "I like to think it’s the end of a long day, a summer night. They can’t be apart from each other for a single minute longer, they’re running, running, running away from past lives in that little place where everyone knows them, towards a pinky sunset, so tomor-row will be a fine day, wherever they find themselves. For me it says a sparkling, hopeful, freedom and future."

Three years on from her first art encounter Simone was teaching me about a work I thought I knew, her fresh eye brought insight. Simone saw the work through the lens of her own history, celebrating life in full colour. At first sight Kevin Sinnott’s work seems to bear little similarity with Boswell’s, and yet they are both about emotion, outward expressions of feelings and action. "In all the blackness, for me, red was Hope." Simone said. "Life was worth it and could be good and happy. In the sunlight I see their hope for a better future too, they’re like me. We are the same really." As she talked, her sheer pleasure in the painting was infectious. That day Simone told me she had realised how far she had come in her recovery. She saw both a frivolous moment and a positive future.

Many creative people I work with, pointing to an image, colour or sculpture, have told me "that is it, that is what is going on I’m my head" or "This is why I can’t get out of bed, or read, or do, or think, just consider being dead." "I am unable to move or hear, this is what I feel like." "just look. Look." For Simone it was the J in The A - Z of Emotions. Specifically, "THAT is how I feel. It may be difficult for you to understand or even to accept but it tells me I am not alone." This response may not be as Phoebe Boswell intended when she made the work, it is Simone’s reaction to it. Simone told me later "I know things, I see things and I can talk to people about them, after all, art is for us all, I wish I’d known about it like this before."

Simone felt confident enough to show me her early drawings, she identified threads of her experience and changing style. When we talked of differences between failure and development, Simone tells me she makes art as reference, record and an expression of her changing identity. Making art supports her recovery, in recovery Simone makes art.

A mentoring relationship is built on shared experience; dependent on trust and mutual respect, the mentee needs to feel comfortable enough to be open about the areas they want to work on. Focused, uncritical conversations happen with patience, tolerant, active listening and constructive, feedback for mentoring is to work. If my experience can benefit anyone, I want to pass this on. Establishing a solid mentoring framework, recognising my own limits, I draw on my love for art and personal and profes-sional experience in the arts and other fields, supported by training with Cardiff School of Psychology, the NHS and University of South Wales.

As sensory creatures we are consciously and unconsciously making judgements about what surrounds us all the time. For Simone this is evident as she deploys her enriched art vocabulary, the result of all the thinking, looking, learning and making art. Now she embraces what has happened since her dis-covery of Boswell’s A – Z, added to her experience of her depression and all that went before.

Simone’s powerful emotional response to Sinnott’s work shows how we are at our "most" human and being human brings all sorts of frailties, mental, physical, transient or enduring. How we feel informs our physical response as much as thoughts. We cannot separate the two. Art heals us when we see things which are common to us rather than those differences which tear us apart. In Amgueddfa Cymru, Simone and I came together to see a reflection of human effort and experience in a shared vision of hope. It is not merely a record of events interpreted by the zeitgeist but life affirming art for everyone, us all, everywhere.

*Simone’s name has been changed to protect her identity